Lost in Translation? Afghan Interpreters and Other Locally Employed Civilians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Daily Report Monday, 26 April 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 26 April 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 26 April 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:36 P.M., 26 April 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Prime Minister: Disclosure of BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Information 15 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 7 Public Sector: Procurement 15 Business: Females 7 DEFENCE 16 Department for Business, Armed Forces: Death 16 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Armed Forces: Families 17 Contact Tracing 8 Armed Forces: Suicide 18 Electric Vehicles: Manufacturing Industries 8 Army: Scotland 19 Electricity Interconnectors: Challenger Tanks: Repairs Portsmouth 9 and Maintenance 20 Gratuities 9 David Cameron 20 Hydrogen 9 Military Decorations: Ethnic Groups 20 Hydrogen: Carbon Emissions 10 Ministry of Defence: Greensill 21 Hydrogen: Finance 10 Navy 21 Local Growth Deals: Hartlepool 11 Navy: Radiation Exposure 21 Members: Correspondence 12 Nuclear Weapons 22 OneWeb: Finance 12 Oman: Official Hospitality 22 Re-employment 12 Veterans: Coronavirus 22 Retail Trade: Coronavirus 13 Veterans: Radiation Exposure 23 Transport: Hydrogen 13 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT 24 CABINET OFFICE 14 Coronavirus: Festivals and Civil Service Sports Council: Special Occasions 24 Rosyth 14 Cricket: Coronavirus 24 Government Departments: Procurement 14 Cricket: Government Further Education: Mental Assistance 25 Health Services -

Call Lists for the Chamber Wednesday 21 April 2021

Issued on: 21 April at 12.28pm Call lists for the Chamber Wednesday 21 April 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and a list of Members both physically and virtually present selected to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland 1 2. Oral Questions to the Prime Minister 3 3. Suppression and Prevention of Terrorism: Motion to Approve Order 5 4. Overseas Operations (Service Personnel and Veterans) Bill: Lords Amendments 5 5. Confidentiality in the House’s Standards System; Sanctions in Respect of the Conduct of Members; Sanctions in Respect of the Conduct of Members (IGCS Cases) 7 6. Parliamentary Works Sponsor Body 8 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR NORTHERN IRELAND After prayers Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 1 Patricia Gibson (North What recent assessment his SNP Physical Secretary Lewis Ayrshire and Arran) Department has made of the effect of the Northern Ireland protocol on levels of trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 2, 3 Sir Jeffrey M Supplementary DUP Virtual Secretary Lewis Donaldson (Lagan Valley) 2 Wednesday 21 April 2021 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 4 Alex Davies-Jones Supplementary Lab Physical Secretary Lewis (Pontypridd) 5 Claire Hanna (Belfast Supplementary SDLP Virtual Secretary Lewis South) 6 + 7 Stephen Farry (North What steps the Government Alliance Virtual Secretary Lewis Down) is taking to tackle the causes of the recent disorder in Northern Ireland. -

View Votes and Proceedings PDF File 0.03 MB

No. 144 Tuesday 1 December 2020 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 11.30 am. Prayers 1 Questions to the Chancellor of the Exchequer 2 Apologies: Motion for leave to bring in a Bill (Standing Order No. 23) Ordered, That leave be given to bring in a Bill to make provision for the effect of an apology in certain legal proceedings; That John Howell, John Spellar, Greg Clark, Chris Grayling, Chris Bryant, Kenny MacAskill, Sir Paul Beresford, Sir Roger Gale, Sir Robert Neill, Mrs Heather Wheeler, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson and Rob Butler present the Bill. John Howell accordingly presented the Bill. Bill read the first time; to be read a second time on Friday 5 March 2021, and to be printed (Bill 221). 3 Business of the House (Today) Ordered, That, at today’s sitting, notwithstanding the provisions of Standing Order No. 16 (Proceedings under an Act or on European Union Documents), debate on the Motions in the name of Secretary Matt Hancock relating to the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (All Tiers) (England) Regulations 2020 (SI, 2020, No. 1374) and the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Local Authority Enforcement and Amendment Powers) (England) Regulations 2020 (SI, 2020, No. 1375) may continue until 7.00 pm, at which time the Speaker shall put the questions necessary to bring proceedings on each Motion to a conclusion; and Standing Order No. 41A (Deferred divisions) shall not apply.—(Mr Jacob Rees-Mogg.) 4 Public Health Motion made and Question proposed, That the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (All Tiers) (England) Regulations 2020 (SI, 2020, No. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

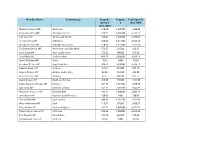

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Strategic Aviation Special Interest

Strategic Aviation Special Interest Group Wednesday 26 February 2020 11.00 am Westminster Room Local Government Association 18 Smith Square Westminster London SW1P 3HZ Guidance notes for members and visitors 18 Smith Square, London SW1P 3HZ Please read these notes for your own safety and that of all visitors, staff and tenants. Welcome! 18 Smith Square is located in the heart of Westminster, and is nearest to the Westminster, Pimlico, Vauxhall and St James’s Park Underground stations, and also Victoria, Vauxhall and Charing Cross railway stations. A map is available on the back page of this agenda. Security All visitors (who do not have an LGA ID badge), are requested to report to the Reception desk where they will be asked to sign in and will be given a visitor’s badge to be worn at all times whilst in the building. 18 Smith Square has a swipe card access system meaning that security passes will be required to access all floors. Most LGA governance structure meetings will take place on the ground floor, 7th floor and 8th floor of 18 Smith Square. Please don’t forget to sign out at reception and return your security pass when you depart. Fire instructions In the event of the fire alarm sounding, vacate the building immediately following the green Fire Exit signs. Go straight to the assembly point in Tufton Street via Dean Trench Street (off Smith Square). DO NOT USE THE LIFTS. DO NOT STOP TO COLLECT PERSONAL BELONGINGS. DO NOT RE-ENTER BUILDING UNTIL AUTHORISED TO DO SO. Open Council Open Council, on the 7th floor of 18 Smith Square, provides informal meeting space and refreshments for local authority members and officers who are in London. -

Defence Committee Formal Minutes Session 2017–19

House of Commons Defence Committee Formal Minutes Session 2017-19 TUESDAY 12 SEPTEMBER2017 Members present: Rt Hon Dr JulianLewis, in the Chair1 Leo Docherty Gavin Robinson Martin Docherty-Hughes Ruth Smeeth Rt Hon Mark Francois Rt Hon John Spellar Graham P Jones Phil Wilson 1. Declaration of interests Members declared their interests, in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 ( see Appendix). 2. Committee working methods The Committee considered this matter. Ordered, That the public be admitted during the examination of witnesses unless the Committee orders otherwise. Resolved, That the Committee examine witnesses in public, except where it otherwise orders. Resolved, That witnesses who submit written evidence to the Committee are authorised to publish it on their own account in accordance with Standing Order No. 135, subject always to the discretion of the Chair or where the Committee orders otherwise. Resolved, That the Committee shall not consider individual cases. Ordered, That John Spellar take the Chair of the Committee, if present, in the absence ofthe Chair. 3. F-35 Procurement The Committee considered this matter. 4. Future programme The Committee considered this matter. 5. Oral evidence: F-35 Procurement Deborah Haynes, Defence Editor, The Times, Alexi Mostrous, Head of Investigations, The Times and Justin Bronk, Research Fellow, RUSI, gave oral evidence. In the absence of the Chair, Mr John Spellar was called to the chair. Justin Bronk, Research Fellow, RUSI, gave further oral evidence. [Adjourned until Wednesday 13 September at 2:30pm. 1Electedbythe House (Standing Order No. 122B ) 12 July 201 7, see Votes and Proceedings 12 July201 7 TUESDAY 7NOVEMBER2017 Members present: Rt Hon Dr Julian Lewis, in the Chair Rt Hon Mr Mark Francois Rt Hon John Spellar Ruth Smeeth Phil Wtl.son I. -

This Is an Email Sent Via the Contact Form on Your Bluetree Website. It Is Not Spam

From: JOHNSTON, Elizabeth B To: Southampton to London Pipeline Project Subject: Southampton to London Pipeline Date: 30 September 2019 11:43:35 Dear Planning Inspector, Leo Docherty MP has asked me to forward to you his representations following the e-mail below from his constituent, Mr. Nick Jarman of Mr. Docherty would be very grateful please for your comments on the representations contained in the e-mail. With best wishes, -- Elizabeth Johnston Senior Parliamentary Assistant Leo Docherty MP Member of Parliament for Aldershot Tel: 020 7219 6298 (direct) Email: [email protected] Website: www.leodocherty.org.uk From: [email protected] <[email protected]> Sent: 30 September 2019 09:05 To: DOCHERTY, Leo <[email protected]> Subject: Bluetree contact form This is an email sent via the Contact form on your Bluetree website. It is not spam. Please do not reply, but instead copy the email address and compose a new message. Name: Nick Jarman Email: Address: Postcode: Telephone: Message: Dear Leo, I am a resident in your constituency in Farnborough. I am writing to you to ask you for your help to reduce the impact of Esso's plans for the Southampton to London Pipeline in your constituency. I hope you are already aware of the project and its associated Development Consent Order. Esso have not done a good job of publicising their plans to those affected by them so there is a chance that you might not have heard about it. The pipeline will pass through a number of sensitive sites in Rushmoor. -

The UAE Lobby: Subverting British Democracy?

The UAE Lobby: Subverting British democracy? Alex Delmar-Morgan David Miller ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHORS Thanks to the Arab Organisation for Human Alex Delmar-Morgan Rights for its financial support for this report. is a freelance journalist in London and has written Thanks also to all those who have shared for a range of national titles information with us about or related to the UAE including The Guardian, lobby. We are indebted to a wide variety of people The Daily Telegraph, and who have shared stories and information with us, The Independent. He is the most of whom must remain nameless. We also former Qatar and Bahrain correspondent for thank Hilary Aked, Izzy Gill, Tom Griffin, Tom Mills. the Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones. On a personal note, thanks to Narzanin Massoumi for her many contributions to this work. David Miller is a director of Public Interest Investigations, of which Spinwatch.org and CONFLICT OF INTEREST Powerbase.info are projects. He STATEMENT is also Professor of Sociology at the University of Bath in No external person had any role in the study, England. From 2013-2016 design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of he was RCUK Global Uncertainties Leadership data, or writing of the report. For the transparency Fellow leading a project on Understanding and policy of Public Interest Investigations and a list of explaining terrorism expertise in practice. grants received see: http://www.spinwatch.org/ index.php/about/funding Recent publications include: • The Quilliam Foundation: How ‘counter- PUBLIC INTEREST extremism’ works, (co-author, Public interest INVESTIGATIONS Investigations, 2018); • Islamophobia in Europe: counter-extremism Public Interest Investigations (PII) is an policies and the counterjihad movement, independent non-profit making organisation. -

London Manchester Number of Employees by Parliamentary

Constituency MP Employees Constituency MP Employees Aberavon Stephen Kinnock 8 Jacobs UK Ltd 1 TWI Ltd 8 KAEFER Limited 18 Aberconwy Robin Millar 4 KDC Contractors Ltd 7 Dounreay Matom Limited 4 Kier Infrastructure and Overseas Ltd Thurso, Caithness 50 Aberdeen North Kirsty Blackman 6 Matom Limited gov.uk/government/organisations/dounreay 9 Bury North Salford SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 1 Mott MacDonald Ltd 2 SLC: Dounreay Site Restoration Ltd Manchester & Eccles Thornton Tomasetti 5 URENCO 485 PBO: Cavendish Dounreay Partnership Ltd Worsley & Aberdeen South Stephen Flynn 2 URENCO Nuclear Stewardship 84 (Cavendish Nuclear, Jacobs, Amentum) Eccles South AECOM 2 Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill Steven Bonnar 71 Lifetime: 1955–1994 Airdrie & Shotts Neil Gray 70 Jacobs UK Ltd 43 Operation: Development of prototype fast Balfour Beatty Kilpatrick 22 Scottish Enterprise 1 breeder reactors Bolton West BRC Reinforcement Ltd 41 SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 27 People: More than 600 ENGIE UK 3 Copeland Trudy Harrison 13,314 Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Wigan Morgan Sindall Infrastructure 4 AECOM 11 Aldershot Leo Docherty 62 ARUP 46 Fluor Corporation 12 Assystem UK Ltd 27 Mirion Technologies (IST) Limited 49 Balfour Beatty Kilpatrick 151 NuScale Power 1 Bechtel 2 Manchester Aldridge-Brownhills Wendy Norton 19 Bureau Veritas UK Ltd 71 The UK Civil Nuclear Industry Central Stainless Metalcraft (Chatteris) Ltd 19 Capita Group 382 Altrincham & Sale West Sir Graham Brady 92 Capula Ltd 10 Mott MacDonald Ltd 92 Cavendish Nuclear Ltd 207 Denton Alyn & Deeside Rt Hon