Meeting Early Malabar Famine Mutiny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of Engg. Trivandrum Mohammed

MALAPPURAM DISTRICT College of engg. Trivandrum Mohammed Shajahan P COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ABDUL AZEEZ C Government Engineering College Thrissur ABDUL AZEEZ KT Federal Institute of Science and Technology Abdul Basith Government Engineering College, Wayanad Abdul Basith K GEC palakkad Abdul Mahroof N MEA Engineering college perinthalmanna ABDUL MAJID K T Gov. Engineering college kozhikode Abdul Muhsin v Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Mes college of engineering Abdul Rishad Malabar Polytechnic college, Kottakkal Abdul Vahid B. S MES COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING,KUTTIPPURAM ABDUL VARIS N FISAT Abhay Krishna SD Tkm college of engineering Abhijit k Nehru college of engineering and reasearch centre Abhijith uk MES CET, KUNNUKARA Abhimanyu ks TKM College Of Engineering, Kollam ABHIRAJ.P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING KOTTARAKKARA ABHIRAM P COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING TRIVANDATUM ABHIRAM P jawaharlal college of engineering and technology Abhishek A S Sreepathy institute of Management and technology Abijith g GEC PALAKKAD ADARSH DAS N Lal Bahadur Shastri College of Engineering, ADARSH DAS.P Eranad Knowledge City Technical Campus Adhil Fuad M.E.S College Of Engineering Adhin Gopuj.A COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY ADHINI ULLAS AK COCHIN COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY VALANCHERI ADHINI ULLAS AK GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE THRISSUR ADITHYA KUMAR M S Al ameen engineering college Adnan mohamed ali College of Engineering Trivandrum Afnan Mohammed A Government engineering college idukki Aghil.P MESCE AHAMED SHAMZAD MK MEA Engineering College Perinthalmanna Ahammed Jouhar E T Mes engineering college kuttipuram Ahammed rasheek Government Engineering College Thrissur AHNAS P P Ncerc Ajay Anand C Govt. -

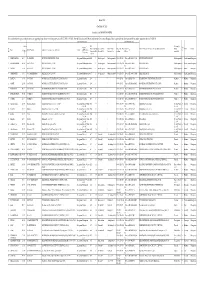

EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl

LIST OF HIGH SCHOOLS IN MALAPPURAM DISTRICT EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT - MALAPPURAM Sl. Std. Std. HS/HSS/VHSS Boys/G Name of Name of School Address with Pincode Block Taluk No. (Fro (To) /HSS & irls/ Panchayat/Muncip m) VHSS/TTI Mixed ality/Corporation GOVERNMENT SCHOOLS 1 Arimbra GVHSS Arimbra - 673638 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Morayur Malappuram Eranad 2 Edavanna GVHSS Edavanna - 676541 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Edavanna Wandoor Nilambur 3 Irumbuzhi GHSS Irumbuzhi - 676513 VIII XII HSS Mixed Anakkayam Malappuram Eranad 4 Kadungapuram GHSS Kadungapuram - 679321 I XII HSS Mixed Puzhakkattiri Mankada Perinthalmanna 5 Karakunnu GHSS Karakunnu - 676123 VIII XII HSS Mixed Thrikkalangode Wandoor Eranad 6 Kondotty GVHSS Melangadi, Kondotty - 676 338. V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Kondotty Kondotty Eranad 7 Kottakkal GRHSS Kottakkal - 676503 V XII HSS Mixed Kottakkal Malappuram Tirur 8 Kottappuram GHSS Andiyoorkunnu - 673637 V XII HSS Mixed Pulikkal Kondotty Eranad 9 Kuzhimanna GHSS Kuzhimanna - 673641 V XII HSS Mixed Kuzhimanna Areacode Eranad 10 Makkarapparamba GVHSS Makkaraparamba - 676507 VIII XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Makkaraparamba Mankada Perinthalmanna 11 Malappuram GBHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Boys Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 12 Malappuram GGHSS Down Hill - 676519 V XII HSS Girls Malappuram ( M ) Malappuram Eranad 13 Manjeri GBHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Mixed Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 14 Manjeri GGHSS Manjeri - 676121 V XII HSS Girls Manjeri ( M ) Areacode Eranad 15 Mankada GVHSS Mankada - 679324 V XII HSS & VHSS Mixed Mankada Mankada -

Rs. 5.00 Crore Funding Per School from KIIFB

Kerala Infrastructure and Technology for Education Infrastructure Projects tendered Centres of Excellence – Rs. 5.00 Crore funding per school from KIIFB No District Constituency School 1 Kozhikode Vadakara JNM GHSS, Kozhikode 2 Kottayam Ettumanoor GHSS Chengalam, Kottayam 3 Alappuzha Chengannur GHSS Mulakuzha, Alappuzha 4 Thiruvananthapuram Aruvikkara GHSS Poovachal, Thiruvananthapuram Betterment of Infrastructure – Rs. 3.00 Crore funding per school from KIIFB Sl No District Constituency Name of School Kasaragode Mogral Puthur GHSS 1 Uduma Adoor GHSS 2 Kanhangad Kanhangad GVHSS 3 Kasaragod Kanhangad Maloth Kasaba GHSS 4 5 Payyannur Mathamangalam CPNGHSS 6 Kalliassery Cherukunnu GHSS Taliparamba Tagore Vidyaniketan GVHSS 7 8 Azhikode Kannadiparamb GHSS 9 Kannur Kannur Munderi GHSS 10 Mattannur Malur GHSS 11 Peravur Chavassery GVHSS 12 Mananthavady Vellamunda GMHSS 13 Mananthavdy Panamaram GHSS 14 Mananthavdy Kartikkulam GHSS 15 Sulthan Bathery Anappara GHSS 16 Sulthan Bathery Moolankavu GHSS 17 Wayanad Sulthan Bathery Vaduvanchal GHS 18 Sulthan Bathery Ambalavayal GHSS 19 Kalpetta Meppadi GHSS Sl No District Constituency Name of School 20 Vadakara Madappalli GVHSS 21 Vadakara Madappally GGHSS 22 Kuttiyadi Kavilumpara GHSS 23 Nadapuram Kallachi GHSS 24 Koyilandi Koyilandi GGHSS 25 Koyilandi Payyoli GVHSS 26 Balussery Poonoor GHSS 27 Balussery Atholi GHSS 28 Balussery Balussery GGHSS 29 Balussery Kokkallur GHSS Elathur Kolathur SGMGHSS 30 Kozhikode 31 Kozhikode North NGO quarters GHSS 32 Kozhikode South Chalappuram GAGHSS 33 Kozhikode South -

In the Context of Malabar Famine

FOOD AND POWER; IN THE CONTEXT OF MALABAR FAMINE *Abdul Rasheed k Research Scholar, Department of History SSUS, Kalady India Throughout the nineteenth century, especially during its latter half, famines were frequent in Colonial India. Under the British colonialism the district of Malabar, a unique socio-political and economic area experienced famine in alternative years. It is presumed that under the British colonial regime Droughts, starvation, famines and pestilences were the order of the day. The present paper contemplates onValluvanad, Eranad and Wayanad Taluks of the colonial district of Malabar. The objective of the Paper is to scrutinize the economic and social causes of famine in Malabar, in general and Eranad, Valluvanad and Wayanad Taluks, in particular and focus on British nexuses with feudal lords, leading to the shortage of food and famine.The present article is organised in three sections; first part defines famine in the Indian context, the second part will discuss scarcity offood and famine, andthe last sectiondiscusses the concept of food and power in the context of Malabar.The objectives of the study concentrate on how the Janmi monopolised the food through differenttenures, customary practices, caste and newly formed colonial regime as tool of exploitation. To checkthe same in the case of the colonial power,harmonised through colonial court, law, taxation, free market policy, rice in price, famine camps, famine commissions and inadequate relief measures led to famine vulnerability. Famines Defined Famines of Malabar -

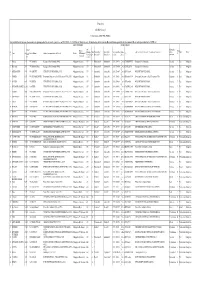

Malappuram Crushers

Details of crusher units in Malappuram District Serial No Crusher Date of inventory Taluk Village Survey Locality Land Owner Firm Operator Status of Crusher code No. U Saidu Malabar Granite U Saidu Working S/O Ahammed Haji Industries S/O Ahammed Haji 1 24 23/07/2011 Eranad Aanakkayam 270/1 Uruniyam House Cheppur Uruniyam House P O Anakkayam Anakkayam P O P O Anakkayam K M Muhammed Al-Ameen Granite K M Muhammed Working S/O Hydru S/O Hydru 2 25 23/07/2011 Eranad Aanakkayam 282pt Puliyilangadi Kalodi House Kalodi House Kallar Mangala Kallar Mangala Randathadi Randathadi C Koyamu Pullancheri Granit C Koyamu Working 3 26 23/07/2011 Eranad Aanakkayam 45/168pt Alungal Pullancheri Industries Pullancheri Mancheri Mancheri C K Abdul Azees Mancheri Bricks C K Abdul Azees Working Anakkayam P O Metals Anakkayam P O 4 27 23/07/2011 Eranad Aanakkayam 281/2 Vettikode Vettekode P R Ashokan P R Ashokan Mancheri Granites Mancheri Granites 5 28 26/07/2011 Eranad Aanakkayam 3/1 Vellarangal Vellarangal Vellarangal P O Manjeri P O Manjeri T.S.Jaleel T.S.Jaleel T.S.Jaleel Working Managing Partner Managing Partner Managing Partner T.S.Yahiye M/S Malabar T.S.Yahiye 266/2,bloc M/S/ Malabar Granites M/S/ Malabar 6 86 10/12/2009 Eranad Cherukavu Ambalakandy k no.4 Granites PO Kannamvettikavu Granites PO Kannamvettikavu 673637 PO Kannamvettikavu 673637 673637 K.Jayaprakash K.Jayaprakash K.Jayaprakash Working Kottarthil House Three star Granites Kottarthil House 7 87 10/12/2009 Eranad Cherukavu 266/2 Ambalakandy Kannamvettikavu(PO) Kannamvettikavu(PO Kannamvettikavu(PO -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Kerala La, 2021

LIST OF DEPLOYED EXPENDITURE OBSERVERS : GE to KERALA LA, 2021 Sl. No. Observer Observer Name Service Year AC Name Email Contact No. Code 1 R-22553 Mr. Sanjoy Paul IRS 2007 1-MANJESHWAR[Kasaragod],2- [email protected] 8986912289 KASARAGOD[Kasaragod] 2 R-20348 Mr. M. Sathishkumar IRS(C&CE) 2010 3-UDMA[Kasaragod],4- [email protected] 8939726010 KANHANGAD[Kasaragod],5- TRIKARIPUR[Kasaragod] 3 R-28500 Dr. Megha Bhargava IRS 2012 6-PAYYANNUR[Kannur],7- [email protected] 9969232929 KALLIASSERI[Kannur],8- TALIPARAMBA[Kannur] 4 R-28524 Mr. Birendra Kumar IRS 2013 9-IRIKKUR[Kannur],10- [email protected] 7588630063 AZHIKODE[Kannur],11- KANNUR[Kannur],12- DHARMADAM[Kannur] 5 R-20865 Mr. Sudhanshu Shekhar IRS 2010 13-THALASSERY[Kannur],14- [email protected] 9477331024 Gautam KUTHUPARAMBA[Kannur],15- MATTANNUR[Kannur],16- PERAVOOR[Kannur] 6 R-21006 Mr. S.Sundar Rajan, IRS IRS 2007 17- [email protected] 8762300070 MANANTHAVADY[Wayanad],18- SULTHANBATHERY[Wayanad], 19-KALPETTA[Wayanad] 7 R-18700 Mr. Mohd. Salik Parwaiz IRS(C&CE) 2009 20-VADAKARA[Kozhikode],21- [email protected] 9407683088 KUTTIADI[Kozhikode],22- NADAPURAM[Kozhikode],23- QUILANDY[Kozhikode] 8 R-21597 Mr. Shree Ram Vishnoi IRS(C&CE) 2011 24-PERAMBRA[Kozhikode],25- [email protected] 9001958758 BALUSSERI[Kozhikode],26- ELATHUR[Kozhikode],27- KOZHIKODE NORTH[Kozhikode] 9 R-22392 Mr. Vibhor Badoni IRS 2009 28-KOZHIKODE [email protected] 9969238168 SOUTH[Kozhikode],29- BEYPORE[Kozhikode],30- KUNNAMANGALAM[Kozhikode], 31-KODUVALLY[Kozhikode],32- THIRUVAMBADY[Kozhikode] 10 R-23005 Mr. Ashish Kumar IRS(C&CE) 2010 34-ERANAD[Malappuram],35- [email protected] 9523813876 NILAMBUR[Malappuram],36- WANDOOR[Malappuram],37- MANJERI[Malappuram] 11 R-20319 Mr. -

The Cultural Shifts After Hadhrami Migration in Malabar

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-3, Issue-9, 2017 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in De-Persianaization of Islam: The Cultural Shifts after Hadhrami Migration in Malabar Anas Edoli Research Scholar, Department of History Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady. Abstract: Hadhrami migration to Malabar in the These reasons were enough to Hadhrami Sayyids to seventeenth century was a land mark issue in the oppose the Kondotty Thangals and their followers. history of Mappila Muslims and they influenced Hadhrami Sayyids started the campaign in early their socio-cultural life. They participated in the years of their migration against the views of religious affairs of Mappila Muslims as well as the Kondotty Thangal. Sheikh Jifri issued many anti colonial struggle against the British. It is Fatwas against them. In later years there emerged a worth mentioning that their role in De- constant dispute between Kondotty and Ponnani Persianaization of Islam in Malabar. In 17 the sect which was commonly known as Ponnani- century there was strong influence of the Kondotty Kondotty Kaitharam. Ponnani sect was of the Sunni Thangal in Malabar who propagated many Shia followers. Therefore Hadhrami Sayyids supported (Persian Islam) ideologies. Hadhrami Sayyids the Ponnani sect. fought against this ideology using their nail and teeth. Sheikh Jifri of Hadhramaut wrote a book 2. Influence of Persian Islam in Malabar against the Kondotty faction and Persian Islam lashing out at their rituals. This paper will analyze Muhammed Sha and his elder son and the activities of Hadhrami Sayyids towards the De- their followers started to propagate the Persian Persianaization of Islam in Malabar. -

MALAPPURAM District, Kerala

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - MALAPPURAM District, Kerala Sl No.of No.of Bearing Annual CPF Reg No. Name of CPF and Contact address Panchayath Block Taluk No. CPSs farmers palms production AREACODE PANJAYATH FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri Sadikali P 1 CPF/MPM/2014-15/065 Areacode Areacode Eranad 8 361 40929 2700474 Kaithayil House, Near I.T.I., Ugrappuram P.O Pin:673639 Mobile:9846612772 NARAGIL FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS 2 CPF/MPM/2015-16/089 SOCIETIES President: Shri A P Muhammed A.P.B Areacode Areacode Eranad 8 702 40003 2055765 House, Areecode, Areecode PO Pin:673639 CHEEKODE GRAMA PANCHAYATH FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri 3 CPF/MPM/2012-13/015 Cheekode Areacode Eranad 19 1292 81524 10198245 Sainudheen K P Puiyamakal House, Cheriayaparambu P.O., Vilayil, Malapuram Pin:673641 Mobile:9846162666 EDAVANNA GRAMA PANCHAYAT FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri K 4 CPF/MPM/2013-14/029 Edavanna Areacode Eranad 10 653 41348 3424275 Muhammed Kallingal (H), Edavanna (PO), Malappuram Pin:676541 Mobile:9895224606 ERANAD FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCING SOCIETY President: Shri Ahammed Kutty Athikkal 5 CPF/MPM/2014-15/079 Edavanna Areacode Eranad 13 854 56689 3673770 House, Kunnummal, Edavanna PO Pin:676541 Mobile:9946274616 KAVANUR GRAMA PANCHAYAT FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETY President: Shri M P 6 CPF/MPM/2013-14/030 Kavannur Areacode Eranad 14 908 59559 6601335 Saidalavi Panampattachalil (H), Erivetty (PO), Kavanur, Malappuram Pin:673639 Mobile:9446215455 -

Form 19 a (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List( GROUP B- PART-I) It

Form 19 A (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List( GROUP B- PART-I) It is certified that the persons whose names are appering in this list are tested as positve as on 07/12/2020 15:13:01 (Date & Time) for covid 19 infection by the Government Hospital/Lab recognized by the Government OR are under quarantine due to COVID 19 ELECTION DETAILS ID CARD DETAILS Gender GP/ Municpality / Name of Ward Sl Municipal / Ward Name of Block Name of Dist Electoral roll Part Name of Address of the present location of hospitalisation/ quarantine Grama Taluk District Name Age Father/ Husband Address for communication with Pincode District GP/Municipal / No No No /M / F Corporation No Divsion & No Divsion & No no Sl no ID card panchayath Corporation /T serial No 1 UMMUHABEEBA 28 F W/o IBRAHIM KINATTINGATHODI HOUSE, 679324 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 7 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo104 Election KL/06/041/333355 KINATTINGATHODI HOUSE Makkaraparamba7 PerinthalmannaMalappuram Id 2 RAMAKRISHNAN 69 M S/o CHANTHU PALLIYALIL HOUSE, 676507 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 3 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo720 Election HFS1508183 PALLIYALIL HOUSE Makkaraparamba3 PerinthalmannaMalappuram Id 3 SAJITHA 35 M W/o RAJEEV PALLIYALIL HOUSE, 676507 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 3 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo723 Election HFS2389799 PALLIYALIL HOUSE Makkaraparamba3 Eranad Malappuram Id 4 PRABHAVATHI 54 F W/o RAMAKRISHNAN PALLIYALIL HOUSE, 676507 Malappuram Makkaraparamba G55 3 Vadakkangara/5 Makkaraparamba/9 Pt.No1 SlNo721 Election KL/06/041/330228 -

Muslim Communities in Kerala to 1798

MUSLIM COMMUNITIES IN KERALA TO 1798 Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy KUNHALI V. Under the Supervision of PROF.(Dr-) M- ZAMEERUDDIN SIDDIQl CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AllGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH 1986 Use/ *... ^.Li*>!i>iQm fiTT, ©F HISTORY. A,«JiS ^ > T5242 27 JUN 2000 Esfc tf THESIS PREFACE This dissertation is an attempt to analyse in detail the history and culture of the various communities that formed the Muslim population of Kerala. Moat of the published works on Muslims of Kerala regarded this group as monolithic* and failed to analyse the different cultural identities that existed among them* These communities played an important role in the cultural development of the region* Published and unpublished works available in Arabic* Arabi-Malayalam and Malayalam formed the source material for this dissertation* The Maulid literature* an equivalent of 'Malfuzat'* was for the first time utilised in this study for social analysis. The major portion of this dissertation is mostly based on extensive field work conducted in different parts of the state* The early coastal settlements* their riverine and interIn extensions were visited fox this study. Necessary information was also collected from different communities on the basis of a prepared questionnaire. Also several festivals and social gatherings were attended and rituals and ceremonies were analysed* for a descriptive accout of the study. ii For the irst time 3uf ism in Kerala was studied tracing lea origin, development* philosophy, rituals and practices and evaluating its role in the spread of the community* Fifteen sub-sections of the community as traced in this study, their relative significance, functional role and social status has been discussed in detail, A realistic appraisal of the condition af Muslim community upto 1798 is earnestly attempted. -

Form 19 a (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List( GROUP B- PART-I) It

Form 19 A (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List( GROUP B- PART-I) It is certified that the persons whose names are appering in this list are tested as positve as on 05/12/2020 16:38:42 (Date & Time) for covid 19 infection by the Government Hospital/Lab recognized by the Government OR are under quarantine due to COVID 19 ELECTION DETAILS ID CARD DETAILS GP/ Municpality / Gender Name of Ward Sl Municipal / Ward Name of Block Name of Dist Electoral roll Part Name of Address of the present location of hospitalisation/ quarantine Grama Taluk District Name Age Father/ Husband Address for communication with Pincode District GP/Municipal / No No No /M / F Corporation No Divsion & No Divsion & No no Sl no ID card panchayath Corporation /T serial No 1 Sumayya 24 F W/o Murshid Ali Karingapara House Punnathala, 676552 Malappuram Athavanad G57 3 Puthanathani/15 Randathani/18 Pt.No2 SlNo744 Election SECID6DE7B57E Karingapara House Punnathala Athavanad 3 Tirur Malappuram Id 2 Mymoonath 55 F W/o Muhammed Kutty Karingapara House Punnathala, 676552 Malappuram Athavanad G57 3 Puthanathani/15 Randathani/18 Pt.No2 SlNo600 Election SECID22627336 Karingapara House Punnathala Athavanad 3 Tirur Malappuram Id 3 fATHIMA KUTTY 58 F W/o ALIKUTTY NEYYATHUR HOUSE KARIPOL, 676552 Malappuram Athavanad G57 7 Athavanad/13 Athavanad/11 Pt.No2 SlNo665 Election KNN1282409 NAYYATHUR HOUSE KARIPOL Athavanad 7 Tirur Malappuram Id 4 NABEESA 52 F W/o MUHAMMEDKUTTY Kotteparambil, Perassannoor, Kutti677591ppuram, 677591, 679571 Malappuram Kuttipuram G61 11 Kolakkad/10 Athavanad/11 Pt.No1