Peri-Urbanization, Illegal Settlements and Environmental Impact In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Gestión Del Agua Potable En La Ciudad De México. Los Retos Hídricos De La Cdmx: Gobernanza Y Sustentabilidad

LORENA TORRES BERNARDINO LA GESTIÓN DEL AGUA POTABLE EN LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO. LOS RETOS HÍDRICOS DE LA CDMX: GOBERNANZA Y SUSTENTABILIDAD 1 COMITÉ EDITORIAL: María de Jesús Alejandro Quiroz Maximiliano García Guzmán Francisco Moyado Estrada Roberto Padilla Domínguez Héctor Zamitiz Gamboa La gestión del agua potable en la Ciudad de México. Los retos hídricos de la CDMX: Gobernanza y sustentabilidad. Primera edición: Febrero de 2017 ISBN: © Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública, A.C. 2 Km. 14.5 Carretera México-Toluca No. 2151 Col. Palo Alto, C.P. 05110 Delegación Cuajimalpa, México, D.F. 50 81 26 57 www.inap.org.mx ISBN: © Instituto de Investigaciones Parlamentarias Asamblea Legislativa del Distrito Federal. VII Legislatura. Dirección Se autoriza la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra, citando la fuente, siempre y cuando sea sin fines de lucro. CONSEJO DIRECTIVO 2014-2017 Carlos Reta Martínez Presidente Carlos F. Almada López Ricardo Uvalle Berrones Ángel Solís Carballo Vicepresidente para Vicepresidente Vicepresidente para los IAPs Asuntos Internacionales de los Estados, 2016-2017 CONSEJEROS José Ángel Gurría Treviño Arturo Núñez Jiménez Julián Olivas Ugalde María Fernanda Casanueva de Diego Jorge Márquez Montes Jorge Tamayo Castroparedes Fernando Pérez Correa Manuel Quijano Torres María del Carmen Pardo López Mauricio Valdés Rodríguez María de Jesús Alejandro Quiroz Eduardo S. Topete Pabello CONSEJO DE HONOR IN MEMORIAM Luis García Cárdenas 3 Ignacio Pichardo Pagaza Gabino Fraga Magaña Adolfo Lugo Verduzco Gustavo Martínez -

The Social Economic and Environmental Impacts of Trade

Journal of Business and Economics, ISSN 2155-7950, USA June 2020, Volume 11, No. 6, pp. 655-659 Doi: 10.15341/jmer(2155-7993)/06.11.2020/003 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2020 http://www.academicstar.us The Environmental Problematic of Xochimilco Lake, Located in Mexico City Ana Luisa González Arévalo (Institute of Economic Research, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico) Abstract: This article presents the geographical location of Lake Xochimilco, some economic and social characteristics of the mayoralty of Xochimilco are mentioned; the inhabitants living in poverty. Subsequently, the serious pollution of this lake and its impact on the health of the inhabitants living near the lake is. Finally, it puts forward some proposals to get started, albeit very slowly reversing this problem Key words: pollution; environment; water; lake; aquifers; geographical location of Lake Xochimilco JEL code: Q53 1. Introduction In this work is geographically located to Lake Xochimilco within the mayoralty of the same name belonging to Mexico City. Subsequently factors are presented such as the total population of this area, a comparison with the total of Mexico City and other more populated mayoralties. Later, this district of Xochimilco is located using some variables such as economic units, occupied personnel, total gross production and fixed assets and some social aspects are mentioned as population and people in poverty. Subsequently I will aboard the serious pollution in the Lake of Xochimilco, which is located 28 kilometers from the Historic Center of Mexico City. 2. Geographical Location of Lake Xochimilco Lake Xochimilco is in the southeast of Mexico City, in the mayoralty of Xochimilco, located 28 kilometers from the city center. -

Mole Sauce Flavor and Livelihood of Atocpan

14 MORALES. Mole Sauce:Layout 1 20/11/09 17:08 Page 65 THESPLENDOROFMEXICO Mole Sauce Flavor and Livelihood Of Atocpan Isabel Morales Quezada* 65 14 MORALES. Mole Sauce:Layout 1 20/11/09 17:08 Page 66 Chocolate tablets. Ancho chili peppers. Pipián paste. fter visiting Atocpan, it is easy to imagine how a little town can be the main supplier of one of Mexico’s most emble- A matic traditional dishes. The town name comes from the Besides being the stuff Nahuatl word atocli, meaning “on fertile earth,” referring to the boun- of legend, what the stories tiful land that allowed the indigenous peoples to grow basic food about its origin reveal is mole crops like corn, lima beans and beans. Today,though, the main local the experimental nature of occupation is not working the land, but making and selling the mole sauce. Each region of the country powder and paste used to make mole sauce. created a different kind. San Pedro Atocpan belongs to Mexico City’s Milpa Alta borough, and its full name reminds us of both its pre-Hispanic and colonial past. Its first inhabitants called it Atocpan, but when the Spaniards arrived, one of their most effective methods for colonizing was spreading the Christian Gos- pel. So, it was the Franciscan friars who added a Christian name to the town, turning it into San Pedro Atocpan. When you arrive, the first thing you see is the large number of businesses selling dif- ferent kinds of mole in both powder and paste form and the ingredients for making it. -

Programa De Mejoramiento De Vivienda

INSTITUTO DE VIVIENDA DEL DISTRITO FEDERAL PROGRAMA DE MEJORAMIENTO DE VIVIENDA BENEFICIARIOS DE AYUDAS DE BENEFICIO SOCIAL EJERCICIO FISCAL 2013 TIPO DE APOYO: MONETARIO FRECUENCIA DE ENTREGA: SEGÚN LÍNEA DE FINANCIAMIENTO APROBADA APELLIDO APELLIDO No. NOMBRE EDAD SEXO UNIDAD TERRITORIAL DELEGACION MONTO PATERNO MATERNO 1 ABOYTES COLIN MARIA ISABEL 45 F FLORES MAGON IZTACALCO $15,320.26 RAFAEL 2 ACEVEDO GARCIA 59 M IXTLAHUACAN IZTAPALAPA $17,639.43 FRANCISCO GRAL. FELIPE GUSTAVO A. 3 ACEVEDO TIRADO YANET 29 F $15,320.26 BERRIOZABAL MADERO SAN MIGUEL 4 ACEVEDO MANCILLA ALICIA 46 F TEOTONGO SECCIONES IZTAPALAPA $20,000.00 LAS TORRES MERCEDES SAN ANTONIO 5 ACEVEDO XOLALPA AVELINA 39 F MILPA ALTA $20,000.00 TECOMITL 6 ACOSTA GODINEZ MARIA JOSEFA 64 F SANTA APOLONIA AZCAPOTZALCO $17,513.76 GUSTAVO A. 7 ACOSTA ACOSTA ANA YAZMIN 32 F CASILDA LA $15,320.26 MADERO CONCHITA-TIERRA 8 ACOSTA ANDRADE IRMA 53 F BLANCA-TORRES TLAHUAC $20,000.00 BODET 9 ACOSTA ANDRADE MARICRUZ 45 F LA LUPITA TLAHUAC $20,000.00 10 AGUILAR JIMENEZ ABRAHAM 54 M SAN ANDRES MIXQUIC TLAHUAC $17,639.43 MARIA GUSTAVO A. 11 AGUILAR HERRERA 46 F SAN PEDRO EL CHICO $15,320.26 ALEJANDRA MADERO GUADALUPE DEL 12 AGUILAR VEGA FRANCISCO 63 M IZTAPALAPA $20,000.00 MORAL 13 AGUILAR JUAREZ ROSA CARMEN 54 F SAN PEDRO XALPA AZCAPOTZALCO $15,320.26 GALO JUSTINO SANTIAGO 14 AGUILAR MORENO 78 M IZTAPALAPA $20,000.00 ANDRES ACAHUALTEPEC 2ª AMP LOMAS DE ALVARO 15 AGUILAR CAMPOS AMADA 67 F $15,320.26 CHAMONTOYA OBREGON GUSTAVO A. 16 AGUILAR CHAVEZ REYES JOSE 56 M UH VILLA ARAGON $15,320.26 MADERO PUEBLO LOS REYES 17 AGUILAR GARCIA DIANA 27 F IZTAPALAPA $20,000.00 CULHUACAN 18 AGUILAR GUERRERO OFELIA 72 F EL SIFON IZTAPALAPA $20,000.00 SAN ANTONIO 19 AGUILAR LOPEZ MARIA ISABEL 31 F MILPA ALTA $20,000.00 TECOMITL 20 AGUILAR MARTINEZ MARTHA 43 F COPILCO EL ALTO COYOACAN $20,000.00 SAN ANTONIO 21 AGUILAR JIMENEZ JANET 35 F MILPA ALTA $20,000.00 TECOMITL ALDO 22 AGUILAR RIVERA 20 M BUENAVISTA. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

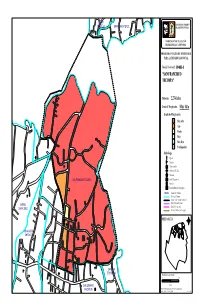

U IA RIV. J S M UAN DE T F C A I L A LE E S D LA BARRERA 5 TE CDA. VICEN BARRIO SUAREZ JEFATURA DE GOBIERNO A S C L O T L A I RE M T F CRUZTITLA O R I L M N BARRIO XOCHITEPETL A A JOSE Ma. N O C PROL. DEL DISTRITO FEDERAL X A C M I S V E CDA. PALMAS C T I E AMINO O POZO 8 C J PR O IV. A SCO S ANCI T VIEJO A SAN FR A E N C O X PA COORDINACIÓN DE PLANEACIÓN DEL DESARROLLO TERRITORIAL PROGRAMA INTEGRADO TERRITORIAL PARA EL DESARROLLO SOCIAL Unidad Territorial: 09-001-1 "SAN FRANCISCO TECOXPA" L C T DA. I SHA M LOM O C E T IO N O T Población: N 2,274 habs. A N A S A Grado de Marginación: Muy Alto Grado de Marginación Muy Alto Z E U G N I O M L O IL Alto D T R O O I Z P AR E S P I O L EL E B OS . J Medio VD BL N O E L Bajo TECOXP O PROL. A V E U N . A D C A Muy Bajo P X A O P C 2a X . PRIV O E . C T TE . .. A A D D C C No Disponible 1 a. PR JO IV SE LO PE PO Z FRAN R CISCO VILLA Simbología TIL LO A Iglesia V 2a. CDA. N . O D E LGO E UEL HIDA END R E MIG LL A. -

3. Sitios Patrimoniales

Programa General de Desarrollo Urbano del Distrito Federal 2001 3. SITIOS PATRIMONIALES NOMBRE DELEGACIÖN NOMBRE DELEGACIÓN ALTAVISTA, SAN ANGEL, CHIMALISTAC, HACIENDA GUADALUPE-CHIMALISTAC Y Álvaro Obregón SANTA BÁRBARA Azcapotzalco 1 BATÁN BARRIO VIEJO, EJE 31 PATRIMONIAL AV. DE LA PAZ, ARENAL 2 AXOTLA Álvaro Obregón 32 SANTA LUCIA Azcapotzalco EJE PATRIMONIAL RUTA DE LA Álvaro Obregón SANTA MARÍA MANINALCO Azcapotzalco 3 AMISTAD 33 4 OBSERVATORIO Álvaro Obregón 34 SANTIAGO AHUIZOTLA Azcapotzalco 5 PUEBLO TETELPAN Álvaro Obregón 35 SANTO TOMÁS Azcapotzalco BARRIO DE MIXCOAC, INSURGENTES SAN BARTOLO AMEYALCO Álvaro Obregón Benito Juárez 6 36 MIXCOAC, SAN JUAN, 7 SANTA FE Álvaro Obregón 37 BARRIO DE XOCO Benito Juárez 8 SANTA LUCÍA Álvaro Obregón 38 LA PIRÁMIDE Benito Juárez 9 SANTA MARÍA NONOALCO Álvaro Obregón 39 NIÑOS HÉROES DE CHAPULTEPEC Benito Juárez 10 SANTA ROSA XOCHIAC Álvaro Obregón 40 SAN LORENZO Benito Juárez 11 TIZAPÁN Álvaro Obregón 41 SAN PEDRO DE LOS PINOS Benito Juárez AZCAPOTZALCO, EJE PATRIMONIAL TACUBA-AZCAPOTZALCO, SAN SIMÓN, Azcapotzalco SAN SIMON TICUMAC Benito Juárez 12 LOS REYES,NEXTENGO, SAN MARCOS 42 ANGEL ZIMBRÓN. 13 BARRIO COLTONGO Azcapotzalco 43 SANTA CRUZ ATOYAC Benito Juárez 14 BARRIO DE SAN ANDRÉS PAPANTLA Azcapotzalco 44 TLACOQUEMECATL Benito Juárez BARRIO DE LOS REYES Y BARRIO DE BARRIO DE SAN SEBASTIAN Azcapotzalco Coyoacán 15 45 LA CANDELARIA 16 BARRIO DE SANTA APOLONIA Azcapotzalco 46 CENTRO CULTURAL UNIVERSITARIO Coyoacán 17 BARRIO HUATLA DE LAS SALINAS Azcapotzalco 47 CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA Coyoacán -

Tours from Mexico City

Free e-guide Mexico City Aztec Explorers PLACES TO EXPLORE INSIDE MEXICO CITY Mexico City – More than 690 years of History In and around the historic center of Mexico City 21 Barrios Mágicos (Magical Neighborhoods) City of Green – National parks, city parks and more City of the Past – Archeological sites in Mexico City City of Culture – City with most museums in the world Apps about Mexico City Books about Mexico City Travelling in and around Mexico City http://www.meetup.com/Internationals-in-Mexico-City-Mexican-Welcome/ http://www.meetup.com/Internationals-in-Mexico-City-Mexican-Welcome/ Mexico City – More than 690 years of History The city now known as Mexico City was founded as Tenochtitlan by the Aztecs in 1325 and a century later became the dominant city-state of the Aztec Triple Alliance, formed in 1430 and composed of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. At its height, Tenochtitlan had enormous temples and palaces, a huge ceremonial center, residences of political, religious, military, and merchants. Its population was estimated at least 100,000 and perhaps as high as 200,000 in 1519 when the Spaniards first saw it. The state religion of the Mexica civilization awaited the fulfillment of an ancient prophecy: that the wandering tribes would find the destined site for a great city whose location would be signaled by an Eagle eating a snake while perched atop a cactus. The Aztecs saw this vision on what was then a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco, a vision that is now immortalized in Mexico's coat of arms and on the Mexican flag. -

México City Travel Guide

T r a v e l G u i d e MINISTRY OF TOURISM INSTITUTE OF TOURIST PROMOTION Mexico City, March 29, 2019 On behalf of Dr. Claudia Sheinbaum, Head of Government of Mexico City, we give you the most cordial welcome to the capital of the country, the capital where everybody is more than welcome, a unique tourist destination in the world, with quality tourism services, a strong bearing on competitiveness and growth, historical places, innovative and inclusive. Mexico City, in addition to World Heritage Sites and ranking second as the city with the greatest number of museums, also offers its visitors a wide range of gastronomic, sporting, nature and recreational options. We hope that this guide becomes your ally to discover and know all the wonders that this great metropolis has for you, a guide for you to enjoy the cultural capital of America and that the warm hospitality of our people encorage you to return soon. Sincerely yours Carlos Mackinlay Secretary of Tourism for Mexico City How to use this Brochure Tap any button in the contents to go to Tap the button to get back to the the selected page. contents page or to the selected map. Contents Map Tap the logo or the image to go to the Tap the button to book your hotel or webpage. tour. Book Here Tap the logos to access the weather forecast, take a virtual tour of archaeological sites via Street View, enjoy videos and photos of México. Follow us in social media and keep up to date with our latest news, promotions and information about the tourist destinations in Mexico. -

Nombre Del Comedor Calle Y Numero Colonia Alcaldía Progreso Nacional Calle 6 #46 Progreso Nacional Gustavo A. Ma

Nombre del comedor Calle y numero Colonia Alcaldía Progreso nacional Calle 6 #46 Progreso nacional Gustavo a. Madero Martha Benito juárez #50 Pueblo san Milpa alta salvador cuauhtenco La cuevita Lago ginebra #6106 Popo Miguel hidalgo Rosita Independencia #24 San álvaro Azcapotzalco Cocina de doña bertha Colinas mz 6 lt 2 Lomas de Álvaro obregón chamontoya Kokito Oriente 185 #101 Villa hermosa Gustavo a. Madero Mujeres en lucha Avenida del rastro s/n Pueblo de san Tlalpan miguel topilejo Comedor de la abuelita 5 lt 4 mz 75 José lópez portillo Iztapalapa Revolucionario Central #51 El olivo Gustavo a. Madero Las gavilanas Nextlalpan mz 786 lt Ampliacion Iztapalapa 10 santiago acahualtepec El paraiso Cerrada tonatiuh mz El paraiso Iztapalapa 19 lt 2 Tepalcates Primavera #76 Tepalcates Iztapalapa Águilas Bahía #93 Ampliación las Álvaro obregón águilas La panza es primero Sur 127 #2415 Gabriel ramos Iztacalco Millán El corazón de Xochimilco Gladiolas #40 Barrio de san Xochimilco Antonio Casa de la luna San Federico mz 619 lt Pedregal de santa Coyoacán 16 Úrsula La esperanza Avenida acueducto Barrio Guadalupe Gustavo a. #659 ticoman Madero Jade del sur Niños héroes #59 Pedregal de san Xochimilco francisco El mirador Mirador mz 29 lt 4 Ampliación Xochimilco Tepepan Tulipanes Tulipanes #4 Ampliación tetitla, Xochimilco santa cruz acalpixca Los 7 ángeles Carretera vieja a Pueblo de santa Xochimilco Xochimilco maría Nativitas tulyehualco #58 El chiquihuite Sor juana Inés de la Del bosque Gustavo a. cruz #11 Madero Tonacayo Avenida 29 de octubre Lomas de la era Álvaro obregón mz 48 lt 2 El errante Viaducto mz 66 lt 2a La estación Tláhuac Mama Yolanda Avenida Veracruz Barrio santa cruz Milpa alta norte #23 San Nicolás Progreso #9 San Nicolás La magdalena totolapan contreras Lomas de Padierna Yobain mz 100 lt 25 Lomas de Padierna Tlalpan Un rinconcito cerca del Quintana roo mz 124 Calma de Gustavo a. -

PROGRAMA Delegacional De Desarrollo Urbano De Milpa Alta

PROGRAMA Delegacional de Desarrollo Urbano de Milpa Alta Al margen un sello con el Escudo Nacional, que dice: Estados Unidos Mexicanos.- Presidencia de la República. PROGRAMA DELEGACIONAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO ÍNDICE 1. FUNDAMENTACIÓN Y MOTIVACIÓN 1.1 ANTECEDENTES 1.1.1 Fundamentación Jurídica 1.1.2 Situación Geográfica y Medio Físico Natural 1.1.3 Antecedentes Históricos 1.1.4 Aspectos Demográficos 1.1.5 Aspectos Socioeconómicos 1.1.6 Actividad Económica 1.2 DIAGNÓSTICO 1.2.1 Relación con la Ciudad 1.2.2 Estructura Urbana 1.2.3 Usos del Suelo 1.2.4 Vialidad y Transporte 1.2.5 Infraestructura 1.2.6 Equipamiento y Servicios 1.2.7 Vivienda 1.2.8 Asentamientos Irregulares 1.2.9 Reserva Territorial 1.2.10 Conservación Patrimonial 1.2.11 Imagen Urbana 1.2.12 Medio Ambiente 1.2.13 Riesgos y Vulnerabilidad 1.2.14 Síntesis de la Problemática 1.3 PRONÓSTICO 1.3.1 Tendencias 1.3.2 Demandas Estimadas de Acuerdo con la Tendencia 1.4 DISPOSICIONES DEL PROGRAMA GENERAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO DEL DISTRITO FEDERAL 1.4.1 Escenario Programático de Población 1.4.2 Demandas estimadas de acuerdo con el Escenario Programático 1.4.3 Áreas de Actuación 1.4.4 Lineamientos Estratégicos Derivados del Programa General 1.5 OTRAS DISPOSICIONES QUE INCIDEN EN LA DELEGACIÓN 1.5.1 Programa Integral de Transporte y Vialidad, 1996-2000 1.5.2 Programa de la Dirección General de Operación y Construcción Hidráulica 1.5.3 Programa de Fomento Económico 1.5.4 Equilibrio Ecológico 1.5.5 Protección Civil 1.5.6 Programa de Desarrollo Rural y Alianza para el Campo 1.6 JUSTIFICACIÓN DE MODIFICACIÓN AL PROGRAMA PARCIAL DE DESARROLLO URBANO 1987. -

Catálogo De Unidades Territoriales 2019

COMISIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Y GEOESTADÍSTICA DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Y GEOESTADÍSTICA DIRECCIÓN DE GEOGRAFÍA Y PROYECTOS ESPECIALES Marco Geográfico de Participación Ciudadana 2019 Catálogo de Unidades Territoriales 2019 Noviembre de 2019 1 de 62 COMISIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Y GEOESTADÍSTICA DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Y GEOESTADÍSTICA DIRECCIÓN DE GEOGRAFÍA Y PROYECTOS ESPECIALES CONCENTRADO DE UNIDADES TERRITORIALES 2019 POR DEMARCACIÓN TERRITORIAL Noviembre de 2019 TOTAL DE NOMBRE DE LA DEMARCACIÓN CLAVE UNIDADES TERRITORIAL TERRITORIALES 02 AZCAPOTZALCO 111 03 COYOACÁN 153 04 CUAJIMALPA DE MORELOS 43 05 GUSTAVO A. MADERO 232 06 IZTACALCO 55 07 IZTAPALAPA 293 08 MAGDALENA CONTRERAS, LA 52 09 MILPA ALTA 12 10 ÁLVARO OBREGÓN 250 11 TLÁHUAC 59 12 TLALPAN 179 13 XOCHIMILCO 79 14 BENITO JUÁREZ 64 15 CUAUHTÉMOC 64 16 MIGUEL HIDALGO 89 17 VENUSTIANO CARRANZA 80 TOTAL 1,815 2 de 62 COMISIÓN DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Y GEOESTADÍSTICA DIRECCIÓN EJECUTIVA DE ORGANIZACIÓN ELECTORAL Y GEOESTADÍSTICA DIRECCIÓN DE GEOGRAFÍA Y PROYECTOS ESPECIALES CONCENTRADO DE UNIDADES TERRITORIALES 2019 POR DISTRITO ELECTORAL LOCAL Noviembre de 2019 NOMBRE DE LA DEMARCACIÓN TOTAL DE UNIDADES DTTO_LOCAL TERRITORIAL TERRITORIALES 2019 01 GUSTAVO A. MADERO 58 02 GUSTAVO A. MADERO 58 03 AZCAPOTZALCO 59 04 GUSTAVO A. MADERO 49 05 AZCAPOTZALCO/MIGUEL HIDALGO 79 06 GUSTAVO A. MADERO 67 07 MILPA ALTA/TLÁHUAC 42 08 TLÁHUAC 29 09 CUAUHTÉMOC 30 10 VENUSTIANO CARRANZA 53 11 VENUSTIANO 37 CARRANZA/IZTACALCO 12 CUAUHTÉMOC -

Centros Culturales En El Distrito Federal

COMISIÓN DE CULTURA CENTROS CULTURALES DISTRITO FEDERAL CENTROS CULTURALES EN EL Centro Cultural Benemérito de las Américas CP 06720, Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal DISTRITO FEDERAL Jardín Centenario 18 Atrio espacio cultural Centro Histórico CP 04000, Coyoacán, Distrito Federal Total 182; Fuente: Sistema de Información Cultural; Orizaba 127 Col. Roma CONACULTA Centro Cultural de la Diversidad Sexual CP 06700, Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal Centro Cultural y Social Hidalguense Colima 267 Casa de Cultura Paco Ignacio Taibo I, II Col. Roma CP 06700, Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal Calz. de Tlalpan 4743 esq. Av. San Fernando Rosas Moreno 110 Col. Tlalpan Centro Col. San Rafael CP 14000, Tlalpan, Distrito Federal Centro de Lectura Condesa CP 06470, Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal Centro de Arte Mexicano Nuevo León 91 Foro Cultural Calpulli-Marina Col. Condesa CP 06100, Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal Cascada 180 Av. Marina Nacional esq. Lago Texcoco Col. Jardines del Pedregal (Dentro de la Unidad Habitacional Marina Nacional 200) CP 01900, Álvaro Obregón, Distrito Federal Casa de Cultura Quinta Colorada Col. Anáhuac CP 11320, Miguel Hidalgo, Distrito Federal Casa de Cultura Ricardo Flores Magón Pedro Antonio de los Santos s/n esq. Av. Constituyentes Col. 1a. Sección del bosque de Chapultepec Centro Cultural Border CP 11850, Miguel Hidalgo, Distrito Federal Calz. de la Virgen esq. Canal Nacional Col. Carmen Serdán Zacatecas 43 CP 04910, Coyoacán, Distrito Federal Casa de Cultura Artes Gráficas Col. Roma Sur CP 06760, Cuauhtémoc, Distrito Federal Casa de Cultura Raúl Anguiano Dr. Vértiz esq. Dr. Arce Jardín de las Artes Gráficas Centro Cultural de España en México Col. Doctores Rey Nezahualcóyotl s/n esq.