1. John Colet Colet's View of Man's Nature John Colet (D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historic Episcopate

THE HISTORIC EPISCOPATE By ROBERT ELLIS THOMPSON, M.A., S.T. D., LL.D. of THE PRESBYTERY of PHILADELPHIA PHILADELPHIA tEfce Wtstminmx pre** 1910 "3^70 Copyright, 1910, by The Trustees of The Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work Published May, 1910 <§;G!.A265282 IN ACCORDANCE WITH ACADEMIC USAGE THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE PRESIDENT, FACULTY AND TRUSTEES OF MUHLENBERG COLLEGE IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF HONORS CONFERRED PREFACE The subject of this book has engaged its author's attention at intervals for nearly half a century. The present time seems propitious for publishing it, in the hope of an irenic rather than a polemic effect. Our Lord seems to be pressing on the minds of his people the duty of reconciliation with each other as brethren, and to be bringing about a harmony of feeling and of action, which is beyond our hopes. He is beating down high pretensions and sectarian prejudices, which have stood in the way of Christian reunion. It is in the belief that the claims made for what is called "the Historic Episcopate" have been, as Dr. Liddon admits, a chief obstacle to Christian unity, that I have undertaken to present the results of a long study of its history, in the hope that this will promote, not dissension, but harmony. If in any place I have spoken in what seems a polemic tone, let this be set down to the stress of discussion, and not to any lack of charity or respect for what was for centuries the church of my fathers, as it still is that of most of my kindred. -

The Stained-Glass Stories of the Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul an Independent Study Project by Aidan Tait ’04

A Hundred-Year Narrative: The Stained-Glass Stories of the Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul an Independent Study Project by Aidan Tait ’04 We are so fortunate to visit daily a place as sacred as this. -Rev. Kelly H. Clark, Ninth Rector of St. Paul’s School The Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul became the focal point of the campus upon its construction and consecration in 1888. Today the Chapel Tower pales only in comparison to the School’s power plant; its hourly bells can be heard from all over the campus. Both figuratively and literally, the building cannot be overlooked in the discussion of School history. And as St. Paul’s prepares to celebrate its 150th anniversary during the 2005-2006 academic year, the Chapel of St. Peter and St. Paul remains of utmost importance in the minds of alumni, faculty, and students alike. Each year the Rector receives new students to the School by welcoming into their Chapel seats; departing seniors use their last day in Chapel to sit in the very seats they occupied as new students. Indeed, the Chapel has a sort of aura about it—of both personal and School history—that makes it meaningful and unforgettable in the minds of those who live here. While taking photographs of the Chapel one Thursday during Spring Term, I met a man from Boston who commuted daily through the area and had decided that afternoon to tour the Big Chapel. He came up to me, his eyes wide with the experience of taking in the building for the first time. -

Historical Survey of Hermeneutics and Homiletics: a Summative Paper

HISTORICAL SURVEY OF HERMENEUTICS AND HOMILETICS: A SUMMATIVE PAPER by Charles E. Handren B.A., California Baptist University, 1995 M.Div., American Baptist Seminary of the West, 1999 A POST-COURSE ASSIGNMENT FOR MN 9101-01 HISTORICAL SURVEY OF HERMENEUTICS AND HOMILETICS Submitted to the faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MINISTRY Concentration in Preaching at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Deerfield, Illinois June, 2013 HISTORICAL SURVEY OF HERMENEUTICS AND HOMILETICS: A SUMMATIVE PAPER In the spring of 2011, I took a Doctor of Ministry course at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School entitled, “Hermeneutics and Homiletics.” One of the required readings was Dennis Johnson’s fine work, Him We Proclaim: Preaching Christ from all the Scriptures. Part one of this book, and particularly chapter four, provides an overview of the history of hermeneutics and homiletics which both aided my understanding of the subject and exposed a significant gap in my knowledge. Specifically, Johnson helped me to see how little I knew about the interpretation and proclamation of the Bible over the last twenty centuries, and how significant a bearing this history has on current issues and debates. Since my Doctor of Ministry concentration is preaching, I thought this gap unacceptable and thus requested an independent reading course which was eventually entitled, “Historical Survey of Hermeneutics and Homiletics.” I set two objectives for the course. First, I aimed to develop a broad and general understanding of the history of the relationship between hermeneutics and homiletics in the Christian church. I have fulfilled this aim by reading a little over five-thousand pages of secondary material, and by building a basic mental framework which now needs to be clarified, strengthened, and built out. -

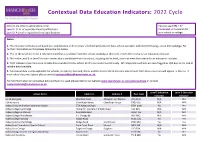

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Church History, Etc. April 2012

Church History, Etc. April 2012 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 Email and Skype: [email protected] Website: http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store); Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- sorry, no phone). Our specialty is used and out-of-print academic books in the areas of theology, church history, biblical studies, and western philosophy. We operate an open shop and coffee house in downtown Eugene. Please stop by if you're ever in the area! When ordering, please reference our book number (shown in brackets at the end of each listing). Prepayment required of individuals. Credit cards: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover; or check/money order in US dollars. Books will be reserved 10 days while awaiting payment. Purchase orders accepted for institutional orders. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. We advise insuring orders of $100.00 or more. Insurance is available at 5% of the order's total, before shipping. Uninsured orders of $100.00 or more are sent at the customer's risk. Returns are accepted on the basis of inaccurate description. Please call before returning an item. Table of Contents Church History 2 English History 104 Historiography 115 Intellectual History 125 Medieval History 149 Church History . __A Brief History for Black Catholics__. Holy Child church. -

1959 the Witness, Vol. 46, No. 36

The ESS NOVEMBER 19, 1959 lop publication. and reuse for required Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of Archives 2020. CANDIDATE FOR HOLY ORDERS Copyright H OWthe SEMINARIANS ministry is oneare ofbeing the preparedmost widely for discussed subjects in the Church today. Part of the training is by taking services in missions or assisting in parishes, like the young man pictured above. Featured this week is the first of two articles on seminary teaching by Earle Fox of General Seminary Thanksgiving Story by Hugh McCandless SERVICES The WITNESS SERVICES In Leading Churches For Christ and His Church In Leading Churches THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH CHRI13ST CHURCH OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINE CAMBRIDGE, MASS. Sunday: Holy Communion 7, 8, 9, 10; EDITORIAL BOARD The Morning Prayer, Holy Communion W. B. SPOFFvORD SR., Managing Editor Revr. Gardiner M. Day, Rector and Sermon, 11; Evensong and ser- KENNETH R. FORBESs; RlOSCOE T. Four; Sunday Services: 8:00, 9:30 and mon, 4. GORDON C. GRAAMa; RBERY HAM~PaSHIRE; 11:15 a.m. Wed, and Holy Days: 8:00 Waekdays: Hloly Communion, 7:30 CHARLES S. M~AnRN; ROBERT F. McGanooa; and 12:10 p.m. (and 10 Wed.); Morning Prayer, GEORGE MACMURRAY; CHARLES F. PEsNuseAs; 8:30; Evensong, 5. W. NORMAN PITENGoER; JOSEPHs 11. TIrUS. CHRIuST CHURCH, DETROrr 976 East Jefferson Avenue THE HEAVENLY REST, NEW YORK 'I'i Rev. William B. Sperry, Rector 5th Avenue at 90th Street 1'l1e11eu. Robert C. W. Ward, Auaf. Rev. John Ellis Large, D.D. CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 8t and 9 a.ms. Holy Communion Sundays: Holy Communion, 7:30 and 9 rTHOMAS V. -

Pico Della Mirandola Descola Gardner Eco Vernant Vidal-Naquet Clément

George Hermonymus Melchior Wolmar Janus Lascaris Guillaume Budé Peter Brook Jean Toomer Mullah Nassr Eddin Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh) Jerome of Prague John Wesley E. J. Gold Colin Wilson Henry Sinclair, 2nd Baron Pent... Olgivanna Lloyd Wright P. L. Travers Maurice Nicoll Katherine Mansfield Robert Fripp John G. Bennett James Moore Girolamo Savonarola Thomas de Hartmann Wolfgang Capito Alfred Richard Orage Damião de Góis Frank Lloyd Wright Oscar Ichazo Olga de Hartmann Alexander Hegius Keith Jarrett Jane Heap Galen mathematics Philip Melanchthon Protestant Scholasticism Jeanne de Salzmann Baptist Union in the Czech Rep... Jacob Milich Nicolaus Taurellus Babylonian astronomy Jan Standonck Philip Mairet Moravian Church Moshé Feldenkrais book Negative theologyChristian mysticism John Huss religion Basil of Caesarea Robert Grosseteste Richard Fitzralph Origen Nick Bostrom Tomáš Štítný ze Štítného Scholastics Thomas Bradwardine Thomas More Unity of the Brethren William Tyndale Moses Booker T. Washington Prakash Ambedkar P. D. Ouspensky Tukaram Niebuhr John Colet Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī Panjabrao Deshmukh Proclian Jan Hus George Gurdjieff Social Reform Movement in Maha... Gilpin Constitution of the United Sta... Klein Keohane Berengar of Tours Liber de causis Gregory of Nyssa Benfield Nye A H Salunkhe Peter Damian Sleigh Chiranjeevi Al-Farabi Origen of Alexandria Hildegard of Bingen Sir Thomas More Zimmerman Kabir Hesychasm Lehrer Robert G. Ingersoll Mearsheimer Ram Mohan Roy Bringsjord Jervis Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III Alain de Lille Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud Honorius of Autun Fränkel Synesius of Cyrene Symonds Theon of Alexandria Religious Society of Friends Boyle Walt Maximus the Confessor Ducasse Rāja yoga Amaury of Bene Syrianus Mahatma Phule Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Qur'an Cappadocian Fathers Feldman Moncure D. -

London Metropolitan Archives Saint

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 SAINT PAUL'S CATHEDRAL: DEAN AND CHAPTER CLC/313 Reference Description Dates CHARTERS Original and copy royal charters and other items, ca1099-1685 (UNCATALOGUED) CLC/313/A/002/MS08762 Charter by King Edward III to St Paul's [1338] June 5 Available only with advance Cathedral, being an inspeximus of grants by In Latin, and notice and at the discretion of the previous monarchs Anglo-Saxon LMA Director Historiated initial letter shows sovereign handing the charter to St Paul. From the initial springs an illuminated bar border with foliage sprays. Not deposited by St Paul's Cathedral. Purchased by Guildhall Library in 1967 1 membrane; fragment of Great Seal on original cord in seal bag Former Reference: MS 08762 CLC/313/A/003/MS11975 Conge d'elire from George III to the Dean and 1764 May 25 Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral for the election of Richard Terrick, bishop of Peterborough, to the see of London Deposited by the London Diocesan Registry 1 sheet Former Reference: MS 11975 CLC/313/A/004/MS25183 Copy of petition from the Dean and Chapter of [1371? - 1435? St Paul's Cathedral to the Crown requesting ] grant of letters patent In French Original reference: A53/25. Undated (late 14th or early 15th century) 1 roll, parchment Former Reference: MS 25183 A53:25 CLC/313/A/005/MS25272 Charter roll, probably compiled during the late [1270 - 1299?] 13th century, recording thirty 11th and 12th In Latin and century royal writs granted to the Cathedral English See Marion Gibbs, "Early Charters of the Cathedral Church of St. -

Literary Deans Transcript

Literary Deans Transcript Date: Wednesday, 21 May 2008 - 12:00AM LITERARY DEANS Professor Tim Connell [PIC1 St Paul's today] Good evening and welcome to Gresham College. My lecture this evening is part of the commemoration of the tercentenary of the topping-out of St Paul's Cathedral.[1] Strictly speaking, work began in 1675 and ended in 1710, though there are those who probably feel that the task is never-ending, as you will see if you go onto the website and look at the range of work which is currently in hand. Those of you who take the Number 4 bus will also be aware of the current fleeting opportunity to admire the East end of the building following the demolition of Lloyd's bank at the top of Cheapside. This Autumn there will be a very special event, with words being projected at night onto the dome. [2] Not, unfortunately, the text of this lecture, which is, of course, available on-line. So why St Paul's? Partly because it dominates London, it is a favourite landmark for Londoners, and an icon for the City. [PIC2 St Paul's at War] It is especially significant for my parents' generation as a symbol of resistance in wartime, and apart from anything else, it is a magnificent structure. But it is not simply a building, or even (as he wished) a monument to its designer Sir Christopher Wren, who was of course a Gresham Professor and who therefore deserved no less. St Paul's has been at the heart of intellectual and spiritual life of London since its foundation 1400 years ago. -

John Colet of Oxford

JOHN COLET OF OXFORD KATHLEEN MACKENZIE City of weather'd cloister and worn court, Grey city of strong towers and clustering spires, Where Art's fresh loveliness would first resort, Where lingering Art kindled her latent fires; * * * * * * Where at each coign of every antique street A memory hath taken root in stone . * * * * * * There Shelley dreamed his white Platonic dreams; There classic Landor throve on Roman thought; There Addison pursued his quiet themes; There smiled Erasmus, and there Colet taught. -Lionel Johnson THE Oxford where Colet taught is not the Oxford of to-day. In Colet's time it was a walled and mediaeval town, more like a fortress than a place of learning. Many of the colleges of to-day were not in existence, but even so it was a city of towers and spires. When Colet walked along the roadway now known as High Street, he saw on his left University College with Merton not far away, both dating from the 13th century. Queen's College, built in the 14th century, stood on his right, Balliol, Exeter and Oriel were known to him. New College, Lincoln and All Souls were already growing old before the first stone of Magdalen, Colet's College, was laid. In 1483, when he went up to Oxford as an undergraduate, Magdalen was still in its infancy. His eyes did not rest on "Maudlin's learned court" nor on the stately tower "whose sweet bells were wont to usher in delightful May". But with each succeeding generation some new beauty was added, until Anthony Wood described it as "the most noble and richest structure in the learned world". -

Theological , Monthly

Concoll~ia . Theological , Monthly AUGUST ~ 1 957 BOOK REVIEW All books reviewed in this periodical may be procured from or through Concordia Pub lishing House, 3558 South Jefferson Avenue, St. Louis 18, Missouri. THE CHRISTIAN FAITH. By David H. C. Read. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1956. 175 pages. Cloth. $1.95. The author, former chaplain of the University of Edinburgh, has recently become George Buttrick's successor as preaching minister of New York's Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church. This is an excellent little "laymen's dogmatics," even though it contains the mild Barthian Calvinism so common in much of modern theology. Its great merit lies in this, that a preacher who sees the need for a functional restatement of Christian doctrine dares to tread the path of systematic theology. Of course not everything in this provocative and helpful adventure in Christian doctrine stands on an equal plane of value. The chapter on the Trinity is outstanding, but the Lutheran will certainly object to such Reformed accents as the assertion that "many who have never heard of [Christ's} name are nevertheless saved by the same grace of God which finds its perfect expression in Him" (p. 167). (There is a slight slip on p. 101; most New Testament interpreters no longer press the de; in connection with JtlOTEU(O as involving a faith "into" the person.) For all its Reformed theology, however, there is reverence here, a power of thought, a facility for writing that comes from a true man of God who knows God's Word, the historic church, people, and himself. -

The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature

The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature Edited by GEORGE WATSON Volume 1 600-1660 CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1974 CONTENTS Editor's preface page xxv List of contributors to volume i xxix Abbreviations XXXI GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. Bibliographies (i) Lists of bibliographical sources column i (2) Journals etc 1 (3) Current lists of new books 3 (4) Current lists of English studies 5 (5) Reference works 5 (6) General library catalogues 7 (7) Catalogues of manuscripts 9 (8) Periods 11 (9) English universities and provinces 15 (10) Religious bodies 19 n. Histories and anthologies (1) General histories 21 (2) General histories of Scottish literature 23 (3) General histories of Irish literature 23 (4) Histories and catalogues of literary genres 25 (5) Anthologies 29 HI. Prosody and prose rhythm (1) General histories and bibliographies 33 (2) Old English .. 33 (3) Middle English 37 (4) Chaucer to Wyatt 37 (5) Modern English 39 (6) Prose rhythm 51 IV. Language A General works 53 (1) Bibliographies 53 (2) Dictionaries 53 (3) Histories of the language, historical grammars etc 55 (4) Special studies 57 B Phonology and morphology (1) Old English 59 (2) Middle English , 75 (3) Modern English 89 CONTENTS C Syntax column in (1) General studies m (2) Old English 117 (3) Middle English 121 (4) Modern English 127 D Vocabulary and word formation 141 (1) General studies 141 (2) Special studies 141 (3) Old English 143 (4) Middle English 153 (5) Modern English 157 (6) Loan-words x 163 E Place and personal names 169 (1) Bibliographies 169 (2) Place-names 169 (3) Personal names 181 THE ANGLO-SAXON PERIOD {TO 1100) I.