The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

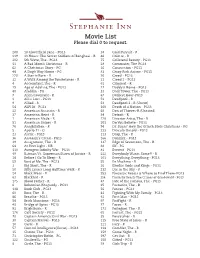

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Released 6Th Februar

Released 6th February 2019 BOOM! STUDIOS OCT181269 BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA OLD MAN JACK TP VOL 03 DEC181361 EMPTY MAN #4 MAIN DEC181362 EMPTY MAN #4 PREORDER HERVAS VAR OCT181277 FEATHERS ORIGINAL GN OCT181240 FIREFLY LEGACY EDITION TP VOL 02 OCT181299 GARFIELD HOMECOMING TP DEC181379 GIANT DAYS #47 DEC181348 WWE #25 NOV188756 WWE #25 FOC GARZA INCV DEC181349 WWE #25 PREORDER XERMANICO DARK HORSE COMICS DEC180358 BPRD DEVIL YOU KNOW #13 OCT180284 BPRD DEVIL YOU KNOW TP VOL 02 PANDEMONIUM OCT180313 ETHER II TP VOL 02 COPPER GOLEMS DEC180403 GIRL IN THE BAY #1 DEC180387 HALO LONE WOLF #2 (OF 4) DEC180404 LAGUARDIA #3 OCT180306 MYSTERY SCIENCE THEATER 3000 #4 CVR A NAUCK OCT180307 MYSTERY SCIENCE THEATER 3000 #4 CVR B VANCE DEC180400 SWORD DAUGHTER #6 CVR A OLIVER DEC180401 SWORD DAUGHTER #6 CVR B CHATER DEC180364 UMBRELLA ACADEMY HOTEL OBLIVION #5 CVR A BA DEC180365 UMBRELLA ACADEMY HOTEL OBLIVION #5 CVR B BA APR180092 WITCHER 3 WILD HUNT BUST CIRI GWENT DC COMICS DEC180529 ADVENTURES OF THE SUPER SONS #7 (OF 12) NOV180532 AQUAMAN SUICIDE SQUAD SINK ATLANTIS TP DEC180510 BATMAN #64 THE PRICE DEC180511 BATMAN #64 VAR ED THE PRICE NOV180547 BLACKEST NIGHT SAGA ESSENTIAL EDITION TP DEC180547 CURSE OF BRIMSTONE #11 JUL180808 DC BOMBSHELLS HARLEY QUINN SEPIA TONE VAR STATUE JUN180604 DC ESSENTIALS SHAZAM & BLACK ADAM AF 2 PACK DEC180549 DEATHSTROKE #40 (ARKHAM) DEC180550 DEATHSTROKE #40 VAR ED (ARKHAM) DEC180555 DREAMING #6 DEC180519 FEMALE FURIES #1 (OF 6) DEC180520 FEMALE FURIES #1 (OF 6) VAR ED DEC180559 GREEN ARROW #49 DEC180560 GREEN -

Subscription Pamplet New 11 01 18

Add More Titles Below: Vault # CONTINUED... [ ] Aphrodite V [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Auntie Agatha's Wayward Bunnies (6) [ ] James Bond [ ] Bitter Root [ ] Lone Ranger [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Blackbird [ ] Mars Attack [ ] Bully Wars [ ] Miss Fury [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Burnouts [ ] Project SuperPowers 625 N. Moore Ave., [ ] Cemetery Beach (of 7) [ ] Rainbow Brite [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Cold Spots (of 5) [ ] Red Sonja Moore OK 73160 [ ] Criminal [ ] Thunderbolt [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Crowded [ ] Turok [ ] Curse Words [ ] Vampirella Dejah Thores [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Cyber Force [ ] Vampirella Reanimator Subscription [ ] Dead Rabbit [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Die Comic Pull Sheet [ ] East of West [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Errand Boys (of 5) [ ] Evolution [ ] ___________________________ We offer subscription discounts for [ ] Exorisiters [ ] Freeze [ ] Adventure Time Season 11 [ ] ___________________________ customers who want to reserve that special [ ] Gideon Falls [ ] Avant-Guards (of 12) comic book series with SUPERHERO [ ] Gunning for Hits [ ] Black Badge [ ] ___________________________ BENEFITS: [ ] Hardcore [ ] Bone Parish [ ] Hit-Girl [ ] Buffy Vampire Slayer [ ] ___________________________ [ ] Ice Cream Man [ ] Empty Man Tier 1: 1-15 Monthly ongoing titles: [ ] Infinite Dark [ ] Firefly [ ] ___________________________ 10% Off Cover Price. [ ] Jook Joint (of 5) [ ] Giant Days [ ] Kick-Ass [ ] Go Go Power Rangers [ ] ___________________________ -

University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

7 0 -m -,1 1 9 WILLIS, Craig Dean, 1935- THE TUDORS AND THEIR TUTORS: A STUDY OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ROYAL EDUCATION IN BRITAIN. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 Education, history University Microfilms. Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Craig Dean W illis 1970 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE TUDORS AND THEIR- TUTORS: A STUDY OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ROYAL EDUCATION IN BRITAIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University SY Craig Dean W illis, B.A., M.A. IHt- -tttt -H-H- The Ohio State U niversity 1969 Adviser t School of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Dr. Robert B. Sutton, my major adviser, I owe a major debt of gratitude for his guidance, encouragement, and scholarly qualifies* I also wish to thank the members of the reading committee for their contribution; and in particular, I want to express appreciation to Dr. Richard J. Frankie and the late Dr. Earl Anderson for their professional and meaningful assistance. It is appropriate to thank the administrative officers at Ohio Wesleyan University for their encouragement and willingness to let me arrange my work around my graduate studies. Persons of particular help were Dr, Allan C. Ingraham, Dr. Elden T. Smith, Dr. Emerson C. Shuck, and Dr. Robert P. Lisensky. My family has been of invaluable assistance to me, and it is to them that I dedicate the study of the education of the Tudor family. My parents, J. Russell and Glenna A. W illis, have helped in many ways, both overt and subtle. -

Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial

Radiant Beings: Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristin Michelle Ferebee Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Thomas S. Davis, Advisor Dr. Jared Gardner Dr. Brian McHale Dr. Rebekah Sheldon 1 Copyrighted by Kristin Michelle Ferebee 2019 2 Abstract The Anthropocene era— a term put forward to differentiate the timespan in which human activity has left a geological mark on the Earth, and which is most often now applied to what J.R. McNeill labels the post-1945 “Great Acceleration”— has seen a proliferation of narratives that center around questions of radioactive, toxic, and other bodily contamination and this contamination’s potential effects. Across literature, memoir, comics, television, and film, these narratives play out the cultural anxieties of a world that is itself increasingly figured as contaminated. In this dissertation, I read examples of these narratives as suggesting that behind these anxieties lies a more central anxiety concerning the sustainability of Western liberal humanism and its foundational human figure. Without celebrating contamination, I argue that the very concept of what it means to be “contaminated” must be rethought, as representations of the contaminated body shape and shaped by a nervous policing of what counts as “human.” To this end, I offer a strategy of posthuman/ist reading that draws on new materialist approaches from the Environmental Humanities, and mobilize this strategy to highlight the ways in which narratives of contamination from Marvel Comics to memoir are already rejecting the problematic ideology of the human and envisioning what might come next. -

Most Creative Mutant Recipes : Action Packed Recipes to Savor Pdf, Epub, Ebook

X-MEN - MOST CREATIVE MUTANT RECIPES : ACTION PACKED RECIPES TO SAVOR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Susan Gray | 92 pages | 05 Mar 2020 | Independently Published | 9798621627935 | English | none X-Men - Most Creative Mutant Recipes : Action Packed Recipes to Savor PDF Book Another thing that complicates the X-Men timelines is the history of the companies that are behind it. The Beast, the ancient demon imprisoned beneath the fortress-city of Elysium for a thousand years, has been loosed on the world. Please, define this superhero's powers properly. United States. She presents one small, achievable change every week—from developing music appreciation to eating brain-boosting foods, practicing mono-tasking, incorporating play, and more. Art by David Baldeon. As Rakeshji claimed that 'KAAL' is like a strong character with a very high level of dexterity for all types of skulduggery , his tall claims fall flat. And Krrish's powers are still not explained, which feel like the over amplification of Rohit's powers. Cole and Hitch will have their work cut out for them to keep the peace, especially when all these ruffians converge at the huge Appaloosa Days festival, where hundreds of innocent souls might get caught in the crossfire. No matter where he turns, the case is waiting for him, haunting his nights and turning his days into a living hell. Ever since the formation of the Five gave the X-Men the ability to resurrect their fallen allies, more and more mutant bodies have been piling up. Chop the script from X-Men series and Spider Man series evenly and boil them in the I am a Legend's script till they turn into Indian flavors. -

Forum Articles the Legacy of 19Th Century Popular Freak Show

Forum Articles The Legacy of 19th Century Popular Freak Show Discourse in the 21st Century X-Men Films Fiona Pettit, PhD Exeter University, United Kingdom Abstract: This essay seeks to tease out the narrative similarities found in nineteenth-century freak show literature and in the X-Men films of the twenty-first century. Both of these forms of popular entertainment emphasize the precarious position of people with extraordinary bodies in their contemporary societies. Keywords: freak, X-Men, disability Introduction In terms of the narrative similarities between the nineteenth-century freak show and the X-Men films, there are two key components that this paper will explore. There exists a striking similarity in how certain freak show performers and mutated characters in the X-Men speak about their condition. Additionally, there is a degree of resonance between how ‘normal’ or non- normative bodies speak of the freak, the mutant, or the “other”. This paper addresses the narrative relationship to demonstrate the legacy of popular nineteenth-century freak show discourse. During the winter season of 1898-1899, the popular Barnum and Bailey Circus, dubbed the “greatest show on earth,” exhibited in London at the Olympia theatre. The show was a huge success and was regularly featured in numerous popular periodicals. In the middle of this season, the freak show performers, who made up a large portion of the circus, held a protest against their designation as “Freaks of Nature”, and instead adopted the title of “Prodigy.” They explained: “In the opinion of many some of us are really the development of a higher type, and are superior persons, inasmuch as some of us are gifted with extraordinary attributes not apparent in ordinary beings” (Man about town, 1899, p. -

X-Men Archives Checklist

X-Men Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Title Card [ ] 02 Angel [ ] 03 Armor [ ] 04 Beast [ ] 05 Bishop [ ] 06 Blink [ ] 07 Cable [ ] 08 Caliban [ ] 09 Callisto [ ] 10 Cannonball [ ] 11 Captain Britain [ ] 12 Chamber [ ] 13 Colossus [ ] 14 Cyclops [ ] 15 Dazzler [ ] 16 Deadpool [ ] 17 Domino [ ] 18 Dust [ ] 19 Elixir [ ] 20 Emma Frost/White Queen [ ] 21 Forge [ ] 22 Gambit [ ] 23 Guardian [ ] 24 Havok [ ] 25 Hellion [ ] 26 Icarus [ ] 27 Iceman [ ] 28 Ink [ ] 29 Jean Grey [ ] 30 Jubilee [ ] 31 Karma [ ] 32 Kuan-Yin Xorn [ ] 33 Lilandra [ ] 34 Longshot [ ] 35 M [ ] 36 Magik [ ] 37 Magma [ ] 38 Marvel Girl [ ] 39 Mercury [ ] 40 Mimic [ ] 41 Mirage [ ] 42 Morph [ ] 43 Multiple Man [ ] 44 Nightcrawler [ ] 45 Northstar [ ] 46 Omega Sentinel [ ] 47 Pixie [ ] 48 Polaris [ ] 49 Prodigy [ ] 50 Professor Xavier [ ] 51 Psylocke [ ] 52 Quicksilver [ ] 53 Rockslide [ ] 54 Rogue [ ] 55 Sage [ ] 56 Shadowcat [ ] 57 Shatterstar [ ] 58 Shola Inkosi [ ] 59 Siryn [ ] 60 Starjammers [ ] 61 Storm [ ] 62 Strong Guy [ ] 63 Sunfire [ ] 64 Sunspot [ ] 65 Surge [ ] 66 Wallflower [ ] 67 Warpath [ ] 68 Wicked [ ] 69 Wind Dancer [ ] 70 Wolfsbane [ ] 71 Wolverine [ ] 72 X-23 Nemesis (1:8 packs) # Card Title [ ] N1 Mr. Sinister by Greg Land [ ] N2 Magneto by Sean Chen and Sandu Florea [ ] N3 Mystique by Mike Mayhew [ ] N4 Sabretooth by Paolo Rivera [ ] N5 Mojo by Frank Cho [ ] N6 Apocalypse by Salvador Larroca [ ] N7 Juggernaut by Sean Chen [ ] N8 Sentinels by Marc Silvestri and Joe Weems [ ] N9 Brotherhood of Evil Mutants by David Finch Cover Gallery -

Staying on the Land: the Search for Cultural and Economic Sustainability in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1996 Staying on the land: The search for cultural and economic sustainability in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland Mick Womersley The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Womersley, Mick, "Staying on the land: The search for cultural and economic sustainability in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland" (1996). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5151. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5151 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University o fMONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission _ X No, I do not grant permission ____ Author's Signature D ate__________________ p L Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. STAYING ON THE LAND: THE SEARCH FOR CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY IN THE HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS OF SCOTLAND by Mick Womersley B.A. -

LGBTQ+ GUIDE to COMIC-CON@HOME 2021 Compiled by Andy Mangels Edited by Ted Abenheim Collage Created by Sean (PXLFORGE) Brennan

LGBTQ+ GUIDE TO COMIC-CON@HOME 2021 Compiled by Andy Mangels Edited by Ted Abenheim Collage created by Sean (PXLFORGE) Brennan Character Key on pages 3 and 4 Images © Respective Publishers, Creators and Artists Prism logo designed by Chip Kidd PRISM COMICS is an all-volunteer, nonprofit 501c3 organization championing LGBTQ+ diversity and inclusion in comics and popular media. Founded in 2003, Prism supports queer and LGBTQ-friendly comics professionals, readers, educators and librarians through its website, social networking, booths and panel presentations at conventions. Prism Comics also presents the annual Prism Awards for excellence in queer comics in collaboration with the Queer Comics Expo and The Cartoon Art Museum. Visit us at prismcomics.org or on Facebook - facebook.com/prismcomics WELCOME We miss conventions! We miss seeing comics fans, creators, pros, panelists, exhibitors, cosplayers and the wonderful Comic-Con staff. You’re all family, and we hope everyone had a safe and productive 2020 and first half of 2021. In the past year and a half we’ve seen queer, BIPOC, AAPI and other marginalized communities come forth with strength, power and pride like we have not seen in a long time. In the face of hate and discrimination we at Prism stand even more strongly for the principles of diversity and equality on which the organization was founded. We stand with the Black, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Indigenous, Latinx, Transgender communities and People of Color - LGBTQ+ and allies - in advocating for inclusion and social justice. Comics, graphic novels and arts are very powerful mediums for marginalized voices to be heard. -

X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E. Shelton Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shelton, Lyndsey E., "X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 146. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/146 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in International Studies. By Lyndsey Erin Shelton Under the mentorship of Dr. Darin H. Van Tassell ABSTRACT It is a widely accepted notion that a child can only be called stupid for so long before they believe it, can only be treated in a particular way for so long before that is the only way that they know. Why is that notion never applied to how we treat, address, and present religion and the religious to children and young adults? In recent years, questions have been continuously brought up about how we portray violence, sexuality, gender, race, and many other issues in popular media directed towards young people, particularly video games.