Thick Relationality: Microtonality and the Technique of Intonation in 21St Century String Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MTO 0.7: Alphonce, Dissonance and Schumann's Reckless Counterpoint

Volume 0, Number 7, March 1994 Copyright © 1994 Society for Music Theory Bo H. Alphonce KEYWORDS: Schumann, piano music, counterpoint, dissonance, rhythmic shift ABSTRACT: Work in progress about linearity in early romantic music. The essay discusses non-traditional dissonance treatment in some contrapuntal passages from Schumann’s Kreisleriana, opus 16, and his Grande Sonate F minor, opus 14, in particular some that involve a wedge-shaped linear motion or a rhythmic shift of one line relative to the harmonic progression. [1] The present paper is the first result of a planned project on linearity and other features of person- and period-style in early romantic music.(1) It is limited to Schumann's piano music from the eighteen-thirties and refers to score excerpts drawn exclusively from opus 14 and 16, the Grande Sonate in F minor and the Kreisleriana—the Finale of the former and the first two pieces of the latter. It deals with dissonance in foreground terms only and without reference to expressive connotations. Also, Eusebius, Florestan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Herr Kapellmeister Kreisler are kept gently off stage. [2] Schumann favours friction dissonances, especially the minor ninth and the major seventh, and he likes them raw: with little preparation and scant resolution. The sforzato clash of C and D in measures 131 and 261 of the Finale of the G minor Sonata, opus 22, offers a brilliant example, a peculiarly compressed dominant arrival just before the return of the main theme in G minor. The minor ninth often occurs exposed at the beginning of a phrase as in the second piece of the Davidsbuendler, opus 6: the opening chord is a V with an appoggiatura 6; as 6 goes to 5, the minor ninth enters together with the fundamental in, respectively, high and low peak registers. -

Cellist and Inter-Disciplinary Artist Anton Lukoszevieze Is One of the Most Diverse Performers of His Generation and Is Notable

Cellist and inter-disciplinary artist Anton Lukoszevieze is one of the most diverse performers of his generation and is notable for his performances of avant-garde, experimental and improvised music. Anton has given many performances at numerous international festivals throughout Europe and the USA (Maerzmusik, Donaueschingen, Wien Modern, GAS, Transart, Ultima) and BBC Radio 3. Deutschlandfunk, Berlin produced a radio portrait of him in September, 2003. Anton has also performed concerti with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra at the 2001 Aldeburgh festival, the Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra at the Tectonics Festival, as well as performances with contemporary vocal ensemble Exaudi and King’s College Choir, Cambridge. He is notable for his use of the curved bow (BACH-Bogen), which he is using to develop new repertoire for the cello. From 2005-7 he was New Music Fellow at King’s College, Cambridge and Kettle’s Yard Gallery. Anton is the subject of seven films by the renowned artist-filmmaker Jayne Parker. In addition he acted and performed in 3 films by the artist Beatrice Gibson. From 2003-14 he was a member of Zeitkratzer and in 2008 made his contemporary dance debut with the Vincent Dance Company in Broken Chords, Dusseldorf. His compositions have been performed by Apartment House, Exaudi, Rhodri Davies, Luce Mense, Mark Knoop, Musica Nova, Tel Aviv and An Assembly. Anton has premiered and commissioned new works for cello by a multitude of contemporary composers, including Christian Wolff, Christopher Fox, Gerhard Staebler, Amnon Wolman, Kunsu Shim, Laurence Crane, Richard Ayres, Phill Niblock, Sven Lyder Karhs, Jennifer Walshe, Claudia Molitor, Rytis Mažulis, Arturas Bumšteinas, Ričardis Kabelis, Juste Janulytė, Richard Emsley, James Saunders, John Lely, Tim Parkinson, Alwynne Pritchard, Peter Eötvös, Egidija Medekšaite, Joseph Kudirka, Benedict Drew, Bryn Harrison, Joseph Kudirka, Mathew Adkins. -

A Clear Apparance

A Clear Apparence 1 People in the UK whose music I like at the moment - (a personal view) by Tim Parkinson I like this quote from Feldman which I found in Michael Nyman's Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond; Anybody who was around in the early fifties with the painters saw that these men had started to explore their own sensibilities, their own plastic language...with that complete independence from other art, that complete inner security to work with what was unknown to them. To me, this characterises the music I'm experiencing by various composers I know working in Britain at the moment. Independence of mind. Independence from schools or academies. And certainly an inner security to be individual, a confidence to pursue one's own interests, follow one's own nose. I donʼt like categories. Iʼm not happy to call this music anything. Any category breaks down under closer scrutiny. Post-Cage? Experimental? Post-experimental? Applies more to some than others. Ultimately I prefer to leave that to someone else. No name seems all-encompassing and satisfying. So Iʼm going to describe the work of six composers in Britain at the moment whose music I like. To me itʼs just that: music that I like. And why I like it is a question for self-analysis, rather than joining the stylistic or aesthetic dots. And only six because itʼs impossible to be comprehensive. How can I be? Thereʼs so much good music out there, and of course there are always things I donʼt know. So this is a personal view. -

8.1.4 Intervals in the Equal Temperament The

8.1 Tonal systems 8-13 8.1.4 Intervals in the equal temperament The interval (inter vallum = space in between) is the distance of two notes; expressed numerically by the relation (ratio) of the frequencies of the corresponding tones. The names of the intervals are derived from the place numbers within the scale – for the C-major-scale, this implies: C = prime, D = second, E = third, F = fourth, G = fifth, A = sixth, B = seventh, C' = octave. Between the 3rd and 4th notes, and between the 7th and 8th notes, we find a half- step, all other notes are a whole-step apart each. In the equal-temperament tuning, a whole- step consists of two equal-size half-step (HS). All intervals can be represented by multiples of a HS: Distance between notes (intervals) in the diatonic scale, represented by half-steps: C-C = 0, C-D = 2, C-E = 4, C-F = 5, C-G = 7, C-A = 9, C-B = 11, C-C' = 12. Intervals are not just definable as HS-multiples in their relation to the root note C of the C- scale, but also between all notes: e.g. D-E = 2 HS, G-H = 4 HS, F-A = 4 HS. By the subdivision of the whole-step into two half-steps, new notes are obtained; they are designated by the chromatic sign relative to their neighbors: C# = C-augmented-by-one-HS, and (in the equal-temperament tuning) identical to the Db = D-diminished-by-one-HS. Corresponding: D# = Eb, F# = Gb, G# = Ab, A# = Bb. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Saunders, James Developing a modular approach to music Original Citation Saunders, James (2003) Developing a modular approach to music. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/5942/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ CONTENTS Table Figures of ............................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................vi Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... -

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder

Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2010 ABSTRACT Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder In this paper, I describe my recent work, which is primarily focused around a dynamic tuning system, and the construction of new electro-acoustic instruments using this system. I provide an overview of my aesthetic and theoretical influences, in order to give some idea of the path that led me to my current project. I then explain the tuning system itself, which is a type of dynamically tuned just intonation, realized through electronics. The third section of this paper gives details on the design and construction of the instruments I have invented for my own compositional purposes. The final section of this paper gives an analysis of the first large-scale piece to be written for my instruments using my tuning system, Concerning the Nature of Things. Exploration of an Adaptable Just Intonation System Jeff Snyder I. Why Adaptable Just Intonation on Invented Instruments? 1.1 - Influences 1.1.1 - Inspiration from Medieval and Renaissance music 1.1.2 - Inspiration from Harry Partch 1.1.3 - Inspiration from American country music 1.2 - Tuning systems 1.2.1 - Why just? 1.2.1.1 – Non-prescriptive pitch systems 1.2.1.2 – Just pitch systems 1.2.1.3 – Tempered pitch systems 1.2.1.4 – Rationale for choice of Just tunings 1.2.1.4.1 – Consideration of non-prescriptive -

Programme Notes

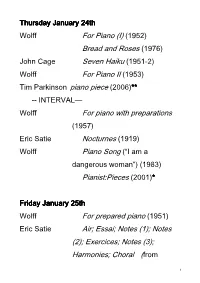

Thursday January 24th Wolff For Piano (I) (1952) Bread and Roses (1976) John Cage Seven Haiku (1951-2) Wolff For Piano II (1953) Tim Parkinson piano piece (2006)****** -- INTERVAL— Wolff For piano with preparations (1957) Eric Satie Nocturnes (1919) Wolff Piano Song (“I am a dangerous woman”) (1983) Pianist:Pieces (2001) *** Friday January 25th Wolff For prepared piano (1951) Eric Satie Air; Essai; Notes (1); Notes (2); Exercices; Notes (3); Harmonies; Choral (from 1 'Carnet d'esquisses et do croquis', 1900-13 ) Wolff A Piano Piece (2006) *** Charles Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) Steve Chase Piano Dances (2007-8) ****** Wolff Accompaniments (1972) --INTERVAL— Wolff Eight Days a Week Variation (1990) Cornelius Cardew Father Murphy (1973) Howard Skempton Whispers (2000) Wolff Preludes 1-11 (1980-1) Saturday January 26th Christopher Fox at the edge of time (2007) *** Wolff Studies (1974-6) Michael Parsons Oblique Pieces 8 and 9 (2007) ****** 2 Wolff Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida (1979) --INTERVAL-- Wolff Suite (I) (1954) For pianist (1959) Webern Variations (1936) Wolff Touch (2002) *** (** denotes world premiere; *** denotes UK premiere) for pianist: the piano music of Christian Wolff Given the importance within Christian Wolff’s compositional aesthetic of music which involves interaction between players, it is perhaps surprising that there is a significant body of works for solo instrument. In particular the piano proves to be central 3 to Wolff’s output, from the early 1950s to the present day. These concerts include no fewer than sixteen piano solos; I have chosen not to include a number of other works for indeterminate instrumentation which are well suited to the piano (the Tilbury pieces for example) as well as two recent anthologies of short pieces, A Keyboard Miscellany and Incidental Music , and also Long Piano (Peace March 11) of which I gave the European premiere in 2007. -

Shadings in the Chromatic Field: Intonations After Morton Feldman

Shadings in the Chromatic Field: Intonations after Morton Feldman Marc Sabat ... this could be an element of the aural plane, where I'm trying to balance, a kind of coexistence between the chromatic field and those notes selected from the chromatic field that are not in the chromatic series.1 Harmony, or how pitched sounds combine, implies microtonality, enharmonic variations of tuning. Historically, these came to be reflected in written music by having various ways of spelling pitches. A harmonic series over E leads to the notes B and G#, forming a just major triad. Writing Ab instead of G# implies a different structure, but in what way? How may such differences of notation be realized as differences of sound? The notion of enharmonic "equivalence," which smooths away such shadings, belongs to a 20th century atonal model: twelve-tone equal temperament. This system rasters the frequency glissando by constructing equal steps in the irrational proportion of vibration 1:12√2. Twelve successive steps divide an octave, at which interval the "pitch- classes" repeat their names. Their vertical combinations have been exhaustively demonstrated, most notably in Tom Johnson's Chord Catalogue. However, the actual sounding of pitches, tempered or not, always reveals a microtonally articulated sound continuum. Hearing out the complex tonal relations within it suggests a new exploration of harmony: composing intonations in writing, playing and hearing music. Morton Feldman recognized that this opening for composition is fundamentally a question of rethinking the notational image. In works composed for the most part between 1977 and 1985, inspired by his collaboration with violinist Paul Zukofsky, Feldman chose to distinguish between enharmonically spelled pitches. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9401223 Harmonic tonality in the theories of Jerome-Joseph Momigny Caldwell, Glenn Gerald, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 UMI 300 N. -

Philip Thomas - Piano

Something New, Something Old, Something Else (2) Philip Thomas - piano Laurence Crane Chorale for Howard Skempton (1997) Howard Skempton senza licensa (1974) Laurence Crane Derridas (1985-6) 1. Jacques Derrida Goes To A Nightclub 2. Jacques Derrida Goes To A Massage Parlour 3. Jacques Derrida Goes To The Supermarket 4. Jacques Derrida Goes To The Beach Laurence Crane Birthday Piece for Michael Finnissy (1996) Michael Finnissy First Political Agenda (1989-2006) WORLD PREMIERE (complete) 1. Wrong place. Wrong time. 2. Is there any future for new music? 3. You know what kind of sense Mrs. Thatcher made. --- INTERVAL --- John White Piano Sonatas 154 (‘Carbon Footprints in the Snow’), 166 , 162 (‘MayDay’) (2007-8) Howard Skempton Second Gentle Melody (1975) Bryn Harrison I-V (2003) Laurence Crane Piano Piece No.23 'Ethiopian Distance Runners' (2009) WORLD PREMIERE This concert is the second of two given as part of the five40five series, grouped together under the title Something New, Something Old, Something Else . The primary intention is that a major new work is commissioned from a composer whose music I find to be radical, original and ultimately inspiring. Then, an older work by the same composer is chosen to go alongside the new work and the programme is completed with works by other composers, from any musical period or style, that might demonstrate connections, traces, influences, or even disparities. These works have been selected after discussions between the composers and myself. The two composers who have written new works for this project – Markus Trunk for the concert in May, and Laurence Crane for tonight’s concert - are composers whose music I respond to at a very intuitive level. -

Developing a Modular Approach to Music

University of Huddersfield Repository Saunders, James Developing a modular approach to music Original Citation Saunders, James (2003) Developing a modular approach to music. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/5942/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Developing a modular approach to music James Saunders A portfolio of compositions and commentary submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2003 CONTENTS Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................... -

Intervals an Interval Is the Distance Between One Note and Another

Intervals An interval is the distance between one note and another. It is always measured from the lower note. Working out intervals can be very similar to working out scale degrees. The smallest interval in western notation is a semitone (or half-tone) and there is no real limit (other than the range of human hearing – 20Hz to 20kHz) for the largest interval. Major and minor intervals The distance from C to D is a whole tone. D is the second degree of the scale of C major, so it is known as a ‘ major second ’. The distance from C to E is a ‘major third ’. However: the distance from C to Eb is a ‘ minor third ’, as the note E is lowered by one semitone. 1 to b2 = minor second 1 to 2 = major second 1 to b3 = minor third 1 to 3 = major third 1 to b6 = minor sixth 1 to 6 = major sixth 1 to b7 = minor seventh 1 to 7 = major seventh Perfect intervals You will have noticed that the fourth, fifth and octave are missing from the table above. These intervals are considered ‘perfect ’, and different rules apply to them. For example, instead of ‘major’ the interval between note 1 and note four is known as a ‘perfect’ interval. There are no minor intervals when using the ‘perfect’ intervals – a perfect interval that has been lowered by a semitone is known as ‘diminished’. 1 to b4 = diminished fourth 1 to 4 = perfect fourth 1 to b5 = diminished fifth (the ‘devil’s interval’) 1 to 5 = perfect fifth 1 to b8 = diminished octave 1 to 8 = perfect octave N.B.