Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year-Olds, Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consuming-Kids-Transcript.Pdf

1 MEDIA EDUCATION F O U N D A T I O N 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org Consuming Kids The Commercialization of Childhood Transcript INTRODUCTION The consumer embryo begins to develop during the first year of existence. Children begin their consumer journey in infancy. And they certainly deserve consideration as consumers at that time. – James U. McNeal | Pioneering Youth Marketer [TITLE SCREEN] Consuming Kids: The Commercialization of Childhood NARRATOR: Not since the end of World War II, at the height of the baby boom, have there been so many kids in our midst. There are now more than 52 million kids under 12 in all in the United States – the biggest burst in the U.S. youth population in half a century. And for American business, these kids have come to represent the ultimate prize: an unprecedented, powerful and elusive new demographic to be cut up and captured at all costs. There is no doubt that marketers have their sights on kids because of their increasing buying power – the amount of money they now spend on everything from clothes to music to electronics, totaling some 40 billion dollars every year. But perhaps the bigger reason for marketers’ interest in kids may be the amount of adult spending that American kids under 12 now directly influence – an astronomical 700 billion dollars a year, roughly the equivalent of the combined economies of the world’s 115 poorest countries. DAVID WALSH: One economic impact of children is the money that they themselves spend – the money that they get from their parents or grandparents, the money that they get as allowance; when they get older, the money that they earn themselves. -

Intelligence Squared U.S. Debates

Intelligence Squared U.S. - 1 - Press Contacts: October 12, 2011 Andy Silva | 718.522.7171 [email protected] Matt Hanks | 718.522.7171 [email protected] Mark Satlof | 718.522.717 [email protected] Intelligence Squared U.S. Too many kids go to college For the Motion: Charles Murray, Peter Thiel Against the Motion: Henry Bienen, Vivek Wadhwa Moderator: John Donvan AUDIENCE RESULTS Before the debate: After the debate: 39% FOR 47% FOR 40% AGAINST 46% AGAINST 21% UNDECIDED 7% UNDECIDED Start Time: (19:50:51) John Donvan: Intelligence Squared exists because of the efforts of Robert Rosenkranz, who brought it to the United States and has made this thing grow and spread. And it's been a terrific effort. And tonight it's a feather in his cap and our cap. So ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Robert Rosenkranz. [applause] Robert Rosenkranz: Thank you, and welcome. We're so pleased to be here in Chicago and proud to be a partner with the first Chicago Ideas Week. My role in these proceedings is to frame the debate, to outline the reasons we felt it was worth having. Tonight's motion is so counterintuitive one might wonder why we chose it as a topic. After all, there seems to be ample statistical support for the value of a college education. College graduates earn about $20,000 a year more than high school graduates, nearly half a million dollars over their lifetimes. Some 9.7 percent of high school graduates are currently unemployed compared with 4.2 percent of college graduates. 19:51:58 Prepared by National Capitol Contracting 200 N. -

BUCKEYE COUNTRY SUPERFEST Presented by Budweiser KENNY

BUCKEYE COUNTRY SUPERFEST presented by Budweiser Saturday, June 20, 2020 at Ohio Stadium KENNY CHESNEY FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE KANE BROWN * BRETT YOUNG * GABBY BARRETT WITH TYLER RICH September 24, 2019 (Columbus, Ohio) – Just announced, “The King of the Road”, Kenny Chesney will headline Buckeye Country Superfest 2020 presented by Budweiser. Chesney will be joined by Multi-platinum duo Florida Georgia Line, RIAA Gold-Certified Kane Brown, ASCAP’s 2018 Country Songwriter-Artist of the Year Brett Young, Radio Disney’s “Next Big Thing” Gabby Barrett, plus 2018 CMT Listen Up Artist Tyler Rich at iconic Ohio Stadium in Columbus, Ohio. “To say we are stoked to share the stage with the king of island vibes himself is an understatement,” shares FGL’s Brian Kelley. “We’ve been huge fans of Kenny for a long time and this is definitely going to be a party!” “We’ve been lucky enough to play several stadiums nationwide, but this will be our first time doing it in Ohio,” adds FGL’s Tyler Hubbard. “Each one has its own iconic magic and we can’t wait to see the Buckeye fans out in full force!” When asked about coming to Buckeye Country Superfest, Brett Young said “Performing in a football stadium in the summertime for thousands of hyped up country music fans will always be pretty surreal and special. Ohio, my calendar is already circled for this one!” 2020 will mark the fifth year Ohio Stadium opens its gates for Buckeye Country Superfest. An enthusiastic crowd of 55,402 country music fans two-stepped and sang along at Buckeye Country Superfest 2019, setting the single day attendance record for the festival. -

A Dissertation Entitled Descriptive Cases of Gifted Indian American

A Dissertation entitled Descriptive Cases of Gifted Indian American Students and their Families By Karen J. Micko Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Curriculum and Instruction ______________________________________________________ Dr. Leigh Chiarelott, Committee Co-Chair ______________________________________________________ Dr. Jane Piirto, Committee Co-Chair ______________________________________________________ Dr. Marcella Kehus, Committee Member ______________________________________________________ Dr. Lynne Hamer, Committee Member ______________________________________________________ Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2015 Copyright 2015, Karen Janish Micko This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. ii An Abstract of Descriptive Cases of Gifted Indian American Students and their Families by Karen J. Micko Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Curriculum and Instruction The University of Toledo December 2015 There is a sparsity of research focusing on the experiences of Asian-Indian American students. This study describes how gifted Indian American students and their families perceived factors contributing to the students’ academic success. Specifically, this study used a qualitative case study design to describe -

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints/Mormon Children’S Music: Its History, Transmission, and Place in Children’S Cognitive Development

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS/MORMON CHILDREN’S MUSIC: ITS HISTORY, TRANSMISSION, AND PLACE IN CHILDREN’S COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Colleen Jillian Karnas-Haines, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005. Dissertation Directed by: Professor Robert C. Provine Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology School of Music The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a children’s auxiliary program for ages three to eleven that meets weekly before or after their Sunday worship service. This auxiliary, called Primary, devotes much of its time to singing. Music is not a childish diversion, but an essential activity in the children’s religious education. This study examines the history of the songbooks published for Primary use, revealing the many religious and cultural factors that influence the compilations. The study then looks at the modern methods of transmission as the author observes the music education aspects of Primary. Lastly, the study investigates the children’s use of and beliefs about Primary music through the lens of cognitive development. The study reveals that Primary music is an ever-evolving reflection of the theology, cultural trends, and practical needs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Unaware of such implications, the children use Primary music to express their religious musicality at cognitive developmentally appropriate levels. THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS/MORMON CHILDREN’S MUSIC: ITS HISTORY, TRANSMISSION, AND PLACE IN CHILDREN’S COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT By Colleen Jillian Karnas-Haines Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor Robert C. -

Jack and Diane (John Mellencamp)

Jack and Diane (John Mellencamp) Little ditty about Jack and Diane "Well then, there Diane, we ought to run off Two American kids growin' up in the to the city" heartland Diane says, "Baby, you ain't missin' Jack, he's gonna be a football star nothing" Diane's debutante backseat of Jacky's car But Jacky say Suckin' on a chili dog outside the Tastee Oh yeah, life goes on Freez Long after the thrill of livin' is gone Diane's sittin' on Jacky's lap Oh yeah say life goes on He's got his hand between her knees Long after the thrill of livin' is gone Jacky say, "Hey Diane, lets run off behind a shady tree Dribble off those Bobby Brooks slacks Gonna let it rock Let me do what I please" Let it roll And Jacky say Let the Bible belt come and save my soul Hold on to sixteen as long as you can Oh yeah, life goes on Changes come around real soon Long after the thrill of livin' is gone Make us women and men Oh yeah say life goes on Long after the thrill of livin' is gone Oh yeah, life goes on They walk on Long after the thrill of livin' is gone Oh yeah say life goes on Jacky sits back, collects his thoughts for the Long after the thrill of livin' is gone moment Scratches his head and does his best James Little ditty about Jack and Diane Dean Two American kids doing the best they can 111 "Jack & Diane" is a 1982 hit rock song written and performed by American singer-songwriter John Mellencamp, then performing as "John Cougar." It appears on Mellencamp's album American Fool. -

How to Protect Kids from Child Molesters 1

How to Protect Kids from Child Molesters 1 How to Protect Kids from Child Molesters 2 Back of title page Copyright © 2007 by Lauren Ayers All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Appledorn Publishers, Guilderland, New York. Dear Abby’s column reprinted with permission pending of Dear Abby, Creators and Los Angeles Times Syndicates. Excerpt from Conversations with a Pedophile by John Smith permissions pending Library of Congress Catalogue number 0000000000 ISBN: 0000000000 Cover design by John Smith Cover photograph by John Smith Manufactured in the United States of America How to Protect Kids from Child Molesters 3 Let my little light shine How to Protect Kids from Child Molesters 4 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part 1: The Problem Chapter One: Empty Streets The way kids live – Kids as crime targets – Parental confusion Chapter Two: Crisis of Confidence: American Parents at a Loss How parents lost their sense of control over their children’s safety – Blurring the line to hide the crime – Parents under pressure – Have kids have lost faith in their parents’ ability to protect them? – Kids don’t tell their parents about sexual crimes – What determines whether children disclose? – False accusations – Parental ambivalence Chapter Three: American Institutions Under Attack Public and private schools – Religious institutions – Recreational organizations Part 2: The Challenge to Child Protection Chapter Four: The Sexual Con Man Sexual predators as con men -

Kenny Chesney Launches No Shoes Radio on Siriusxm Exclusively

NEWS RELEASE Kenny Chesney Launches No Shoes Radio on SiriusXM Exclusively 3/29/2016 - No Shoes Radio, curated by Kenny, to launch on SiriusXM April 12 - Exclusive, private concert for SiriusXM subscribers at Asbury Park NJ's Stone Pony to air live on Chesney's No Shoes Radio SiriusXM channel NEW YORK, March 29, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM announced today that Kenny Chesney, country music superstar and the man The Wall Street Journal called "The King of the Road," will bring his No Shoes Radio channel exclusively to SiriusXM. No Shoes Radio, Kenny Chesney's exclusive SiriusXM channel, curated by Chesney himself, will feature music from Chesney, from his favorite artists across multiple styles of music, rare live performances and special coverage of backstage happenings at Chesney's concerts. To celebrate the SiriusXM launch of No Shoes Radio, Kenny Chesney will perform a special, private concert for SiriusXM at the legendary Stone Pony in Asbury Park, NJ on May 12. The concert will air live and exclusively on Chesney's No Shoes Radio. "We've spent eight years building No Shoes Radio," says the 8-time Academy of Country Music and Country Music Association Entertainer of the Year. "It's always been a place where I could share songs I love, musicians I find, things on my computer nobody's ever heard – and blur the lines between my records and everything from reggae to rock to bluegrass. To partner with SiriusXM as part of their Artist Driven platform of stations means No Shoes Radio will be able to reach even more people who love songs and music the same way I do. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Garth Songs: Ainʼt Going Down Rodeo the Dance Papa Loves Mama the River Thunder Rolls That Summer Much Too Young Baton Rouge

Garth songs: Ainʼt going down Rodeo The dance Papa loves mama The river Thunder rolls That summer Much too young Baton Rouge Tim McGraw Live like you were dying Meanwhile back at mamas Donʼt take the girl The highway donʼt care Sleep on it Diamond rings and old barstools Red rag top Shot gun rider Green grass grows I like it I love it Something like that Miranda Lambert: Baggage claim Tin man Vice Mamas broken heart Pink sunglasses Gunpowder and lead Kerosene Little red wagon House that built me Famous in a small town Hell on heels Alan Jackson: Chattahootchie Here in the real world 5 oʼclock somewhere Remember when Mercury blues Donʼt rock the jukebox Chasing that neon rainbow Summertime blues Must be love Whoʼs cheating who Vince Gill: Liza Jane Cowgirls do Dont let our love start slipping away I still believe in you Trying to get over you One more last chance Whenever you come around Little Adriana Shania Twain: Still the one Whoʼs bed have your boots been under Any man of mine From this moment on No one needs to know Brooks and Dunn: Neon moon Rock my world My Maria Boot scootin boogie Brand new man Red dirt road Hillbilly delux Long goodbye Believe Getting better all the time George strait All my exes Fireman The chair Check yes or no Amarillo by morning Ocean front property Carrying your love with me Write this down Loves gonna make it Blake Shelton God gave me you Boys round here Home Neon light Some beach Old red Sangria Turning me on Who are you when Iʼm not looking Lonely tonight Toby Keith: Shoulda been a cowboy Red solo cup -

Chartpdf Draft

"NEWS! "SPIN ZONE ! "SINGLES CALENDAR! "CHART DATA ! "NO. 1 SONG! VOICES OF SECONDARY RADIO! " COVERING THE SECONDARY RADIO MARKET SINCE 2002 REPORTING ! PANEL! Thursday, October 23, 2014 " CHART NEWS SPIN ZONE " " RaeLynn Previews Music for MusicRow Top Ten— Keith Urban is at the No. 1 spot this week with RaeLynn previewed “God Made “Somewhere In My Car.” Blake Shelton’s “Neon Light” is up Girls,” as well as several other songs, during a recent visit with one spot to No. 2 followed by Jason Aldean, also up one, with MusicRow at Big Machine’s “Burnin’ It Down” at No. 3. Maddie & Tae gain two spots with Nashville ofices. She wrapped the “Girl In A Country Song” landing at No. 4. Scotty McCreery’s performance with a quirky “Feelin’ It” remains at No. 5 for another week. Brad Paisley rendition of the mega-popular “All jumps three spots with “Perfect Storm” at No. 6. Rascal Flatts About That Bass,” penned by her singer-songwriter friend Meghan remain at No. 7 with “Payback” and Frankie Ballard sits Trainor. To see the video from the again at No. 8 with “Sunshine & Whiskey.” Tim McGraw’s visit, click HERE. “Shotgun Rider” breaks the Top Ten and lands at No. 9. Brothers Osborne remain at No. 10 with “Rum.” … " McAnally Receives No. 1 Challenge Coins Greatest Gainers— Florida Georgia Line make their debut Hit Songwriter Shane on the chart with “Sun Daze” and had the highest gain with McAnally visited MusicRow 452 new spins. Toby Keith also makes his debut with “Drunk to receive his No. -

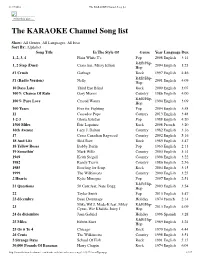

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat.