Criminal Justice System: Aims and Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

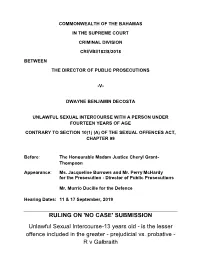

'NO CASE' SUBMISSION Unlawful Sexual Intercourse-13 Years Old - Is the Lesser Offence Included in the Greater - Prejudicial Vs

COMMONWEALTH OF THE BAHAMAS IN THE SUPREME COURT CRIMINAL DIVISION CRI/VBI/182/8/2018 BETWEEN THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS -V- DWAYNE BENJAMIN DECOSTA UNLAWFUL SEXUAL INTERCOURSE WITH A PERSON UNDER FOURTEEN YEARS OF AGE CONTRARY TO SECTION 10(1) (A) OF THE SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT, CHAPTER 99 Before: The Honourable Madam Justice Cheryl Grant- Thompson Appearance: Ms. Jacqueline Burrows and Mr. Perry McHardy for the Prosecution - Director of Public Prosecutions Mr. Murrio Ducille for the Defence Hearing Dates: 11 & 17 September, 2019 RULING ON 'NO CASE' SUBMISSION Unlawful Sexual Intercourse-13 years old - is the lesser offence included in the greater - prejudicial vs. probative - R v Galbraith Headnote: Regina v Dwayne Benjamin DeCosta Indictment No. 182/8/2018 Supreme Court Grant-Thompson J Brief Facts: The Defendant Dwayne DeCosta was charged with the Unlawful Sexual Intercourse of A.B. (a juvenile), contrary to section 10(1)(a) Sexual Offences Act, Ch. 99. The virtual complainant was declared an adverse witness in the Trial. She said he did nothing sexual to her. A.B. said she threw water in her mother's bed on the morning of the incident. Her mother dropped her off to her dad. The dad was on a cruise. A neighbour took her to the East Street South Police Station on 14 July 2018. It was a Saturday. The defendant was at work. He accepts he took her outside the station. She said they went upstairs outside the building. She claims (adversely) that nothing happened in the vacant room upstairs. There was recent complaint - a female Sergeant who saw her return looking distressed. -

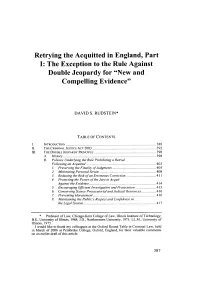

Retrying the Acquitted in England, Part I: the Exception to the Rule Against Double Jeopardy for "New and Compelling Evidence"

Retrying the Acquitted in England, Part I: The Exception to the Rule Against Double Jeopardy for "New and Compelling Evidence" DAVID S. RUDSTEIN* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. IN TRO DU C T ION .................................................................................................. 3 8 8 I1. THE CRIM INAL JUSTICE A CT 2003 ..................................................................... 392 I11. THE DOUBLE JEOPARDY PRINCIPLE .................................................................... 398 A . H istory ..................................................................................................... 3 9 8 B. Policies Underlying the Rule Prohibitinga Retrial Following an A cquittal ............................................................................ 403 1. Preservingthe Finalityof Judgments ............................................... 405 2. M inimizing PersonalStrain .............................................................. 408 3. Reducing the Risk of an Erroneous Conviction ................................. 411 4. Protectingthe Power of the Jury to Acquit Against the E vidence ......................................................................... 4 14 5. EncouragingEfficient Investigation and Prosecution ...................... 415 6. Conserving Scarce Prosecutorialand Judicial Resources................ 416 7. PreventingH arassment ..................................................................... 4 16 8. Maintainingthe Public's Respect and Confidence in the L egal System .............................................................................. -

Consideration of Applications for Bail and No Case Submission in The

Protocol I feel delighted and indeed, honoured to be invited as a resource person at this convocation of learned minds. My sincere thanks goes to the indefatigable, elegant and visionary Administrator of the National Judicial Institute, Hon. Justice R.P.I. Bozimo OFR, her management team and staff who have ensured that the standard of training offered by this Institute is maintained, in conformity with current trends in the legal profession and in the administration of justice in Nigeria. My thanks is also extended to my Chief Judge, Hon. Justice Iorhemen Hwande OFR who has graciously released me to function at this programme. Introduction The topic of my paper is ‘Consideration of Application for Bail and No Case Submission in the Magistrates’ Court.’ Without doubt, the topic has a ring of familiarity in the daily discharge of your magisterial duties at your various jurisdictions. Since it is a familiar topic, my job is made easier as I expect us to interact freely in discussing the topic and share your experiences in your various courts. As you can see, the topic addresses two different subjects in criminal law, namely: “Application for Bail” and “No Case Submission.” In this discourse I will address both subjects one after the other as they relate to practice and procedure in the Magistrates’ Court. The Meaning of “Bail” The word “Bail” according to Blacks Law Dictionary Eighth Edition is: “A security such as cash or bond, especially required by a court for the release of a prisoner who must appear at a future time.” (p. 150) The main purpose of bail therefore is to secure the presence of the accused person for his trial. -

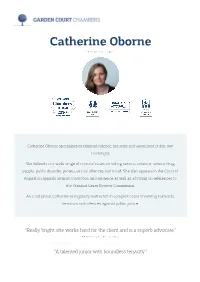

Catherine Oborne

Catherine Oborne YEAR OF CALL: 2011 Catherine Oborne specialises in criminal defence, inquests and associated public law challenges. She defends in a wide range of criminal cases including serious violence, serious drug supply, public disorder, protest, sexual offences and fraud. She also appears in the Court of Appeal on appeals against conviction and sentence as well as advising on references to the Criminal Cases Review Commission. As a led junior, Catherine is regularly instructed in complex cases involving homicide, terrorism and offences against public justice. "Really bright, she works hard for the client and is a superb advocate." CHAMBERS UK, 2021 (CRIME) "A talented junior with boundless tenacity." LEGAL 500, 2021 (CRIME) “She works really hard and is a pleasure to deal with. She’s incredibly impressive, really dedicated and extremely bright.” CHAMBERS UK, 2020 "A powerhouse: clever, committed and a fighter who leaves no stone unturned." LEGAL 500, 2020 "A great young barrister with a bright future who works amazingly hard." LEGAL 500, 2019 If you would like to get in touch with Catherine please contact the clerking team: [email protected] | +44 (0)20 7993 7600 You can also contact Catherine directly: +44 (0)20 7 7993 7824 CRIMINAL DEFENCE Catherine defends in a wide range of high-profile criminal cases including: serious violence serious drug supply public disorder protest fraud As a led junior, she is regularly instructed in complex cases involving homicide, terrorism and offences against public justice. Recent significant cases have included complex legal issues involving anonymous witnesses, closed proceedings due to national security considerations, and witnesses from MI5 giving evidence. -

Court Teasers

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. I } i ~ \ 1 COURT TEASERS Practical Situations Arising in Magistrates· Courts BY MILES McCOLL, Solicitor Clerk to the Leigh Justices ~....m_;q_r------ SB~ 0-85992-155-7 1978 C.M. McColl Published by Barry Rose (Publishers) Ltd. Little London, Chichester West Sussex Printed by The Southern Post Ltd. London Road, Bognor Regis, Sussex Criminal Law Act 1977 All provisions, except s.47, of this Act which are referred to in the text were brought into force on or before July 17 1978. ,Any reference in the text to 'an indictable offence dealt with summarily' should be construed as the summary trial of an offence triable either-way. Any reference to 'indictable offence' means an offence which, if committed by an adult, is triable on indictment, whether it is exclusively so triable or triable either-way. Any reference to a 'summary offence' means an offence which, if committed by an adult, is triable only summarily. 'Offence triable either-way' means an offence which, if committed by an adult, is triable either on indictment or summarily. (C.L. A. , 1977, s.64). iii ~~~---------.---------~----- --------------~--~-- t f; t t PREFACE t·" ~! I Although most magistrates are, by virtue of their office, lay persons, they must at all times be aware of the kind of problems which occur in their courts, in order to do justice to their important judicial appointment. In this booklet I have tried to set out in question-and-answer form, examples of the types of situation which often give cause for concern in magistrates' courts solely because the words of the relevant statutes or the decisions of the appeal courts are not closely followed. -

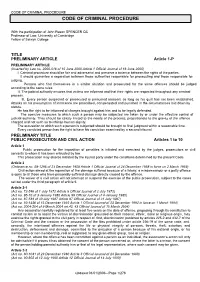

Code of Criminal Procedure Code of Criminal Procedure

CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE With the participation of John Rason SPENCER QC Professor of Law, University of Cambridge Fellow of Selwyn College TITLE PRELIMINARY ARTICLE Article 1-P PRELIMINARY ARTICLE (Inserted by Law no. 2000-516 of 15 June 2000 Article 1 Official Journal of 16 June 2000) I. Criminal procedure should be fair and adversarial and preserve a balance between the rights of the parties. It should guarantee a separation between those authorities responsible for prosecuting and those responsible for judging. Persons who find themselves in a similar situation and prosecuted for the same offences should be judged according to the same rules. II. The judicial authority ensures that victims are informed and that their rights are respected throughout any criminal process. III. Every person suspected or prosecuted is presumed innocent as long as his guilt has not been established. Attacks on his presumption of innocence are proscribed, compensated and punished in the circumstances laid down by statute. He has the right to be informed of charges brought against him and to be legally defended. The coercive measures to which such a person may be subjected are taken by or under the effective control of judicial authority. They should be strictly limited to the needs of the process, proportionate to the gravity of the offence charged and not such as to infringe human dignity. The accusation to which such a person is subjected should be brought to final judgment within a reasonable time. Every convicted person has the right to have his conviction examined by a second tribunal. -

Fourth Section the Facts

FOURTH SECTION Application no. 25424/09 by Lorraine ALLEN against the United Kingdom lodged on 29 April 2009 STATEMENT OF FACTS THE FACTS 1. The applicant, Ms Lorraine Allen, is a British national who was born in 1969 and lives in Scarborough. She is represented before the Court by Mr M. Pemberton, a lawyer practising in Wigan. A. The circumstances of the case 2. The facts of the case, as submitted by the applicant, may be summarised as follows. 1. The applicant’s conviction and appeal 3. On 7 September 2000 the applicant was convicted by a jury at Nottingham Crown Court of the manslaughter of her four-month old son, Patrick. She was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. Evidence was given at her trial by expert medical witnesses who described how the injuries suffered by her son were consistent with shaking or an impact. The conviction was based on the accepted hypothesis concerning “shaken baby syndrome”, also knows as “non-accidental head injury” (“NAHI”), to the effect that the findings of a triad of intracranial injuries consisting of encephalopathy, subdural haemorrhages and retinal haemorrhages were either diagnostic of, or at least very strongly suggestive of, the use of 2 ALLEN v. THE UNITED KINGDOM – STATEMENT OF FACTS AND QUESTIONS unlawful force. All three were present in the case of the death of the applicant’s son. 4. Following a review of cases in which expert medical evidence had been relied upon, the applicant applied for, and was granted, leave to appeal out of time. The appeal was based on a challenge to the accepted hypothesis concerning NAHI on the basis that new medical evidence suggested that the triad of injuries could be attributed to a cause other than NAHI. -

Business in Context BUSS

TRAN A803BF Hong Kong Legal System and Legal English Lecture 8 – How Law is Proceed 1 8.1 Criminal Trial 8.1.1 Introduction The usual procedures to trial are as follows: • Arrest The police arrests a suspect. • Laying of charges After investigation, the police may lay charge on the suspected. • The police shall bring the suspect to the court for trial. Then the suspected becomes an accused. The accused can choose to act in person or to engage a lawyer. 2 8.1 Criminal Trial • Criminal trials may take place in --Magistrates Court, --District Court or --Court of First Instance . The location of the trial is determined by the category of offence. However, all suspected, regardless of the category of offence, will initially come to the Magistrate Court. 3 8.1 Criminal Trial • 3 categories of offence: (a) Indictable only --The most serious crimes, e.g. murder, manslaughter, armed robbery, rape and drug trafficking involving large quantities of drugs, must be tried in the Court of First Instance before a judge and a jury. All these offences carry a maximum penalty of life imprisonment. 4 8.1 Criminal Trial --The trial of these cases may be preceded by a committal hearing in the Magistrates Court where the basic facts are tested. It is to determine whether the matter should proceed to the Court of First Instance for trial. --The committal seeks to establish whether the prosecution has sufficient evidence on which to base its charge(s )and that if the matter goes to trial that there is the likelihood that the offender will be convicted. -

Prosecution Appeals of Court-Ordered Midtrial Acquittals: Permissible Under the Double Jeopardy Clause?

Catholic University Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Fall 2012 Article 3 2012 Prosecution Appeals of Court-Ordered Midtrial Acquittals: Permissible Under the Double Jeopardy Clause? David S. Rudstein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Part of the Common Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation David S. Rudstein, Prosecution Appeals of Court-Ordered Midtrial Acquittals: Permissible Under the Double Jeopardy Clause?, 62 Cath. U. L. Rev. 91 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol62/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prosecution Appeals of Court-Ordered Midtrial Acquittals: Permissible Under the Double Jeopardy Clause? Cover Page Footnote Professor of Law and Co-Director, Program in Criminal Litigation, Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology; B.S., University of Illinois, 1968; J.D., Northwestern University, 1971; L.L.M., University of Illinois, 1975. This article is available in Catholic University Law Review: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol62/iss1/3 PROSECUTION APPEALS OF COURT-ORDERED MIDTRIAL ACQUITTALS: PERMISSIBLE UNDER THE DOUBLE JEOPARDY CLAUSE? David S. Rudstein+ I. THE ENGLISH MODEL ........................................................................................ -

Criminal Proceedings and Defence Rights in Scotland

CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS AND DEFENCE RIGHTS IN SCOTLAND This leaflet covers: Information about Fair Trials Definitions of key legal terms Information about criminal proceedings and defence rights in Scotland Useful links This booklet was last updated in March 2015 1 About Fair Trials Fair Trials is a non-governmental organisation that works for the right to a fair trial according to internationally-recognised standards of justice. Our vision is a world where every person’s right to a fair trial is respected. We believe the right to a fair trial is an essential part of a just society. Each person accused of a crime should have their guilt or innocence determined by a fair and effective legal process. But the right to a fair trial is not just about protecting suspects and defendants; it also makes societies safer and stronger. Without fair trials, trust in justice and in government collapses. Despite the importance of fair trials being recognised by the international community, this basic human right is being abused day-in-day-out in countries across the globe. We’re working to put an end to these abuses, towards realising our vision of a world where every person’s right to a fair trial is respected. If you think an important question is not covered by this note, please let us know. We would appreciate it if you could also take a few moments to give us some feedback about this note. Your comments will help us to improve our services. “Fair Trials” includes Fair Trials International and Fair Trials Europe. -

Private Prosecutions: a Potential Anticorruption Tool in English Law

LEGAL REMEDIES FOR GRAND CORRUPTION Private Prosecutions: A Potential Anticorruption Tool in English Law Tamlyn Edmonds & David Jugnarain May 2016 This paper is the fourth in a series examining the challenges and opportunities facing civil society groups that seek to develop innovative legal approaches to expose and punish grand corruption. The series has been developed from a day of discussions on the worldwide legal fight against high-level corruption organized by the Justice Initiative and Oxford University’s Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict, held in June 2014. LEGAL REMEDIES FOR GRAND CORRUPTION Tamlyn Edmonds is a founding director at Edmonds Marshall McMahon (EMM), the first and only specialist private prosecution law firm in the UK. David Jugnarain is a barrister at EMM. Published by Open Society Foundations th 224 West 57 Street New York, New York, 10019 USA Contact: Ken Hurwitz Senior Legal Officer Anticorruption Open Society Justice Initiative [email protected] LEGAL REMEDIES FOR GRAND CORRUPTION I. What is a private prosecution? The concept of “private prosecution” is unfamiliar to many. It is, put simply, a criminal prosecution pursued by a private person or body and not by a statutory prosecuting authority. The right to pursue a private prosecution is a remnant of legal history, but it remains an important one in England & Wales, the jurisdiction discussed here. In the majority of jurisdictions around the world, the criminal justice system is seen to be a function of the state, which investigates and prosecutes alleged offenders on behalf of the public and for the benefit of the public. -

The Non Bis in Idem Principle)

Factsheet – Non bis in idem July 2021 This Factsheet does not bind the Court and is not exhaustive Right not to be tried or punished twice (the non bis in idem principle) Article 4 (Right not to be tried or punished twice) of Protocol No. 7 to the European Convention on Human Rights1: “1. No one shall be liable to be tried or punished again in criminal proceedings under the jurisdiction of the same State for an offence for which he has already been finally acquitted or convicted in accordance with the law and penal procedure of that State. 2. The provisions of the preceding paragraph shall not prevent the reopening of the case in accordance with the law and penal procedure of the State concerned, if there is evidence of new or newly discovered facts, or if there has been a fundamental defect in the previous proceedings, which could affect the outcome of the case. 3. No derogation from this Article shall be made under Article 15 of the Convention.” Scope Article 4 of Protocol No. 7 limits the scope of the guarantees afforded in relation to criminal offences for the purposes of the Convention. The Court’s established case-law sets out three criteria, commonly known as the “Engel criteria”2, to be considered in determining whether or not there was a “criminal charge” (Article 6 (right to a fair trial) of the Convention). The first criterion is the legal classification of the offence under national law, the second is the very nature of the offence and the third is the degree of severity of the penalty that the person concerned risks incurring.