Court Teasers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

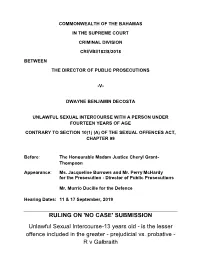

'NO CASE' SUBMISSION Unlawful Sexual Intercourse-13 Years Old - Is the Lesser Offence Included in the Greater - Prejudicial Vs

COMMONWEALTH OF THE BAHAMAS IN THE SUPREME COURT CRIMINAL DIVISION CRI/VBI/182/8/2018 BETWEEN THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS -V- DWAYNE BENJAMIN DECOSTA UNLAWFUL SEXUAL INTERCOURSE WITH A PERSON UNDER FOURTEEN YEARS OF AGE CONTRARY TO SECTION 10(1) (A) OF THE SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT, CHAPTER 99 Before: The Honourable Madam Justice Cheryl Grant- Thompson Appearance: Ms. Jacqueline Burrows and Mr. Perry McHardy for the Prosecution - Director of Public Prosecutions Mr. Murrio Ducille for the Defence Hearing Dates: 11 & 17 September, 2019 RULING ON 'NO CASE' SUBMISSION Unlawful Sexual Intercourse-13 years old - is the lesser offence included in the greater - prejudicial vs. probative - R v Galbraith Headnote: Regina v Dwayne Benjamin DeCosta Indictment No. 182/8/2018 Supreme Court Grant-Thompson J Brief Facts: The Defendant Dwayne DeCosta was charged with the Unlawful Sexual Intercourse of A.B. (a juvenile), contrary to section 10(1)(a) Sexual Offences Act, Ch. 99. The virtual complainant was declared an adverse witness in the Trial. She said he did nothing sexual to her. A.B. said she threw water in her mother's bed on the morning of the incident. Her mother dropped her off to her dad. The dad was on a cruise. A neighbour took her to the East Street South Police Station on 14 July 2018. It was a Saturday. The defendant was at work. He accepts he took her outside the station. She said they went upstairs outside the building. She claims (adversely) that nothing happened in the vacant room upstairs. There was recent complaint - a female Sergeant who saw her return looking distressed. -

CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS at COMMON LAW Edwin R

[Vol. 102 CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS AT COMMON LAW Edwin R. Keedy t GENERAL PRINCIPLES Much has been written on the law of attempts to commit crimes 1 and much more will be written for this is one of the most interesting and difficult problems of the criminal law.2 In many discussions of criminal attempts decisions dealing with common law attempts, stat- utory attempts and aggravated assaults, such as assaults with intent to murder or to rob, are grouped indiscriminately. Since the defini- tions of statutory attempts frequently differ from the common law concepts,8 and since the meanings of assault differ widely,4 it is be- "Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Pennsylvania. 1. See Beale, Criminal Attempts, 16 HARv. L. REv. 491 (1903); Hoyles, The Essentials of Crime, 46 CAN. L.J. 393, 404 (1910) ; Cook, Act, Intention and Motive in the Criminal Law, 26 YALE L.J. 645 (1917) ; Sayre, Criminal Attempts, 41 HARv. L. REv. 821 (1928) ; Tulin, The Role of Penalties in the Criminal Law, 37 YALE L.J. 1048 (1928) ; Arnold, Criminal Attempts-The Rise and Fall of an Abstraction, 40 YALE L.J. 53 (1930); Curran, Criminal and Non-Criminal Attempts, 19 GEo. L.J. 185, 316 (1931); Strahorn, The Effect of Impossibility on Criminal Attempts, 78 U. OF PA. L. Rtv. 962 (1930); Derby, Criminal Attempt-A Discussion of Some New York Cases, 9 N.Y.U.L.Q. REv. 464 (1932); Turner, Attempts to Commit Crimes, 5 CA=. L.J. 230 (1934) ; Skilton, The Mental Element in a Criminal Attempt, 3 U. -

Peter Rowlands

Peter Rowlands YEAR OF CALL: 1990 Peter Rowlands has an established reputation as a tough and committed advocate and experienced leader in criminal defence work. He has a wide-ranging practice from homicide where he acts as leading junior or sole counsel to serious sexual offences, major drug importations, fraud and money-laundering. Peter is ranked for crime in Chambers UK 2019 and the Legal 500 2019. "A decent and fair opponent who is fazed by nothing." "A wonderful advocate who you can listen to all day, he is great with juries and clients. He's the archetypical jury advocate." CHAMBERS UK, 2021 (CRIME) "His thorough case preparation, unrivalled knowledge of the law and relaxed character enables clients to firstly understand and then thoroughly trust his advice and guidance." LEGAL 500, 2021 (CRIME) "His deft and intelligent cross-examination is a joy to observe." LEGAL 500, 2020 "He defends in gang and organised crime-related cases." LEGAL 500, 2019 Extremely thorough and committed, a skilled tactician and incredibly eloquent." LEGAL 500, 2017 If you would like to get in touch with Peter please contact the clerking team: [email protected] | +44 (0)20 7993 7600 CRIMINAL DEFENCE Peter Rowlands has an established reputation as a tough and committed advocate and experienced leader in criminal defence work. He has a wide-ranging practice from homicide where he acts as leading junior or sole counsel to serious sexual offences, major drug importations, fraud and money-laundering, including contested confiscation proceedings. He has been mentioned in the Legal 500 as having developed a particular expertise in murder and armed kidnapping cases and has maintained a ranking in Chambers UK Bar Guide for many years. -

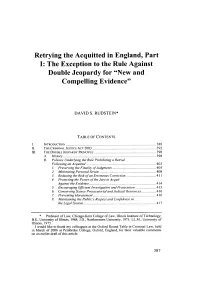

Retrying the Acquitted in England, Part I: the Exception to the Rule Against Double Jeopardy for "New and Compelling Evidence"

Retrying the Acquitted in England, Part I: The Exception to the Rule Against Double Jeopardy for "New and Compelling Evidence" DAVID S. RUDSTEIN* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. IN TRO DU C T ION .................................................................................................. 3 8 8 I1. THE CRIM INAL JUSTICE A CT 2003 ..................................................................... 392 I11. THE DOUBLE JEOPARDY PRINCIPLE .................................................................... 398 A . H istory ..................................................................................................... 3 9 8 B. Policies Underlying the Rule Prohibitinga Retrial Following an A cquittal ............................................................................ 403 1. Preservingthe Finalityof Judgments ............................................... 405 2. M inimizing PersonalStrain .............................................................. 408 3. Reducing the Risk of an Erroneous Conviction ................................. 411 4. Protectingthe Power of the Jury to Acquit Against the E vidence ......................................................................... 4 14 5. EncouragingEfficient Investigation and Prosecution ...................... 415 6. Conserving Scarce Prosecutorialand Judicial Resources................ 416 7. PreventingH arassment ..................................................................... 4 16 8. Maintainingthe Public's Respect and Confidence in the L egal System .............................................................................. -

Criminal Law Level: 6 Credit Value: 15

2021 UNIT SPECIFICATION Title: (Unit 3) Criminal Law Level: 6 Credit Value: 15 Learning outcomes Assessment criteria Knowledge, understanding and skills The learner will: The learner can: 1. Understand the 1.1 Analyse the general nature of the actus 1.1 Features to include: conduct (including fundamental reus voluntariness, i.e, R v Larsonneur (1933), requirements of Winzar v Chief Constable of Kent (1983); criminal liability • relevant circumstances; • prohibited consequences; • requirement to coincide with mens rea. 1.2 Analyse the rules of causation 1.2 Factual causation; • legal causation: situations (for example, in the context of the non-fatal offences or homicide) where the consequence is rendered more serious by the victim’s own behaviour or by the act of a third party; • approaches to establishing rules of causation: mens rea approach; This specification is for 2021 examinations • policy approach; • relevant case law to include: R v White (1910), R v Jordan (1956) R v Cheshire (1991), R v Blaue (1975), R v Roberts (1971), R v Pagett (1983), R v Kennedy (no 2) (2007), R v Wallace (Berlinah) (2018) and developing caselaw. 1.3 Analyse the status of omissions 1.3 Circumstances in which an omission gives rise to liability; • validity of the act/omission distinction; • rationale for restricting liability for omissions; • relevant case law to include: R v Pittwood (1902), R v Instan (1977), R v Miller (1983), Airedale NHS Trust v Bland (1993) Stone & Dobinson (1977), R v Evans (2009) and developing caselaw. 1.4 Analyse the meaning of intention 1.4 S8 Criminal Justice Act 1967; • direct intention; • oblique intention: definitional interpretation; • evidential interpretation; • implications of each interpretation; • concept of transferred malice; • relevant case law to include: R v Steane (1947), Chandler v DPP (1964), R v Nedrick (1986), R v Woollin (1999), Re A (conjoined twins) (2000), R v Matthews and Alleyne (2003), R v Latimer (1886), R v Pembliton (1874), R v Gnango (2011) and developing caselaw. -

Criminal Law Robbery & Burglary

Criminal Law Robbery & Burglary Begin by identifying the defendant and the behaviour in question. Then consider which offence applies: Robbery – Life imprisonment (S8(2) Theft Act 1968) Burglary – 14 years imprisonment (S9(1)(a) or S9(1)(b) Theft Act 1968) Robbery (S8(1) Theft Act 1968) Actus Reus: •! Stole (Satisfies the AR of Theft) •! Used or threatened force on any person →! R v Dawson – ‘Force’ is a word in ordinary use and it is a matter for the jury in each case to determine whether force had been used (or threatened) – but it need not be significant →! R v Clouden – Force may be applied to someone’s property →! S8(1) Theft Act 1968 – May be in relation to any person, but in regards to 3rd parties, they must be aware of the threat •! Force or threat of force was immediately before or at the time of the theft; and →! R v Hale – If appropriation was continuing and force was used at the time of the theft, the defendants could be guilty of robbery (jury’s decision) •! Force or threat of force was used in order to steal →! R v Vinall – Convictions for robbery were quashed because defendants were not proven to have had an intention to permanently deprive the victim of his property at the point when force was used on the victim Criminal Law Mens Rea: •! MR for Theft i.e. dishonesty and intention to permanently deprive •! Intention as to the use or threat of force Burglary Criminals who are ‘armed’ when they commit an offence of burglary can also face liability for an aggravated offence of burglary under S10 Theft Act 1968. -

Consideration of Applications for Bail and No Case Submission in The

Protocol I feel delighted and indeed, honoured to be invited as a resource person at this convocation of learned minds. My sincere thanks goes to the indefatigable, elegant and visionary Administrator of the National Judicial Institute, Hon. Justice R.P.I. Bozimo OFR, her management team and staff who have ensured that the standard of training offered by this Institute is maintained, in conformity with current trends in the legal profession and in the administration of justice in Nigeria. My thanks is also extended to my Chief Judge, Hon. Justice Iorhemen Hwande OFR who has graciously released me to function at this programme. Introduction The topic of my paper is ‘Consideration of Application for Bail and No Case Submission in the Magistrates’ Court.’ Without doubt, the topic has a ring of familiarity in the daily discharge of your magisterial duties at your various jurisdictions. Since it is a familiar topic, my job is made easier as I expect us to interact freely in discussing the topic and share your experiences in your various courts. As you can see, the topic addresses two different subjects in criminal law, namely: “Application for Bail” and “No Case Submission.” In this discourse I will address both subjects one after the other as they relate to practice and procedure in the Magistrates’ Court. The Meaning of “Bail” The word “Bail” according to Blacks Law Dictionary Eighth Edition is: “A security such as cash or bond, especially required by a court for the release of a prisoner who must appear at a future time.” (p. 150) The main purpose of bail therefore is to secure the presence of the accused person for his trial. -

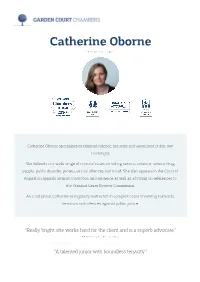

Catherine Oborne

Catherine Oborne YEAR OF CALL: 2011 Catherine Oborne specialises in criminal defence, inquests and associated public law challenges. She defends in a wide range of criminal cases including serious violence, serious drug supply, public disorder, protest, sexual offences and fraud. She also appears in the Court of Appeal on appeals against conviction and sentence as well as advising on references to the Criminal Cases Review Commission. As a led junior, Catherine is regularly instructed in complex cases involving homicide, terrorism and offences against public justice. "Really bright, she works hard for the client and is a superb advocate." CHAMBERS UK, 2021 (CRIME) "A talented junior with boundless tenacity." LEGAL 500, 2021 (CRIME) “She works really hard and is a pleasure to deal with. She’s incredibly impressive, really dedicated and extremely bright.” CHAMBERS UK, 2020 "A powerhouse: clever, committed and a fighter who leaves no stone unturned." LEGAL 500, 2020 "A great young barrister with a bright future who works amazingly hard." LEGAL 500, 2019 If you would like to get in touch with Catherine please contact the clerking team: [email protected] | +44 (0)20 7993 7600 You can also contact Catherine directly: +44 (0)20 7 7993 7824 CRIMINAL DEFENCE Catherine defends in a wide range of high-profile criminal cases including: serious violence serious drug supply public disorder protest fraud As a led junior, she is regularly instructed in complex cases involving homicide, terrorism and offences against public justice. Recent significant cases have included complex legal issues involving anonymous witnesses, closed proceedings due to national security considerations, and witnesses from MI5 giving evidence. -

“Intoxication in Criminal Law – an Analysis of the Practical Implications of the Ivey V Genting Casinos Case on the Majewski Rule”

“Intoxication in Criminal Law – An Analysis of the Practical Implications of the Ivey v Genting Casinos case on the Majewski Rule” Lucy Dougall Introduction The aim of this article is to consider the way intoxication works within criminal law, and how the application can differ depending on the category of the crime. In particular, it considers how the doctrine of intoxication applies to property offences, and how that application may be affected by the Supreme Court decision in Ivey v Genting Casinos. Due to the proportion of crimes committed containing an element of intoxication,1 it is important that the law in this area works effectively and consistently, in order for all members of the public to understand their legal position. Specifically, the law should be fair on defendants but also should be interpreted in a way that protects public safety. There have been numerous debates 2 amongst academics about the intoxication doctrine, and whether it works in the way that protects the people it should. Within England and Wales, many offenders commit crimes while under the influence of alcohol, making the law surrounding intoxication something of considerable importance. According to the March 2015 Crime Survey for England and Wales3; victims of violent incidents believed that the offenders were under the influence of alcohol in 47% of cases 4. Despite the vast amount of alcohol related violent incidents, there seems to have been a decreasing number over the last ten years. Violent incidents in general have also decreased suggesting the -

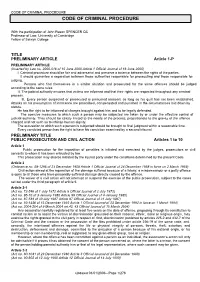

Code of Criminal Procedure Code of Criminal Procedure

CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE With the participation of John Rason SPENCER QC Professor of Law, University of Cambridge Fellow of Selwyn College TITLE PRELIMINARY ARTICLE Article 1-P PRELIMINARY ARTICLE (Inserted by Law no. 2000-516 of 15 June 2000 Article 1 Official Journal of 16 June 2000) I. Criminal procedure should be fair and adversarial and preserve a balance between the rights of the parties. It should guarantee a separation between those authorities responsible for prosecuting and those responsible for judging. Persons who find themselves in a similar situation and prosecuted for the same offences should be judged according to the same rules. II. The judicial authority ensures that victims are informed and that their rights are respected throughout any criminal process. III. Every person suspected or prosecuted is presumed innocent as long as his guilt has not been established. Attacks on his presumption of innocence are proscribed, compensated and punished in the circumstances laid down by statute. He has the right to be informed of charges brought against him and to be legally defended. The coercive measures to which such a person may be subjected are taken by or under the effective control of judicial authority. They should be strictly limited to the needs of the process, proportionate to the gravity of the offence charged and not such as to infringe human dignity. The accusation to which such a person is subjected should be brought to final judgment within a reasonable time. Every convicted person has the right to have his conviction examined by a second tribunal. -

Lalith De Kauwe

Lalith de Kauwe YEAR OF CALL: 1978 Lalith specialises in serious criminal defence. He has acted in many cases of murder, serious violence, large-scale Class A drug dealing and importation, human trafficking, public order and complex, high-value fraud. Throughout, his legal practice has been informed by his belief in social justice, civil rights and a commitment to assisting disadvantaged communities. "Lalith is a fearless defender who makes his presence known in court. He is a formidable jury advocate who fights tenaciously for his clients." MANOJ RUPASINGHE, SENIOR PARTNER, LLOYDS PR SOLICITORS "Lalith has all the skills that you could wish to find in a senior advocate. He has the ability to consistently secure acquittals against the odds." AMIR AHMAD, SOLICITOR, IMRAN KHAN AND PARTNERS SOLICITORS "Lalith is an excellent leading counsel. He stays one step ahead of the opposition whilst maintaining excellent rapport with clients." SISIRA POLPITIYA, SENIOR PARTNER, POLPITIYA & CO SOLICITORS "A fearless advocate who fights tooth and nail for his clients, no matter how big or small the case. Makes his clients comfortable and is a man of principle." SEAN NEVILLE, SOLICITOR, SATHA & CO SOLICITORS If you would like to get in touch with Lalith please contact the clerking team: [email protected] | +44 (0)20 7993 7600 You can also contact Lalith directly: +44 (0)20 7993 7722 CRIMINAL DEFENCE Lalith specialises in serious criminal defence. He has acted in many cases of murder, serious violence, large- scale Class A drug dealing and importation, human trafficking, and public order. NOTABLE CASES R v R - Successfully defended at the Central Criminal Court. -

Fourth Section the Facts

FOURTH SECTION Application no. 25424/09 by Lorraine ALLEN against the United Kingdom lodged on 29 April 2009 STATEMENT OF FACTS THE FACTS 1. The applicant, Ms Lorraine Allen, is a British national who was born in 1969 and lives in Scarborough. She is represented before the Court by Mr M. Pemberton, a lawyer practising in Wigan. A. The circumstances of the case 2. The facts of the case, as submitted by the applicant, may be summarised as follows. 1. The applicant’s conviction and appeal 3. On 7 September 2000 the applicant was convicted by a jury at Nottingham Crown Court of the manslaughter of her four-month old son, Patrick. She was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment. Evidence was given at her trial by expert medical witnesses who described how the injuries suffered by her son were consistent with shaking or an impact. The conviction was based on the accepted hypothesis concerning “shaken baby syndrome”, also knows as “non-accidental head injury” (“NAHI”), to the effect that the findings of a triad of intracranial injuries consisting of encephalopathy, subdural haemorrhages and retinal haemorrhages were either diagnostic of, or at least very strongly suggestive of, the use of 2 ALLEN v. THE UNITED KINGDOM – STATEMENT OF FACTS AND QUESTIONS unlawful force. All three were present in the case of the death of the applicant’s son. 4. Following a review of cases in which expert medical evidence had been relied upon, the applicant applied for, and was granted, leave to appeal out of time. The appeal was based on a challenge to the accepted hypothesis concerning NAHI on the basis that new medical evidence suggested that the triad of injuries could be attributed to a cause other than NAHI.