Prosecution Appeals of Court-Ordered Midtrial Acquittals: Permissible Under the Double Jeopardy Clause?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Trial and Prejudicial Publicity: a Need for Reform J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 17 | Issue 1 Article 6 1-1965 Fair Trial and Prejudicial Publicity: A Need for Reform J. Thomas McCarthy Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation J. Thomas McCarthy, Fair Trial and Prejudicial Publicity: A Need for Reform, 17 Hastings L.J. 79 (1965). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. FAIR TRIAL AND PREJUDICIAL PUBLICITY: A NEED FOR REFORM By J. THo AS McCA I* Legal trials are not like elections, to be won through the use of the meeting-hall, the radio, and the newspaper.1 Prologue: A Case in Point THE murder suspect was arrested at 1:45 Friday afternoon and taken directly to police headquarters. He was questioned intermit- tently for about twelve hours and continued to deny categorically his guilt. Consistent with its policy of allowing news representatives in the working quarters of the police building, the police made every effort to keep the press informed as to the progress of the investiga- tion. As a result, the press publicized virtually all information about the case as soon as it was uncovered by the police. Impromptu and clamorous press conferences were held in the corridor at headquarters. The Chief of Police appeared in interviews on television and radio, expressed his opinion, and gave detailed in- formation on the progress of the case. -

Double Jeopardy

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 156 DOUBLE JEOPARDY A Consultation Paper The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Carnwath CVO, Chairman Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber, QC When this consultation paper was completed on 6 September 1999, Professor Andrew Burrows was also a Commissioner. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. This consultation paper is circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views of the Law Commission. The Law Commission would be grateful for comments on this consultation paper before 31 January 2000. All correspondence should be addressed to: Mr R Percival Law Commission Conquest House 37-38 John Street Theobalds Road London WC1N 2BQ Tel: (020) 7453-1232 Fax: (020) 7453-1297 It may be helpful for the Law Commission, either in discussion with others concerned or in any subsequent recommendations, to be able to refer to and attribute comments submitted in response to this consultation paper. Any request to treat all, or part, of a response in confidence will, of course, be respected, but if no such request is made the Law Commission will assume that the response is not intended to be confidential. The text of this consultation paper is available on the Internet at: http://www.open.gov.uk/lawcomm/ Comments can be sent by e-mail to: [email protected] 17-24-01 THE LAW COMMISSION DOUBLE JEOPARDY CONTENTS [PLEASE NOTE: The pagination in this Internet version varies slightly from the hard copy published version. -

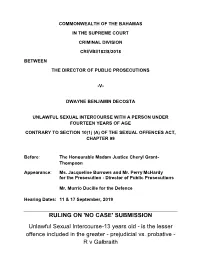

'NO CASE' SUBMISSION Unlawful Sexual Intercourse-13 Years Old - Is the Lesser Offence Included in the Greater - Prejudicial Vs

COMMONWEALTH OF THE BAHAMAS IN THE SUPREME COURT CRIMINAL DIVISION CRI/VBI/182/8/2018 BETWEEN THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS -V- DWAYNE BENJAMIN DECOSTA UNLAWFUL SEXUAL INTERCOURSE WITH A PERSON UNDER FOURTEEN YEARS OF AGE CONTRARY TO SECTION 10(1) (A) OF THE SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT, CHAPTER 99 Before: The Honourable Madam Justice Cheryl Grant- Thompson Appearance: Ms. Jacqueline Burrows and Mr. Perry McHardy for the Prosecution - Director of Public Prosecutions Mr. Murrio Ducille for the Defence Hearing Dates: 11 & 17 September, 2019 RULING ON 'NO CASE' SUBMISSION Unlawful Sexual Intercourse-13 years old - is the lesser offence included in the greater - prejudicial vs. probative - R v Galbraith Headnote: Regina v Dwayne Benjamin DeCosta Indictment No. 182/8/2018 Supreme Court Grant-Thompson J Brief Facts: The Defendant Dwayne DeCosta was charged with the Unlawful Sexual Intercourse of A.B. (a juvenile), contrary to section 10(1)(a) Sexual Offences Act, Ch. 99. The virtual complainant was declared an adverse witness in the Trial. She said he did nothing sexual to her. A.B. said she threw water in her mother's bed on the morning of the incident. Her mother dropped her off to her dad. The dad was on a cruise. A neighbour took her to the East Street South Police Station on 14 July 2018. It was a Saturday. The defendant was at work. He accepts he took her outside the station. She said they went upstairs outside the building. She claims (adversely) that nothing happened in the vacant room upstairs. There was recent complaint - a female Sergeant who saw her return looking distressed. -

In the Supreme Court State of North Dakota

FILED IN THE OFFICE OF THE CLERK OF SUPREME COURT MARCH 24, 2021 STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA IN THE SUPREME COURT STATE OF NORTH DAKOTA 2021 ND 52 State of North Dakota, Plaintiff and Appellee v. Jordan Lee Borland, Defendant and Appellant No. 20200053 Appeal from the District Court of Nelson County, Northeast Central Judicial District, the Honorable M. Jason McCarthy, Judge. AFFIRMED. Opinion of the Court by Jensen, Chief Justice. Quentin B. Wenzel (argued), Assistant State’s Attorney, Langdon, ND, and Jayme J. Tenneson (on brief), State’s Attorney, Lakota, ND, for plaintiff and appellee. Jessica J. Ahrendt, Grand Forks, ND, for defendant and appellant. State v. Borland No. 20200053 Jensen, Chief Justice. [¶1] Jordan Borland appeals from a criminal judgment entered after a jury found him guilty of criminal vehicular homicide at the conclusion of a third jury trial on the charge. Borland argues double jeopardy barred his retrial; the district court erred by denying his requested jury instruction and special verdict form seeking a jury finding on double jeopardy; and he was denied the right to a speedy trial. We affirm. I [¶2] The State charged Borland with the offense of criminal vehicular homicide on October 17, 2017. Borland’s trial was set to begin July 24, 2018. Two weeks before trial, the State requested additional trial time to present its case in order to accommodate the increased number of potential trial witnesses. Borland did not object to the State’s request to extend the length of trial. To accommodate the request for additional trial time, the district court rescheduled the trial to October 2, 2018. -

Extension of Double Jeopardy Protection to Sentencing Anne M

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 72 Article 6 Issue 4 Winter Winter 1981 Fifth Amendment--Extension of Double Jeopardy Protection to Sentencing Anne M. Pachciarek Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Anne M. Pachciarek, Fifth Amendment--Extension of Double Jeopardy Protection to Sentencing, 72 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 1276 (1981) This Supreme Court Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/81/7204-1276 THEJOURNALOF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 72, No. 4 Copyright © 1981 by Northwestern University School of Law Prinedin USA. FIFTH AMENDMENT-EXTENSION OF DOUBLE JEOPARDY PROTECTION TO SENTENCING Bullington v. Missouri, 101 S. Ct. 1852 (1981). Last term, the Supreme Court for the first time extended double jeopardy protection to a criminal defendant sentenced by a jury. In Bul'ngton v. Missouri,' the Court held that where a sentencing proceed- ing had the hallmarks of a trial on guilt or innocence, the Double Jeop- ardy Clause2 prohibited the imposition of a greater sentence at retrial. Before Bullington, the Court had refused to extend to sentencing the well- established principle that the Double Jeopardy Clause forbids the retrial of a defendant who has been acquitted of an offense. The holding in Bulngon represents a dramatic departure from the Court's longstand- ing judgment that the distinctions between a sentence and an acquittal are more critical than the similarities. -

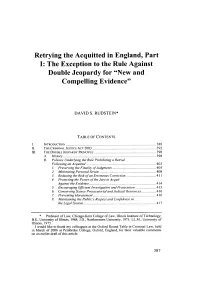

Retrying the Acquitted in England, Part I: the Exception to the Rule Against Double Jeopardy for "New and Compelling Evidence"

Retrying the Acquitted in England, Part I: The Exception to the Rule Against Double Jeopardy for "New and Compelling Evidence" DAVID S. RUDSTEIN* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. IN TRO DU C T ION .................................................................................................. 3 8 8 I1. THE CRIM INAL JUSTICE A CT 2003 ..................................................................... 392 I11. THE DOUBLE JEOPARDY PRINCIPLE .................................................................... 398 A . H istory ..................................................................................................... 3 9 8 B. Policies Underlying the Rule Prohibitinga Retrial Following an A cquittal ............................................................................ 403 1. Preservingthe Finalityof Judgments ............................................... 405 2. M inimizing PersonalStrain .............................................................. 408 3. Reducing the Risk of an Erroneous Conviction ................................. 411 4. Protectingthe Power of the Jury to Acquit Against the E vidence ......................................................................... 4 14 5. EncouragingEfficient Investigation and Prosecution ...................... 415 6. Conserving Scarce Prosecutorialand Judicial Resources................ 416 7. PreventingH arassment ..................................................................... 4 16 8. Maintainingthe Public's Respect and Confidence in the L egal System .............................................................................. -

Double Jeopardy: When Is an Acquittal an Acquittal? Jason Wiley Kent

Boston College Law Review Volume 20 Article 3 Issue 5 Number 5 7-1-1979 Double Jeopardy: When Is an Acquittal an Acquittal? Jason Wiley Kent Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Jason W. Kent, Double Jeopardy: When Is an Acquittal an Acquittal?, 20 B.C.L. Rev. 925 (1979), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/ vol20/iss5/3 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES DOUBLE JEOPARDY: WHEN IS AN ACQUITTAL AN ACQUITTAL? A fundamental principle of double jeopardy jurisprudence cautions pros- ecutors that an acquittal in a criminal case, once received, will bar forever a second prosecution for the same offense.' The notion that underlies this fifth amendinent, 2 post-acquittal protection is rudimentary to the American criminal justice system. It is that the power to prosecute, if improperly exer- cised, represents so significant a threat, to individual rights that the state must be limited to one bite at the prosecutorial apple lest the individual, innocent in the eyes of the law, be exposed to the possibility of oppressive repeated prosecutions for the same offense. 3 The relative simplicity of the concept, however, belies the complexity as- sociated with its application in clay-to-day criminal prosecutions. In reality, defendants often are discharged from prosecution following judgments that resemble in effect but not in timing or legal significance the post-trial verdict of innocence one commonly associates with the term "acquittal."' As a result, the availability of a post-acquittal double jeopardy defense has come to turn on subtle and often confusing distinctions in the manner in which the initial ' See United States v. -

Reevaluation of the United States Double Jeopardy Standard, 40 J

UIC Law Review Volume 40 Issue 1 Article 9 Fall 2006 Second Chance for Justice: Reevaluation of the United States Double Jeopardy Standard, 40 J. Marshall L. Rev. 371 (2006) Andrea Koklys Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, European Law Commons, International Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrea Koklys, Second Chance for Justice: Reevaluation of the United States Double Jeopardy Standard, 40 J. Marshall L. Rev. 371 (2006) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol40/iss1/9 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SECOND CHANCE FOR JUSTICE: REEVALUATION OF THE UNITED STATES DOUBLE JEOPARDY STANDARD ANDREA KOKLYS" I. INTRODUCTION Imagine this scenario: An eighteen-year-old woman is murdered in the United States and a man is indicted and tried for the crime. The jury grants an acquittal, but a few years later the man confesses to the murder. The United States Constitution, prevents the government from retrying this man and presenting the confession as new evidence.' Now imagine that a twenty-two- year-old woman is murdered in England. A man is tried, and the jury grants an acquittal. -

Double Jeopardy: Two-Tier Trial Systems and the Continuing Jeopardy Principle Adam N

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 75 Article 6 Issue 3 Fall Fall 1984 Fifth Amendment--Double Jeopardy: Two-Tier Trial Systems and the Continuing Jeopardy Principle Adam N. Volkert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Adam N. Volkert, Fifth Amendment--Double Jeopardy: Two-Tier Trial Systems and the Continuing Jeopardy Principle, 75 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 653 (1984) This Supreme Court Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/84/7503-653 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 75, No. 3 Copyright 0 1984 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. FIFTH AMENDMENT-DOUBLE JEOPARDY: TWO-TIER TRIAL SYSTEMS AND THE CONTINUING JEOPARDY PRINCIPLE Justices of Boston Municipal Court v. Lydon, 104 S. Ct. 1805 (1984). I. INTRODUCTION Many states have adopted criminal trial systems that allow de- fendants to choose a bench trial initially and to demand ajury trial if dissatisfied with the bench trial results. Injustices of Boston Municipal Court v. Lydon, 1 the Supreme Court held that a defendant's retrial de novo after a first-tier bench trial conviction does not violate the double jeopardy clause of the fifth amendment.2 The Supreme Court concluded that its earlier decision in Burks v. -

Double Jeopardy and Due Process Barry Siegal

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 59 | Issue 2 Article 10 1968 Double Jeopardy and Due Process Barry Siegal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Barry Siegal, Double Jeopardy and Due Process, 59 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 247 (1968) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. DOUBLE JEOPARDY when such inspection will not interfere 2. The substance or text of the charge, with Department use. such as a complaint or indictment. D. Arrest reports, arrest records, supple- 3. The identity of the investigating and mentary reports and photographs will arresting unit and the length of the not be open for inspection to representatives investigation. of the press or other news media. 4. The circumstances immediately sur- E. From the time a person is arrested until the rounding an arrest, including the time proceeding has been terminated by trial or and place of arrest, resistance, pursuit, olherwise, the following types of information possession and use of weapons, and a will not be made available to the press or news description of items seized at the time media: of arrest. 1. Observations about an arrestee's charac- G. The officer in charge of an investigation ter or prior criminal record. -

Double Jeopardy and Self-Incrimination Limitations

Michigan Law Review Volume 74 Issue 3 1976 Revocation of Conditional Liberty for the Commission of a Crime: Double Jeopardy and Self-Incrimination Limitations Michigan Law Review Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Michigan Law Review, Revocation of Conditional Liberty for the Commission of a Crime: Double Jeopardy and Self-Incrimination Limitations, 74 MICH. L. REV. 525 (1976). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol74/iss3/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES Revocation of Conditional Liberty for the Commission of a Crime: Double Jeopardy and Self-Incrimination Limitations Persons on deferred sentence, probation, or parole1 who arguably violate the criminal law may face two proceedings: a hearing to revoke their conditional liberty and a criminal trial. The possibility of two proceedings raises at least two major constitutional questions. First, are the defendant's rights under the double jeopardy or due process clauses violated if the state holds two inquiries into the alleged criminal act? Second, is the defendant's privilege against self-incrim ination abridged if the revocation hearing is held before the criminal trial? As a preliminary matter, it is necessary to delineate the constitu tional protections that have been accorded to persons on conditional liberty. -

Consideration of Applications for Bail and No Case Submission in The

Protocol I feel delighted and indeed, honoured to be invited as a resource person at this convocation of learned minds. My sincere thanks goes to the indefatigable, elegant and visionary Administrator of the National Judicial Institute, Hon. Justice R.P.I. Bozimo OFR, her management team and staff who have ensured that the standard of training offered by this Institute is maintained, in conformity with current trends in the legal profession and in the administration of justice in Nigeria. My thanks is also extended to my Chief Judge, Hon. Justice Iorhemen Hwande OFR who has graciously released me to function at this programme. Introduction The topic of my paper is ‘Consideration of Application for Bail and No Case Submission in the Magistrates’ Court.’ Without doubt, the topic has a ring of familiarity in the daily discharge of your magisterial duties at your various jurisdictions. Since it is a familiar topic, my job is made easier as I expect us to interact freely in discussing the topic and share your experiences in your various courts. As you can see, the topic addresses two different subjects in criminal law, namely: “Application for Bail” and “No Case Submission.” In this discourse I will address both subjects one after the other as they relate to practice and procedure in the Magistrates’ Court. The Meaning of “Bail” The word “Bail” according to Blacks Law Dictionary Eighth Edition is: “A security such as cash or bond, especially required by a court for the release of a prisoner who must appear at a future time.” (p. 150) The main purpose of bail therefore is to secure the presence of the accused person for his trial.