2020Csoh79.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlothian Council the Moray Council Perth & Kinross Council South

1558 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE FRIDAY 23 JULY 1999 Glenferness Proposed demolition Area Planning Office Reason for advert Application House of link corridor. 88 High Street and period for response Auldearn 99/00104/LBCNA Nairn IV124BD Listed Building Consent 99/01057/PPLB IV2 SUP Environmental and Erection of manager's house Consumer Services (in outline) on site at Ballintulm / D Rennilson, Director of Planning & Development (1601/86) 46 Leslie Street, Blairgowrie Caravan Park, Ballintulm, (21 days) Blairgowrie, Perthshire for Ballintulm Caravan Park. Midlothian Council Listed Building Consent 99/01077/LBC (21 days) Installation of sash and case windows The following application may be examined at the Community Services at Sealsbridge House, Back Street, Division, Fairfield House, 8 Lothian Road, Dalkeith EH22 3ZQ, from Bridge of Earn, Perth PH2 9AE for 9.1Sam to 4.45pm Mondays to Thursdays and from 9.15am to 3.30pm, LShaw Fridays or in the local library as indicated. Listed Building Consent 99/01098/LBC LISTED BUILDING CONSENT Environmental and Re-paint existing render at 99/00397/LBC Consumer Services Howgait, Lochgelly Road, Greenfield Lodge Erection of conservatory and alterations to 21/25 High Street, Kinross Scotlandwell, Kinross KY13 9JA Lasswade dwellinghouse. (21 days) for Dr and Mrs E Carruthers Midlothian .Local library: Bonnyrigg Listed Building Consent 99/01120/PPLB Environmental and Alterations and extension to house 'Please send any comment to me in writing not later than 13th August Consumer Services at Tirinie House, Glenfender 1999. 26 Atholl Road, Pitlochry Blair Atholl, Pitlochry G W Marwick, Director; Community Services (1601/72) (21 days) Perthshire PH185TU for Mr and Mrs D Profumo. -

Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Robert Stirling

Stirling Stuff Dr John S. Reid, Department of Physics, Meston Building, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB12 3UE, Scotland Abstract Robert Stirling’s patent for what was essentially a new type of engine to create work from heat was submitted in 1816. Its reception was underwhelming and although the idea was sporadically developed, it was eclipsed by the steam engine and, later, the internal combustion engine. Today, though, the environmentally favourable credentials of the Stirling engine principles are driving a resurgence of interest, with modern designs using modern materials. These themes are woven through a historically based narrative that introduces Robert Stirling and his background, a description of his patent and the principles behind his engine, and discusses the now popular model Stirling engines readily available. These topical models, or alternatives made ‘in house’, form a good platform for investigating some of the thermodynamics governing the performance of engines in general. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Introduction 2016 marks the bicentenary of the submission of Robert Stirling’s patent that described heat exchangers and the technology of the Stirling engine. James Watt was still alive in 1816 and his steam engine was gaining a foothold in mines, in mills, in a few goods railways and even in pioneering ‘steamers’. Who needed another new engine from another Scot? The Stirling engine is a markedly different machine from either the earlier steam engine or the later internal combustion engine. For reasons to be explained, after a comparatively obscure two centuries the Stirling engine is attracting new interest, for it has environmentally friendly credentials for an engine. This tribute introduces the man, his patent, the engine and how it is realised in example models readily available on the internet. -

William Stirling

William Stirling William Stirling was born 31 August 1841 in Forfar, Angus, Scotland. He was the second of eight children of Thomas Stirling and Elizabeth Bell, three of whom died young. In 1851, the family was living in Forfar, Scotland.1 William joined the Mormon Church in 1859.2 He was a ploughman living in Inverarity, Angus, Scotland, in 1861.3 The next year he sailed with his sister Jessie from Liverpool, England, to New York, United States, on the ship “William Tapscott”. They arrived 26 June 1862.4 They continued to the Utah Territory with the Horton D Haight Company, departing 10 August 1862 and arriving19 October 1862.5 William drove an ox team across the plains. He moved to Dixie in December 1862.6 He became a naturalized citizen.7 William married Sarah Ann Leany in 1865 in Harrisburg, Washington, Utah Territory.8 They had fourteen children.9 He built a small two-room lumber house in 1868 in Leeds, Washington, Utah Territory (the Stirling-Olsen home). He helped fund his parents and two younger sisters to immigrate to Great Salt Lake City. He was a farmer, winemaker, and the chief executive officer for the Leeds Water Company. One winter he was riding his horse through Silver Reef (a silver mining town near Leeds) and noticed a frenzy at the Christy Mill. The boilers were under full fire, but the mill stream was frozen. Knowing an explosion was inevitable if the water was unavailable to cool the mill, he quickly rode to open the head gates which directed water from the Leeds Canal.10 The owners showed their gratitude by placing William on the payroll for a year with no expectation that he would work for the salary. -

Strategic Plan

Strategic Plan Clackmannanshire and Stirling Strategic Plan 2016 - 2019 Health and Social Care Partnership Clackmannanshire and Stirling Strategic Plan Clackmannanshire and Stirling Strategic Plan Contents Foreword 2 Background to Health & Social Care Integration .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..3 .. .. .. .. .. Clackmannanshire & Stirling Health and Social Care Partnership 3 Integration Joint Board 3 Chief Officer .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..3 .. .. .. .. .. .. The Strategic Plan .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Localities .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Community Planning Partnerships 3 The Case for Change .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..4 .. .. .. Why do we need to change? 4 Profile of Clackmannanshire Council & Stirling Council Areas 4 Our Vision and Outcomes 9 Our Local Vision and Outcomes 9 Outcomes .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 How we will achieve Improved Outcomes 10 What does all of this mean for you? 11 Services working in partnership 11 Key Themes and Ambitions 12 Our -

Film & TV Locations – Stirling, Clackmannanshire, Falkirk And

Film & TV locations to visit in Stirling, Clackmannanshire, Falkirk & West Lothian search The Hippodrome, Bo'ness search Linlithgow Palace search Falkirk Wheel search Loch Katrine It’s no secret Scotland looks fantastic on the big and Falkirk is home to some truly unique experiences. Travel small screens – our stunning landscapes and brilliant on the world’s only rotating boat lift at the Falkirk Wheel, attractions have provided the backdrop to countless or discover a castle shaped like a ship at Blackness Castle. productions. Fans can immerse themselves in the real The fortress castle played the role of a prison in Outlander, deal when they visit the places they loved from the TV and fans of the show can discover various locations in and movies. Follow in the footsteps of your favourite the region. The authentic working Georgian kitchen at characters to discover these familiar locations. Callendar House featured in the series, while Muiravonside Country Park played host to the re-enactment of the Battle Some of Scotland’s best-known filming locations are in of Prestonpans. Gray Buchanan Park in Polmont also Stirling, home to infamous historic sites and breath-taking provided the backdrop for scenes in season four. Travel beauty spots. Explore castles that have starred in historic on a steam train at the Bo’ness and Kinneil Railway, which dramas which brought some of Scotland’s most famous has acted as a location in countless TV series and film figures to life. Discover Deanston Distillery, which played a productions. Learn more about Scotland’s railway heritage key role in a comedy-drama The Angels' Share, a comedy- at the largest railway museum in the country. -

Hotspots of Farm Business Diversification in Scotland

Hotspots of farm business diversification in Scotland Jonathan Hopkins1, Carla Barlagne1, Lee-Ann Sutherland1, Keith Matthews2, Andrew Barnes3, Luiza Toma3 1Social, Economic and Geographical Sciences Group, The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen 2Information and Computational Sciences Group, The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen 3Land Economy and Environment Group, Scotland’s Rural College, Edinburgh On-farm wind turbine in Aberdeenshire Purpose of document This note forms an output of Research Deliverable 2.4.2 ‘How Rural Economies Can Adapt to Key External Drivers’, undertaken as part of the RESAS Strategic Research Programme (2016-2021). This work has helped to “…identify indicators of innovation and diversification”1. This note presents an analysis of questionnaire and public datasets to identify areas in Scotland where there is evidence of high levels of farm diversification activity (‘farm diversification hotspots’). The note describes the uptake of non-farming enterprises and income diversification in Scotland, focusing in particular on renewable energy projects and agri-tourism development. Key findings • Levels of diversification are high in the rural areas north of central Scotland: Argyll, Stirling, Perth and Kinross, Fife, and Angus. • Lanarkshire and Aberdeenshire have a high concentration of on-farm renewable energy schemes, in particular onshore wind projects. • Different types of renewable energy technology tend to cluster together. In addition to onshore wind schemes (found frequently in central and eastern Scotland), hydro developments are concentrated in mountainous regions and near the west coast, and solar projects have been developed in the sunnier east (e.g. Fife, Angus). • Evidence suggests that farm diversification into agri-tourism has taken place in accessible scenic regions and in areas close to population centres. -

Highpoints Issue 11 Sàr Phuingean

The Highland Council’s Magazine Summer 2018 Highpoints Issue 11 Sàr Phuingean TThehe ttruthruth aaboutbout ttoiletsoilets PPg8g8 HHeadingeading fforor tthehe HHighlandsighlands - tthehe ttouristourist boomboom PPg4g4 Discover the HighlandAR Legends, innovative app brings augmented realityy to the city Pg14 Award winning Highland beaches Pg7g7 www.highland.gov.uk Contents 3 Highland Archaeology Festival 4 Heading for the Highlands Bill Lobban 6 Way made easier Highland Council Convener 7 Scottish beach awards 8 The truth about toilets Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of Belladrum Tartan Heart Festival, 10 New aff ordable homes underway our Highpoints magazine. the Highland Games and the 10 750th new home milestone Never has the Highlands been so Black Isle Show are all going 11 Supporting parenting skills in prison popular as a tourist destination. from strength to strength. The The value of Sterling, the long Archaeology Festival begins in 12 Grow with us spell of great weather and the September and we are delighted 13 Làithean Cultar (Culture Days) safety of the Highlands, together to be welcoming the European with the success of the NC500 Pipe Band Championships to 14 HighlandAR Legends are all contributory factors. Inverness and the Gaelic Media 16 Developing a sustainable waste solution However, the friendly welcome, Awards to Aviemore next year. our rich heritage, breath-taking Our beaches continue to attract 17 Phasing out single use plastic scenery, national parks and major awards and we have (yes) 18 Reducing our waste unique cultural off erings, makes the best public toilet provision in people fall in love with our the UK! 19 Success for Council projects beautiful region and will mean An innovative new app which 20 New role for listed building visitors will keep coming back uses augmented reality to bring 22 Apprentice has her eye on the top job for more. -

Free Piston Stirling Engines

1 Free Piston Stirling Engines The story of a novel remote power solution that helps companies improve efficiency, decrease cost and reduce emissions Dan Midea | VP Sales and Marketing Isaac Garaway | CTO John Sine | Consultant 2 A New Power Solution for Off-the-Grid Pipelines Combining a 19th Century Technology With 21st Century Power Electronics Provides Cost-Effective Power. Ever since there have been gas and oil pipelines, there has been a need for a remote power source to provide electricity for off-the-grid remote locations. And since that need first arose, there has been a competition to provide the ideal generator that could deliver the power required that was affordable and reliable. Off-Grid Solutions? Until very recently, the choices available always involved compromises and none provided a totally acceptable solution for pipeline companies. First was the obvious – expanding the grid to reach the pipeline. It was also the most expensive due to permitting cost and timeline and therefore was quickly replaced, in most instances by internal combustion engines. But they required fuel shipments and frequent maintenance and repair, often causing downtime for the wells and transmission pipelines. 3 Fortunately, a new solution has recently appeared that gives all indications of solving the most challenging problems of remote power generation. Ironically, it is based on a technology that is more than 200 years old and invented by a clergyman – the Stirling Cycle External Combustion Engine. But before we look at how this old technology has been modernized to fit the needs of the pipeline industry, we’ll look briefly at the technologies it can replace and their attendant problems. -

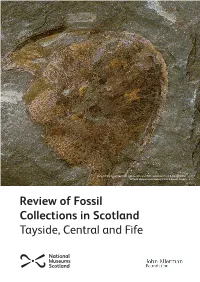

Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife

Detail of the Lower Devonian jawless, armoured fish Cephalaspis from Balruddery Den. © Perth Museum & Art Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Tayside, Central and Fife Tayside, Central and Fife Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Perth Museum and Art Gallery (Culture Perth and Kinross) The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum (Leisure and Culture Dundee) Broughty Castle (Leisure and Culture Dundee) D’Arcy Thompson Zoology Museum and University Herbarium (University of Dundee Museum Collections) Montrose Museum (Angus Alive) Museums of the University of St Andrews Fife Collections Centre (Fife Cultural Trust) St Andrews Museum (Fife Cultural Trust) Kirkcaldy Galleries (Fife Cultural Trust) Falkirk Collections Centre (Falkirk Community Trust) 1 Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum Collection type: Independent Accreditation: 2016 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, FK8 2KR Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The Smith Art Gallery and Museum, formerly known as the Smith Institute, was established at the bequest of artist Thomas Stuart Smith (1815-1869) on land supplied by the Burgh of Stirling. The Institute opened in 1874. Fossils are housed onsite in one of several storerooms. Size of collections 700 fossils. Onsite records The CMS has recently been updated to Adlib (Axiel Collection); all fossils have a basic entry with additional details on MDA cards. Collection highlights 1. Fossils linked to Robert Kidston (1852-1924). 2. Silurian graptolite fossils linked to Professor Henry Alleyne Nicholson (1844-1899). 3. Dura Den fossils linked to Reverend John Anderson (1796-1864). Published information Traquair, R.H. (1900). XXXII.—Report on Fossil Fishes collected by the Geological Survey of Scotland in the Silurian Rocks of the South of Scotland. -

Regional Improvement Collaborative Plan 2019-2022 2 Contents Contents

Forth Valley & West Lothian Regional Improvement Collaborative Plan 2019-2022 2 Contents Contents Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Introduction & Vision and Principles Of background strategic priorities Planning Building the Aligning Plans vision 4 7 13 Section 4 Section 5 Section 6 Review Of Consultation Performance and Phase 2 outcomes improvement Summary Report profile 20 23 32 Section 7 Section 8 Section 9 Delivering for the Measurement Governance and region: the next plan Reporting Plan phase 36 39 41 Appendice 1 48 Appendice 2 55 Appendice 3 59 Follow us @ #FVWLric Plan 2019-2022 Collaborative Regional Improvement 3 Section 1 Introduction & background Regional Improvement Collaborative Plan 2019-2022 Collaborative Regional Improvement 4 Introduction The Forth Valley and West Lothian Regional Improvement Collaborative (RIC) is ambitious to achieve excellence through raising attainment in all Curriculum for Excellence areas with a particular focus on numeracy and literacy. Our Improvement Collaborative will focus on closing the poverty- related attainment gap by ensuring that every child engages with the highest standards of learning and teaching to develop a range of skills, qualifications and achievements to allow them to succeed and achieve a high quality positive and sustained destination when they leave school. Our approach will be shaped by teachers, practitioners, pupils, parents and partners working together with a common purpose to give all our children and young people the highest quality educational experience and best outcomes -

Table 1 Settlements in Alphabetical Order Name Council Area 2004 Population Estimate Revised Aberchirder Aberdeenshire 1,230

Table 1 Settlements in alphabetical order 2004 Population Name Council Area Estimate Revised Aberchirder Aberdeenshire 1,230 Aberdeen, Settlement of Aberdeen City 188,760 r Aberdour Fife 1,690 r Aberfeldy Perth & Kinross 1,950 Aberfoyle Stirling 640 Aberlady East Lothian 1,100 Aberlour Moray 900 Abernethy Perth & Kinross 1,020 Aboyne Aberdeenshire 2,240 Airth Falkirk 1,460 Alford Aberdeenshire 1,950 Allanton North Lanarkshire 1,240 Alloa, Settlement of Clackmannanshire 26,350 Almondbank Perth & Kinross 1,070 Alness Highland 4,960 Alva Clackmannanshire 5,100 Alyth Perth & Kinross 2,370 r Annan Dumfries & Galloway 8,240 Annbank South Ayrshire 850 Anstruther, Settlement of Fife 5,270 Arbroath Angus 22,460 r Ardersier Highland 990 Ardrishaig Argyll & Bute 1,210 Ardrossan, Settlement of North Ayrshire 31,320 Armadale West Lothian 9,890 Auchinleck East Ayrshire 3,450 Auchterarder Perth & Kinross 3,960 Auchtermuchty Fife 2,110 Auldearn Highland 570 Aviemore Highland 2,290 Avoch Highland 1,020 Avonbridge Falkirk 660 Ayr, Settlement of South Ayrshire 60,920 Ayton Scottish Borders 570 Balfron Stirling 1,730 Balintore Highland 1,080 Ballachulish Highland 610 Ballater Aberdeenshire 1,500 Ballingry Fife 5,740 Balmedie Aberdeenshire 2,020 Balmullo Fife 1,370 Banchory Aberdeenshire 6,270 Banff Aberdeenshire 3,920 Settlements in alphabetical order 2004 Population Name Council Area Estimate Revised Bankfoot Perth & Kinross 1,220 Banknock, Settlement of Falkirk 3,220 Bathgate West Lothian 15,650 Beauly Highland 1,140 Beith North Ayrshire 6,250 Bellsbank -

Financial Aid for US Students Please Read Carefully

Financial Aid for US Students please read carefully Government Loans . The University of Stirling participates in the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program. Our school code is G10228. The loans available are: Subsidised Stafford Fixed maximum value. No interest Origination Fee 1.062% deducted at charged while in school. Disbursement. (for loans disbursed before 1st October 2019) Unsubsidised Stafford Fixed maximum value. Interest Origination Fee 1.062% deducted at charged while in school. Disbursement. (for loans disbursed before 1st October 2019) PLUS Loan (Grad PLUS or Parent Maximum value set by the Origination Fee 4.248% deducted at PLUS) University of Stirling (Cost of Disbursement. (for loans disbursed Attendance). Interest charged before 1st October 2019) while in school. You should consider the Subsidised and Unsubsidised Loans first as usually this is the cheapest way of borrowing. Please note that loan interest rates are subject to change. To keep up to date with changes to US Federal Loans please refer to the Federal Student Aid website. Eligibility for Loans . US students who are enrolled on a University of Stirling degree are eligible for loans and may borrow up to their calculated Cost of Attendance (provided by the university and updated for each year of a student’s programme). Study Abroad students from the USA studying at the University of Stirling for a semester or a full year should apply for financial aid through the financial aid office at their home university. US part-time degree students who choose to remain in the US for the duration of their studies are not eligible for Government Loans but may apply for Private Education Loans.