The Experience of Character and the Framework of an Ideal Player

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmations

007: Racing 007: The World Is Not Enough 007: Tomorrow Never Dies 101 Dalmations 2: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmations: Puppies To The Rescue 1Xtreme 2002 FIFA World Cup 2Xtreme ok 360 3D Bouncing Ball Puzzle 3D Lemmings 3Xtreme ok 3D Baseball ok 3D Fighting School 3D Kakutou Tsukuru 40 Winks ok 4th Super Robot Wars Scramble 4X4 World Trophy 70's Robot Anime Geppy-X A A1 Games: Bowling A1 Games: Snowboarding A1 Games: Tennis A Bug's Life Abalaburn Ace Combat Ace Combat 2 ok Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere ok aces of the air ok Acid Aconcagua Action Bass Action Man: Operation Extreme ok Activision Classics Actua Golf Actua Golf 2 Actua Golf 3 Actua Ice Hockey Actua Soccer Actua Soccer 2 Actua Soccer 3 Adidas Power Soccer ok Adidas Power Soccer '98 ok Advan Racing Advanced Variable Geo Advanced Variable Geo 2 Adventure Of Little Ralph Adventure Of Monkey God Adventures Of Lomax In Lemming Land, The ok Adventure of Phix ok AFL '99 Afraid Gear Agent Armstrong Agile Warrior: F-111X ok Air Combat ok Air Grave Air Hockey ok Air Land Battle Air Race Championship Aironauts AIV Evolution Global Aizouban Houshinengi Akuji The Heartless ok Aladdin In Nasiria's Revenge Alexi Lalas International Soccer ok Alex Ferguson's Player Manager 2001 Alex Ferguson's Player Manager 2002 Alien Alien Resurrection ok Alien Trilogy ok All Japan Grand Touring Car Championship All Japan Pro Wrestling: King's Soul All Japan Women's Pro Wrestling All-Star Baseball '97 ok All-Star Racing ok All-Star Racing 2 ok All-Star Slammin' D-Ball ok All Star Tennis '99 Allied General -

PRGE Nes List.Xlsx

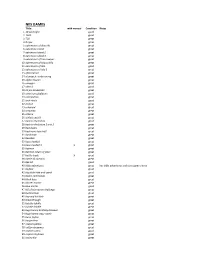

NES GAMES Tittle with manual Condition Notes 1 10 yard fight good 2 1943 great 3 720 great 4 8 eyes great 5 adventures of dino riki great 6 adventure island great 7 adventure island 2 great 8 adventure island 3 great 9 adventures of tom sawyer great 10 adventures of bayou billy great 11 adventures of lolo good 12 adventures of lolo 2 great 13 after burner great 14 al unser jr. turbo racing great 15 alpha mission great 16 amagon great 17 alien 3 good 18 all pro basketball great 19 american gladiators good 20 anticipation great 21 arch rivals good 22 archon great 23 arkanoid great 24 astyanax great 25 athena great 26 athletic world great 27 back to the future good 28 back to the future 2 and 3 great 29 bad dudes great 30 bad news base ball great 31 bards tale great 32 baseball great 33 bases loaded great 34 bases loaded 3 X great 35 batman great 36 batman return of joker great 37 battle toads X great 38 battle of olympus great 39 bee 52 good 40 bible adventures great has bible adventures exclusive game sleeve 41 bigfoot great 42 big birds hide and speak good 43 bionic commando great 44 black bass great 45 blaster master great 46 blue marlin good 47 bill elliots nascar challenge great 48 bomberman great 49 boy and his blob great 50 breakthrough great 51 bubble bobble great 52 bubble bobble great 53 bugs bunny birthday blowout great 54 bugs bunny crazy castle great 55 burai fighter great 56 burgertime great 57 caesars palace great 58 california games great 59 captain comic good 60 captain skyhawk great 61 casino kid great 62 castle of dragon great 63 castlvania great 64 castlvania 2 great 65 castlvania 3 great 66 caveman games great 67 championship bowling great 68 chessmaster great 69 chip n dale great 70 city connection great 71 clash at demonhead great 72 concentration poor game is faded and has tears to front label (tested) 73 cobra command great 74 cobra triangle great 75 commando great 76 conquest of crystal palace great 77 contra great 78 cybernoid great 79 crystal mines X great black cartridge. -

War and Play

WAR AND PLAY Insensitivity and Humanity in the Realm of Pushbutton Warfare MFA Thesis, Electronic Media Arts Design March 11, 2008 Devin Monnens Biography Devin Monnens is a game designer and critical game theorist. He graduated with an MFA degree in Electronic Media Arts Design (eMAD) from the University of Denver in 2008, researching, designing, and critiquing antiwar games. Devin has presented his research at the Southwest/Texas American and Popular Culture Association Conference and at Colorado chapter meetings of the International Game Developers Association (IGDA). An active member of the IGDA, Devin works closely with the Videogame Preservation Special Interest Group (SIG), dedicated to cataloging and preserving videogames as well as their history and culture, and also started the Game Developer Memorials SIG, which records and shares the memories of the lives and work of deceased game developers from around the world. His professional research also includes such diverse topics as narratology, gender and games, socially conscious games, and biogaming, and his work is built upon a foundation of literary theory, art history, and medieval studies. Devin strives to create games that reshape the way we imagine our world, the nature of humanity, and ourselves through the languages of play and simulation, pushing the boundaries of the medium to help games realize their potential as a means of artistic communication. This document is also available at Desert Hat http://www.deserthat.com/ INDEX Introduction 1 Defining Antiwar Games 2 Depictions -

001 300 500 002 40 60 003 150 200 004 120 150 005 200

001 Magnavox Odyssey - USA, 1972 Edition assemblée au Mexique, complète en très bon état avec les deux manettes, les layers, les 6 cartes de jeux et notices. Très bel état. Pour rappel, la Magnavox Odyssey est la première console de jeu. 300 500 002 Magnavox Odyssey 4000 - USA, 1977 En boite avec ses câbles 40 60 003 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME 6 - JAPON, 1977 Model CTG-6V #9800 Première console PONG de Nintendo n°4158465 Fourni en boite (bon état) avec câble, switch box et documentation. Bel ensemble des débuts de Nintendo. 150 200 004 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME 15 - JAPON, 1977 Model CTG-15S #15000 Seconde console PONG de Nintendo, sorti peu de temps après la CTG-6V, elle contient 15 jeux. n°2156926 Fourni en boite (abimé sur le dessous) avec câble, switch box et documentation. Trois modèles de couleur sont sortis : Jaune, Orange et Blanc. Cet exemplaire est un modèle jaune. 120 150 005 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME "Racing 112" - JAPON, 1978 En boite et notice, complet, proche du neuf, superbe pièce. Model CTG-CR112 # 5000 n°1021935 200 300 006 PONG SHG "Black Point" Type FS 1003 (1981) Console PONG Allemande programmable à cartouches, livrée en boite avec câbles et deux controllers. 20 40 007 PONG MONTEVERDI "E&P model EP500" TV Sports 825 (1976) Livré en boite, ce PONG très rare licencié par Magnavox est complet avec ses câbles, notice US et Française model n°E825A Series n° 255B Serial n°129956 60 80 008 PONG "SONESTA hide-away TV Game" (1977) En boite avec cale et câble 20 40 009 PONG International LLOYD'S TV Sports 812 (1976) En boite avec fusil, câbles et notice US + française (RARE) Belle chance d'acquérir une pièce historique. -

Sony Playstation

Sony PlayStation Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007 Racing Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 101 Dalmatians II, Disney's: Patch's London Adventure Eidos Interactive 102 Dalmatians, Disney's: Puppies to the Rescue Eidos Interactive 1Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2Xtreme SCEA 2Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 3 Game Value Pack Volume #1 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #2 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #3 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #4 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #5 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #6 Agetec (Distributed by Tommo) 3D Baseball Crystal Dynamics 3D Lemmings: Long Box Ridged Psygnosis 3Xtreme 989 Studios 3Xtreme: Demo 989 Studios 40 Winks GT Interactive A-Train: Long Box Cardboard Maxis A-Train: SimCity Card Booster Pack Maxis Ace Combat 2 Namco Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere Namco Aces of the Air Agetec Action Bass Take-Two Interactive Action Man: Operation Extreme Hasbro Interactive Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600 Activision Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600: Greatest Hits Activision Adidas Power Soccer Psygnosis Adidas Power Soccer '98 Psygnosis Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron & Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft Acclaim Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron and Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft: Demo Acclaim Adventures of Lomax, The Psygnosis Agile Warrior F-111X: Jewel Case Virgin Agile Warrior F-111X: Long Box Ridged Virgin Games Air Combat: Long Box Clear Namco Air Combat: Greatest Hits Namco Air Combat: Jewel Case Namco Air Hockey Mud Duck Akuji the Heartless Eidos Aladdin in Nasira's Revenge, Disney's Sony Computer Entertainment.. -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

Who Are Plus Alpha?

INTRODUCING PLUS ALPHA Plus Alpha Translations has been specializing in Japanese video game localization since 2002. Our experience spans many titles and genres, with a portfolio that boasts best- sellers such as Dragon Quest IX, Okami and Phoenix Wright 3. Plus Alpha Translations is not an agency. We are a small company of dedicated translators, and we never outsource our work to third parties. Quality is our first priority, and we're often praised that our work requires little or no editing. Plus Alpha Translations works both with agencies and games companies directly, in-house or remotely. We believe our close liaison with you and responsiveness to your needs are what set our company apart. We always guarantee first-class results. W H Y C H O O S E P L U S A LPHA ? + We have been translating professionally since 1999, and specializing in games since 2002. + We offer native British English, a skill that's increasingly in demand in the industry. Soccer games are a prime example, but many other genres are now tapping into BE to give their products a fresh flavour. Of course, we're also competent in American English, as you'll see from the many titles in our portfolio. + Natural English is the key to giving a localized game the power to absorb its players, and we really take this to heart in our work. Without compromising accuracy, we make a point of injecting humour and drama, so our writing stands out from the crowd. Our slogan says it all: You'd never know it started in Japanese! + If speed is of the essence, Plus Alpha can help. -

Ps1 Download Free Games

Ps1 download free games ROMs, ISOs, Games. Most Popular Sections We're sure that you know not many sites offer PSX ISO's for download. The reason for this is that it We have over PSX ROMs for you to download over here! Tons of amazing titles that Sony Playstation ISOs · Crash Bandicoot [U] · Crash Team Racing [U]. In order to play these Sony PlayStation One ISO / PSX games, you must first download an PSX emulator, which is used to load the Sony PlayStation One ISO Crash Bandicoot ROM. · Clash Of Super Heroes ROM · Final Bout ROM. 's PSX ROMs section. Browse: Top ROMs or By Letter. Mobile optimized. Europe France Germany Italy Japan Russia Spain Featured Games: 's PSX ROMs · Crash Bandicoot · Tekken 3 · Action/Platform. Roms Isos PSX, PS1, PS2, PSP, Arcade, NDS, 3DS, Wii, Gamecube, Snes, Mega drive, Nintendo 64, GBA, Dreamcast Home /Games /PS1 ISOs for download. winrar: image burn: ?act=download. Download Playstation Isos & PSX Roms @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate Retro Gaming Resource. Game Kids [NTSC-J] Redump [SLPS]. Download Playstation Isos, Playstation Roms, Homebrew, Emulators & Tools @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate PSX2PSP v (Convert PSX games to PSP). The top PSX games of all time. Download Playstation ROMs free and play on Windows, MAC, or Android Devices. We also have games you can play online! Download section for PlayStation (PSX) ROMs / ISOs of Rom Hustler. Browse ROMs / ISOs by download count and ratings. % Fast Game Name. Game, Console. >> Racing, Playstation. >> The World Is Not Enough, Playstation. >> 25 To Life, Playstation. >> 3Xtreme, Playstation. >> 40 Winks. -

Fish Richardsonp.C

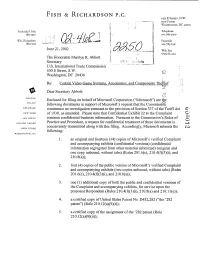

FISH RICHARDSONP.C. 1425 K STREET,N.W. .. IITH FLOOR WASHINGTON,DC 20005 Iiederick P. Fish Telephone 202 783-5070 1855-1930 W.K. Richaidson Facsimile 1859-1951 202 783-2331 June 21,2002 Web Site www.fr.com The Honorable Marilyn R. Abbott Secretary U.S. International Trade Commission .3 I 500 E Street, S.W. Nc-5 Washington, DC 20436 r . 5 Re: Certain Video Game Systems, Accessories, and Components Th&o f ’I A Dear Secretary Abbott: J -a :Ll BOSTON Enclosed for filing on behalf of Microsoft Corporation (“Microsoft”) are tlfe DALLAS following documents in support of Microsoft’s request that the Commissiz DELAWARE r”. commence an investigation pursuant to the provision of Section 337 of the Tariff Act CL NEW YORK of 1930, as amended. Please note that Confidential Exhibit 22 to the Complaint 5 SAN DIEGO contains confidential business information. Pursuant to the Commission’s Rules of ,= SILICON VALLEY Practice and Procedure, a request for confidential treatment of these documents is i.4 concurrently transmitted along with this filing. Accordingly, Microsoft submits the N TWIN CITIES following: WASHINGTON, DC 1. an original and fourteen (14) copies of Microsoft’s verified Complaint and accompanying exhibits (confidential versions) (confidential information segregated from other material submitted) (original and one copy unbound, without tabs) (Rules 201.6(c), 210.4(f)(3)(i), and 2 10.8 (a)); 2. four (4) copies of the public version of Microsoft’s verified Complaint and accompanying exhibits (two copies unbound, without tabs) (Rules 20 1.6( c), 2 10.4( f)( 3)( i) , and 2 10.8 (a)); 3. -

The Sacred & the Digital

Tilburg University The Sacred & the Digital Bosman, Frank DOI: 978-3-03897-831-2 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Bosman, F. (Ed.) (2019). The Sacred & the Digital: Critical Depictions of Religions in Video Games. MDPI AG. https://doi.org/978-3-03897-831-2 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 The Sacred & the Digital Critical Depictions of Religions in Video Games Edited by Frank G. Bosman Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions The Sacred & the Digital The Sacred & the Digital: Critical Depictions of Religions in Video Games Special Issue Editor Frank G. Bosman MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Frank G. -

45 Years of Arcade Gaming

WWW.OLDSCHOOLGAMERMAGAZINE.COM ISSUE #2 • JANUARY 2018 Midwest Gaming Classic midwestgamingclassic.com CTGamerCon .................. ctgamercon.com JANUARY 2018 • ISSUE #2 EVENT UPDATE BRETT’S BARGAIN BIN Portland Classic Gaming Expo Donkey Kong and Beauty and the Beast 06 BY RYAN BURGER 38BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF WE DROPPED BY FEATURE Old School Pinball and Arcade in Grimes, IA 45 Years of Arcade Gaming: 1980-1983 08 BY RYAN BURGER 40BY ADAM PRATT THE WALTER DAY REPORT THE GAME SCHOLAR When President Ronald Reagan Almost Came The Nintendo Odyssey?? 10 To Twin Galaxies 43BY LEONARD HERMAN BY WALTER DAY REVIEW NEWS I Didn’t Know My Retro Console Could Do That! 2018 Old School Event Calendar 45 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF 12 BY RYAN BURGER FEATURE REVIEW Inside the Play Station, Enter the Dragon Nintendo 64 Anthology 46 BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD 13 BY KELTON SHIFFER FEATURE WE STOPPED BY Controlling the Dragon A Gamer’s Paradise in Las Vegas 51 BY ANTOINE CLERC-RENAUD 14 BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF PUREGAMING.ORG INFO GAME AND MARKET WATCH Playstation 1 Pricer Game and Market Watch 52 BY PUREGAMING.ORG 15 BY DAN LOOSEN EVENT UPDATE Free Play Florida Publisher 20BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF Ryan Burger WESTOPPED BY Business Manager Aaron Burger The Pinball Hall of Fame BY OLD SCHOOL GAMER STAFF Design Director 22 Issue Writers Kelton Shiffer Jacy Leopold MICHAEL THOMASSON’S JUST 4 QIX Ryan Burger Michael Thomasson Design Assistant Antoine Clerc-Renaud Brett Weiss How High Can You Get? Marc Burger Walter Day BY MICHAEL THOMASSON 24 Brad Feingold Editorial Board Art Director KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA Todd Friedman Dan Loosen Thor Thorvaldson Leonard Herman Doc Mack Where It All Began Dan Loosen Billy Mitchell BY SHAWN PAUL JONES + WALTER DAY Circulation Manager Walter Day 26 Kitty Harr Shawn Paul Jones Adam Pratt KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA King of Kong Movie Review 28 BY BRAD FEINGOLD HOW TO REACH OLD SCHOOL GAMER: Tel / Fax: 515-986-3344 Postage paid at Grimes, IA and additional mailing KING OF KONG/OTTUMWA, IA Web: www.oldschoolgamermagazine.com locations.