War and Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIE Nächsteation UNSERE EXPERTEN TRENNEN DIE BUZZWORDS VON FAKTEN ANALYSEN UND ERKENNTNISSE VON EPIC, HAVOK UND BUNGIE

JEDE AUSGABE MIT FIRMENREGISTER 04/2013 € 6,90 OFFIZIELLER PARTNER VON DESIGN BUSINESS ART TECHNOLOGY 04 4 197050406909 GENERDIE NÄCHSTEaTION UNSERE EXPERTEN TRENNEN DIE BUZZWORDS VON FAKTEN ANALYSEN UND ERKENNTNISSE VON EPIC, HAVOK UND BUNGIE MEINUNG BEST PRACTICE INTERVIEW ICH HASSE DRM! ODER WIE SICH BEI UNITY3D-ASSETS UBISOFTS JADE RAYMOND ÜBER DOCH WAS ANDERES? RECHENLEISTUNG SPAREN LÄSST DEN NÖTIGEN ERNST IM SPIEL "PHANTASIE, NICHT ERFINDUNG, SCHAFFT IN DER KUNST WIE IM LEBEN DAS GANZ BESONDERE." Joseph Conrad Die Welt, die Sie erschaffen, soll nur durch Ihre Vorstellungskraft limitiert sein – nicht durch die Leistung Ihres Servers. Verschieben Sie Ihre Grenzen. Managed Hosting von Host Europe. Kompromisslose Rechenleistung schon ab € 89 mtl.* Managed Hosting – Rechenpower und individueller Service ▶ Dell® Markenhardware, individuell für Ihre Anforderungen konfiguriert ▶ Hosting im Hightech-Rechencenter mit garantierter Verfügbarkeit und bester Netzanbindung ▶ Managed Service mit festen Ansprechpartnern, 24/7/365 Wartung und Entstörung Mehr Informationen: i www.hosteurope.de/creation Kontakt & Beratung (Mo-Fr: 09-17 Uhr) 02203 1045 2222 www.hosteurope.de *Die einmalige Setupgebühr entfällt. Die Aktion gilt bis zum 31.07.2013. Die Hardware ist individuell konfigurierbar. Die Mindestvertragslaufzeit beträgt 24 Monate – alternative Laufzeiten sind optional möglich. Die Kündigungsfrist beträgt 4 Wochen zum Ende der Laufzeit. Editorial Making Games Magazin 04/2013 UNGERECHTE E3 ie hatten das bessere Line-up, die Next-Gen-Tipps von Havok & Epic Heiko Klinge innovativere Technologie und die Mehr als genug Gründe also, den Shitstorm ist Chefredakteur vom unterhaltsamere Show: Trotzdem mal getrost zu ignorieren und die eigentlichen Making Games Magazin. hat Microsoft das Next-Gen- Auswirkungen der Next Gen in unserem Kräftemessen mit Sony nach Mei- Titelthema ein wenig genauer unter die Lupe nung fast aller Beobachter und zu nehmen. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables. -

Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmations

007: Racing 007: The World Is Not Enough 007: Tomorrow Never Dies 101 Dalmations 2: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmations: Puppies To The Rescue 1Xtreme 2002 FIFA World Cup 2Xtreme ok 360 3D Bouncing Ball Puzzle 3D Lemmings 3Xtreme ok 3D Baseball ok 3D Fighting School 3D Kakutou Tsukuru 40 Winks ok 4th Super Robot Wars Scramble 4X4 World Trophy 70's Robot Anime Geppy-X A A1 Games: Bowling A1 Games: Snowboarding A1 Games: Tennis A Bug's Life Abalaburn Ace Combat Ace Combat 2 ok Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere ok aces of the air ok Acid Aconcagua Action Bass Action Man: Operation Extreme ok Activision Classics Actua Golf Actua Golf 2 Actua Golf 3 Actua Ice Hockey Actua Soccer Actua Soccer 2 Actua Soccer 3 Adidas Power Soccer ok Adidas Power Soccer '98 ok Advan Racing Advanced Variable Geo Advanced Variable Geo 2 Adventure Of Little Ralph Adventure Of Monkey God Adventures Of Lomax In Lemming Land, The ok Adventure of Phix ok AFL '99 Afraid Gear Agent Armstrong Agile Warrior: F-111X ok Air Combat ok Air Grave Air Hockey ok Air Land Battle Air Race Championship Aironauts AIV Evolution Global Aizouban Houshinengi Akuji The Heartless ok Aladdin In Nasiria's Revenge Alexi Lalas International Soccer ok Alex Ferguson's Player Manager 2001 Alex Ferguson's Player Manager 2002 Alien Alien Resurrection ok Alien Trilogy ok All Japan Grand Touring Car Championship All Japan Pro Wrestling: King's Soul All Japan Women's Pro Wrestling All-Star Baseball '97 ok All-Star Racing ok All-Star Racing 2 ok All-Star Slammin' D-Ball ok All Star Tennis '99 Allied General -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Secara Singkat, Perang

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Secara singkat, perang Vietnam adalah perang terpanjang dalam sejarah Amerika Serikat dan paling populer pada abad ke-20. Perang ini mengakibatkan hampir 60.000 pasukan Amerika Serikat yang menjadi korban dan sekitar 2 juta korban di pihak Vietnam. Awal mula Perang Vietnam ini adalah sekitar tahun 1953 hingga 1973 yang diawali oleh perang anti-kolonial melawan Perancis.1 Setelah Jepang menyerah kepada sekutu pada tahun 1945, Ho Chi Minh adalah seorang komunis yang menginginkan Vetnam merdeka dibawah bayang-bayang paham komunis. Akan tetapi Perancis sebagai negara yang telah menjajah Vietnam tidak menginginkan hal itu terjadi. Oleh karena itu pada tahun 1946, tentara Amerika datang untuk membantu Perancis dalam menjadikan Vietnam sebagai negara berpaham nasionalis. Namun, Amerika juga tidak mau Perancis tetap mengambil sepenuhnya dataran Vietnam.2 Oleh karena itulah untuk sementara waktu, Vietnam dibagi dua yaitu Vietnam Selatan yang berpaham Liberalis dan Vietnam Utara yang berpaham Komunis. Dari tahun 1968 hingga 1973, berbagai upaya dilakukan untuk mengakhiri konflik ini melalui diplomasi. Hingga pada akhirnya pada tahun 1973 terdapat sebuah kesepakatan yang dinama Pasukan Amerika Serikat ditarik dari Vietnam dan seluruh tawanan AS di 1The Vietnam War 1954-1975 (Chapter 26), hal. 883 diakses dalam http://www.kingherrud.com/uploads/3/7/5/9/37597419/chapter_26.pdf (28/2/2018, 09:12 WIB) 2Ibid 1 bebaskan. Pada bulan April 1975, Vietnam Selatan menyerah dan terjadilah penyatuan kembali negara Vietnam.3 -

Gender and the Games Industry: the Experiences of Female Game Workers

Gender and the Games Industry: The Experiences of Female Game Workers by Marsha Newbery BA., University of Winnipeg, 1994 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art & Technology © Marsha Newbery 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 Approval Name: Marsha-Jayne Newbery Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title of Thesis: Gender and the Games Industry: The Experiences of Female Game Workers Examining Committee: Chair: Frédérik Lesage Assistant Professor Alison Beale Senior Supervisor Professor Catherine Murray Supervisor Professor Leslie Regan Shade External Examiner Associate Professor, Faculty of Information, University of Toronto Date Defended/Approved: February 8, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or d. as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. A copy of the approval letter has been filed at the Theses Office of the University Library at the time of submission of this thesis or project. The original application for approval and letter of approval are filed with the relevant offices. Inquiries may be directed to those authorities. -

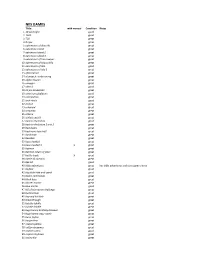

PRGE Nes List.Xlsx

NES GAMES Tittle with manual Condition Notes 1 10 yard fight good 2 1943 great 3 720 great 4 8 eyes great 5 adventures of dino riki great 6 adventure island great 7 adventure island 2 great 8 adventure island 3 great 9 adventures of tom sawyer great 10 adventures of bayou billy great 11 adventures of lolo good 12 adventures of lolo 2 great 13 after burner great 14 al unser jr. turbo racing great 15 alpha mission great 16 amagon great 17 alien 3 good 18 all pro basketball great 19 american gladiators good 20 anticipation great 21 arch rivals good 22 archon great 23 arkanoid great 24 astyanax great 25 athena great 26 athletic world great 27 back to the future good 28 back to the future 2 and 3 great 29 bad dudes great 30 bad news base ball great 31 bards tale great 32 baseball great 33 bases loaded great 34 bases loaded 3 X great 35 batman great 36 batman return of joker great 37 battle toads X great 38 battle of olympus great 39 bee 52 good 40 bible adventures great has bible adventures exclusive game sleeve 41 bigfoot great 42 big birds hide and speak good 43 bionic commando great 44 black bass great 45 blaster master great 46 blue marlin good 47 bill elliots nascar challenge great 48 bomberman great 49 boy and his blob great 50 breakthrough great 51 bubble bobble great 52 bubble bobble great 53 bugs bunny birthday blowout great 54 bugs bunny crazy castle great 55 burai fighter great 56 burgertime great 57 caesars palace great 58 california games great 59 captain comic good 60 captain skyhawk great 61 casino kid great 62 castle of dragon great 63 castlvania great 64 castlvania 2 great 65 castlvania 3 great 66 caveman games great 67 championship bowling great 68 chessmaster great 69 chip n dale great 70 city connection great 71 clash at demonhead great 72 concentration poor game is faded and has tears to front label (tested) 73 cobra command great 74 cobra triangle great 75 commando great 76 conquest of crystal palace great 77 contra great 78 cybernoid great 79 crystal mines X great black cartridge. -

Exergames and the “Ideal Woman”

Make Room for Video Games: Exergames and the “Ideal Woman” by Julia Golden Raz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christian Sandvig, Chair Professor Susan Douglas Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy Professor Lisa Nakamura © Julia Golden Raz 2015 For my mother ii Acknowledgements Words cannot fully articulate the gratitude I have for everyone who has believed in me throughout my graduate school journey. Special thanks to my advisor and dissertation chair, Dr. Christian Sandvig: for taking me on as an advisee, for invaluable feedback and mentoring, and for introducing me to the lab’s holiday white elephant exchange. To Dr. Sheila Murphy: you have believed in me from day one, and that means the world to me. You are an excellent mentor and friend, and I am truly grateful for everything you have done for me over the years. To Dr. Susan Douglas: it was such a pleasure teaching for you in COMM 101. You have taught me so much about scholarship and teaching. To Dr. Lisa Nakamura: thank you for your candid feedback and for pushing me as a game studies scholar. To Amy Eaton: for all of your assistance and guidance over the years. To Robin Means Coleman: for believing in me. To Dave Carter and Val Waldren at the Computer and Video Game Archive: thank you for supporting my research over the years. I feel so fortunate to have attended a school that has such an amazing video game archive. -

Massively Multiplayer Online Games Industry: a Review and Comparison

Massively Multiplayer Online Games Industry: A Review and Comparison From Middleware to Publishing By Almuntaser Alhindawi Javed Rafiq Sim Boon Seong 2007 A Management project presented in part consideration for the degree of "General and Financial MBA". CONFIDENTIALITY STATEMENT This project has been agreed as confidential between the students, university and sponsoring organisation. This agreement runs for five years from September, 14 th , 2007. ii Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge Monumental Games management for giving us this opportunity to gain an insight of this interesting industry. Special thanks for Sarah Davis, Thomas Chesney and the University of Nottingham Business School MBA office personnel (Elaine, Kathleen and Christinne) for their assistance and support throughout this project. We would also like to thank our families for their constant support and patience; - Abdula Alhindawi - Fatima Alhindawi - Shatha Bilbeisi - Michelle Law Seow Cha - Sim Hock Soon - Yow Lee Yong - Mohamed Rafiq - Salma Rafiq - Shama Hamid Last but not least, our project supervisor Duncan Shaw for his support and guidance throughout the duration of this management project. i Contents Executive Summary iv Terms and Definition vi 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Methodology 1 1.1.1 Primary Data Capture 1 1.1.2 Secondary Data Capture 2 1.2 Literature Review 4 1.2.1 Introduction 4 1.2.2 Competitive Advantage 15 1.2.3 Business Model 22 1.2.4 Strategic Market Planning Process 27 1.2.5 Value Net 32 2.0 Middleware Industry 42 2.1 Industry Overview 42 2.2 -

001 300 500 002 40 60 003 150 200 004 120 150 005 200

001 Magnavox Odyssey - USA, 1972 Edition assemblée au Mexique, complète en très bon état avec les deux manettes, les layers, les 6 cartes de jeux et notices. Très bel état. Pour rappel, la Magnavox Odyssey est la première console de jeu. 300 500 002 Magnavox Odyssey 4000 - USA, 1977 En boite avec ses câbles 40 60 003 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME 6 - JAPON, 1977 Model CTG-6V #9800 Première console PONG de Nintendo n°4158465 Fourni en boite (bon état) avec câble, switch box et documentation. Bel ensemble des débuts de Nintendo. 150 200 004 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME 15 - JAPON, 1977 Model CTG-15S #15000 Seconde console PONG de Nintendo, sorti peu de temps après la CTG-6V, elle contient 15 jeux. n°2156926 Fourni en boite (abimé sur le dessous) avec câble, switch box et documentation. Trois modèles de couleur sont sortis : Jaune, Orange et Blanc. Cet exemplaire est un modèle jaune. 120 150 005 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME "Racing 112" - JAPON, 1978 En boite et notice, complet, proche du neuf, superbe pièce. Model CTG-CR112 # 5000 n°1021935 200 300 006 PONG SHG "Black Point" Type FS 1003 (1981) Console PONG Allemande programmable à cartouches, livrée en boite avec câbles et deux controllers. 20 40 007 PONG MONTEVERDI "E&P model EP500" TV Sports 825 (1976) Livré en boite, ce PONG très rare licencié par Magnavox est complet avec ses câbles, notice US et Française model n°E825A Series n° 255B Serial n°129956 60 80 008 PONG "SONESTA hide-away TV Game" (1977) En boite avec cale et câble 20 40 009 PONG International LLOYD'S TV Sports 812 (1976) En boite avec fusil, câbles et notice US + française (RARE) Belle chance d'acquérir une pièce historique. -

Sony Playstation

Sony PlayStation Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 007 Racing Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough Electronic Arts 007: The World is Not Enough: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies Electronic Arts 007: Tomorrow Never Dies: Greatest Hits Electronic Arts 101 Dalmatians II, Disney's: Patch's London Adventure Eidos Interactive 102 Dalmatians, Disney's: Puppies to the Rescue Eidos Interactive 1Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 2002 FIFA World Cup Electronic Arts 2Xtreme SCEA 2Xtreme: Greatest Hits SCEA 3 Game Value Pack Volume #1 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #2 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #3 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #4 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #5 Agetec 3 Game Value Pack Volume #6 Agetec (Distributed by Tommo) 3D Baseball Crystal Dynamics 3D Lemmings: Long Box Ridged Psygnosis 3Xtreme 989 Studios 3Xtreme: Demo 989 Studios 40 Winks GT Interactive A-Train: Long Box Cardboard Maxis A-Train: SimCity Card Booster Pack Maxis Ace Combat 2 Namco Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere Namco Aces of the Air Agetec Action Bass Take-Two Interactive Action Man: Operation Extreme Hasbro Interactive Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600 Activision Activision Classics: A Collection of Activision Classic Games for the Atari 2600: Greatest Hits Activision Adidas Power Soccer Psygnosis Adidas Power Soccer '98 Psygnosis Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron & Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft Acclaim Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Iron and Blood - Warriors of Ravenloft: Demo Acclaim Adventures of Lomax, The Psygnosis Agile Warrior F-111X: Jewel Case Virgin Agile Warrior F-111X: Long Box Ridged Virgin Games Air Combat: Long Box Clear Namco Air Combat: Greatest Hits Namco Air Combat: Jewel Case Namco Air Hockey Mud Duck Akuji the Heartless Eidos Aladdin in Nasira's Revenge, Disney's Sony Computer Entertainment.. -

Cloud Gaming: L'ère Du Jeu Streamé

Future TV and Digital Content M19291MRA – December 2019 Cloud Gaming: The Era of Games Streaming Stadia's push to conquer the video game market SAMPLE www.idate.org Laurent MICHAUD – Consultant, Media & Telecoms Unit Project leader Laurent joined IDATE DigiWorld in 2000. Laurent is in charge of all market reports on the gaming industry and more generally, those devoted to digital entertainment. His area of expertise covers technological innovation, market analysis, business strategies, strategic marketing, industry planning, networking, event organisation, coaching… Laurent is Chairman of the Haut-de-France video game fund. He is also a lecturer for IDATE DigiWorld, specialising in video game economics and industrial strategies for multimedia products. He is the co-founder and a member of Push Start, the cluster for video game professionals and future professionals in Occitania. Laurent is also an advisor for the EdTech & Entertainment thematic network for Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole French Tech.. Enlighten your digital future! © IDATE DigiWorld 2019 – p. 2 Cloud Gaming: The Era of Games Streaming Stadia's push to conquer the video game market Contents Tables & Figures 1. Video game streaming 4 > Video game streaming . 1.1. From cloud gaming to Stadia 5 Structure of cloud computing services 9 . 1.2. A technology that renders gaming platforms obsolete 6 . The cloud gaming value chain 11 . 1.3. Cloud gaming challenges 7 . Cloud gaming technology 13 . 1.4. Sony, the cloud gaming leader with over 700,000 subscribers 8 . 1.5. Cloud computing and video games: a natural convergence 9 > Market outlook . 1.6. Saas, PaaS, IaaS: more dematerialised services used for gaming 10 .