The Stanford Campus: Its Place in History by Paul V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N S E T 2 I N S E

S AN M AT EO DR M R BRYANT ST D A Y L RAMONA ST TASSO ST W E URBAN LN HERMOSA WY O R O U MELVILLE AV D A L L N Y NeuroscienceQUARRY RD A L-19 1 2 3 B 4 5 6 7 8 Health Center 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 COWPER WAVERLEY ST Hoover Sheraton PALO RD N Neuroscience Hoover KELLOGG AV SANTA RITA AV L Pavilion Hotel VIA PUEBLOWilliam R. Serra Pavilion Shriram Center BRYANT ST D Health Center Hewlett EL CAMINO REAL EVERETT HIGH ST Downtown Grove SERRA MALL R Bioengineering & U (see INSET 1 Garage Teaching L-83 W A O Sequoia LYTTON AVE Palo Alto Westin Chemical Engineering SpilkerHIGH ST E H Center B RAMONA ST at upper left) L EMERSON ST S A C Hotel Hall Stanford A Engineering Math T Vi R SEQ EMBARCADERO RD E EMERSON ST Stanford P R Shopping O Margaret Palo Alto at Palo Alto Arboretum WELLS AVE & Applied Varian CornerJordan A S Courtyard A ALMA ST T Center I Train Station & Children's Sciences Physics (380) (420) Jacks C AVE The Clement V McClatchy O Center (460) W PEAR LN Transit Center Stanford Hotel (120) Wallenberg P HAMILTON AVE Physics & E HERMOSA WY MacArthur Shopping Bank of PARKING ANDR CIRCULATION MAP Marguerite ALMA ST America Palo Astrophysics Memorial (160) S Park Center L-22 Jen-Hsun History T Shuttle Stop Bike route to Alto Y2E2 EAST-WEST AXIS 100 2017-18 Menlo Park Medical Huang 370 110 Court 170 Corner L-87 FOREST AVE Bike Bridge CLARK WY Engineering Ctr. -

Hatfield Aerial Surveys Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt609nf5sn Online items available Guide to the Hatfield Aerial Surveys photographs Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Hatfield Aerial PC0086 1 Surveys photographs Overview Call Number: PC0086 Creator: Hatfield Aerial Photographers Title: Hatfield Aerial Surveys photographs Dates: 1947-1979 Physical Description: 3 Linear feet (43 items) Summary: This collection consists of aerial photographs of the Stanford University campus and lands taken by Hatfield Aerial Surveys, a firmed owned by Adrian R. Hatfield. The images date from 1947 to 1979 and are of two sizes: 18 by 22 inches and 20 by 24 inches. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Information about Access Open for research. Scope and Contents note This collection consists of aerial photographs of the Stanford University campus and lands taken by Hatfield Aerial Surveys, a firmed owned by Adrian R. Hatfield. The images date from 1947 to 1979 and are of two sizes: 18 by 22 inches and 20 by 24 inches. Access Terms Hatfield Aerial Photographers Aerial Photographs Box 1 AP4 Stanford campus, from Faculty housing area before Shopping Center and Medical Center built; Old Roble still standing, Stern under construction; ca. 1947 Box 1 AP5 Main academic campus, ca. -

Stanford University, Press, Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7z09s4v3 No online items Guide to the Stanford University, Press, Photographs Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Stanford University, PC0093 1 Press, Photographs Overview Call Number: PC0093 Creator: Stanford University. Press. Title: Stanford University, Press, photographs Dates: 1924-1976 Bulk Dates: 1924-1945 Physical Description: 2.25 Linear feet Summary: Collection includes photographs, 1936-1945, and one scrapbook, 1924-1976. Subjects of the photographs are the Stanford University Press and staff; Stanford University buildings, students, and faculty/staff; and San Francisco's skyline and bay bridge. Of note among the Stanford photographs are scenes of army training during World War II, the 1942 commencement, the Flying Indians (student flying club), class and laboratory scenes, and a radio workshop ca. 1940. Individuals include John Borsdamm, Will Friend, Herbert Hoover, Marchmont Schwartz, Clark Shaughnessy, Graham Stuart, and Ray Lyman Wilbur. The album pertains largely to staff in the press bindery and includes photographs, clippings, letters, notes, humorous pencil sketches, and poems, mostly by Carlton L. Whitten. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Administrative transfer from the Stanford University Press, 2000. -

Stanford University: a World-Class Legacy

California’s Stanford University: A World-Class Legacy Author’s Note: This article “California’s Stanford University: A World-Class Legacy” is also a chapter in my travel guidebook/ebook Northern California Travel: The Best Options. That book is available in English as a book/ebook and also as an ebookin Chinese. Parallel coverage on Northern California occurs in my latest travel guidebook/ebook Northern California History Travel Adventures: 35 Suggested Trips. All my travel guidebooks/ebooks on California can be seen on myAmazon Author Page. By Lee Foster On October 1, 1891, Senator Leland Stanford and his wife, Jane, officially opened Leland Stanford Junior University. The school became one of the premier institutions of higher education and loveliest campuses in the West. For today’s traveler, headed for the San Francisco region in Northern California, Stanford University is a cultural enrichment to consider including in a trip. The University owes its existence to a tragic death while the Stanford family was on a European Trip in Florence, Italy. After typhoid fever took their only child, a 15- year-old son, the Stanfords decided to turn their 8,200-acre stock farm into the Leland Stanford Junior University. They expressed their desire with the phrase that “the children of California may be our children.” Years later the cerebral establishment is still called by some “The Farm.” Leland Stanford had used the grounds to raise prize trotter racehorses, orchard crops, and wine grapes. The early faculty built homes in Palo Alto, one neighborhood of which became “Professorville.” In a full day of exploration you can visit the campus, adjacent Palo Alto, and the nearby Palo Alto Baylands marshes of San Francisco Bay, a delight to the naturalist. -

Inside Her Intellectual Home from the Director’S Desk Greetings from John Raisian Page 2

talk OF THE tower A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE HOOVER INSTITUTION, STANFORD UNIVERSITY Fall 2011 Hoover Institution welcomes Senior Fellow Amy Zegart Award-winning author and national security affairs expert Amy Zegart calls her Hoover appointment a return to inside her intellectual home From the director’s desk Greetings from John Raisian Page 2 In the Exhibition Pavilion Commemorating the hundred by Amy Hellman Courtesy of The Strauss Center years since the Chinese revolution Page 2 Google “Amy Zegart” and it’s easy her MA and PhD in political science, brings her full circle. What they’re reading, to see why Hoover sought her out At Hoover, she will take her place alongside the same what they’re writing Recommended reading from to join its distinguished cadre of Hoover scholars who advised her as part of her dissertation our fellows fellows. She’s a leading expert on the committee: David Brady, Stephen Krasner, Terry Moe, Page 3 organizational deficiencies of national and Condoleezza Rice. Stanford also holds personal Meet the class of 2011 security agencies—one of the significance: it was here that she met the law student who Get to know the newest members of the Board of Overseers nation’s ten most influential experts in would become her husband. Page 4 intelligence reform. She has served on Amy views the move to Hoover as a return to her the National Security Council, testified Splendor in the glass intellectual home, one that allows her to be part of a Our Bradley Prize winners treat before the US Congress, provided guests to a stirring day in Napa vibrant community and recharge her intellectual batteries. -

Stanford University Slide Collection PC0213

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84q81qv No online items Guide to the Stanford University Slide Collection PC0213 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives April 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Stanford University PC0213 1 Slide Collection PC0213 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stanford University Slide Collection source: Case, Kit Identifier/Call Number: PC0213 Physical Description: .25 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1949-1950 Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 48 hours in advance. For more information on paging collections, see the department's website: http://library.stanford.edu/spc. Conditions Governing Access Materials are open for research use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Conditions Governing Use All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. -

CAMPUS DRIVE EAST Avery Field House Center Deguerre Aquatic Stauffer I Frances Courts Athletics LASUEN ST Center B

Wilkes SWEET Bashford OLIVE WY Legend STANFORD Nordstrom Stanford B of A Visitor Information Shopping Crate & Barrel Center VINEYARD LANE ARBORETUM RD Palo Alto Medical Foundation UNIVERSITY Andronico’s Bus Pick-up/Drop-off Point Psychiatry Town and Country 770 Bike route to Menlo750 Park Bike Bridge Shopping Center Bus Parking 730 VISITOR 780 Stanford Barn 700 WELCH RD Angel of Arboretum Blood Grief Grove Visitor Parking 800 Center EMBARCADERO RD QUARRY RD INFORMATION 777 To (US 101) Ear HWY 82 EL CAMINO REAL 701 Palo Alto Pedestrian Lane Inst. Lucile 703 Sleep High School MAP 900 Packard Ctr Mausoleum 1000 Children’s Hospital T S El Camino at Stanford Grove SAND 1100HILL RD900 Blake Z Heliport Cactus Wilbur LASUEN ST E O Garden NF RD Clinic Parking Falk A S Struct. 3 Lasuen V T T Stanford West Apartments & Knowledge Beginnings Child Development Center Center S A Grove L D CLARK I HomeTel Welch Plaza U Bike route to WY Stanford A Toyon Foster M Hospital Grove Field Palo Alto/Bryant St. S G C A M P U PASTEUR DRIVE Emergency BLAKE WILBUR DR DRIVE G.A. Richards Parking Press Box B Struct. 4 Old NELSON RD Maloney Stanford Athletics Lucas Clinic Anatomy LOMITA DR Galvez Ticket Field Sand Hill Fields Ctr./MSLS Field Cantor Center Office SAM MACDONALD MALL QUARRY EXTENSION for PALM DRIVE CHURCHHILL AVE Parking Park & A Health Res. Struct. 1 Visual Art Visitor Varsity Bus Parking MUSEUM WAY MASTERS MALL & Policy Ctr. for School of Parking Ride Lot Lot Masters WELCH1215 RD (Redwd) Clinical MEDICALMedicine LANE Rodin OAK RD Park & Grove Anatomy Sciences NORTH-SOUTH AXIS Sculpture Ride Lot Research Beckman Chemical Biology Garden CHURCHILL MALL Park & Med School Bud Klein CBRL (CCSR) Center Fairchild Lorry Lokey PAC 10 Steuber Family Ride Lot Office Bldg Cobb Track & Chuck Plaza Aud. -

Stanford University Photographs

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt529036v6 Online items available Guide to the Stanford University Photographs Daniel Hartwig Stanford University. Libraries.Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2015 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Stanford University PC0064 1 Photographs Overview Call Number: PC0064 Creator: Stanford University Title: Stanford University photographs Dates: 1941 Physical Description: 0.25 Linear feet (15 photographs) Summary: Images include the student union, Memorial Church, the inner Quad, the Library, the Stadium, Hoover House, the Stanford Mausoleum, and Hoover Tower. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Information about Access This collection is open for research. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/pubserv/permissions.html. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. -

Palo Alto — California Where Silicon Valley Shops

PALO ALTO — CALIFORNIA WHERE SILICON VALLEY SHOPS Established more than 100 years ago, Palo Alto is now known as the creative and cultural hotbed for technology. A charming mix of historic Northern California culture and cutting–edge innovation, the city offers an exceptional quality of life to its more than 67,000 residents. HP, Tesla, Lockheed Martin, Pinterest and Skype are all centrally headquartered in Palo Alto with other prominent tech companies Google, Facebook, Yahoo and Symantec based in neighboring Silicon Valley communities. Palo Alto is home to Stanford University, one of the top universities and research centers in the country, along with the acclaimed The Stanford University Medical Center and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. VIEW FROM PAVILION 4 AND LADY ELLEN COURT HIGH TECH. HIGH CULTURE. Palo Alto’s natural beauty, together with the sophistication and diversity of its inhabitants, enrich the city’s culture. The population is highly educated, with nearly 80% of residents with college degrees and 50% with a master’s degree or higher. Stanford University serves as a hub for the area’s cultural activity with the Hoover Tower, Memorial Church, The Cantor Arts Center and the Rodin Sculpture Garden all located on the university grounds. Surrounded by gorgeous foothills and a multitude of well-kept city parks, Palo Alto outdoor offerings are endless with renowned hiking trails, golf courses and gardens. Neiman Marcus, Nordstrom, Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s plus more than 140 world-class specialty shops and restaurants An open-air -

Thursday, October 24

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 24 AT A GLANCE 1:30–2:30 pm Bing Concert Hall* (continued) Bing Concert Hall (B-8), capacity: 30 10:00 am–7:00 pm Check-in Campus Walking Tour* Stanford Visitor Center (B-9), 11:15 am–1:00 pm Class Welcome Lunch unlimited capacity 1:30–2:30 pm Classes Without Quizzes and Tours Cantor Arts Center 3:00–3:45 pm Stanford Live Student Performance Cantor Arts Center (B-6), Showcase main lobby, capacity: 40 3:30–4:30 pm Classes Without Quizzes and Tours Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis 4:00–6:00 pm Symposium of Undergraduate Main Quad, Building 160 (D-6/7), Research and Public Service Wallenberg Hall lobby, capacity: 40 5:15–6:30 pm Volunteer Reception David Rumsey Map Center 6:30–9:30 pm Evening on the Quad at Green Library* Green Library (D/E-7), Bing Wing entrance, capacity: 60 10:00 am–7:00 pm Check-in Horses at the Stanford Red Barn Ford Center (D-8/9) Bing Concert Hall on Lasuen Street (B-8), capacity: 40. Bus boarding begins at 11:15 am–1:00 pm Class Welcome Lunch 1:15 pm; tour ends at 3:00 pm Class Headquarters Tent The New Roble Gym and Makerspace 09 04 99 94 89 84 Roble Gym (E-4), entrance on Santa Teresa Street, capacity: 40 79 74 69 64 59 54 Virtual Human Interaction Lab Main Quad, Building 120 (D-6/7), front entrance, capacity: 18 11:15 am–1:00 pm 60th Reunion Ladies’ and Men’s Luncheons 59 3:00–3:45 pm Stanford Live Student See your class events insert Performance Showcase for details. -

2016 International Institutes: Activities and Field Trips

Pre-Collegiate International Institutes 2016 INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTES: ACTIVITIES AND FIELD TRIPS Academic Field Trips: Computer History Museum The Computer History Museum is dedicated to preserving and presenting the stories and artifacts of the information age, and exploring the computing revolution and its impact on society. Find out why computer history is 2000 years old. Learn about computer history´s game-changers in our multimedia exhibitions. Play a game of Pong or Spacewar! Listen to computer pioneers tell their story from their own perspective. Discover the roots of today´s Internet and mobile devices. See over 1,100 historic artifacts, including some of the very first computers from the 1940s and 1950s. Singularity University/Moffett Field Singularity University is a Silicon Valley think tank, organized as a benefit corporation, located at the former Moffett Field. Moffett Field is home to Hangar One, one of the world's largest freestanding structures, covering 8 acres. The massive hangar has long been one of the most recognizable landmarks of California's Silicon Valley. An early example of mid-century modern architecture, it was built in the 1930s as a naval airship hangar for the dirigible USS Macon. In 2015, Google contracted with NASA to take over maintenance of the aging hangars and airfield and it is now regularly used by Google for private and corporate jet travel. Singularity provides educational programs, innovative partnerships and a startup accelerator to help individuals, businesses, institutions, investors, NGOs and governments understand cutting-edge technologies, and how to utilize these technologies to positively impact billions of people. At Singularity, you will hear a presentation from Pascal Finette, who heads up the Startup Program at Singularity University where he grows startups tackling the world’s most intractable problems leveraging exponential technologies. -

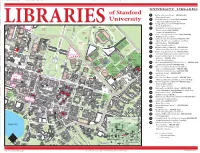

Librariesof Stanford University

C O W P E EL CAMINO REAL R S T CLARK WY Nordstrom Crate & Barrel ARBORETUM RD Knowledge Bike route to1 SAND HILL RD ENCINA AVE Menlo Park Beginnings Andronico's Psychiatry Bike Bridge Child Town DURAND WY Development VINEYARD LN PALM DR Center and 2 770 Country 750 Village UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 730 WAVERLEY ST 780 700 Angel of Freidenrich LCH RD Stanford Grief Center, WE To US 101 Under 800 Barn Construction ARBORETUM RD Arboretum of Stanford 1 Archive of Recorded Sound—650/723-9312 777 EMBARCADERO RD MELVILLE AV Grove Braun Music Center 801 QUARRY RD Palo Alto Lucile Mausoleum High School 2 Art and Architecture Library—650/723-3408 900 OHNS Packard Stanford BRYANT ST Clinic Children’s GALVEZ ST University Cummings Art Building, Main Floor EL CAMINO REAL Advanced Lucile Hospital, KELLOGG AV Medicine Packard Under 3 Biology Library (Falconer)—650/723-1528 Center Construction Eucalyptus Children's T 900 S Grove Herrin Hall, Third Floor (Cancer Center) Ticket Hospital Blake PALM DR at Stanford Cactus N Booth 4 ChemistryCHURCHILL and Chemical AV Engineering LIBRARIESWilbur Lasuen E Garden U Stanford El Camino Clinic Heliport Grove Library (Swain)—650/723-9237 Falk S Stadium Grove C A Center L Toyon Organic Chemistry Building Welch Plaza Parking Stanford Grove COLERIDGE AV A Struct. 3 Hospital 5 Classics Library (Lionel Pearson)**—650/723-0479 B Foster MARIPOSA AV Emergency Building 110, Second Floor R Field D Parking BLAKE WILBUR DR S Stanford 6 EarthCASTILLEJA Scien AVces Library (Branner)—650/723-2746 PASTEUR DR U Old Stadium LOWELL AV Struct.