Download the Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvia Officinalis L.), Petras R

286 Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 104 (2002) 286–292 Donata Bandoniene· a, Antioxidative activity of sage (Salvia officinalis L.), Petras R. Venskutonisa, Dainora Gruzdiene· a, savory (Satureja hortensis L.) and borage Michael Murkovicb (Borago officinalis L.) extracts in rapeseed oil The antioxidant activity (AA) of acetone oleoresins (AcO) and deodorised acetone a Department of Food extracts (DAE) of sage (Salvia officinalis L.), savory (Satureja hortensis L.) and borage Technology, Kaunas (Borago officinalis L.) were tested in refined, bleached and deodorised rapeseed oil University of Technology, applying the Schaal Oven Test and weight gain methods at 80 °C and the Rancimat Kaunas, Lithuania method at 120 °C. The additives (0.1 wt-%) of plant extracts stabilised rapeseed oil b Department of Food efficiently against its autoxidation; their effect was higher than that of the synthetic Chemistry and Technology, antioxidant butylated hydroxytoluene (0.02%). AcO and DAE obtained from the same Graz University of Technology, Graz, Austria herbal material extracted a different AA. The activity of sage and borage DAE was lower than that of AcO obtained from the same herb, whereas the AA of savory DAE was higher than that of savory AcO. The effect of the extracts on the oil oxidation rate measured by the Rancimat method was less significant. In that case higher concen- trations (0.5 wt-%) of sage and savory AcO were needed to achieve a more distinct oil stabilisation. Keywords: Antioxidant activity, sage, savory, borage, acetone oleoresin, deodorised acetone extract, rapeseed oil. 1 Introduction foods is a promising alternative to synthetic antioxidants [8]. Natural products isolated from spices and herbs can Lipid oxidation is a major cause for the deterioration of fat- act as antioxidants either solely or synergistically in mix- containing food. -

Savory Guide

The Herb Society of America's Essential Guide to Savory 2015 Herb of the Year 1 Introduction As with previous publications of The Herb Society of America's Essential Guides we have developed The Herb Society of America's Essential The Herb Society Guide to Savory in order to promote the knowledge, of America is use, and delight of herbs - the Society's mission. We hope that this guide will be a starting point for studies dedicated to the of savory and that you will develop an understanding and appreciation of what we, the editors, deem to be an knowledge, use underutilized herb in our modern times. and delight of In starting to put this guide together we first had to ask ourselves what it would cover. Unlike dill, herbs through horseradish, or rosemary, savory is not one distinct species. It is a general term that covers mainly the educational genus Satureja, but as time and botanists have fractured the many plants that have been called programs, savories, the title now refers to multiple genera. As research and some of the most important savories still belong to the genus Satureja our main focus will be on those plants, sharing the but we will also include some of their close cousins. The more the merrier! experience of its Savories are very historical plants and have long been utilized in their native regions of southern members with the Europe, western Asia, and parts of North America. It community. is our hope that all members of The Herb Society of America who don't already grow and use savories will grow at least one of them in the year 2015 and try cooking with it. -

YIELD and QUALITY of the SUMMER SAVORY HERB (Satureia Hortensis L.) GROWN for a BUNCH HARVEST

ISSN 1644-0692 www.acta.media.pl Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus, 14(3) 2015, 141-156 YIELD AND QUALITY OF THE SUMMER SAVORY HERB (Satureia hortensis L.) GROWN FOR A BUNCH HARVEST Katarzyna Dzida1, Grażyna Zawiślak1, Renata Nurzyńska-Wierdak1, Zenia Michałojć1, Zbigniew Jarosz1, Karolina Pitura1, Katarzyna Karczmarz2 1Lublin University of Life Sciences 2The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin Abstract. The quality of fresh herbs used mainly as food products, is dependent on a number of factors, including the agronomic and environmental ones. The pharmacopoe- ial material of summer savory is the whole or ground herb, which besides essential oil, contains many other biologically active compounds, such as tannins, carotenoids, flavon- oids, and minerals. The aim of the study was to evaluate the yielding of summer savory intended for bunches harvest and mineral composition of the raw material depending on the sowing time and harvesting time. The savory seeds were sown directly into the field on two dates: 23 April and 7 May 2010–2011. The raw material was collected twice: on 1 July and 16 August. Both the first sowing date and the first harvest date affected most preferably the yield of fresh savory herb. Biological value of the ground herb was high and depended on the time of plant harvest. Significantly the greatest content of L-ascorbic acid (39.60 mg 100 g-1 FW), chlorophyll a + b (88.25 mg 100 g-1 FW), carotenoids (26.15 mg 100 g-1 FW), and essential oil (1.79 ml 100 g-1) was found at plants from the first harvest. -

Spice Basics

SSpicepice BasicsBasics AAllspicellspice Allspice has a pleasantly warm, fragrant aroma. The name refl ects the pungent taste, which resembles a peppery compound of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg or mace. Good with eggplant, most fruit, pumpkins and other squashes, sweet potatoes and other root vegetables. Combines well with chili, cloves, coriander, garlic, ginger, mace, mustard, pepper, rosemary and thyme. AAnisenise The aroma and taste of the seeds are sweet, licorice like, warm, and fruity, but Indian anise can have the same fragrant, sweet, licorice notes, with mild peppery undertones. The seeds are more subtly fl avored than fennel or star anise. Good with apples, chestnuts, fi gs, fi sh and seafood, nuts, pumpkin and root vegetables. Combines well with allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, fennel, garlic, nutmeg, pepper and star anise. BBasilasil Sweet basil has a complex sweet, spicy aroma with notes of clove and anise. The fl avor is warming, peppery and clove-like with underlying mint and anise tones. Essential to pesto and pistou. Good with corn, cream cheese, eggplant, eggs, lemon, mozzarella, cheese, olives, pasta, peas, pizza, potatoes, rice, tomatoes, white beans and zucchini. Combines well with capers, chives, cilantro, garlic, marjoram, oregano, mint, parsley, rosemary and thyme. BBayay LLeafeaf Bay has a sweet, balsamic aroma with notes of nutmeg and camphor and a cooling astringency. Fresh leaves are slightly bitter, but the bitterness fades if you keep them for a day or two. Fully dried leaves have a potent fl avor and are best when dried only recently. Good with beef, chestnuts, chicken, citrus fruits, fi sh, game, lamb, lentils, rice, tomatoes, white beans. -

Garden Thyme

Garden Thyme Monthly Newsletter of the East Central Alabama Master Gardeners Association April, 2015 Musings from Jack … My book recommendation this month is The Power of Movement in Plants by Charles Darwin. Fertilize tree fruit and nut Fire ant mound bait that has worked for us. Follow directions. Amdro Bait – active ingredient hydramethylnon Hanging jug traps are catching a lot of fruit flies The peach growers we talked to all say peaches are labor (require frequent spraying) intensive Bag your fruit and give us a report. We used hosiery last year. Dismal failure. Tom and Elaine said paper worked well. There is a UNC website that has an 1895 article for a leveling frame to terrace/contour a hillside. Jack Gardening … Wow!! March 23rd Ann Hammond, Linda Barnes, Martha Burnett and Jack and Sheila Bolen arrived in Cullman for the 25th AMGA Annual Conference. It was three days of garden talk, door prizes, presentations on many different topics and lots of good ‘ole fellowship and food. We all had our favorite speakers but my favorite was Carol Reese who basically said “just get out there and do it – you may change it later but get out and do it!” She was a down-home southern girl with quite the southern drawl and had a message that can cross the lines of all our gardens, landscapes and lives. We attended a session presented by Fred Spicer, Executive Director and CEO of Birmingham Botanical Gardens on “Pruning Techniques, Outcomes and Design Influences” and found his talk very informative and educational. Of course, we don’t have any shrubs to prune but found the information and pictures of his projects from beginning to end very informative. -

Growing Herbs in Laramie County

Catherine Wissner UW Extension Service Laramie County Cheyenne, Wyoming What they offer: planting information, ancient history and lore, poetry, musings, photography, illustrations, recipes, chemical constituents and medicinal virtues of herbs. From the botanical viewpoint, an herb is a seed plant that does not produce a woody stem like a tree. But an herb will live long enough to develop flowers and seeds. Richters catalog out of Canada, list over 200 herbs, 43 different types of Basil, 40 mints, 15 Rosemary’s, 35 Sages, and 10 Beebalms. Seed Savers Exchange lists over 350 herbs. So many choices so little time….. Known as the mint family. Comprising about 210 genera and some 3,500 species. The plants are frequently aromatic in all parts include many widely used culinary, such as: Basil, Mint, Rosemary, Sage, Savory, Marjoram, Oregano, Thyme, Lavender. Mostly with opposite leaves, when crushed the foliage usually emitting various, mostly pleasant odors. Stems usually square. Flowers usually abundant and quite attractive, the sepals and corollas variously united. Calyx 2-lipped or not. Corollas strongly 2-lipped (labiate, hence the family name). Herbs fit into one or more classifications according to use - - culinary, aromatic, ornamental, and medicinal. Culinary herbs are probably the most useful to herb gardeners, having a wide range of uses in cooking. Strong herbs -- winter savory, rosemary, sage. Herbs for accent -- sweet basil, dill, mint, sweet marjoram, tarragon, thyme. Herbs for blending -- chives, parsley, summer savory.. Aromatic herbs Most have pleasant smelling flowers or foliage. Oils from aromatic herbs can also be used to produce perfumes and various scents. -

Use of Essential Oils As Natural Food Preservatives: Effect on the Growth of Salmonella Enteritidis in Liquid Whole Eggs Stored Under Abuse Refrigerated Conditions

Journal of Food Research; Vol. 2, No. 3; 2013 ISSN 1927-0887 E-ISSN 1927-0895 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Use of Essential Oils as Natural Food Preservatives: Effect on the Growth of Salmonella Enteritidis in Liquid Whole Eggs Stored Under Abuse Refrigerated Conditions Djamel Djenane1, Javier Yangüela2, Pedro Roncalés2 & Mohammed Aider3,4 1 Faculty of Biological Sciences and Agronomical Sciences, Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, University Mouloud Mammeri, BP, Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria 2 Department of Producción Animal y Ciencia de los Alimentos (Animal Production and Food Sciences), University of Zaragoza, C/ Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain 3 Department of Soil Sciences and Agri-Food Engineering, Université Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada 4 Institute of Nutrition and Functional Foods (INAF), Université Laval, Quebec, QC, Canada Correspondence: Mohammed Aider, Department of Food Engineering, Laval University, Quebec, QC G1V0A6, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 5, 2013 Accepted: April 25, 2013 Online Published: May 14, 2013 doi:10.5539/jfr.v2n3p65 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v2n3p65 Abstract The steam distillation-extracted essential oils (EOs) of three aromatic plants from the Kabylie region of Algeria (Eucalyptus globulus, Lavandula angustifolia, and Satureja hortensis) were analyzed by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC/MS). The primary compounds from these EOs were 1,8-cineole (81.70%) for Eucalyptus globulus, 1,8-cineole (37.80%) and -caryophyllene (20.90%) for Lavandula angustifolia, and carvacrol (46.10%), p-cymene (12.04%), and -terpinene (11.43%) for Satureja hortensis. To test the antibacterial properties of the EOs, agar diffusion and microdilution methods were used for Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis CECT 4300. -

Herb Chart.Qxp

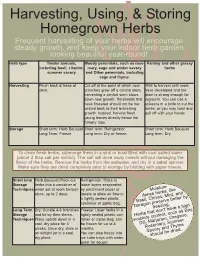

Harvesting, Using, & Storing Homegrown Herbs Frequent harvesting of your herbs will encourage steady growth, and keep your indoor herb garden looking beautiful year-round! Herb type Tender annuals, Woody perennials, such as rose- Parsley and other grassy including basil, cilantro, mary, sage and winter savory herbs summer savory and Other perennials, including sage and thyme. Harvesting Pinch back at base of Cut off at the point at which new Wait to harvest until roots stem. branches grow off a central stem; have developed and the harvesting a central stem slows plant is strong enough for down new growth. Perennials that regrowth. You can use a have flowered should not be har- scissors or a knife to cut the vested back to their branching herbs, or you may twist and growth. Instead, harvest fresh pull off with your hands. young leaves directly below the flowery tops. Storage Short term: Herb Bouquet Short term: Refrigerator. Short term: Herb Bouquet Long Term: Freeze Long term: Dry or freeze. Long term: Dry To clean fresh herbs, submerge them in a sink or bowl filled with cool salted water (about 2 tbsp salt per sinkful). The salt will drive away insects without damaging the flavor of the herbs. Remove the herbs from the saltwater, and dry in a salad spinner. Make sure they are dried completely prior to storage by blotting with paper towels. Short term Herb Bouquet:Place cut Refrigerator: Stack in Storage herbs into a container of loose layers sesparated Techniques water set at room temper- by parchment paper or Moisture ature, up to 2 days. -

SAVORY HERB GARDEN ADDITIONS Lois Sutton the Herb Society of America, South Texas Unit

www.natureswayresources.com SAVORY HERB GARDEN ADDITIONS Lois Sutton The Herb Society of America, South Texas Unit Winter and summer savory are good additions to the late spring garden. They are culinary herbs, providing an oregano-like flavor. Like all herbs give them good drainage and a minimum of six sun-hours. Winter savory (Satureja montana) is a perennial. It looks a bit like thyme: low growing; small dark- green leathery leaves; woody stems. Winter savory's advantage over thyme is that it is more tolerant of summer heat and rains. Its flavor is more pungent than summer savory. In my garden, plant height is consistently about 12" and none have bloomed. Harvest by tip pinching or taking short cuttings. Consistent harvesting does encourage lateral stem development and a bushier plant, but changes in plant shape seem rather minimal. Buy a plant or take cuttings from a friend. Like other herbal perennials it could be planted at any time but avoid the middle of Houston's summer. Set it out on days you like to work in the garden! Summer savory (S. hortensis) is an annual. It is a short plant, like winter savory, but with soft stems and lighter green leaves. It may gift you with small insignificant blooms but I celebrate any herbal blooms! Flowers, leaves and soft stems are all edible. Harvesting frequently will keep this plant a bit more 'organized' looking - it grows quickly and even though it is a short plant, it looks leggy. Summer savory may be grown from seed. Sow with only a light soil cover as the seeds require light for germination. -

Making a Mint with Herbs Is Not All That Difficult by James A

Making a Mint With Herbs Is Not All That Difficult By James A. Duke Herbs are easy to grow, and increasingly easier to selL Cautious growers can supplement their incomes selling herbs, or grow a variety of herbs for home use including cooking and herb teas, or decoration. With a 6- to 7-month growing season, you can grow several perennial herbs that sell well at summer garden stands. My son made vacation spending money by selling herbs at an urban farmer's market. Thyme and chives were his biggest sellers. He started both from seed in pots and marketpacks in our small greenhouse. The chives in 4 x 6 inch peat market- packs sold for over a dollar, planted (at least 5 marketpacks) from a 35i seed package. Other herbs, including thyme, can be subdivided readily by cutting or root divisions. Chives, thyme, and other herbs are ready sellers, weekend after weekend. There is a big demand both for hanging pots and for herbs. Put the two together and you should have a money earner. Balm, corsican mint, orégano, peppermint, rosemary, savory, spearmint, and thyme have good hanging possibilities. Perennials more than annuals tend to drape themselves over the edges of pots, making them especially attractive for macramé plant hangers. Annuals like basil are less attractive to the macramé buyer, but still attractive to the adventurous cook. All can sell. Some buyers are more drawn to the decorative piece of art (pot plus plant) than to pot or plant alone. Some people will buy a hanging rosemary to look at, not to use. -

Summer Savory Satureja Hortensis 5 Ml PRODUCT INFORMATION PAGE

Summer Savory Satureja hortensis 5 mL PRODUCT INFORMATION PAGE PRODUCT DESCRIPTION Throughout ancient Egypt, the dried summer savory herb was powdered and used in various ways. Today, it is common to find this peppery and piney herb in cuisines worldwide. The inventive uses of summer savory throughout the world make it a diverse and powerful plant. Chemically similar to Oregano, Summer Savory essential oil has a warm, herbaceous aroma, making it the perfect addition to herbal and tonic blends. This essential oil is high in antioxidants and carvacrol content, which make it extremely beneficial when used internally. Due to its high phenol content, caution should be taken when inhaling or diffusing Summer Savory. When applied to the skin, Summer Savory should be diluted at a 1:10 ratio with a carrier oil. USES Food Application: Plant Part: Plant • Add one drop to large dishes for a flavorful twist. Extraction Method: Steam distillation • ·Dip toothpick in bottle and stir into meals during Aromatic Description: Spicy, herbaceous preparation for a light flavor addition. Main Chemical Components: Carvacrol, Household γ-terpinene • Diffuse for a calming aroma. DIRECTIONS FOR USE Summer Savory Diffusion: Use one to two drops in the diffuser of choice. Satureja hortensis 5 mL Internal use: Dilute one drop in 4 fl. oz. of liquid. Topical use: Dilute 1 drop essential oil to 10 drops carrier oil. CAUTIONS Possible skin sensitivity. Keep out of reach of children. If you are pregnant, nursing, or under a doctor’s care, consult your physician. Avoid contact with eyes, inner ears, face, and sensitive areas. -

Culinary Herbs * X (Hybrid); Var

Culinary Herbs * x (hybrid); var. (variety); f. (form) G. (Group) ssp. (subspecies) # Botanical Name * Cultivar Common Name Description/Uses Allium ampeloprasum var. ampeloprasum elephant garlic mild, large cloves Allium tuberosum garlic chives garnish for delicate onion Allium schoenoprasum chives like flavor cheese, eggs, cucumbers, Anethum graveolens 'Fernleaf' dill potatoes cheese, eggs, cucumbers, Anethum graveolens 'Long Island Mammoth' dill potatoes sharp tasting root used as a Armoracia rusticana horseradish condiment leaves are smoother, glossier, darker and more Artemisia dracunculus 'Sativa' French tarragon pungent and aromatic than those of the Russian plants. Tagetes lucida Mexican tarragon vegs, meats Chenopodium bonus- Good-King-Henry; poor henricus man's spinach leaves cook like spinach Coriandrum sativum cilantro salads & cooked dishes perennial thistle, leaves & Cynara cardunculus cardoon stems are consumed, not flowers anise flavored seeds & Foeniculum vulgare fennel leaves sweet bay laurel; bay Laurus nobilis leaf; bay laurel soups, stews celery substitute, salads, Levisticum officinale lovage soups infuse the leaves in oil, vinegar or water (for tea); Mentha suaveolens 'Variegata' pineapple mint mint sauce; with chocolate for a dessert tea; salads; condiment in Mentha spicata spearmint curry dishes tea; sauces with chicken or Monarda fistulosa 'Blaustrumpf' bergamot pork Italian, Mediterranean, & Ocimum basilicm sweet basil Thai flavor Italian oregano or hardy similar to sweet marjoram, Origanum x marjoricum marjoram