Terrys Creek Waterways Maintenance & Rehabilitation Masterplan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sewage Treatment System Impact Monitoring Program

Sewage Treatment System Impact Monitoring Program Volume 1 Data Report 2019-20 Commercial-in-Confidence Sydney Water 1 Smith Street, Parramatta, NSW Australia 2150 PO Box 399 Parramatta NSW 2124 Report version: STSIMP Data Report 2019-20 Volume 1 final © Sydney Water 2020 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those listed requires permission from Sydney Water. Sewage Treatment System Impact Monitoring Program | Vol 1 Data Report 2019-20 Page | i Executive summary Background Sydney Water operates 23 wastewater treatment systems and each system has an Environment Protection Licence (EPL) regulated by the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA). Each EPL specifies the minimum performance standards and monitoring that is required. The Sewage Treatment System Impact Monitoring Program (STSIMP) commenced in 2008 to satisfy condition M5.1a of our EPLs. The results are reported to the NSW EPA every year. The STSIMP aims to monitor the environment within Sydney Water’s area of operations to determine general trends in water quality over time, monitor Sydney Water’s performance and to determine where Sydney Water’s contribution to water quality may pose a risk to environmental ecosystems and human health. The format and content of 2019-20 Data Report predominantly follows four earlier reports (2015-16 to 2018-19). Sydney Water’s overall approach to monitoring (design and method) is consistent with the Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council (ANZECC 2000 and ANZG 2018) guidelines. -

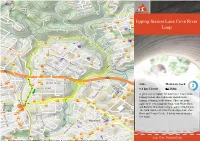

Epping Station Lane Cove River Loop

Epping Station Lane Cove River Loop 3 hrs Moderate track 3 8.4 km Circuit 168m A great way to explore the Lane Cove Valley from Epping Station, this walk loops around North Epping, returning to the station. There are many sights to be seen along this walk, with Whale Rock and Brown's Waterhole being a couple of highlights. The walk explores Devlins Creek, upper Lane Cove River and Terry's Creek. A lovely way to spend a few hours. 94m 30m Lane Cove National Park Maps, text & images are copyright wildwalks.com | Thanks to OSM, NASA and others for data used to generate some map layers. Big Ducky Waterhole Before You walk Grade The servicetrail loops around the top of the Big Ducky waterhole Bushwalking is fun and a wonderful way to enjoy our natural places. This walk has been graded using the AS 2156.1-2001. The overall and there is a nice rock overhang in which to break. Is also a popular Sometimes things go bad, with a bit of planning you can increase grade of the walk is dertermined by the highest classification along bird watching area. Unfortunately, recently there has been large your chance of having an ejoyable and safer walk. the whole track. quantities of rubbish in the area. (If going down to the waterhole Before setting off on your walk check please consider carrying out some of the rubbish if every walker carrys out a bit it will make a difference) 1) Weather Forecast (BOM Metropolitan District) 3 Grade 3/6 2) Fire Dangers (Greater Sydney Region, unknown) Moderate track 3) Park Alerts (Lane Cove National Park) Whale Rock 4) Research the walk to check your party has the skills, fitness and Length 8.4 km Circuit This is a large boulder that looks eerily like a whale, complete with equipment required eye socket. -

Wallumetta June 2019

Wallumetta The Newsletter of Ryde-Hunters Hill Flora and Fauna Preservation Society Inc. JUNE 2019 - No. 275 PRESIDENT’S NOTE The future jobs are in the zero emissions global economy. The outcome of the recent Federal election may be seen as the result of the conflict between the environment and jobs. The Coalition gained 23 of the 30 seats in Queensland and it looks like they will have a total 77 seats in the new Parliament and the ALP 68 with six independents. The major issue in the seats won by the Coalition in Queensland is the level of unemployment and the Adani coal mining project held out the prospect of more jobs for Queensland. The Coalition expressed support for coal mining. However, Professor Ross Garnaut, in the last of six recent lectures on Climate Change discussed “Australia - The superpower of the zero emissions global economy” (www.rossgarnaut.com.au). Ross Garnaut is an economist whose career has been built around the analysis of and practice of policy connected to development, economics and international relations in Australia, Asia and the Pacific. This includes being principal economic adviser to the Prime Minister Bob Hawke, producing the Garnaut Climate Change Review in 2008 and appointment as independent expert to the Multy-Party Climate Change Committee in 2010. In his lecture Ross Garnaut discusses the decline of the coal industry and the opportunities arising for Australia in a global economy which is moving towards zero emissions. Garnaut sets out the industries where Australia, because of its natural and other characteristics will have a competitive advantage. -

LOCATION TIME 2 Nd Week of Month BUSHCARE

BUSHCARE GROUP LOCATION TIME 1 st Week of Month Little Ray Park Bushcare Ray Park, between Magnolia Ave and Casben Close, CARLINGFORD. Meet in carpark on Plympton Rd. 8.30am-12pm Thurs Bambara Bushcare Bewteen Calool Rd & Midson Rd, BEECROFT. Meet at Ray Park carpark on Plympton Rd. 1-4pm Donald Avenue Coates Bushcare Terrys Creek. Meet behind townhouse complex at 6-8 Donald Ave, EPPING 8.30-11.30am Northmead Bushcare Northmead Reserve. Meet at the end of Watson Place, NORTHMEAD 9-11am Sat Baludarri Bushcare Baludarri Wetlands, Corner of Broughton & Pemberton Street, PARRAMATTA 8.30-11am Bruce Cole Bushcare Bruce Cole Reserve. Meet in reserve near corner of Kindelan Rd and Kilian St, WINSTON HILLS 1-4pm Seville Reserve Bushcare Seville Reserve. Meet at bushcare sign at entrance to reserve on Plymouth Avenue, NORTH ROCKS 8-11am Finlay Avenue Bushcare Beecroft Reserve South. Meet at entrance to reserve between 8 & 12 Finlay Ave, BEECROFT 9am-12pm Sun Lake Parramatta Reserve Bushcare Lake Parramatta Reserve. Meet at rear of 94 North Rocks Road, NORTH ROCKS 9am-12.30pm Mobbs Lane Bushcare Mobbs Lane Reserve off Mobbs Lane, EPPING. Meet in reserve behind houses on Third Ave. 1:30-4:30pm Robin Hood Bushcare Toongabbie Creek. Meet adjacent to 76 Sherwood Street, NORTHMEAD 9-11am 2 nd Week of Month Thurs Bambara Darmanin Bushcare Meet on Pioneer Track behind 1st Rosalea Scout Hall, Plympton Rd, CARLINGFORD 9am-12:30pm Fri Bambara Roselea Bushcare Meet at the reserve entrance between 5 & 6 Nallada Place, BEECROFT 9am-12noon 8-11am every second McCoy Park Bushcare (Parramatta Radio Control Meet at entrance to reserve, end of Tucks Road off Powers Road (north of Toongabbie Creek), SEVEN HILLS - month. -

13 August 150813.Pdf

The ONLY local paper north of Mt Colah letter-box delivered weekly ... covering Hornsby to the Hawkesbury River! Phone:Phone: 0202 94569456 28802880 ThursdayThursday 1313 AugustAugust 20152015 BCC READY FOR A SUMMER OF CRICKET Read story p8 Plus!• It’s All About Food p12-13 • Home Improvements p14-17 • Quarry plans revealed p4 Saturday 5th September at 4pm & 7:30pm Friday 11th September at 7:30pm Friday 25th September at 10:30am Members $17 | Visitors $20 Tickets Only $37 Tickets Only $24 BOOK TICKETS TODAY DOWNLOAD OUR APP it’s FREE! www.hornsbyrsl.com.au Simply search for Hornsby RSL on iTunes (02) 9477 7777 or the Google Play store! 4 High St, Hornsby 2077 GAIN INSTANT ACCESS TO COUPONS, DEALS, *Ticket price inclusive of $2 THE LATEST CLUB INFORMATION & MORE! booking fee CHOOSE YOUR ADVENTURE discoverhornsby.sydney BEROWRA WATERS MOUNTAIN BIKE TRAIL HORNSBY HEIGHTS BAR ISLAND BMX TRACK CHERRYBROOK AND DANGAR ISLAND THORNLEIGH SKATE PARK PENNANT HILLS BROOKLYN CYCLING ROUTE CROSSLANDS RESERVE BLUE GUM WALK LISGAR GARDEN CALLICOMA WALK JAMES PARK MAMBARA WALK FAGAN PARK TERRYS CREEK WALK visit discoverhornsby.sydney Berowra Waters Dawn by Francis Keogh 2 THE BUSH TELEGRAPH WEEKLY BEROWRA RFB WIN FIRE FIGHTING AWARDS Story by Councillor Mick Gallagher ZLWK'XUDOQGDQG.X (A thanks for additional info provided by ULQJJDLUG UHFRJQLVHVWKH James Baird, D/Capt Berowra RFB) FRQWULEXWLRQRIWKHEULJDGH repare, Act, Survive WRWUDLQLQJRILWVPHPEHUV PBerowra Rural Fire Brigade within the brigade and (RFB) has taken out two of the WKH+RUQVE\.XULQJJDL WKUHHDQQXDODZDUGVIRU¿UH¿JKWLQJ -

Table 5-4B: List of Virginia Non-Shellfish NPS TMDL Implementation Planning Projects Through 2019

Table 5-4b: List of Virginia Non-Shellfish NPS TMDL Implementation Planning Projects through 2019 EPA Hydrologic Impairment TMDL IP NAME Approval Impaired Water Unit Cause Year Basin: Atlantic Ocean Coastal Mill Creek, Northampton County NS Mill Creek AO21 Dissolved Oxygen, Mill Creek, Northampton County NS Mill Creek AO21 pH Basin: Albemarle Sound Coastal North Landing Watershed (including Milldam, Middle, West NS West Neck Creek - Middle AS14 Bacteria Neck and Nanney Creeks) North Landing Watershed (including Milldam, Middle, West NS Milldam Creek - Lower AS17 Bacteria Neck and Nanney Creeks) Basin: Big Sandy River Knox Creek and Pawpaw Creek 2013 Knox Creek BS04 Bacteria, 2013 Knox Creek BS04 Sediment 2013 Guess Fork BS05 Bacteria, 2013 Guess Fork BS05 Sediment 2013 Pawpaw Creek BS06 Bacteria, 2013 Pawpaw Creek BS06 Sediment 2013 Knox Creek BS07 Bacteria, 2013 Knox Creek BS07 Sediment Basin: Chesapeake Bay-Small Coastal Piankatank River, Gwynns Island, Milford Haven 2014 Carvers Creek CB10 Bacteria Basin: Chowan River Chowan River Watershed Submitted Nottoway River CU01 Bacteria Submitted Big Hounds Creek CU03 Bacteria Submitted Nottoway River CU04 Bacteria Submitted Carys Creek CU05 Bacteria Submitted Lazaretto Creek CU05 Bacteria Submitted Mallorys Creek CU05 Bacteria Submitted Little Nottoway River CU06 Bacteria Submitted Whetstone Creek CU06 Bacteria Submitted Little Nottoway River CU07 Bacteria Submitted Beaver Pond Creek CU11 Bacteria Submitted Raccoon Creek CU35 Bacteria Three Creek, Mill Swamp, Darden Mill Run 2014 Maclins -

Lane Cove River Coastal Zone Management Plan

A part of BMT in Energy and Environment "Where will our knowledge take you?" Lane Cove River Coastal Zone Management Plan Offices Prepared For: Lane Cove River Estuary Management Committee Brisbane (LCREMC), Hunters Hill Council, Lane Cove Council, Denver City of Ryde, Willoughby Councli Mackay Melbourne Newcastle Perth Prepared By: BMT WBM Pty Ltd (Member of the BMT group of Sydney companies) Vancouver Acknowledgement: LCREMC has prepared this document with financial assistance from the NSW Government through the Office of Environment and Heritage. This document does not necessarily represent the opinion of the NSW Government or the Office of Environment and Heritage. lANE COVE RIVER CZMP FINAL DRAFT DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET BMT WBM Pty Ltd Document : Lane Cove River CZMP FINAL BMT WBM Pty Ltd DRAFT Level 1, 256-258 Norton Street PO Box 194 Project Manager : Reid Butler LEICHHARDT NSW 2040 Australia Client : Lane Cove River Estuary Management Committee, Hunters Tel: +61 2 8987 2900 Hill Council, Lane Cove Council, Fax: +61 2 8987 2999 City of Ryde, Willoughby Council ABN 54 010 830 421 www.bmtwbm.com.au Client Contact: Susan Butler (Lane Cove Council) Client Reference: Lane Cove River CZMP Title : Lane Cove River Coastal Zone Management Plan Author/s : Reid Butler, Smita Jha Synopsis : This report provides a revised management plan for the Lane Cove River Estuary under the requirements of the NSW OEH Coastal Zone Management Planning Guidelines. REVISION/CHECKING HISTORY REVISION DATE OF ISSUE CHECKED BY ISSUED BY NUMBER 0 24/05/2012 SJ -

Eastwood to Thornleigh

Eastwood to Thornleigh 3 hrs 45 mins Hard track 4 10.3 km One way 285m This walk explores Terrys Creek and the Lane Cove National Park. From Eastwood station the track follows Terrys creek past a small waterfall, under the M2, past Browns Water hole and along the Lane Cove river before climbing up to Thornleigh Oval and the train station. There are picnic tables at Browns waterhole, not a bad place for lunch, otherwise there are a few nice creek banks to rest along the way 170m 30m Lane Cove National Park Maps, text & images are copyright wildwalks.com | Thanks to OSM, NASA and others for data used to generate some map layers. Terrys Creek Waterfall Before You walk Grade This is a small waterfall on Terrys Creek, and makes a good spot to Bushwalking is fun and a wonderful way to enjoy our natural places. This walk has been graded using the AS 2156.1-2001. The overall break from the walk. Sometimes things go bad, with a bit of planning you can increase grade of the walk is dertermined by the highest classification along your chance of having an ejoyable and safer walk. the whole track. Browns Waterhole Before setting off on your walk check 1) Weather Forecast (BOM Metropolitan District) Grade 4/6 Browns Waterhole is a wide, shallow section of the Lane Cove 4 Hard track River, downstream of a concrete weir. There is a concrete shared 2) Fire Dangers (Greater Sydney Region, unknown) cycle/footpath crossing over the top of the weir, linking Kissing 3) Park Alerts (Lane Cove National Park, Berowra Valley National Park) Point Road, South Turramurra to Vimiera Rd, Macquarie Park. -

Epping to Thornleigh Third Track Environmental Impact Statement

Epping to Thornleigh Third Track Environmental Impact Statement 14. Surface and groundwater This chapter considers the potential impacts of the ETTT proposal on surface and groundwater including water quality. 14.1 Existing conditions 14.1.1 Surface water and drainage The proposal site is located predominantly within the upstream areas of the Byles and Zig Zag Creek catchments, and downstream of the Upper Devlins Creek catchment. Surface waterways within the vicinity of the proposal site include Devlins Creek, Byles Creek, Zig Zag Creek and a number of smaller unnamed overland flow paths. These creeks are shown on Figure 14.1 except Zig Zag Creek which is located just to the north of the figure extent. The external catchments between Epping Station and Pennant Hills Road generally drain from the western side of the corridor to the eastern side, towards Devlins Creek and Byles Creek. These creeks discharge to the Lane Cove River. North of Pennant Hills Station, the catchment falls from the eastern to the western side towards Zig Zag Creek, which discharges into Berowra Creek. The ETTT proposal would pass through undulating terrain, with Devlins Creek the only major watercourse crossing the corridor. Flooding of the creek is unlikely to impact the existing rail corridor, as the creek is located more than 20 metres below the corridor level. No works are proposed in Devlins Creek. There are currently 19 drainage culverts which convey surface water across the railway corridor. Due to the construction of the third track, 14 of these culverts would be required to be extended. 14.1.2 Surface water quality Water quality monitoring is undertaken at a number of locations within the Hornsby LGA, and the results are provided in Council’s Annual Water Quality Report. -

Playgrounds Community Facilities Parks and Recreation Cycleways and Roads Dog Parks

11 09 07 STRONGER 25 01 1515 17 066 COMMUNITIES 08 14 26 28 044 FUND MAP 35 PLAYGROUNDS 1 Lynbrae Ave Park, Beecroft Epping 2 Irving St Reserve, Parramatta Winston Hills 3 George Kendall Riverside Park District 12 Playground, Ermington 4 Forest Park, Epping Carlingford 5 Pinetree Dr Reserve, Carlingford 6 Pembroke St Reserve, Epping Northmead 19 7 Carmen Drive Reserve, Carlingford 8 Burnside Gollan Reserve, Oatlands North Parramatta 24 10 9 Lindisfarne Crescent Reserve, North Rocks 10 34 10 David Hamilton Reserve, Eastwood Wentworthville 30 11 Rainbow Farm Reserve, Carlingford 16 12 McMullen Ave Park, Carlingford 05 13 Dunrossil Park, Carlingford 33 14 Jason Place Reserve, North Rocks 15 Bingara Rd Park, Beecroft Rydalmere 3 16 John Wearne Reserve, Carlingford 03 17 North Rocks Park, Carlingford 18 Blankers-Koen Park, Newington 20 3122 19 Hunts Creek Reserve, Carlingford COMMUNITY FACILITIES 29 Wallawa Reserve Upgrade, Meehan Street, Granville 20 Wentworthville Early Childhood 30 Sommerville Park Upgrade, Eastwood Development Initiative (WECDI) 21 21 Parramatta Artist Studio – Satellite Studios, Rosehill Rydalmere or Silverwater CYCLEWAYS AND ROADS 22 Mobile Active Health, various locations 31 Widening of the bridge at 27 23 Memorial to Indigenous Service Personnel Bridge Road, Westmead 24 North Rocks Park Master Plan 32 Eastern River Foreshore 24 and Upgrade Works, North Rocks Transformation, Rydalmere 32 and Ermington 22 29 022 33 Cycleway infrastructure linking PARKS AND RECREATION Epping with Carlingford 25 Walking Track to Hunts Creek 23 3223 Sydney Waterfall, Carlingford Olympic 26 Sporting Amenity Building at DOG PARKS West Epping Park, Epping 34 Newington Dog Park, Pierre Park 27 All Access Toilet at Ollie Webb De Coubertin Park, Newington 18 Reserve, Parramatta 35 Barnett Park Dog Park Upgrade, All locations are approximate 28 Terrys Creek Rehabilitation, Epping Winston Hills and subject to further 34 community consultation. -

Civil Capabilities

Civil Capabilities DESIGN BUILD MAINTAIN About Us Inside Who we are Our culture and values Our commitment to safety Freyssinet Oceania is a multifaceted contractor Vision The safety of our employees is of paramount importance that provides innovative solutions for specialist civil Freyssinet is constantly innovating and finding new and commitment to safety is at all levels of leadership, engineering, building post-tensioning and structural applications to develop sustainable solutions, making including the highest level. Our safety systems are 2 About Us remediation. The Freyssinet name is synonymous discoveries and filing new patents. reviewed and redesigned daily with new learnings. We with post-tensioning, as Eugène Freyssinet, our are guided by the following principles: Our commitment to the future includes combining Our Civil Services founder, was a major pioneer of prestressed concrete. ˈ We work closely with stakeholders. Innovation is in our DNA. our global expertise with local experience, supporting our clients beyond project handover and developing ˈ We methodically plan our work. As a world leader in soil, structural and nuclear the skills of our employees. ˈ We review our environment regularly. engineering, the Soletanche Freyssinet Group – which ˈ We provide purpose-made equipment. Construction Freyssinet is a part – has an unrivalled reputation and Passion 6 Methodology ˈ We identify and mitigate dangerous situations. expertise in specialised civil engineering. We operate in Our local and global expertise, blended with enthusiasm ˈ We train our people to prevent accidents. more than 100 countries spanning five continents, with and genuine interest in our work, defines who we more than 23,000 employees and a turnover exceeding are. -

8 1 6 5 2 7 7 4 3 10 12 13 14 19 20 19 18 17 16 22 25 23 22 21 24

320000E 321000E 322000E 323000E 324000E 325000E 326000E 327000E 328000E 6267000N e Glade 1 Loretto William Lewis School k Park ree grounds C Burkes Bushland reserves and localities s oup Bush C Adventist land 6266000N ornleigh Turramurra Adventist 1. The Glade and William Lewis Park p98 Granny2 Lane land Browns Lorna Springs Small but valuable remnants of Blue Gum High Forest 6 Field Finlay Reserve True Magnetic ornleigh Cove Pass 2. Granny Springs Reserve p99 Scout Oval National Reserve North North Sheldon Valuable Blue Gum High Forest remnant in the commercial heart of Turramurra Asssociation Park 3. Sheldon Forest and Rofe Park p100 Pennant Hills lease Forest Observatory 6265000N Blue Gum High Forest, forest of shale/sandstone transition, sandstone gully rainforest; fungi, Park 4 3 Twin Creeks terrestrial orchids and a beautiful waterfall B Ludovic o y Reserve Fox Valley 4. Twin Creeks Reserve and Browns Field p106 Blackwood Rofe Lane 5 Memorial Pennant Sc Park Small volcanic diatreme with subtropical rainforest, diverse sandstone ridgetop and valley flora Sanctuary ou Bradley 0 1 2 km Hills ts Creek Pymble 5. Fox Valley p110 Park Cove Reserve Hammond Diverse sandstone ridgetop flora, sheltered Lane Cove River valley with tall forest B Reserve yl Lane C es o 6. Lorna Pass p114 National v e 6264000N Avondale Beecroft R Golf Blackbutt forest and forest of the shale/sandstone transition, gully rainforest, ridgetop heath and Auluba Avondale C 8 iv Course r er woodland eek Park 11 Reserve Dam Ahimsa Whale Bullock 7. Beecroft Reserve and neighbouring reserves p119 Rock 10 STEP Park Tall, open Blackbutt forest makes this a serenely beautiful area despite motorway encroachment Pennant Chilworth k e Track Hills Conservation e Bradley 8.