Getting Organized UNIONIZING HOME-BASED CHILD CARE PROVIDERS 2013 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CWA) Before the US House Committee On

Testimony of Christopher M. Shelton, President, Communications Workers of America (CWA) Before the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means March 27, 2019 “The 2017 Tax Law and Who it left Behind” Thank you Chairman Neal, Ranking Member Brady and Members of the Committee for inviting me to testify today. My name is Christopher Shelton and I am the President of the Communications Workers of America (CWA). CWA represents approximately 700,000 workers in the telecommunications, media, airline, manufacturing, health care and public sectors in the United States, Puerto Rico and Canada. We appreciate having the opportunity to testify today at this hearing on the 2017 tax law because it was one of the most consequential pieces of legislation to be enacted in some time that directly impacts all our members’ lives in many ways, regardless of the sector of the economy they work in. Unfortunately, during the debate and consideration of that legislation there were no hearings or forums where we were given an opportunity to directly share with this Committee or others in Congress our views on how the tax code could be reformed or restructured to benefit working American families. Hearings like this one should have been held before the law was rushed through Congress. So we are deeply grateful Chairman Neal for you and the Committee now giving us an opportunity to share our views on how the new tax law has impacted working Americans’ lives. CWA strongly believes that our tax code needs restructuring and reform and we followed the debate on the tax cut closely. -

Labor and Labor Unions Collection Inventory

Mss. Coll. 86 Labor and Labor Unions Collection Inventory Box 1 Folder 1 Toledo Labor Unions, ca. 1894 (Original) 1. Pamphlet, possibly for multi-union gathering, gives brief history of the following unions: Painters and Decorators’ Union No. 7; Metal Polishers, Buffers and Platers No. 2; Union No. 25, U. B. of C. and J. of A.; Bakers’ union, No. 66; United Association Journeymen Plumbers, Gas Fitters, Steam Fitters, and Steam Fitters’ Helpers, Local Union No. 50; Local Union No. 81 of the A. F. G. W. U.; Toledo Musical Protective Association, Local 25; Beer Drivers’ Union No. 87; Brewery Workers’ Union, No. 60; Drivers and Helpers’ Protective Union, No. 6020; Barbers’ Union No. 5; Toledo Lodge No. 105, I. A. of M.; Amalgamated Council of Building Trades; Toledo Typographical Union, No. 63; Coopers’ Union, No. 34; and Stone Pavers’ Union, No. 5191 Folder 2 Toledo Labor Unions, ca. 1894 (Photocopy) 1. See description of Folder 1 Folder 3 Amalgamated Meat Cutters & Butcher Workmen, Local 466 1. Circular re Kroger and A&P groceries, n.d. Folder 4 American Flint Glass Workers Union, AFL-CIO 1. House organ, American Flint, vol. 68, no. 7 (July 1978) 100th Anniversary – 1878-1978 2. Pamphlet, “American Flint Glass Workers Union, AFL-CIO, Organized July 1, 1878, Toledo, Ohio, ca. 1979 (2 copies) Folder 5 Cigarmakers Int. Union of America, Local Union No. 48 1. Letter to Board of Public Service, Toledo, April 21, 1903 Folder 6 International Association of Machinists, Toledo Lodge No. 105 1. Bylaws, 1943 Folder 7 International Labour Office, Metal Trades Committee 1. -

The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939- 1949

The Role of the Trotskyists in the United Auto Workers, 1939- 1949 Victor G. Devinatz Willie Thompson has acknowledged in his survey of the history of the world- wide left, The Left in History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century Politics, that the Trotskyists "occasionally achieved some marginal industrial influence" in the US trade unions.' However, outside of the Trotskyists' role in the Teamsters Union in Minneapolis and unlike the role of the Communist Party (CP) in the US labor movement that has been well-documented in numerous books and articles, little of a systematic nature has been written about Trotskyist activity in the US trade union movement.' This article's goal is to begin to bridge a gap in the historical record left by other historians of labor and radical movements, by examining the role of the two wings of US Trotskyism, repre- sented by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Workers Party (WP), in the United Auto Workers (UAW) from 1939 to 1949. In spite of these two groups' relatively small numbers within the auto workers' union and although neither the SWP nor the WP was particularly suc- cessful in recruiting auto workers to their organizations, the Trotskyists played an active role in the UAW as leading individuals and activists, and as an organ- ized left presence in opposition to the larger and more powerful CP. In addi- tion, these Trotskyists were able to exert an influence that was significant at times, beyond their small membership with respect to vital issues confronting the UAW. At various times throughout the 1940s, for example, these trade unionists were skillful in mobilizing auto unionists in opposition to both the no- strike pledge during World War 11, and the Taft-Hartley bill in the postwar peri- od. -

U.S. Labor's 1967 Wage Approach

William U.S. LABOR’S 1967 Allan WAGE APPROACH The Detroit correspondent of the US W orker tells of coming struggles on the wages front, and some new features of those struggles. THERE’S A NEW KIND of struggle note sounding off in the ranks of American labor on the eve of negotiations for close to 4,000,000 workers in 1967. “Substantial wage increases” is what you hear, along with no wage freezes; instead, wage re-openers after one year. Warmade inflation and higher profit making are being pointed to in union meetings as new factors in boosting these demands. Negotiating in ’67, will be a million teamsters, a million auto workers, thousands in maritime, railroads, telephone. A million steel workers whose wages are frozen until ’68 are champing at the bit to break loose from that freeze and go get a piece of those steel profits. Half a million workers employed in national, state and city governments, always tied to whatever crumbs politicians will give them, today are walking picket lines, taking strike votes, and are shaking up the city hall, state capitals and Washington. They want at least $2.80 an hour instead of $1.50. United Auto Workers’ Union president, Walter Reuther, always thought to be a pacesetter in labor negotiations, in Long each, California, last June at his union convention told the 3,000 ^legates he favored “an annual salary”. It fell flatter than a Pancake and nowT Reuther is talking of a “substantial wage jttcrease”. He will convene 3,000 delegates from his 900 locals April here in Detroit to finalise the 1967 demands. -

United Auto Workers

Correspondence – United Auto Workers Folder Citation: Collection: Records of the 1976 Campaign Committee to Elect Jimmy Carter; Series: Noel Sterrett Subject File; Folder: Correspondence – United Auto Workers; Container 78 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Carter-Mondale%20Campaign_1976.pdf UAW-CAP REGISTER AND VOTE MANUAL A STE STEP PLAN FOR ORGANIZING AND CONDUCTING AN EFFECTIVE REGISTER AND VOTE CAMPAIGN AT THE COMMUNITY LEVEL -- ·-· -- --��-�- N 0 T E S Who Can Do What -- And How In A Campaign There are many opportunities for sim ple but EFF ECTIVE action. Every group has its own members as the primary objective - and through them can reach families, friends, neighbors and the public. Simi larly, every organization should first stir interest am ong its own members -- then am ong the general public through their members. Start the chain reaction with symbols your own people can wear and display ... Distribute buttons, matches, tags Stockers for all automobiles Posters and Stickers for home windows Then , sustain and extend interest through all your other campaign "resources'' .... Remember they include all of the following: At Your Meetings and wherever people meet-- in churches or synagogues, clubs, sports and social events, community meetings, etc.... Arrange special speakers, debates, discussions Make brief reminder announcements Display posters on stage Distribute handbills, tags, buttons, stickerfO, matches, literature CollEct cards pledging to register and vote Display 100 per cent goal and graph of re gistration increase at each meeting. In Your Publicotions and whatever pe ople read: meeting not:lces, organization publications, bulletin boards, mail and advertising. _Editorials, articles and frequer;.t brief reminders using campaign slogans and voting information. -

2020 Peggy Browning Summer Fellows

Educating Law Students on the Rights and Needs of Workers Stay-At-Home Request Program Book Honoring 2020 Peggy Browning Summer Fellows For their achievements on behalf of workers during the pandemic Washington, DC July 2020 LIUNA is Proud to Support the PEGGY BROWNING FUND LABORERS’ INTERNATIONAL UNION OF NORTH AMERICA TERRY O’SULLIVAN ARMAND E. SABITONI General President General Secretary-Treasurer In our 24th year, the Peggy Browning Fund (PBF) pays tribute to our inspiration, Peggy Browning, and to exceptional leaders who have made major contributions to the cause of workers’ rights. Peggy was a very special person – a Member of the National Labor Relations Board; an extraordinary labor lawyer; a skilled ice skater; a hiker; a loving wife and mother; a caring friend and true supporter of the collective bar- gaining process. PBF was established in 1997 by her friends and family to continue her life’s work – helping workers. We thank everyone whose support helped us become the preeminent organization in the country for encouraging and recruiting new lawyers for the labor movement. Our central program is a 10-week summer fellowship in which law students are matched with the needs of a pool of 70 mentoring organizations, including unions, worker centers, and union-side law firms. As everyone is experiencing, 2020 has become a very challenging year for the Peggy Browning Fund and for working people. When everyone received stay-at- home orders in their states due to the pandemic, we had already awarded 91 Summer Fellowships to first and second-year law students. Thanks to a lot of outreach and creativity from PBF staff and our mentors, we’re very happy to report that most of our mentor organizations were able to transition these fellowships to either work from home or another reasonable solution. -

Labor Environmentalism

The United Auto Workers and the Emergence of Labor Environmentalism Andrew D. Van Alstyne Assistant Professor of Sociology Southern Utah University Mailing Address: Southern Utah University History, Sociology & Anthropology Department 351 West University Boulevard, CN 225Q Cedar City, UT 84720 Phone: (435) 586-5453 E-mail: [email protected] Andrew D. Van Alstyne is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Southern Utah University. His research focuses on labor environmentalism, urban environmental governance, and sustainability. 1 Abstract Recent collaboration between labor unions and environmental organizations has sparked significant interest in “blue-green” coalitions. Drawing on archival research, this article explores the United Auto Workers (UAW)'s labor environmentalism in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the union promoted a broad environmental agenda. Eventually the union went as far as incorporating environmental concerns in collective bargaining and calling for an end to the internal combustion engine. These actions are particularly noteworthy because they challenged the union’s economic foundation: the automobile industry. However, as a closer examination of the record shows, there was a significant disjuncture between the union’s international leadership, which pushed a broad vision of labor environmentalism, and its rank-and-file membership, which proved resistant to the issue. By the close of the 1970s, the conjunction of economic pressures and declining power in relation to management led the union to retreat from its environmental actions. Keywords: Labor Environmentalism, Blue-Green Coalitions, United Auto Workers, Environmental Justice, Social unionism, Environmental Movements, Historical Sociology 2 Introduction Over the past two decades, in response to long term declines in the labor movement’s size, power, and influence, unions have increasingly turned to building coalitions with other social movements on issues ranging from immigration reform to the minimum wage to environmental protection (Gleeson, 2013; Tattersall, 2010). -

Labor Notes Conference

JOIN THE CONVERSATION ONLINE THIS WEEKEND... USE #LABORNOTES 8ľ DQĝ ĝĝĝĝĝĝ>DZU ľOQ)8ĝøĖúĀĝôòóúĝþĝ &) ľ!D ORGANIZING IN OPEN-SHOP AMERICA Welcome to the 2018 Labor Notes Conference Just as members were bracing for a kick to the jugular troublemaking wing is growing, if this conference is a from the Supreme Court, meant to decimate public gauge. employee unionism, some of those same public em- ployees, in West Virginia, showed us all how to dodge This weekend, folks will absorb both 101s and ad- the blow. vanced classes on what works and what doesn’t. Here are some opportunities to look out for: It’s that kind of spirit—and strategic sense—that’s brought 2,500 of you to Chicago this year. Introduce yourself to an international guest. Workers from abroad are looking for their U.S. counterparts. Sis- With what we’ve gone through in the last two years, ters and brothers from Japan, Mexico, Colombia, Nige- the temptation is there to huddle in a corner and cry in ria, Poland, Honduras, the U.K., Norway, and a dozen our beer. But Labor Notes Conferences are where we other countries will inspire you. See the complete list of find both the strategies and the inspiration to come out international guests on page 43, note the many work- swinging instead. We’re proud to host teachers from shops where they’ll speak, and come to the reception at West Virginia, Oklahoma, Arizona, and Kentucky 9 p.m. Friday in the Upstairs Foyer. who are this season’s heroes— Choose a track. -

How Does a Strong Union Affect My Family and Me?

How does a strong union affect my family and me? How does a strong union affect my family and me, you ask? This is like asking how the invention of the light bulb has impacted New York City! This question falls very short, because strong unions have impacted every family in our country in one way or another. To start to unpack this topic, we begin by looking two stories from the past, one tragic, and one heroic. The year is 1911, and the setting is a sweat shop located in the top floors of the Asch building near a wealthy Manhattan neighborhood. Nearly 500 workers, mostly teenage girls - immigrants looking for a better life - report to their jobs on a Saturday morning. It is the sixth day of their fifty-two- hour work week. Some use the one working elevator in the building to make their way to the eighth floor, but most take one of two staircases in the building. They work in a room packed with sewing machines, people, and highly flammable materials. Once the workers are busy at their tasks, one of the stairways is closed and locked to prevent them from stealing. The building does even come close to meeting safety standards of the day. The fire escapes are broken, there is no working sprinkler systems, and there is no limit to the number of occupants allowed on each floor. Three elevators are out of order, and the one hose they have access to is rusted and dry rotted. Once the fire starts, there is no hope for the 146 people who perish in the eighth-floor tinder box - one floor too high for the fire trucks’ ladders to reach. -

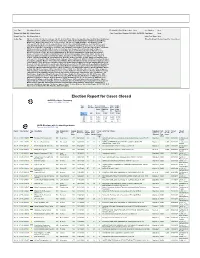

Election Report for Cases Closed

Case Type (All Column Values) Election Held Date Between None - None Case Number None Dispute Unit State (All Column Values) Case Closed Date Between 10/01/2019 - 09/30/2020 Case Name None Dispute Unit City (All Column Values) Labor Org 1 Name None Action Type 10E, 10e, 10j, 10j - 10l, 10j - 10l Contempt, 10k, AC, ALJ, ALJ EAJA, Adversary, Appellate, Appellate Mediation, Bankruptcy, Title of the Report Election Report for Cases Closed Bankruptcy Guidance, Before ALJ, Before ALJ - Compliance, Before Board, Before Board - Compliance, Board Notice, Board Order, Board Order Enforcement, C-Case Decision, CA, CB, CC, CCSLB Compliance Investigation, CCSLB Contempt, CD, CE, CG, CP, Cert Recommendation, Certiorari, Closed w/out Full Compliance, Collection Enforcement, Collection Post-Judgment, Collection Pre-Judgment, Collyer, Complaint, Compliance, Compliance - ALJ, Compliance Agreement, Compliance Determination, Compliance Hrg, Compliance Investigation, Compliance Specification, Compliance ULP Hrg, Conditional, Conditional/Merit, Consent, Contempt, Court Judgment, Court Remand, Court of Appeals Bankruptcy, Court of Appeals Contempt, Decision on Hearing, Decision on Remand, Decision on Review - C Case, Decision on Review - R Case, Decision on Stipulated Facts, Decision on Stipulated Record, Deferral, Discriminatee, Dismissal, District Court, District Crt 10j, District Crt 10l, District Crt Bankruptcy, Dubo, EAJA, EAJA - ALJ, Election Agreement, Enforcement, Enforcement/Review, Ethics, Exceptions or Auto Adopt - C, Exceptions or Auto Adopt - R, Finance, Formal, Formal Bilateral, Formal Settlement, Guideline, Hearing, ILB, ILB - 10j, ILB - Appeal Consideration, ILB - Contempt, ILB - Ct Doc Rev, ILB - Litigation Advice, Informal, Informal Settlement, Initial C, Initial R, Intervention, Interview, Investigative, Litigation Matters - Other, MSJ ? Board Notice, Manual, Merit Dismissal, Mot. to Transfer on StipFacts, Motion ? Other, Motion - Other, Motion for Clarification, Motion for Default Judgment, Motion for Default Judgmnt ALJ, Motion for Reconsid. -

Fr. William P. Leahy, President, Boston College Lee Bollinger

March 14, 2018 To: Fr. William P. Leahy, President, Boston College Lee Bollinger, President, Columbia University Jo Ann Rooney, President, Loyola University Chicago Robert Zimmer, President, University of Chicago Peter Salovey, President, Yale University On behalf of the growing movement of graduate workers, national graduate worker unions and our 4.4 million members, we urge you to honor the critical work of research and teaching assistants at your university and to respect their democratic decision to unionize. American Federation of Teachers, United Auto Workers, UNITE HERE and Service Employees International Union, as well as our graduate worker leaders, are fully committed to working together across our unions to stand with the groundswell of graduate workers demanding a voice on the job through unions. Since August 2016, in elections involving 18,000 research and teaching assistants at thirteen private universities and colleges, graduate workers have voted by a nearly 60 percent overall margin in favor of unionization. At many of the institutions where a majority voted yes, administrators have respected this decision and are now working cooperatively with graduate workers to negotiate agreements and ensure the best outcomes for the university, students and educators. We are deeply disappointed that your administration is not among them. Despite clear votes in favor of unionization at your university, you have attempted to silence graduate workers by using the Trump National Labor Relations Board to rig the system against them. Your refusal to bargain with a democratically-chosen union both ignores the value of RAs and TAs as workers and contradicts the fundamental values for which your university stands. -

(Report Defaults) Election Held Date Between

Report Title Election Report for Cases Closed Region(s) Election Held Date Closed Date (Report Defaults) Between (Report Defaults) and (Report Defaults) Between 10/1/2015 and 9/30/2016 Case Type Case Name Labor Org 1 Name State City (Report Defaults) (All Choices) (All Choices) (Report Defaults) (Report Defaults) Election Report for Cases Closed NLRB Elections - Summary Time run: 10/17/2016 3:48:17 PM Case Type No. of Elections Percent Won by Union Total Employees Eligible to Vote Total Valid Votes for Total Valid Votes Against Total Elections 1496 68.0% 86,145 41,381 27,763 RC 1299 72.0% 73,982 36,716 22,878 RD 172 39.0% 11,086 4,259 4,507 RM 25 32.0% 1,077 406 378 NLRB Elections with 1 Labor Organization Time run: 10/17/2016 3:48:17 PM Region Case Number Case Name Case City State Election Number Valid Votes Labor Org 1 Name Stipulated Certification of Certification Case Closed Type Held Date of Votes for / Consent Representative of Results Closed Reason Eligible Against Labor / Directed Date (Win) Date (Loss) Date Voters Org 1 01, 34 01-RC-145376 LONGWOOD SECURITY RC BOSTON 8/17/2016 59 26 21 United Government Security Stipulated LOSS 8/26/2016 Certification of SERVICES, INC. MA Officers of America International Results Union and Its Local 331 01, 34 01-RC-145728 TRANSIT CONNECTION INC. RC EDGARTOWN 9/10/2015 38 14 17 AMALGAMATED TRANSIT Stipulated WON 3/15/2016 Certific. of MA UNION, LOCAL 1548, a/w Representative AFL-CIO, CLC 01, 34 01-RC-147458 DANAFILMS CORP.