A Directory of Spice Mixes !'2 Notes !&% Select Bibliography !2! Acknowledgements !2&

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spices-Spiced Fruit Bunswithoutpics

More Info On Spices Used in Spiced Fruit Buns CLOVES • Cloves are aromatic, dried flower buds that looks like little wooden nails • it has a very pungent aroma and flavour • It is pressed into oranges when making mulled wine or studded into glazed gammon • believed to be a cure for toothache • should be avoided by people with gastric disorders. NUTMEG • nutmeg fruit is the only tropical fruit that is the source of two different spices: nutmeg and mace • nutmeg is the actual seed of the nutmeg tree, whereas mace is the covering of the seed • nutmeg has a slightly sweeter flavour than mace a more delicate flavour. • It is better to buy whole nutmeg and grate it as and when you need it instead of buying ground nutmeg. • Nutmeg is used in soups, e.g. butternut soup, sauces, potato dishes, vegetable dishes, in baked goods, with egg nog • Used extensively in Indian & Malayian cuisines GINGER • Available in many forms, i.e. fresh, dried, powdered (see image below), pickled ginger, etc. • Powdered ginger is used in many savoury and sweet dishes and for baking traditional favourites such as gingerbread, brandy snaps, ginger beer, ginger ale • Fresh root ginger looks like a knobbly stem. It should be peeled and finely chopped or sliced before use. • Pickled ginger is eaten with sushi. CINNAMON • comes from the inner bark of a tree belonging to the laurel family. • Whole cinnamon is used in fruit compôtes, mulled wines and curries. • Ground cinnamon is used in puddings and desserts such as milk tart, cinnamon buns, to flavour cereal, in hot drinks, etc. -

Tips to Roast Vegetables Spice Guide

Tips to Roast Vegetables • Roast at a high oven temp- 400 to 450 degrees F • Chop vegetables in uniform size so they cook evenly • Don’t over crowd the pan, otherwise they will become soft • Roasting veggies with some oil will help them become crispier • To get the most flavor/crispier roast them on the top rack • Seasoning before putting them in the oven will add flavor • Flip veggies halfway through to ensure even cooking • When roasting multiple types of veggies, ensure they have similar cooking times. Good pairs include: Cauliflower and Broccoli cc Carrots and Broccoli Baby potatoes and Butternut Squash Onions and Bell Peppers Zucchini and Yellow Squash Asparagus and Leeks Spice Guide Table of Contents Spices by Cuisine Herbs and Spices 1 Mexican Coriander, Cumin, oregano, garlic powder, cinnamon, chili powder Herbs and Spices that Pair well with Proteins 2 Caribbean Chicken Fajita Bowl Recipe 3 All spice, nutmeg, garlic powder, cloves, cinnamon, ginger Shelf life of Herbs and Spices 4 French Nutmeg, thyme, garlic powder, rosemary, oregano, Herbs de Provence Spices by Cuisine 5 North African Tips to Roast Vegetables BP Cardamum, cinnamon, cumin, paprika, turmeric, ginger Cajun Cayenne, oregano, paprika, thyme, rosemary, bay leaves, Cajun seasoning Thai Basil, cumin, garlic, ginger, turmeric, cardamum, curry powder Mediterranean Oregano, rosemary, thyme, bay leaves, cardamum, cinnamon, cloves, coriander, basil, ginger Indian Bay leaves, cardamum, cayenne, cinnamon, coriander, cumin, ginger, nutmeg, paprika, turmeric, garam masala, curry powder Middle Eastern Bay leaves, cardamum, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, ginger, coriander, oregano, za’atar, garlic powder 5 Shelf Life of Herbs and Herbs and Spices Spices Herbs Herbs are plants that’s leaves can be used to add flavor to foods. -

Paprika—Capsicum Annuum L.1 James M

HS637 Paprika—Capsicum annuum L.1 James M. Stephens2 Paprika is a type of mild pepper that is dried, ground, and used as a spice. Most of the paprika peppers grown in the United States have been introduced from southern Europe. In areas where grown, selections have been made for color, shape, and thickness of pods, and flavor of the ground product. Some of the local selections have become fairly well established as to type, but none as varieties. Processors have developed varieties for dehydration, but these are not available for public planting. The so-called Hungarian paprika is grown more widely in the United States than any other. Spanish paprika is also grown but to a lesser extent. Figure 1. Paprika pepper. Description Credits: James M. Stephens, UF/IFAS Hungarian paprika produces fruits that are 2–5 inches long, Culture depending on the strain. The shape varies from conical In Florida, very little paprika is grown, although like other (pointed) to oblong (tapering), and walls are usually thin. peppers it appears to be well adapted here and to other Some strains are more pungent (hot) than others, but most pepper-growing areas of the South. Years ago it was grown are mild. There appears to be great variability in the strains commercially in South Carolina and Louisiana. of paprika coming directly from Hungary. Some are much smaller and rounder than the United States selections Paprika is started from seed, early in the spring as soon as already described. frost danger has passed. Plants are spaced 12 inches apart in rows 3 feet apart. -

Download Brochure

Because Flavor is Everything Victoria Taylor’s® Seasonings ~ Jars & Tins Best Sellers Herbes de Provence is far more flavorful than the traditional variety. Smoky Paprika Chipotle is the first seasoning blend in the line with A blend of seven herbs is highlighted with lemon, lavender, and the the distinctive smoky flavor of mesquite. The two spices most famous added punch of garlic. It’s great with chicken, potatoes, and veal. Jar: for their smoky character, chipotle and smoked paprika, work together 00105, Tin: 01505 to deliver satisfying flavor. Great for chicken, tacos, chili, pork, beans & rice, and shrimp. Low Salt. Jar: 00146, Tin: 01546 Toasted Sesame Ginger is perfect for stir fry recipes and flavorful crusts on tuna and salmon steaks. It gets its flavor from 2 varieties of Ginger Citrus for chicken, salmon, and grains combines two of toasted sesame seeds, ginger, garlic, and a hint of red pepper. Low Victoria’s favorite ingredients to deliver the big flavor impact that Salt. Jar: 00140, Tin: 01540 Victoria Gourmet is known for. The warm pungent flavor of ginger and the tart bright taste of citrus notes from orange and lemon combine for Tuscan combines rosemary with toasted sesame, bell pepper, and a delicious taste experience. Low Salt. Jar: 00144, Tin: 01544 garlic. Perfect for pasta dishes and also great on pork, chicken, and veal. Very Low Salt. Jar: 00106. Tin: 01506 Honey Aleppo Pepper gets its flavor character from a truly unique combination of natural honey granules and Aleppo Pepper. On the Sicilian is a favorite for pizza, red sauce, salads, and fish. -

Season with Herbs and Spices

Season with Herbs and Spices Meat, Fish, Poultry, and Eggs ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Beef-Allspice,basil, bay leaf, cardamon, chives, curry, Chicken or Turkey-Allspice, basil, bay leaf, cardamon, garlic, mace, marjoram, dry mustard, nutmeg, onion, cumin, curry, garlic, mace, marjoram, mushrooms, dry oregano, paprika, parsley, pepper, green peppers, sage, mustard, paprika, parsley, pepper, pineapple sauce, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. rosemary, sage, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. Pork-Basil, cardamom, cloves, curry, dill, garlic, mace, Fish-Bay leaf, chives, coriander, curry, dill, garlic, lemon marjoram, dry mustard, oregano, onion, parsley, pepper, juice, mace, marjoram, mushrooms, dry mustard, onion, rosemary, sage, thyme, turmeric. oregano, paprika, parsley, pepper, green peppers, sage, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. Lamb-Basil, curry, dill, garlic, mace, marjoram, mint, Eggs-Basil, chili powder, chives, cumin, curry, mace, onion, oregano, parsley, pepper, rosemary, thyme, marjoram, dry mustard, onion, paprika, parsley, pepper, turmeric. green peppers, rosemary, savory, tarragon, thyme. Veal-Basil, bay leaf, curry, dill, garlic, ginger, mace, marjoram, oregano, paprika, parsley, peaches, pepper, rosemary, sage, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. Vegetables Asparagus-Caraway seed, dry mustard, nutmeg, sesame Broccoli-Oregano, tarragon. seed. Cabbage-Basil, caraway seed, cinnamon,dill, mace, dry Carrots-Chili powder, cinnamon, ginger, mace, marjoram, mustard, -

Summer Vegetable Paella with Saffron & Pickled Pepper Aioli

Summer Vegetable Paella with Saffron & Pickled Pepper Aioli TIME: 50-60 minutes SERVINGS: 2 We’re celebrating the flavors of Spain with tonight’s seasonal paella, a hearty rice dish that originated in the Spanish province of Valencia. Our vegetarian paella features peppers, squash, and green beans—blanched and shocked, then stirred in just before serving to preserve their crisp texture. The rice gets its incredible flavor (and color) from a blend of traditional spices, including aromatic saffron and two kinds of paprika. A bright, creamy aioli is perfect for drizzling. MATCH YOUR BLUE APRON WINE Crisp & Minerally Serve a bottle with this symbol for a great pairing. Ingredients KNICK KNACKS: 1 cup 4 oz 6 oz 2 cloves 2 Tbsps 2 Tbsps 2 Tbsps CARNAROLI RICE SWEET PEPPERS GREEN BEANS GARLIC MAYONNAISE TOMATO PASTE IBERIAN-STYLE SPICE BLEND* 1 1 1 2 Tbsps 1 oz LEMON SUMMER SQUASH YELLOW ONION ROASTED GOLDEN SWEET ALMONDS PIQUANTE PEPPERS * Black Pepper, Spanish Paprika, Smoked Paprika, Rosemary, Dried Oregano, Dried Thyme, & Saffron Download our iOS or Android app, or log in to blueapron.com for how-to videos and supplier stories. 1 1 Prepare the ingredients: F Heat a small pot of salted water to boiling on high. F Wash and dry the fresh produce. F Peel and small dice the onion. F Medium dice the squash. F Cut off and discard the pepper stems. Halve the peppers lengthwise; remove and discard the ribs and seeds. Thinly slice crosswise. F Cut off and discard the stem ends of the green beans. Halve crosswise. -

Periodic Table of Herbs 'N Spices

Periodic Table of Herbs 'N Spices 11HH 1 H 2 HeHe Element Proton Element Symbol Number Chaste Tree Chile (Vitex agnus-castus) (Capsicum frutescens et al.) Hemptree, Agnus Cayenne pepper, Chili castus, Abraham's balm 118Uuo Red pepper 33LiLi 44 Be 5 B B 66 C 7 N 7N 88O O 99 F 1010 Ne Ne Picture Bear’s Garlic Boldo leaves Ceylon Cinnamon Oregano Lime (Allium ursinum) (Peumus boldus) (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) Nutmeg Origanum vulgare Fenugreek Lemon (Citrus aurantifolia) Ramson, Wild garlic Boldina, Baldina Sri Lanka cinnamon (Myristica fragrans) Oregan, Wild marjoram (Trigonella foenum-graecum) (Citrus limon) 11 Na Na 1212 Mg Mg 1313 Al Al 1414 Si Si 1515 P P 16 S S 1717 Cl Cl 1818 Ar Ar Common Name Scientific Name Nasturtium Alternate name(s) Allspice Sichuan Pepper et al. Grains of Paradise (Tropaeolum majus) (Pimenta dioica) (Zanthoxylum spp.) Perilla (Aframomum melegueta) Common nasturtium, Jamaica pepper, Myrtle Anise pepper, Chinese (Perilla frutescens) Guinea grains, Garden nasturtium, Mugwort pepper, Pimento, pepper, Japanese Beefsteak plant, Chinese Savory Cloves Melegueta pepper, Indian cress, Nasturtium (Artemisia vulgaris) Newspice pepper, et al. Basil, Wild sesame (Satureja hortensis) (Syzygium aromaticum) Alligator pepper 1919 K K 20 Ca Ca 2121 Sc Sc 2222 Ti Ti 23 V V 24 Cr Cr 2525 Mn Mn 2626 Fe Fe 2727 Co Co 2828 Ni Ni 29 Cu Cu 3030 Zn Zn 31 Ga Ga 3232 Ge Ge 3333As As 34 Se Se 3535 Br Br 36 Kr Kr Cassia Paprika Caraway (Cinnamomum cassia) Asafetida Coriander Nigella Cumin Gale Borage Kaffir Lime (Capsicum annuum) (Carum carvi) -

Color & Flavor of Paprika

EXPERT TIPS & INFORMATION Why Buy Bulk Spices? ON USING BULK SPICES Want the freshest spices along with the most flexibility and fun while shopping? Then buying in bulk is for you. Comparison shop for a few spices, and you’ll see why bulk is your best choice. Freshness As you measure your spices from the bulk jars, relish the aroma, Cooking color and texture of each. You know that these spices are fresh because the with paprika stock is updated often. They’re bright, not faded, richly aromatic, not faint. You can’t experience the color or aroma of packaged spices before you buy. Paprika contributes its warm, natural color and mild spiciness to a world of dishes. It’s a key ingredient in Hungarian goulash, Versatility chicken paprikash, Indian tandoori chicken and chorizo. Many Whether you’re stocking up on your favorite cooking staples or just buying a pinch of this or that for a particular recipe — when s av v y Portuguese and Turkish recipes also rely upon paprika. spice you buy in bulk, you can always buy the right amount. You don’t While a sprinkling of paprika will brighten the appearance of have to buy an entire package of an exotic spice you’ll use only deviled eggs, to release its flavor it needs heat, preferably moist once a year. And if you want a lot of something — say, enough The heat. That’s why cooks often stir paprika into a little hot oil pickling spice to last through canning season — you don’t have to before adding it to dishes. -

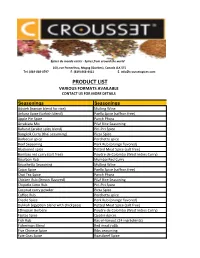

Product List Various Formats Available Contact Us for More Details

Épices du monde entier - Spices from around the world 160, rue Pomerleau, Magog (Quebec), Canada J1X 5T5 Tel. (819-868-0797 F. (819) 868-4411 E. [email protected] PRODUCT LIST VARIOUS FORMATS AVAILABLE CONTACT US FOR MORE DETAILS Seasonings Seasonings Advieh (iranian blend for rice) Mulling Wine Ankara Spice (turkish blend) Paella Spice (saffron free) Apple Pie Spice Panch Phora Arrabiata Mix Pilaf Rice Seasoning Baharat (arabic spicy blend) Piri-Piri Spice Bangkok Curry (thai seasoning) Pizza Spice Barbecue spice Porchetta spice Beef Seasoning Pork Rub (orange flavored) Blackened spice Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Bombay red curry (salt free) Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Bourbon Rub Mumbai Red Curry Bruschetta Seasoning Mulling Wine Cajun Spice Paella Spice (saffron free) Chai Tea Spice Panch Phora Chicken Rub (lemon flavored) Pilaf Rice Seasoning Chipotle-Lime Rub Piri-Piri Spice Coconut curry powder Pizza Spice Coffee Rub Porchetta spice Creole Spice Pork Rub (orange flavored) Dukkah (egyptian blend with chickpeas) Potted Meat Spice (salt free) Ethiopian Berbéré Poudre de Colombo (West Indies Curry) Fajitas Spice Quatre épices Fish Rub Ras-el-hanout (24 ingrédients) Fisherman Blend Red meat ru8b Five Chinese Spice Ribs seasoning Foie Gras Spice Roastbeef Spice Game Herb Salad Seasoning Game Spice Salmon Spice Garam masala Sap House Blend Garam masala balti Satay Spice Garam masala classic (whole spices) Scallop spice (pernod flavor) Garlic pepper Seafood seasoning Gingerbread Spice Seven Japanese Spice Greek Spice Seven -

The Preservative Effects of Natural Herbsspices Used

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL SCIENCE THE PRESERVATIVE EFFECTS OF NATURAL HERBS/SPICES USED IN MEAT PRODUCTS BY YAMOAH ANTHONY GIDEON (B.Sc. Agriculture (Animal Science), Hons) A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN MEAT SCIENCE NOVEMBER, 2016 THE PRESERVATIVE EFFECTS OF NATURAL HERBS/SPICES USED IN MEAT PRODUCTS BY YAMOAH ANTHONY GIDEON (B.Sc. Agriculture (Animal Science), Hons) A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Animal Science, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (Meat Science) Faculty of Agriculture College of Agriculture and Natural Resources NOVEMBER, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this research was carried out by me and that this thesis is entirely my own account of the research. The work has not been submitted to any other University for a degree. However, works of other researchers and authors which served as sources of information were duly acknowledged. YAMOAH ANTHONY GIDEON (PG9005813) ………………...... ……………… (Student Name and ID) Signature Date PROF. OMOJOLA ANDREW BABANTUDE ………………...... ……………… (Meat Science /Food Safety) Signature Date (Supervisor) Certified by: Mr. WORLAH YAWO AKWETEY ………………...... ……………….. (Head of Department) Signature Date ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my mother- Perpetual Annobil, my wife - Mrs. Naomi A. Yamoah and my son - Kant Owusu Ansah. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My greatest thanks go to the Almighty God for His unfailing mercies and favour offered me throughout this programme. "If it had not been the Lord who was on my side, let Israel now say" (Psalm 124:1). -

Grains of Selim) As Additive

DOI: 10.2478/ats-2014-0017 AGRICULTURA TROPICA ET SUBTROPICA, 47/4, 124-130, 2014 Original Research Article Performance, Antimicrobial Effect and Carcass Parameters of Finisher Broilers Given Xylopia aethiopica Dried Fruits (Grains of Selim) as Additive Jonathan Ogagaoghene Isikwenu, Ifeanyi Udeh, Bernard Izuchukwu Oshai, Theresa Ogheneremu Kekeke Department of Animal Science, Delta State University, Asaba Campus, Nigeria Abstract The effect of graded levels of grains of selim on the performance, gut microbial population and carcass characteristics of finisher broilers was investigated. Two hundred and four (204) 28 days old broiler chicks (Marshal breed) were randomly allotted to four treatments with each treatment having three replicates of 17 chicks each in a completely randomized design. Finely blended grains of selim was administered through drinking water on treatments 2, 3 and 4 at concentrations of 0.5, 0.7 and 0.9 g per litre while chicks on treatment 1 (control) received 1.0 g per 1.5 litre of antibiotics (Gendox). Chicks were fed ad libitum with isonitrogenous and isocaloric diets containing 20% crude protein and 3000 Kcal/kg metabolisable energy for four weeks. Results showed no significant (P > 0.05) differences among treatments in the final body weight, total weight gain, daily weight gain, total feed intake, daily feed intake and feed:gain ratio. There were differences in the microbial population of the gastro-intestinal tract with colony count decreasing as the concentration of grains of selim increases. Carcass characteristics and organ weights were similar (P > 0.05) except for thigh and spleen weights, and large intestine lengths where differences (P < 0.05) exist. -

Herbs-Spices-Guide.Pdf

All Seasoning origin origin A mixture of the Mediterranean, India and Mexico India flavour profile All Seasoning flavour profile Basil An all-round seasoning blend including: Basil A classic Mediterranean herb, famous for its delicious aroma and warm Paprika – a slightly earthy flavour with a subtle sweet and peppery taste peppery flavour, it is typically enjoyed with Italian and Mediterranean Black pepper – a spicy, pungent flavour cooking Celery seeds – the dried seeds of celery with a slightly bitter taste Seasoning Herbs serving suggestions serving suggestions • Goes great with vegetables such as courgette, aubergines and carrots Chicken • • Sprinkle over pizzas Meat • • To create sauces for pasta Vegetables • • Mix with olive oil, tomato purée and garlic to make Potatoes • a salad dressing Popcorn • cooking methods & applications cooking methods & applications • Sprinkle onto finished dishes Marinade – mix with a little oil • • Infuse with oil Sprinkle – great for use as an alternative to salt and pepper • • Incorporate into tomato based sauces Rub – works perfectly as a rub for meat and veg • • Blend with nuts, cheese and oil to make pesto products products 99713 – Schwartz All Season 6x840g* 70350 – Everyday Favourites Basil 6x150g* 10016 – Knorr Professional Basil Puree 2x750g* trend alert! trend alert! Healthy Flavour / Fusion 6 7 origin origin Bay LeavesBay Asia America flavour profile Bay Leaves BBQ Seasoning flavour profile Dried Bay Leaves have a pungent, warm aroma, and a less bitter note Most BBQ Seasonings have garlic, onion and paprika then depending than fresh. Bay leaves are one of the principle herbs used on the type of BBQ seasoning it is it will have tomato, pepper, chillies, Seasoning BBQ in Bouquet Garni.