Urban Juvenile Crime in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Across the Geo-political Landscape Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political Networks in the Wartime Era 1937-1949 Guo, Xiangwei Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Across the Geo-political Landscape: Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political -

Business Risk of Crime in China

Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Business and the Ris k of Crime in China Roderic Broadhurst John Bacon-Shone Brigitte Bouhours Thierry Bouhours assisted by Lee Kingwa ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 3 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Business and the risk of crime in China : the 2005-2006 China international crime against business survey / Roderic Broadhurst ... [et al.]. ISBN: 9781921862533 (pbk.) 9781921862540 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Crime--China--21st century--Costs. Commercial crimes--China--21st century--Costs. Other Authors/Contributors: Broadhurst, Roderic G. Dewey Number: 345.510268 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: The gods of wealth enter the home from everywhere, wealth, treasures and peace beckon; designer unknown, 1993; (Landsberger Collection) International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Foreword . vii Lu Jianping Preface . ix Acronyms . xv Introduction . 1 1 . Background . 25 2 . Crime and its Control in China . 43 3 . ICBS Instrument, Methodology and Sample . 79 4 . Common Crimes against Business . 95 5 . Fraud, Bribery, Extortion and Other Crimes against Business . -

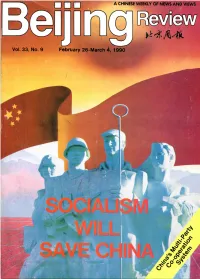

China's NOTES from the EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who with National Culture

—Inspired by the Lei Feng* spirit of serving the people, primary school pupils of Harbin City often do public cleanups on their Sunday holidays despite severe winter temperature below zero 20°C. Photo by Men Suxian * Lei Feng was a squad leader of a Shenyang unit of the People's Liberation Army who died on August 15, 1962 while on duty. His practice of wholeheartedly serving the people in his ordinary post has become an example for all Chinese people, especially youfhs. Beijing««v!r VOL. 33, NO. 9 FEB. 26-MAR. 4, 1990 Carrying Forward the Cultural Heritage CONTENTS • In a January 10 speech. CPC Politburo member Li Ruihuan stressed the importance of promoting China's NOTES FROM THE EDITORS 4 Who's Hurting Who With national culture. Li said this will help strengthen the coun• Sanctions? try's sense of national identity, create the wherewithal to better resist foreign pressures, and reinforce national cohe• EVENTS/TRENDS 5 8 sion (p. 19). Hong Kong Basic Law Finalized Economic Zones Vital to China NPC to Meet in March Sanctions Will Get Nowhere Minister Stresses Inter-Ethnic Unity • Some Western politicians, in defiance of the reahties and Dalai's Threat Seen as Senseless the interests of both China and their own countries, are still Farmers Pin Hopes On Scientific demanding economic sanctions against China. They ignore Farming the fact that sanctions hurt their own interests as well as 194 AIDS Cases Discovered in China's (p. 4). China INTERNATIONAL Upholding the Five Principles of Socialism Will Save China Peaceful Coexistence 9 Mandela's Release: A Wise Step o This is the first instalment of a six-part series contributed Forward 13 by a Chinese student studying in the United States. -

Criminal Punishment in Mainland China: a Study of Some Yunnan Province Documents Hungdah Chiu

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 68 Article 3 Issue 3 September Fall 1977 Criminal Punishment in Mainland China: A Study of Some Yunnan Province Documents Hungdah Chiu Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Hungdah Chiu, Criminal Punishment in Mainland China: A Study of Some Yunnan Province Documents, 68 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 374 (1977) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 68, No. 3 Copyright 0 1977 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. CRIMINAL PUNISHMENT IN MAINLAND CHINA: A STUDY OF SOME YUNNAN PROVINCE DOCUMENTS HUNGDAH CHIU* 4 INTRODUCTION versities. Except for a Canadian hockey team, In an era of information explosion, one of none of the visitors appeared to have acquired the most serious problems for doing research any legal document or law teaching materials is to find enough time to search and to digest in the course of their visits. In the academic voluminous materials. A student of Chinese circle, although a course on Chinese law is law fortunately does not have to face this being offered at six or more American law prob- 5 lem. He does, however, face a more frustrating schools, there have been only a few articles on problem: the lack of sufficient information or post-1966 PRC law and almost none of these research materials concerning legal develop- papers has resorted to recent PRC legal docu- .6 ments in the People's Republic of China (PRC). -

The Peoples Republic of China

Wester Hailes High School The Peoples Republic of China Student Name: Class: S3 Modern Studies Teacher: Mr Sinclair- [email protected] Printed & Digital Edition 2021 Modern Studies CfE Level 4 1 Blooms Taxonomy As well as developing your knowledge, this course will also help to equip you with important skills needed to be successful in Modern Studies and the wider world. The success criteria for each lesson will show you the main skills you will use each period. In Modern Studies we aim to promote Higher Order Thinking Skills which encourage a deeper understanding of the information. The following pyramid shows the different levels of thinking skills and as you work your way up the pyramid your learning will become more complex. This should help you to understand the issues covered more thoroughly. Each lesson the aims will be colour coded corresponding to a level on the pyramid so that you know which skills you are using. Modern Studies and the World of Work As a student of Modern Studies you are learning to understand the world around us as well as the political, social and economic issues that affect our lives. The knowledge you gain from your time in Modern Studies will be with you after school and you will refer back to often and in surprising ways. Skills that we practice will prepare you for the future where you will have to create decisions and justify your actions by analysing and evaluating evidence. Our time is known as the “information age” because we are presented with vast amounts of information on an overwhelming level. -

Sociology and Anthropology in the People's Republic of China

Sociology and Anthropology in the People’s Republic of China Martin Whyte & Burton Pasternak Sociology and anthropology were taught in China as early as 1914 and, by 1949, most major univer sities had established sociology departments. The scope of sociology was broad; it often embraced cultural anthropology, demography, and even social work, in addition to sociology. In a few places anthropology moved toward departmental status in its own right, but the American approach - which attempts to integrate cultural anthropology, linguistics, archaeology, and physical antropology - never really took root in China. This is because the main intellectual inspiration for sociology- anthropology in China came from British social anthropology and from the Chicago school of American sociology. Most priminent scholars did some graduate work abroad, and those who identified with anthropology mainly associated themselves with the British structure-functional tradition (social anthropology). As a result, the line between sociology and anthropology was never a sharp one in China. This is still the case in China today, although the reasons may not be quite the same, as we will see shortly. After 1949 sociology and anthropology fell on hard times. Any science of society of culture that deviated from, or challenged, Marxist-Leninist doctrine was considered a threat - the same atti tude prevailed in Stalin's Russia at the time, where sociology was termed a "bourgeois pseudo science". Chinese sociologists and anthropologists, considered tainted by Western modes of thought, were suspect. In 1952, during the educational re organization campaigns, therefore, sociology was officially proscribed as a discipline; university departments were closed and formal instruction in both sociology and anthropology came to an abrupt 289 end. -

The Rise of Steppe Agriculture

The Rise of Steppe Agriculture The Social and Natural Environment Changes in Hetao (1840s-1940s) Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Yifu Wang aus Taiyuan, V. R. China WS 2017/18 Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Sabine Dabringhaus Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dr. Franz-Josef Brüggemeier Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen und der Philosophischen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Joachim Grage Datum der Disputation: 01. 08. 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures 5 Acknowledgments 1 1. Prologue 3 1.1 Hetao and its modern environmental crisis 3 1.1.1 Geographical and historical context 4 1.1.2 Natural characteristics 6 1.1.3 Beacons of nature: Recent natural disasters in Hetao 11 1.2 Aims and current state of research 18 1.3 Sources and secondary materials 27 2. From Mongol to Manchu: the initial development of steppe agriculture (1300s-1700s) 32 2.1 The Mongolian steppe during the post-Mongol empire era (1300s-1500s) 33 2.1.1 Tuntian and steppe cities in the fourteenth century 33 2.1.2 The political impact on the steppe environment during the North-South confrontation 41 2.2 Manchu-Mongolia relations in the early seventeenth century 48 2.2.1 From a military alliance to an unequal relationship 48 2.2.2 A new management system for Mongolia 51 2.2.3 Divide in order to rule: religion and the Mongolian Policy 59 2.3 The natural environmental impact of the Qing Dynasty's Mongolian policy 65 2.3.1 Agricultural production 67 2.3.2 Wild animals 68 2.3.3 Wild plants of economic value 70 1 2.3.4 Mining 72 2.4 Summary 74 3. -

China Data Supplement January 2007

China Data Supplement January 2007 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 55 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 57 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 62 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 69 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 73 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 January 2007 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member BoD Board of Directors Cdr. Commander CEO Chief Executive Officer Chp. Chairperson COO Chief Operating Officer CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep.Cdr. Deputy Commander Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson Hon.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Just a Scholar: the Memoirs of Zhou Yiliang (1913–2001) Zhou Yiliang in 2001

Just a Scholar: The Memoirs of Zhou Yiliang (1913–2001) Zhou Yiliang in 2001. Private collection. Just a Scholar: The Memoirs of Zhou Yiliang (1913–2001) Translated by Joshua A. Fogel LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 Cover illustration: Zhou Yiliang, Beijing University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zhou, Yiliang, 1913-2001. Just a scholar : the memoirs of Zhou Yiliang (1913-2001) / translated by Joshua A. Fogel. pages cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-25417-6 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26041-2 (e-book) 1. Historians-- China--Biography. I. Fogel, Joshua A., 1950- translator. II. Title. DS734.9.Z468A3 2014 951.05092--dc23 [B] 2013029081 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface. ISBN 978-90-04-25417-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-26041-2 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Order and Law in China

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by George Washington University Law School GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2020 Order and Law in China Donald C. Clarke George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Donald C., "Order and Law in China" (2020). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 1506. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1506 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORDER AND LAW IN CHINA Donald Clarke* Aug. 25, 2020 I. Introduction Does China have a legal system? The question might seem obtuse, even offensive. However one characterizes the institutions of the first thirty years of the People’s Republic, the near half- century of the post-Mao era1 has almost universally been called one of construction of China’s legal system.2 Certainly great changes have taken place in China’s public order and dispute resolution institutions. At the same time, however, other things have changed little or not at all. Most commentary focuses on the changes; this article, by contrast, will look at what has not changed—the important continuities that have persisted for over four decades. These continuities and other important features of China’s institutions of public order and dispute resolution suggest that legality is not the best paradigm for understanding them. -

Devastating Blows Religious Repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang

Human Rights Watch April 2005 Vol. 17, No. 2(C) Devastating Blows Religious Repression of Uighurs in Xinjiang Map 1 .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Map 2 .............................................................................................................................................. 2 I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 3 A note on methodology...........................................................................................................9 II. Background.............................................................................................................................10 The political identity of Xinjiang..........................................................................................11 Uighur Islam ............................................................................................................................12 A history of restiveness..........................................................................................................13 The turning point––unrest in 1990, stricter controls from Beijing.................................14 Post 9/11: labeling Uighurs terrorists..................................................................................16 Literature becomes sabotage.................................................................................................19 -

World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems

WORLD FACTBOOK OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS China by Jianan Guo Ministry of Justice Guo Xiang China University of Politics and Law Wu Zongxian Ministry of Justice of China Xu Zhangrun University of Politics and Law Peng Xiaohui China University of Politics and Law Li Shuangshuang China University of Politics and Law This country report is one of many prepared for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems under Grant No. 90-BJ-CX-0002 from the Bureau of Justice Statistics to the State University of New York at Albany. The project director for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice was Graeme R. Newman, but responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in each report is that of the individual author. The contents of these reports do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the U.S. Department of Justice. GENERAL OVERVIEW i. Political System. China is a unitary, multi-national socialist country with 31 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under authority of the central government. There are also cities and autonomous prefectures operating directly under these provincial and autonomous regional governments, which totaled 458 in 1991. Under these cities and autonomous prefectures are county and city districts, which totaled 1,904 in 1991. China's criminal justice system consists of police, procurates, courts and correctional institutions. At the central level, the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Justice administer China's police and correctional institutions, respectively. The Supreme People's Court is the highest judicial branch in the country.