Volume 4 Number 3, 1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standing up to Peer Pressure, One Song at a Time

TEACHER’S GUIDE OCTOBER 2016 VOL.36 NO.1 WRITING BACHATA LYRICS The Dominican A Practical Music’s Rise to Guide Global Fame LISTENING GUIDE Prince’s NOT FOR “When Doves ALESSIA Cry” DISTRIBUTIONCARA Standing Up to Peer Pressure, NOW One Song at PLAYING a Time The Minimoog Model D INCLUDES LESSON PLANS FOR The Art of the Lyric • How Bachata Got Its Groove • Listening Guide: Prince’s “When Doves Cry” • Song of the Month: “Wild Things” by Alessia Cara This issue supports National Core Arts Standards 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 FROM THE EDITOR Welcome to the 36th season of Music Alive! Beginning with this season, I’ll be following in the foot- October 2016 steps of my esteemed colleague Mac Randall as the new ed- Vol. 36 • No. 1 itor-in-chief of Music Alive! Magazine. As a writer, musician, and part-time music teacher, I’m excited to be in a position CONTENTS of selecting and editing content to be shared with young music students through Music Alive! Music’s value as an educational subject 3 The Art of the Lyric is frequently reported on by the media, but for those of us who are passionate about music education, its importance is common knowledge. Whether or not 4 How Bachata students intend to become professional musicians, we know that their studies Got Its Groove in music will be invaluable to them. As we move forward with Volume 36, we hope to provide you and your 5 Listening Guide: students with content that will not only inspire them but will also challenge Prince’s “When them—whether it’s in understanding a technical aspect of music, wrapping Doves Cry” their minds around the inner workings of the music industry, or opening their ears toNOT the sounds of different FOR cultures and subcultures. -

Session Handout Salsa & Merengue Mash Up

SESSION HANDOUT SALSA & MERENGUE MASH UP Walter Diaz (WALLY) ZIN™ Member, USA SESSION HANDOUT Presenter Walter Diaz (Wally) Schedule 50 min: Theoretical explanation about all these fantastic rhythms and their influences. 70 min: Master Class, including the Warm Up and Cool Down. (Total: 2 hours) Session Objective The session will give ZIN Members valuable information and knowledge about Salsa and Merengue, thus providing participants with the tools to easily identify these rhythms and put them into practice. History & Background HISTORY OF MERENGUE Merengue is a style of music and dance originated in the Caribbean, specifically in the Dominican Republic in the early nineteenth century. Originally, the Merengue was interpreted with stringed instruments (guitars). Years later, the guitars were replaced by the Accordion along with the Guira and the Tambora (drum of two patches), the structure of the whole instrumental típico. This set, with three instruments, represents the synthesis of three cultures that shaped the flavor of the Dominican culture. European influence is represented by the Accordion, the African by the Tambora (drum of two patches), and the aboriginal by the Taino or Güira. Although in some areas of the Dominican Republic, especially in the Cibao, there are still typical sets, this has evolved throughout the twentieth century with the introduction of new instruments like the saxophone and later with the appearance of bands with complex wind sections. The origin of the word merengue goes back to colonial times and comes from the word Muserengue, the name given to dances among some African cultures. The Dominican Merengue genre has played a major role within the environment of Afro Caribbean. -

Dur 07/06/2016

MARTES 7 DE JUNIO DE 2016 3 TÍMPANO Juan Luis Guerra llega a los 59 El cantante latinoamericano festeja su cumpleaños inmerso en trabajo. NOTIMEX Ciudad de México Género Uno de los grandes exponentes de ba- Se le considera el chata y merengue, el cantautor y pro- creador de un ductor dominicano Juan Luis Gue- movimiento musical rra, ganador de tres Grammy y 15 en el merengue Grammy Latinos, llega hoy a los 59 dominicano que hace años de vida con la preparación de que este ritmo ‘Juntos en concierto’, que presentará renazca vestido de el 11 de junio al lado de Chayanne y una lírica impecable, Olga Tañón. imponente e El “show” se llevará a cabo en Pe- impactante, según rú y los reconocidos intérpretes ha- los críticos en la rán un recorrido musical por sus éxi- materia. AGENCIAS tos. En el caso de Guerra, prevé can- tar temas como ‘Bachata rosa’, ‘Oja- ALICIA KEYS LE DICE lá que llueva café’ y ‘Mi bendición’, Inicios entre muchos más. ADIÓS AL MAQUILLAJE La cantante Alicia Keys se sumó al movimiento feminista #NoMa- En 1984 formó su DE LETRAS Y MÚSICA keUp, el cual toma cada vez más fuerte. Keys, de 35 años, difundió grupo 4.40 y grabó su Juan Luis Guerra Seijas, nombre una carta abierta a sus fanáticos en “Lenny Letter”, una web que de- primer álbum completo del cantante, nació el 7 de fiende el #nomakeup, donde confirma su decisión de no volver a usar “Soplando”. Este junio de 1957 en Santo Domingo. El maquillaje y unirse a la tendencia de “al natural”. -

Si Saliera Petróleo”

UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ANDRÉS BELLO FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL MENCIÓN: ARTES AUDIOVISUALES TRABAJO DE GRADO ESCRITURA DEL GUIÓN PARA LARGOMETRAJE MUSICAL “SI SALIERA PETRÓLEO” SIBADA CORIO, Edgar Alberto Tutor: Lic. AMUNDARAÍN, Javier Caracas, mayo de 2014 Formato G: Planilla de evaluación Fecha: _______________ Escuela de Comunicación Social Universidad Católica Andrés Bello En nuestro carácter de Jurado Examinador del Trabajo de Grado titulado: ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Dejamos constancia de que una vez revisado y sometido éste a presentación y evaluación, se le otorga la siguiente calificación: Calificación Final: En números____________ En letras: _______________________ Observaciones__________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Nombre: __________________ __________________ ___________________ Presidente del Jurado Tutor Jurado Firma: __________________ __________________ ___________________ Presidente del Jurado Tutor Jurado Anna María Sanó, gracias por tanto. Esto es para ti. AGRADECIMIENTOS A Dios; gracias por guiarme, -

Our Menu Selection

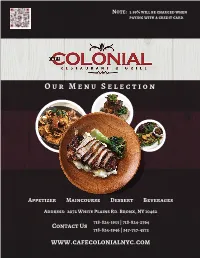

Note: 3.99% will be charged when paying with a credit card. Our Me nu S e l e c t i o n Appetizer Maincourse Dessert Beverages Address: 2072 White Plains Rd. Bronx, NY 10462 718-824-1933 | 718-824-2764 Contact Us 718-824-1946 | 347-737-4572 www.cafecolonialnyc.com PARA EMPEZAR Alitas Caribeñas $10.00 Mofonguitos de Cangrejo $16.00 Chicken wings dipped in our homemade Fresh Crab Meat served over Mini spicy BBQ Sauce, Garlic, and Basil. Mofongo with Creole Sauce. Calamari $12.00 Almejas Casino $16.00 Fried Calamari served with Classic Half a Dozen Baked Little Neck Clams Marinara Sauce. steamed with Fresh Herbs, Onions, Peppers and Bacon. Rollitos de Berenjena $10.00 Sample Plate $16.00 Eggplant stuffed with Fresh Mozzarella & Baked Casino Clams, Shrimp, Calamari Ricotta Cheese in Classic Marinara Sauce. and Eggplant. Camarones Fritos con Coco $11.00 Trio de Tacos $16.00 Deep-fried Shrimp with Coconut Enjoy Chicken, Shrimp and Beef Tacos on breading, served with home style made Corn Tortillas with Jalapeño, Onions, Sauces for dipping Crema Fresca and Tomatillo Salsa Seafood Empanadas $12.00 Pulpo a la Parrilla $22.00 Scrumptious Seafood Empanadas Piquillo Pepper Sauce, Roasted served with Chipotle Mayo. Potatoes, Shallots & Vinaigrette. SALADS Potato Salad $9.00 Grilled Chicken Salad $15.00 Potato Salad with Carrots & Eggs, Grilled Chicken over Lettuce, Mixed with Mayonnaise and Olive Oil. Tomatoes and Cucumbers. Caesar Salad $ 8.00 Shrimp Salad $18.00 Romaine lettuce, Caesar dressing, Mixed Lettuce, Crisp Bacon, Red Peppers, Parmesan Cheese and Croutons. Red Onions and Succulent Grilled Shrimp. -

Entrega Gobernadora Obras Metros Del Canal De Riego Donde O De Su Vida

Nogales, Sonora, México Buenos días AÑO 16 • NÚMERO 6006 Sonora y Arizona 32 PÁGINAS • 4 SECCIONES HOY ES VIERNES 31 $10 pesos • Un dólar en Arizona DE MAYO DE 2019 CON EL PROGRAMA DE VIVIENDA Beneficiarán a mil 400 familias Visita Nogales coordinador de zona de la Comisión Nacional de Vivienda Agustín Valle ciudad visitando casa por casa para Nuevo Día/Nogales, Sonora constatar la necesidad de la gente y que sean beneficiadas con este pro- on más de mil 400 vi- grama. viendas, producto del Destacó el trabajo realizado trabajo conjunto entre la por personal de Desarrollo Social del federación con autorida- Gobierno Municipal, así como la des de estatales y muni- gente desplegada por las colonias cipales, las familias no- de la Comisión de Vivienda del Go- Cgalenses se beneficiarán con una vi- bierno del Estado, todos juntos, por vienda digna que genere identidad un solo fin que es el beneficio de la con una construcción asistida que gente. garantice su duración y queden Con el trabajo que se está ha- atrás materiales reciclados, elimi- ciendo es que se necesita garantizar nando el cartón y las láminas. la posición del terreno, que no sea En entrevista para Grupo Mul- una invasión, despojo, esté en pleito timedios NUEVO DIA, con Raymun- legal o cualquier situación de riesgo. Israel Victoria, acompañado por Alejandro Castro, de Desarrollo Social, en entrevista para Grupo Multimedios NUEVO DIA. do Estrada Charles, Israel Victoria, Victoria dijo que con estos pri- Coordinador de zona de la Comisión meros criterios donde presenten pa- domicilio, CURP, documentos del vez hecha la solicitud se hace la revi- un par de semanas estarán en esta Nacional de Vivienda, de visita en gos de predial, recibos pagos de vi- predio y acta de nacimiento, se pue- sión para determinar si son benefi- frontera los asistentes técnicos para esta frontera, avaló el trabajo de vienda o terrenos, además docu- de elaborar la solicitud. -

Bachata Rosa Album Download Bachata Rosa

bachata rosa album download Bachata Rosa. The follow-up album to Juan Luis Guerra's international breakthrough with Ojalá Que Llueva Café, Bachata Rosa is a milestone effort that spawned seven hit singles, garnered critical acclaim from all corners, and popularized bachata on an international scale. Generally considered Guerra's masterwork, Bachata Rosa is a departure from his previous four albums and sets the template for subsequent efforts with its mix of rousing merengues and romantic bachatas. In the case of Bachata Rosa, each side of the ten-song album opens and closes with an uptempo song, and three of the four are extraordinary ("Rosalia," "A Pedir Su Mano," "La Bilirrubina"). The middle of each five-song album side (and remember that Bachata Rosa was released at a time when there were separate A- and B-sides) is reserved for slow, romantic songs in a bachata style. Five of these six songs were released as singles ("Como Abeja al Panal," "Carta de Amor," "Estrellitas y Duendes," "Burbujas de Amor," "Bachata Rosa"). As some critics have noted, these songs aren't bachatas in a strict sense; rather, they fuse bachata with the bolero and ballad styles in the same way that Guerra's merengues are often fusions of other uptempo tropical styles like soca and salsa. In any event, Guerra is credited with popularizing bachata in the early '90s and rightfully so. Both "Burbujas de Amor" and "Estrellitas y Duendes" reached the Top Five of the Billboard Hot Latin Tracks chart, and Guerra won a Grammy Award for Best Tropical Latin Performance. -

Juan Luis Guerra and the Merengue: Toward a New Dominican National Identity

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Dominican Studies Institute 2013 Juan Luis Guerra and the Merengue: Toward a New Dominican National Identity Raymond Torres-Santos CUNY Dominican Studies Institute How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/dsi_pubs/2 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Research Monograph Juan Luis Guerra and the Merengue: Toward a New Dominican National Identity Raymond Torres-Santos Dominican Studies Research Monograph Series About the Dominican Studies Research Monograph Series The Dominican Research Monograph Series, a publication of the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute, documents scholarly research on the Dominican experience in the United States, the Dominican Republic, and other parts of the world. For the most part, the texts published in the series are the result of research projects sponsored by the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute. About CUNY Dominican Studies Institute Founded in 1992 and housed at The City College of New York, the Dominican Studies Institute of the City University of New York (CUNY DSI) is the nation’s first, university-based research institute devoted to the study of people of Dominican descent in the United States and other parts of the world. CUNY DSI’s mission is to produce and disseminate research and scholarship about Dominicans, and about the Dominican Republic itself. The Institute houses the Dominican Archives and the Dominican Library, the first and only institutions in the United States collecting primary and secondary source material about Dominicans. -

Colombia Creativa 1

Colombia Creativa 1 Colombia Creativa 2 ANÁLISIS DE LA INTERPRETACIÓN DEL BAJO ELÉCTRICO EN EL MERENGUE DOMINICANO DE JUAN LUIS GUERRA, TOMANDO COMO REFERENCIA EL APORTE MÚSICAL DE LOS BAJISTAS: JOE NICOLÁS Y HÉCTOR SANTANA Flavio Antonio Cuta Cristancho UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA NACIONAL FACULTAD DE BELLAS ARTES LICENCIATURA EN MÚSICA BOGOTÁ D.C. 2013 Colombia Creativa 3 ANÁLISIS DE LA INTERPRETACIÓN DEL BAJO ELÉCTRICO EN EL MERENGUE DOMINICANO DE JUAN LUIS GUERRA, TOMANDO COMO REFERENCIA EL APORTE MÚSICAL DE LOS BAJISTAS: JOE NICOLÁS Y HÉCTOR SANTANA Flavio Antonio Cuta Cristancho Código 2011275070 Asesora Metodológica: Clara E. Núñez Asesor Musical: Mauricio Sichacá UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA NACIONAL FACULTAD DE BELLAS ARTES LICENCIATURA EN MÚSICA BOGOTÁ D.C. 2013 Colombia Creativa 4 FORMATO RESUMEN ANALÍTICO EN EDUCACIÓN - RAE Código: FOR020GIB Versión: 01 Fecha de Aprobación: 10-10-2012 Página 1 de 3 1. Información General Tipo de documento Trabajo de Grado de Especialización Acceso al documento Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Biblioteca Central ANÁLISIS DE LA INTERPRETACIÓN DEL BAJO ELÉCTRICO EN EL MERENGUE DOMINICANO DE JUAN Título del documento LUIS GUERRA, TOMANDO COMO REFERENCIA EL APORTE MUSICAL DE LOS BAJISTAS: JOE NICOLÁS Y HÉCTOR SANTANA Autor(es) Flavio Antonio Cuta Director Asesora metodológica: Clara E. Núñez Asesor musical: Mauricio Sichacá Publicación Bogotá. Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, 2014. p. 291 Unidad Patrocinante UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA NACIONAL Bajo eléctrico, Merengue dominicano, Análisis, Ritmo, Palabras Claves Melodía, Armonía, Tambora, Interpretación, Influencia, Aporte musical, Género. 2. Descripción La música al estilo Juan Luis Guerra es el producto de una combinación en la investigación musical como en el aporte del talento de cada uno de los músicos que participaron en las producciones, dejando un gran legado que motiva a la investigación del merengue dominicano. -

Songs by Artist Spanish - Latino Karaoke Title Title Title A

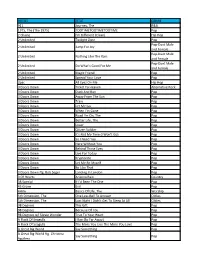

3 Jokers Karaoke Songs by Artist Spanish - Latino Karaoke Title Title Title A. Alvarado Adan's El Compita Alberto Beltran Parranda Jibara Misa De Cuerpo Presente Cuando Vuelvas Comnigo A. Alvarado (Wvocal) Nadie Es Eterno El 19 Parranda Jibara Paloma Negra Enamorado A.B. Quintanilla III & Los Kumbia Kings Que Falta Me Hace Mi Padre Ignoro Tu Existencia Azucar Te Vengo A Ver Papa Boco Boom, Boom Un Sonador Siempre Con Mi Carino Desde Que No Estas Aqui Y Dicen Te Miro A Ti Dime Quien Adolencentes Orquesta Alberto Beltran (Wvocal) Fuiste Mala Ponte Pilas Aunque Me Cueste La Vida Insomnio Adolescentes Orquesta Compasion Ishhh! Anhelos Cuando Vuelvas Comnigo La Cucaracha Persona Ideal El 19 Me Enamore Adriana Ahumada (Marisol) Enamorado Me Estoy Muriendo Estrella Del Rock Ignoro Tu Existencia Mi Gente Akwid Papa Boco No Tengo Dinero Como, Cuando Y Donde Siempre Con Mi Carino Aaron & Su Grupo Ilusion Jamas Imagine Te Miro A Ti Destilando Amor Mi Aficion Alberto Cortez Todo Me Gusta De Ti Si Quieres A Mis Amigos Aaron & Su Grupo Ilusion (Wvocal) Tu Mentira Camina Siempre Adelante Todo Me Gusta De Ti Alacranes Musical Castillos En El Aire ABBA A Cambio De Que Cuando Un Amigo Se Va Chiquitita A Mover El Bote Distancia Dancing Queen Como Pude Enamorarme En Un Rincon Del Alma Fernando Copa Tras Copa Gracias A La Vida Gimme Gimme Gimme Cuenta Pagada Mi Arbol Y Yo I Have A Dream Donde Estas No Soy De Aqui Ni Soy De Alla Take A Chance On Me El Caminante Partir De Manana Voulez Vous El Corral De Piedra Alberto Cortez (Wvocal) Winner Takes It All El Venadito -

View Song List

ARTIST TITLE GENRE 911 Journey, The R&B 1975, The (The 1975) TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME Pop 2 Chainz I'm Different (Clean) Hip Hop 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Pop Pop-Duet Male 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy and Female Pop-Duet Male 2 Unlimited Nothing Like The Rain and Female Pop-Duet Male 2 Unlimited Do What's Good For Me and Female 2 Unlimited Magic Friend Pop 2 Unlimited Spread Your Love Pop 2pac All Eyez On Me Hip Hop 3 Doors Down Ticket To Heaven Alternative Rock 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Pop 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Pop 3 Doors Down Train Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Pop 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Pop 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The Pop 3 Doors Down Better Life, The Pop 3 Doors Down Loser Pop 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier Pop 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Pop 3 Doors Down So I Need You Pop 3 Doors Down Here Without You Pop 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Pop 3 Doors Down Live For Today Pop 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself Pop 3 Doors Down Be Like That Pop 3 Doors Down ftg. Bob Seger Landing In London Pop 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain Country 38 Special If I'd Been The One Pop 45 Grave Evil Pop 4Him Basics Of Life, The Worship 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer Oldies 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All Oldies 98 Degrees This Gift Pop 98 Degrees Because Of You Pop 98 Degrees w/ Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart Pop A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) Pop A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love Pop A Great Big World Say Something Pop A Great Big World ftg. -

El Otro Merengue

CHRISTINA BAKER ——————————————————————————— Migrating Bandas/Banderas Sonoras: Musical Affiliation and Performances of Passing in Indocumentados…el otro merengue Este artículo analiza cómo Indocumentados…el otro merengue, obra teatral de José Luis Ramos Escobar, capta las tensiones que caracterizan a los actos migratorios caribeños y las consiguientes articulaciones identitarias. Ambientada en Nueva York, la obra explora los sentimientos de (no) pertenencia y las diferencias socio-culturales entre puertorriqueños y dominicanos expresados mediante el lenguaje, el racismo y los gustos musicales. El protagonista capta esta complejidad cuando compra los documentos de un puertorriqueño fallecido y deja de ser un dominicano indocumentado, Para examinar estas transformaciones, se utilizarán conceptos teóricos provenientes de los estudios performativos, queer y musicales. Palabras claves: Identidad, música tropical, inmigración indocumentada, teatro y performance caribeño This article analyzes how, Indocumentados…el otro merengue, by José Luis Ramos Escobar, captures the tensions that undergird Caribbean migratory flows alongside articulations of being. Taking place in New York, the theatre piece explores feelings of (not) belonging and socio-cultural divisions between Puerto Ricans and Dominicans via linguistic markers, racism and musical preferences. The protagonist best captures this complex situation when he buys the documents of a deceased Puerto Rican man, leaving his identity as an undocumented Dominican behind in favor of this new self. In order to analyze this transformation, I apply theoretical concepts from Performance Studies, Queer Studies and Musicology. Keywords: Identity, tropical music, undocumented immigration, Caribbean theatre & performance “Yo soy yo” – Gregorio Santa, Indocumentados REVISTA CANADIENSE DE ESTUDIOS HISPÁNICOS 41.3 (PRIMAVERA 2017) 474 The notion that a person simply is who they are, in many ways, is an essentialist and simplistic articulation of identity formation.