A Geography Resource for Australian Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Failing to Conserve Leadbeater's Possum and Its Mountain Ash Forest

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The Australian National University Failing to conserve Leadbeater’s Possum and its Mountain Ash forest habitat David Blair1, David Lindenmayer1 &Lachlan McBurney1 1Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601 Corresponding author: [email protected] The conservation of the Critically Endangered Leadbeater’s Possum Gymnobelideus leadbeateri in Victoria’s Mountain Ash Eucalyptus regnans forests is one of the most controversial native mammal conservation issues in Australia. Much of the controversy results from long-running conflicts between the demands of the native forest logging industry and associated impacts on Leadbeater’s Possum and its Mountain Ash forest habitat. Here we argue that despite a legislative obligation to protect Leadbeater’s Possum and some limited recent improvements in management, conservation efforts for the species have gone backwards over the past decade. The key problems we identify include that the Victorian Government has: (1) maintained levels of wood production that are too high given the amount of the forest estate that was burned in 2009, (2) failed to substitute clearfell logging practices with more ecologically-sensitive Variable Retention Harvesting Systems, (3) ignored the science (including by its own researchers) on the need for a large protected area for Leadbeater’s Possum, (4) altered key definitions such as those for mature trees and old growth that have substantially weakened the ability to protect Leadbeater’s Possum, and (5) overlooked the array of forest values beyond timber production (such as water and tourism) and which make a greater contribution to the economy. -

Submission To: Victorian Bushfire Inquiry

Submission to: Victorian Bushfire Inquiry Addressed to: Tony Pearce; Inspector-General Emergency Management, Victoria Submission from: Emergency Leaders for Climate Action https://emergencyleadersforclimateaction.org.au/ Prepared on behalf of ELCA by: Greg Mullins AO, AFSM; Former Commissioner, Fire & Rescue NSW May 2020 1 About Emergency Leaders for Climate Action Climate change is escalating Australia’s bushfire threat placing life, property, the economy and environment at increasing risk. Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) was formed in April 2019 due to deep shared concerns about the potential of the 2019/20 bushfire season, unequivocal scientific evidence that climate change is the driver of longer, more frequent, more intense and overlapping bushfire seasons, and the failure of successive governments, at all levels, to take credible, urgent action on the basic causal factor: greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of coal, oil and gas. Greenhouse emissions are causing significant warming, in turn worsening the frequency and severity of extreme weather events that exacerbate and drive natural disasters such as bushfires. ELCA originally comprised of 23 former fire and emergency service leaders from every state and territory and every fire service in Australia, from several State Emergency Service agencies, and from several forestry and national parks agencies. At the time of submission, ELCA continues to grow and now comprises 33 members, including two former Directors General of Emergency Management Australia. Cumulatively, ELCA represents about 1,000 years of experience. Key members from Victoria include: • Craig Lapsley PSM: Former Emergency Management Commissioner; Former Fire Services Commissioner; Former Deputy Chief Officer, Country Fire Authority. • Russell Rees AFSM: Former Chief Fire Officer, Country Fire Authority Victoria. -

Gippsland Bushfire Management Strategy 2020

Gippsland Bushfire Management Strategy 2020 Fuel management Bushfire Risk Engagement Areas Prevention of human-caused ignition strategy (pilot) First-attack suppression strategy (pilot) Acknowledgements We acknowledge and respect Victoria’s Traditional Owners as the original custodians of the state’s land and waters, their unique ability to care for Country and deep spiritual connection to it. We honour Elders past and present, whose knowledge and wisdom has ensured the continuation of culture and traditional practices. We are committed to genuinely partner and meaningfully engage with Victoria’s Traditional Owners and Aboriginal communities to support the protection of Country, the maintenance of spiritual and cultural practices and their broader aspirations in the 21st century and beyond. We thank our colleagues and partners in the Gippsland Safer Together Executive Team, Gippsland Regional Strategic Fire Management Planning Committee and Gippsland Strategic Bushfire Management Planning Working Group for their support developing the strategy. We would like to acknowledge all the workshop participants and the agencies who provided staff to attend each session for their contributions to the working group. We would also like to acknowledge those who participated in the Engage Victoria surveys for their comments. Authors Prepared by members of the Gippsland Strategic Bushfire Management Planning Working Group. Analysis was undertaken by the Risk and Evaluation Team, Gippsland. Aboriginal people should be aware that this publication may contain images or names of deceased persons in photographs or printed material. Photo credits Risk and Evaluation Team, Gippsland © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. -

Inside This Edition

Inside this Edition The Presidents Report Pages 2-3 Calendar – Coming Events Page 4 Committee – Officers and Delegates 2015 – 2016 Page 5 Notice of AGM / 2016 Next Wave Page 6 Beginners Day at Buxton in Pictures Page 7 Eucumbene River Report Pages 8-9 Noojee Area Report Pages 10-11 CVFFC Update / VRFish Update Page 12 Fin Clippers at Snobs Creek Pages 13-14 Daylesford Partners & Family Fishing / Exploring Weekend Notice Page 15 Flies / Fly Tying / Wednesday Afternoon Social / Club Caps & Badges Page 16 Casting Page 17 General Meeting Minutes Pages 18-20 Accommodation Offers Page 21 Membership Nomination Form Page 22 Member Contact Details Page 23 Volume 49 June 2016 No 5 The Presidents Report Scott Dargan It looks and feels like winter has arrived which means that we are now heading into closed season and focussing on keeping warm. That is unless you are an avid lake fisherman who does not mind stalking fish in the wide range of lakes that we have available to us across Victoria. Winter is also a good time to start thinking about non fishing activities such as refining your casting technique, checking all your gear and tying a few flies. Remember that Paul Harris runs a casual fly tying session on the third Thursday of each month at the clubrooms from 7.30pm. Also stay tuned for details about our Winter Fly Tying Course that will commence in early August. We once again had great attendance at both our May Members night and General Meeting with our guest speaker Travis Dowling (Director of Fisheries Victoria) drawing a strong crowd. -

Bushfires in Our History, 18512009

Bushfires in Our History, 18512009 Area covered Date Nickname Location Deaths Losses General (hectares) Victoria Portland, Plenty 6 February Black Ranges, Westernport, 12 1 million sheep 5,000,000 1851 Thursday Wimmera, Dandenong 1 February Red Victoria 12 >2000 buildings 260,000 1898 Tuesday South Gippsland These fires raged across Gippsland throughout 14 Feb and into Black Victoria 31 February March, killing Sunday Warburton 1926 61 people & causing much damage to farms, homes and forests Many pine plantations lost; fire New South Wales Dec 1938‐ began in NSW Snowy Mts, Dubbo, 13 Many houses 73,000 Jan 1939 and became a Lugarno, Canberra 72 km fire front in Canberra Fires Victoria widespread Throughout the state from – Noojee, Woods December Point, Omeo, 1300 buildings 13 January 71 1938 Black Friday Warrandyte, Yarra Town of Narbethong 1,520,000 1939 January 1939; Glen, Warburton, destroyed many forests Dromona, Mansfield, and 69 timber Otway & Grampian mills Ranges destroyed Fire burnt on Victoria 22 buildings 34 March 1 a 96 km front Hamilton, South 2 farms 1942 at Yarram, Sth Gippsland 100 sheep Gippsland Thousands 22 Victoria of acres of December 10 Wangaratta grass 1943 country Plant works, 14 Victoria coal mine & January‐ Central & Western 32 700 homes buildings 14 Districts, esp >1,000,000 Huge stock losses destroyed at February Hamilton, Dunkeld, Morwell, 1944 Skipton, Lake Bolac Yallourn ACT 1 Molongolo Valley, Mt 2 houses December Stromlo, Red Hill, 2 40 farm buildings 10,000 1951 Woden Valley, Observatory buildings Tuggeranong, Mugga ©Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, State Government of Victoria, 2011, except where indicated otherwise. -

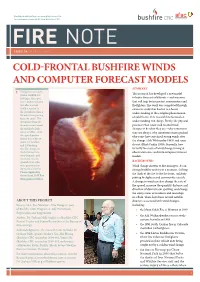

Cold-Frontal Bushfire Winds and Computer Forecast Models

ISSUE 54 MARCH 2010 COld-frONTAL BUSHFIRE WINDS AND COMPUTER FORECAST MODELS SUMMARY This photo was taken This research has developed a new model from a Firebird 303 JetRanger helicopter to better forecast cold fronts – and outcome over Lawloit, Victoria, that will help better protect communities and just after a recent firefighters. The work was completed through wildfire was hit by extensive study that has led to a better the downburst from a understanding of the complex phenomenon thunderstorm passing of cold fronts. This research has focused on by to the south. The downburst from the understanding two things. Firstly, the physical thunderstorm turned processes that cause cold-frontal wind the northerly flank changes to be what they are – why sometimes into a headfire - with they are abrupt, why sometimes more gradual, the typical pattern why some have sustained strong winds after from a line of fire of the change (Ash Wednesday 1983) and some about 5/6 headfire and 1/6 backing do not (Black Friday 1939). Secondly, how fire. The change in to verify forecasts of wind change timing at fire behaviour was observation sites and from computer forecast very dramatic, and models. increased risks to ground crews who BACKGROUND were positioned to Wind change matters to fire managers. It can the north of the fire. change bushfire activity in a moment, shifting Photo supplied by the flank of the fire to the fire front, suddenly Steve Grant, DSE Fire Management Officer. putting firefighters and communities at risk. A change in wind can also change the rate of fire spread, increase the quantity, distance and direction of downstream spotting, and change the safety status of residents and townships in a flash. -

Vicforests' Koala Management

VicForests Instruction Koala Management August 2015 1.0 Copyright © VicForests All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of VicForests. Document Information General Information File Path : J:\VICFORESTS\PUBLIC\SUST. FOREST. MAN. SYSTEM\ FOREST OPERATIONS MANUAL\WRITTEN INSTRUCTIONS\APPROVED\VICFORESTS INSTRUCTION – KOALA MANAGEMENT RecFind Ref: Description: This document outlines VicForests process for managing Koalas Author: C. Powell Creation Date: July 2015 Procedure Owner(s): Conservation Biologist Current Version: 1.0 Copy Number: 1 Review Period: Last review date: 5/08/2015 Next review date: 5/08/2018 Revision History New Version Revision Date Author(s) Old Version Revision Notes Reviewers The following positions should review the instruction prior to any significant amendment being approved General Manager Planning Manager Forest Performance Approval Approver Position / Resolution Date Nathan Trushell General Manager, Planning Signature: Unless stamped ‘CONTROLLED COPY’ in red, all printed copies of this procedure are uncontrolled. The latest version can be found in VicForests SharePoint– Sustainable Forest Management System Version: 1.0 Last Updated: 5/08/15 Procedure Owner: Conservation Biologist Page 2 of 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Purpose .................................................................................................................................... -

Observations on a Nesting Hollow of Yellow- Tailed Black Cockatoo, and the Felled Tree That Hosted It, in North-Eastern Tasmania

59 The Tasmanian Naturalist (2004) 126: 59-63 OBSERVATIONS ON A NESTING HOLLOW OF YELLOW- TAILED BLACK COCKATOO, AND THE FELLED TREE THAT HOSTED IT, IN NORTH-EASTERN TASMANIA Mark Wapstra1 and Niall Doran2 1Forest Practices Board, 30 Patrick Street, Hobart, Tasmania 7000 Email: [email protected] 2Threatened Species Unit, Department of Primary Industries, Water & Environment, GPO Box 44, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 INTRODUCTION The yellow-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus Shaw, 1794) is one of Tasmania’s most familiar birds, its common name aptly describing its distinctive black plumage with yellow undertail. The species is gregarious and is usually seen in family groups or small parties and occasionally congregates in large flocks (Forshaw and Cooper, 1981). In north-eastern Tasmania, large flocks are a familiar sight and sound in areas of extensive softwood plantation. The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is native to Tasmania and is widely distrib- uted throughout the State (Brown and Holdsworth, 1992). It is nomadic and cov- ers large distances in search for food, which comprises seeds, nuts, fruit or ber- ries from a wide range of native trees and shrubs such as eucalypts, banksias, acacias and hakea but also a large range of insects and larvae, and seeds and nuts of introduced flora such as pines. There are few reported observations of breeding behaviour of the yellow- tailed black cockatoo in Tasmania (Brown and Holdsworth, 1992) but the spe- cies is known to use large hollows in over-mature (often dead) eucalypts, in (primarily wet) sclerophyll forests. Haseler and Taylor (1993) provide informa- tion on a nest tree from dry sclerophyll forest in north-eastern Tasmania. -

Eucalyptus Species for Taranaki

Eucalyptus Species for Taranaki 14 Introduction conditions. Especially suited to saline winds. This This information sheet follows on from the information species holds its form, mills extremely well at a young sheet, ‘Eucalyptus’ (No.13), which discusses general age, and is largely unaffected by pests and diseases. management issues such as siting, selecting tree stocks, Eucalyptus nitens shining gum E. nitens is more tolerant planting regimes, silviculture, establishment, weed to wet sites and is suited to planting in all damper sites control, planting technique, fertiliser requirements, and that E. fraxinoides won't tolerate, for example, low lying pest and disease control. damper areas along streambanks and on hillsites affected by springs. It is also equally suited to drier As no one species of eucalypt will thrive over the range 'fraxinoides' sites. Generally, E. nitens is suited to of sites in a similar manner to Pinus radiata, selecting the planting in soils that are a bit damper than pine will most suitable species for a particular site is of critical tolerate. Furthermore, the tree has good form, a fast importance. Species selection is just as important, if not growth rate, and is resistant to cold. It has a good more, than issues associated with their subsequent reputation for milling and exceptional peeling management. properties (better than radiata pine), although more trial work on drying properties is required. E. nitens A lack of objective, accessible, practical local knowledge used to be affected by the paropsis tortoise beetle and experience of eucalypt growing in Taranaki makes (Paropsis charybdis), but since that beetle has been it difficult for people seeking advice on correct species controlled, the species is largely free of pest and disease to plant. -

'The Way He Tells It ...'

‘The way he tells it ...’ Relati onships aft er Black Saturday A research report in four volumes Vol. 1 Executi ve Summary and Recommendati ons Vol. 2 Women and Disasters Literature Review Vol. 3 The Landscape of My Soul — Women’s Accounts Vol. 4 A Gut Feeling — The Workers’ Accounts Narrati ve reinventi on The way you tell it we had an infallible plan your foresight arming us against catastrophe and your eff orts alone prepared our home against calamity The way you tell it your quick thinking saved the day you rescued us and we escaped ahead of the inferno while you remained defi ant Unashamedly you reinvent the narrati ve landscape Your truth is cast yourself in the starring role the shrieking wind paint me with passivity hurled fl ames through the air render me invisible you fl ed, fought and survived fl esh seared mind incinerated You weave a fantasti c tale by which you hope to be judged inside is just self-hatred and in seeking to repair your tatt ered psyche brush me with your loathing I understand, even forgive but this is not the way I tell it Dr Kim Jeff s (The ti tle of this report is adapted from ‘Narrati ve Reinventi on’ with sincere thanks to Dr. Kim Jeff s) Acknowledgements Our heartf elt thanks to the women who shared their experiences, hoping — as we do — to positi vely change the experiences of women in the aft ermath of future disasters. They have survived a bushfi re unprecedented in its ferocity in Australia’s recorded history and each morning, face another day. -

National Recovery Plan for the Barred Galaxias Galaxias Fuscus

National Recovery Plan for the Barred Galaxias Galaxias fuscus Tarmo A. Raadik, Peter S. Fairbrother and Stephen J. Smith Prepared by Tarmo A. Raadik, Peter S. Fairbrother and Stephen J. Smith (Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria). Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, October 2010. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74208-883-9 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities website: www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre telephone 136 186 Citation: Raadik, T.A., Fairbrother, P.S. -

Eucalyptus Species Trials on Pumiceland

Eucalyptus species trials on pumiceland G.R. Johnson and M.D. Wilcox Trial Sites All three trial sites were flat but otherwise varied as follows: ABSTRACT Rotoehu: Warm site, altitude 70 m. Former pasture on a sandy pumice soil. The site was rotary hoed before Twenty species and two hybrids of Eucalyptus were tested being planted in November 1977. on three central North Island pumice/and sites at altitudes of ?Om, 380 m, and 920 m. At age nine years Eucalyptus Waiotapu: Intermediate in temperature, altitude 380 m. A sallgna had performed the best on the warmer low altitude former firebreak on a hydrothermal mud soil site, E. delegatensis and E. dendromorpha had per depleted of topsoil. Planting lines were ripped as a formed well on the high altitude site, and E. regnans was form of soil cultivation before planting in the st on the i'1:termdiate altitude site. For overall adap November 1977. tability on pumice soils E. regnans and E. fastigata were Matea: Cold site, altitude 920 m. Formerly in scrub of the best, but E. delegatensis and E. fraxinoides also did Leptospermum, Dracophyllum, Phyllocladus, and well on more than one site. Eucalyptus nitens showed Hebe. Humic topsoil overlies a yellow pumice at excellent potential on all three sites, notwithstanding its this site. Before planting in December of 1977 the susceptibility to Paropsis attack. area was: crushed (July, 1976), burnt (December, 1976) disced and ripped (May, 1977), and sprayed 'Introduction with atrazine/amitrole and simazine (August, Eucalyptus have been planted in New Zealand for over 100 1977).