Design Research: What Is It? What Is It For?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victor Margolin

VICTOR MARGOLIN 1307 S. Wabash #702 Dept. of Art History Chicago, IL 60605 University of Illinois 935 W. Harrison St Chicago, IL. 60607-7039 tel./312-413-2463 fax/312-413-2460 Education 1979–1981 Union Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio. Ph.D. in Design History. Dissertation: "The Transformation of Vision: Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, and László Moholy-Nagy as Graphic Designers, 1917-1933." 1963–1964 Fulbright Scholar, Institute of Higher Cinema Studies, Paris, France 1959–1963 Columbia University, New York. Bachelor of Arts. Majored in English. Film history and production courses at the Center for Mass Communication Current Position 1982–present University of Illinois at Chicago, History of Architecture and Art Department. Professor of Art and Design History (Department Chair, 1990-1993); Director of Graduate Studies, 2000- 2001 University Honors Fellow of the Institute for the Humanities, 1985 - 1986 Fellow of the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy, 1998--2000 UIC Teaching Recognition Program Award, 1997 Silver Circle Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1991, 1997; nominated three additional times for the award UIC Excellence in Teaching Award, 2000 Featured as Outstanding Teacher in the UIC Annual Report, 2001 University Scholar, 2000-2001 Publications Books Culture is Everywhere: Selections from the Museum of Corntemporary Art (Munich; Prestel Verlag, 2002). The Politics of the Artificial: Essays on Design and Design Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). The Idea of Design, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). Co-editor. Discovering Design: Explorations in Design Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995). -

Emotional Techniques Employed and Sources Used by Three Japanese Newspapers to Portray Selected Events Related to World War II Hiroto Fukuda Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-1992 Images of the enemy : emotional techniques employed and sources used by three Japanese newspapers to portray selected events related to World War II Hiroto Fukuda Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Fukuda, Hiroto, "Images of the enemy : emotional techniques employed and sources used by three Japanese newspapers to portray selected events related to World War II" (1992). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 17611. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/17611 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T ? •U Images of the enemy: Emotional techniques employed and sources used by three Japanese newspapers to portray selected events related to World War II by r / 9<± Hiroto Fukuda A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy \ Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1992 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. JAPAN AND THE PACIFIC CONFLICT, 1931-1945 7 III. EMERGENCE OF THE JAPANESE PRESS, 1868-1945 26 IV. PROPAGANDA AND PRESS CONTROLS, 1914-1945 55 War Propaganda of the Allies: U.S. and 61 Great Britain Axis Propaganda: Germany and Japan under 67 Totalitarianism V. -

Graphic Design Studies: What Can It Be? Following in Victor Margolin’S Footsteps for Possible Answers

Design Research Society DRS Digital Library DRS Biennial Conference Series DRS2020 - Synergy Aug 11th, 12:00 AM Graphic design studies: what can it be? Following in Victor Margolin’s footsteps for possible answers Robert George Harland Loughborough University, United Kingdom Follow this and additional works at: https://dl.designresearchsociety.org/drs-conference-papers Citation Harland, R. (2020) Graphic design studies: what can it be? Following in Victor Margolin’s footsteps for possible answers, in Boess, S., Cheung, M. and Cain, R. (eds.), Synergy - DRS International Conference 2020, 11-14 August, Held online. https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2020.372 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at DRS Digital Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in DRS Biennial Conference Series by an authorized administrator of DRS Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLAND Graphic design studies: what can it be? Following in Victor Margolin’s footsteps for possible answers Robert George HARLAND Loughborough University, United Kingdom [email protected] doi: https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2020.372 Abstract: Graphic design studies is proposed as a new way to differentiate practice in graphic design from reflection on that practice. Previous attempts to link design studies and graphic design have fallen short of arguing for graphic design studies, and consequently has not been explicit about how graphic design studies may contribute to better understanding the nature of graphic design practice. This has not been helped by the abstruse nomenclature that confuses graphic design’s relationship to and distinction from other visual practices. -

The Good City: Design for Sustainability

The Good City: Design for Sustainability Conferencia Magistral dictada en el VIII Congreso Internacional de Diseño Forma 2015 La Habana, junio de 2015. Victor Margolin INTRODUCTION In 1972, the Club of Rome published Limits to Growth, a study based on MIT computer models that simulat- Design is undergoing a momentous change. ed the relations between the earth’s resources and Where designers were once known for creating the the human population. As a forecasting tool, Limits visual appearance of products, whether coffee pots to Growth argued that the continued consumption or posters, today they are becoming recognized for of resources at the current rate was unsustainable. their work on the design of services, organizations Its call for new sustainable environmental and social (including government agencies) and even social policies was continued in subsequent studies - the networks. Specializations such as interaction de- World Commission on Environment and Develop- sign, experience design, social design, and design ment’s Our Common Future , a report directed by for sustainability did not exist a few years ago. The Norway’s former Prime Minister, Gro Harlem Brun- older projects of designing artifacts have not dis- tland, and Agenda 21: The Earth Summit Strategy to appeared but the recognition that design can be so Save Our Planet. Both originated within the United much more is growing. Nations system, the latter in conjunction with the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. That conference was fol- Growth involves change and change involves risk. lowed 20 years later by Rio + 20, which produced its To imagine a future that is different from the pres- own set of documents, notably The Future We Want, ent is to risk that the future we seek to bring about that called for change. -

Richard Buchanan, Ph.D

Richard Buchanan, Ph.D. Professor of Design, Management, & Information Systems Department of Design & Innovation Weatherhead School of Management Case Western Reserve University President, International Society of Designers and Managers Co-Editor, Design Issues: A Journal of History, Theory, Criticism Personal Information Department of Design & Innovation Telephone 216-368-0789 (office) Weatherhead School of Management 216-258-4798 (mobile) Peter B. Lewis Building, Room 334 email [email protected] Case Western Reserve University 10900 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, OH 44106 USA 14200 Shaker Blvd. Shaker Heights, OH 44120 USA Education The University of Chicago, Ph.D., 1973 Committee on the Analysis of Ideas & the Study of Methods Field of Study Philosophy, Rhetoric, & the Arts Advisors Richard McKeon (Philosophy & Classics) Wayne C. Booth (English) Dissertation Rhythm and Experience: The Expanding Art of Rhythm in Novel and Film The University of Chicago, A.B., 1968 Committee on the Analysis of Ideas & the Study of Methods Field of Study Philosophy & Rhetoric Advisors Richard McKeon (Philosophy & Classics) Joshua C. Taylor (Art History) Charles W. Wegner (Humanities) Educational Honors Ph.D. Examination with Honors, 1973 Fellowships, 1969-73 Danforth Tutor in the Humanities, 1968-69 Dean’s Lists Scholarships, 1964-68 Current Position Professor of Design, Management, & Information Systems Department of Design & Innovation Weatherhead School of Management Case Western Reserve University 2008-present Co-Editor, Design Issues: A Journal of History, -

Victor Margolin: a Testament

Victor Margolin: A Testament Victor Margolin (1941–2019) was Professor Emeritus of Design History at the University of Illinois, Chicago, a seminal figure in the development of Design History and Design Studies, and a proud collector of corny puns and kitsch objects. Born in Washington DC, Victor enrolled to study English Literature and Film at Columbia University during which time he edited The Columbia Jester, made contributions to MAD magazine, and published two books of puns. Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/desi/article-pdf/36/2/4/1716219/desi_e_00585.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 He graduated from Columbia in 1963 with a Fulbright Fellowship to study at the Institute of Higher Cinema Studies in Paris. On returning to the US Victor eventually settled in Chicago, in 1975. There, after completing a PhD on Russian constructivist designers, his career started to take shape with several publications: American Poster Renaissance: The Great Age of Poster Design 1890–1900 (1975), the edited volume Propaganda: The Art of Persuasion WWII (1976), and The Promise and the Product: 200 years of American Advertising Posters (1979). He then secured a tenured post teaching art and design history at the University of Illinois in 1982, remaining there until his retirement in 2006. Early in his career at the University Victor worked with colleagues to establish the academic journal Design Issues (first published in 1984) becoming its founding editor then remaining a committed member of the editorial board thereafter. From this point on Victor started to edit and co-edit important vol- umes of essays on design titled Design Discourse (1989), The Idea of Design (1995), Discovering Design (1995), and The Designed World: Images, Objects, Environments (2002). -

Visual Art Exhibitions and State Identity in the Late Cold War

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Worlds on View: Visual Art Exhibitions and State Identity in the Late Cold War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, Theory, and Criticism by Nicole Murphy Holland Committee in charge: Professor John C. Welchman, Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Robert Edelman Professor Grant Kester Professor Kuiyi Shen 2010 © Nicole Murphy Holland, 2010 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Nicole Murphy Holland is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved family, Lindsay, Emily, and Peter Holland, whose unswerving support and devotion has made this project possible. iv I didn’t know at the time that John Wayne was an American icon. I thought the painting was just another picture of a cowboy. Vladimir Mironenko, commenting on the painting John Wayne by Annette Lemieux. v Table of Contents Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Dedication ……………………………………………………………………………iv Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………………v Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………… vi Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………… viii Vita…………………………………………………………………………………… x Abstract………………………………………………………………………………xii Introduction……………………………………………………………………………1 Part 1: Theoretical Underpinnings………………………………………… 12 Part 2: Exhibition Functions……………………………………………… 18 Part 3: The Nature of Exhibition Space…………………………………… -

Critical Perspectives and Dialogues About Design and Sustainability

Share this book and dialogues about design sustainability Critical perspectives This is a critical time in design. Concepts and practices of design are changing in response to historical developments in the modes of industrial design production and consumption. Indeed, the imperative of more sustainable development requires profound reconsideration of design today. Theoretical foundations and professional definitions are at stake, with consequences for institutions such as museums and universities as well as for future practitioners. This is ‘critical’ on many levels, from the urgent need to address societal and environmental issues to the reflexivity required to think and do design differently. This book traces the consequences of sustainability for concepts and practices of design. Our basic questions concern whether fundamental concepts that have become institutionalized in design may (or may not) be adequate for addressing contemporary challenges. The book is composed of three main, authored sections, which present different trajectories through a shared inquiry into notions of ‘form’ and ‘critical practice’ in design. In each section, there is a dialogue between text and image–theory and practice, argument and experiment–in which photographic, graphic, facsimile, or other materials act not as illustrations but as arguments in another (designed) form. Each argument interweaves theoretical, historical and practical perspectives that, cumulatively, critique and reconfigure design as we see it. ISBN 978-91-86883-14-0 Critical perspectives and dialogues about design and sustainability Ramia Mazé, Lisa Olausson, Matilda Plöjel, Johan Redström, Christina Zetterlund 7891869 883140 Share this book Critical perspectives and dialogues about design and sustainability Ramia Mazé, Lisa Olausson, Matilda Plöjel, Johan Redström, Christina Zetterlund Axl Books 2013 Acknowledgements This book has been produced under the project Forms of Sustainability, funded by the Swedish Research Council (project number 2008-2257). -

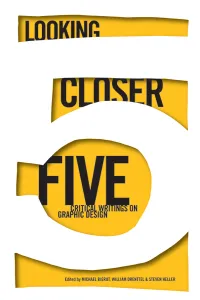

Looking Closer 5

LC5 00.qxd 12/1/06 12:12 PM Page i LOOKING CLOSER 5 edited by: Michael Bierut,William Drenttel, and Steven Heller LC5 00.qxd 4/12/06 10:24 PM Page ii © 2006, Michael Bierut,William Drenttel, and Steven Heller All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. 11 10 09 08 07 54321 Published by Allworth Press An imprint of Allworth Communications, Inc. 10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010 Cover and book design by Pentagram, New York Page composition/typography by Integra Software Services, Pvt., Ltd., Pondicherry, India Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Looking closer. 5, Critical writings on graphic design / [edited by] Steven Heller, Michael Bierut,William Drenttel. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58115-471-9 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 1-581-15471-2 1. Commercial art. 2. Graphic arts. I. Heller, Steven. II. Bierut, Michael. III. Drenttel,William. IV. Title: Critical writings on graphic design. NC997.L6334 2007 741.6—dc22 2006036530 Printed in Canada LC5 00.qxd 12/1/06 12:12 PM Page iii contents FOREWORD—EDITORS / vii INTRODUCTION / ix Steven Heller SECTION I: GRAPHIC DESIGN AS SYSTEM THE GRAND UNIFIED THEORY OF NOTHING: DESIGN, THE CULT OF SCIENCE, AND THE LURE OF BIG IDEAS / 3 Randy Nakamura -

African American Designers in Chicago

Figure 1 Russell Lee, “Candy stand run by Negro. Southside, Chicago, Illinois” (April 1941). Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC- USF34- 038629-D [P&P] LOT 1082. that lynching was a spectacle at home in modern America. Wells designed the pamphlet to shock A THING OF BEAUTY fairgoers’ celebration of progress and move them to action on behalf of African American civil rights. It was an indictment of the racism that festered within the industrial society that had triumphed over Southern slavery. It also reflected Wells’s beliefs that mass-produced print media IS A JOY FOREVER would raise the nation’s consciousness, and that there were entrepreneurs and tradespeople in Chicago to trumpet her political vision.3 A Short History of African American Design in Chicago The publication of The Reason Why illuminates the deep roots of African American design in Chicago. Wells produced and printed the pamphlet with prominent lawyer (and her future husband) Ferdinand L. Barnett, who had been editing the radical Conservator newspaper in The first black designer in Chicago was likely a sign painter—or a milliner, hairdresser, tailor, Chicago since 1878. Born in Nashville in 1859, Barnett was among the first wave of free people barber, printer, typographer or bricklayer.1 When African Americans began to enter the city in of color and freed slaves who settled in Chicago after the Civil War. These early settlers supported significant numbers at the turn of the 20th century, many brought along artistic and practical themselves as merchants and domestic workers who provided services to a mostly white clientele. -

She Ji: the Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation

SHE JI: THE JOURNAL OF DESIGN, ECONOMICS, AND INNOVATION AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 2405-8726 DESCRIPTION . She Ji is a peer-reviewed, trans-disciplinary design journal. We focus on economics and innovation, design process, and design thinking in today's complex socio-technical environment. We are an open access journal with no fees. Our mission is to further design innovation in industry, business, non-profit services, and government through economic and social value creation. Innovation requires integrating ideas, economics, and technology to create new knowledge at the intersection of different fields. She Ji provides a unique forum for this inquiry. Articles in She Ji address the creation, development, distribution, and use of goods and services by societies, organizations, and individuals; the creation and control of socio-technical systems; the strategic and managerial issues these entail; the way that organizations use design; and how design thinking informs wider social, managerial, and intellectual discourses. We also publish articles in research methods and methodology, philosophy, and philosophy of science that support our core journal area. She Ji welcomes articles on a wide range of topics. These include:Design for complex socio-technical systemsScientific, technical, and philosophical problems in fourth-order designDesign driven innovation for social and economic changeDesign practices in management, -

Visualization and Digital Imaging Lab an Interdisciplinary Faculty Research Facility

Visualization and Digital Imaging Lab An Interdisciplinary Faculty Research Facility Report 1999 through Spring 2003 John Goodge (Geology) Antarctic Ice Cave “Pursuing Excellence in Scientific Visualization and Artistic Imaging” MissionStatement The Visualization and Digital Imaging Laboratory was conceived in 1999 through the vision of UMD Chancellor Kathryn Martin as a limited access facility, open to faculty members and their research associates and students whose primary interest is in high-end visualization projects. The laboratory is a collaborative facility of the School of Fine Arts and College of Science and Engineering. It provides a dynamic multi-media environment for design and scientific researchers to conduct original research in the areas of animation, visual imaging, and scientific visualization. The laboratory integrates design research in the areas of computer graphics, two-dimensional imaging, three dimensional imaging, virtual reality applications and sound/image control. Gloria DeFilipps Brush (Art & Design) Untitled Visualization and Digital Imaging Lab • Report 2 Message from the ExecutiveCommittee Since its inception in 1999, the Visualization and Digital Imaging Laboratory has developed into an extremely valuable resource for the faculty at UMD. It has become a place where artists, scientists, educators, and engineers can meet and collaborate, producing multimedia-based output for publication in scientific literature, display at a symposium or museum, or stage performances. Faculty get access to this state-of-the-art facility through application to the lab’s Executive Committee, which is composed of the Dean of the College of Science and Engineering, the Dean of the School of Fine Arts, and the Director of Information Technology Systems and Services.