University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design Research: What Is It? What Is It For?

Design Research: What is it? What is it for? Victor Margolin University of Illinois, Chicago Abstract: The slippage in use between design research as an activity without a precise identity and its characterization of an intellectual field has caused considerable confusion. PhD programs in design are now offered and have become vehicles for producing academic design researchers. This has vastly increased the number of researchers with doctorates but it has not contributed to the coherence of a field and certainly not to the formation of a discipline. As more PhD graduates take up teaching positions, they are under pressure to continue their research and publish it. Without a set of shared questions, they are often left to their own devices to invent a research topic. While the authors adopt what appear to be valid methodologies to guide their investigations, the questions they pose are often narrowly drawn, have no relation to a larger set of issues, and are consequently of little interest or value to other scholars. When it comes to pedagogy, the lack of consensus about what course of studies would constitute a doctorate in design is especially disconcerting. By virtue of not having any consensual curriculum, it is difficult to assess the value of someone’s degree. A big problem in the field is the confusion between an academic degree in design and one in design studies. Instead of perpetuating the term ‘design research,” I suggest adopting the related terms “design’ and ‘design studies” to delineate more precisely the nature of the knowledge or capabilities they signify. Keywords: Design research; Design studies, doctoral design Prelude Since the end of World War II, design has grown in social importance, moving from the styling of products and the production of print material to the design of complex devices, ubiquitous digital media, and even social systems. -

Affluenza - Pages 6/4/05 9:03 AM Page 3

Affluenza - pages 6/4/05 9:03 AM Page 3 Chapter 1 What is affluenza? Af-flu-en-za n. 1. The bloated, sluggish and unfulfilled feeling that results from efforts to keep up with the Joneses. 2. An epidemic of stress, overwork, waste and indebtedness caused by dogged pursuit of the Australian dream. 3. An unsustainable addiction to economic growth.1 Wanting In 2004 the Australian economy grew by over $25 billion, yet the tenor of public debate suggests that the country is in a dire situation. We are repeatedly told of funding shortages for hos- pitals, schools, universities and public transport, and politicians constantly appeal to that icon of Australian spirit, the ‘Aussie battler’. Political rhetoric and social commentary continue to emphasise deprivation—as if we are living in the nineteenth century and the problems facing the country have arisen because we are not rich enough. When the Labor Party lost the federal election in 2004 it declared that, like the conservatives, it must pay more attention to growth and the economy. It would seem that achieving an economic growth rate of 4 per cent is the magic potion to cure all our ills. But how rich do we have to be before we are no longer a nation of battlers? Australia’s GDP has doubled since 1980; at 3 Affluenza - pages 6/4/05 9:03 AM Page 4 AFFLUENZA a growth rate of 3 per cent, it will double again in 23 years and quadruple 23 years after that. Will our problems be solved then? Or will the relentless emphasis on economic growth and higher incomes simply make us feel more dissatisfied? In the private domain, Australia is beset by a constant rumble of complaint—as if we are experiencing hard times. -

Globalization Antenarratives Boje, D

- 17 - Globalization Antenarratives Boje, D. M. 2007. Chapter 17: Globalization Antenarratives. Pp. 505- 549 in Albert Mills, Jeannie C. Helms-Mills & Carolyn Forshaw (Eds). Organizational Behavior in a Global Context. Toronto: Garamond Press (accepted 2005). Globalization antenarratives compete for your attention. Antenarrative is defined as a prestory, an anticipatory bet that the world can be changed in profitable and sometimes progressively humane ways. You are schooled in linear and cyclical Globalization antenarratives, but may not of heard of the rhizome antenarrative. A linear antenarrative tells either a tale of Road to the Top (life just keep getting progressively better) versus a Road to the Bottom (life may be better for the wealthy, but the poor get poorer, & and earth’s resources are being destroyed). Of the two linear narratives, the Business College sells you on the former, the evolution of a succession of Globalizations from imperialisms to empires, where transnational corporations are succeeding nation-states in a world governmentability through the likes of World Trade Organization (WTO), and through contractual trade agreements such as NAFTA. You are exposed to the other linear narrative, Road to Bottom, through TV, watching those protestors outside WTO annual meetings proclaim that transnational corporations are the ruination of living wages, democracy, and Mother Earth. Cyclical Globalization antenarratives pose a different bet, a plot of eternal recurrence (to use Nietzsche’s phrase). Globalization is not a line, not a succession of progressive evolution, where Enlightenment and reason, science and technology, are able to bring about world peace and harmony. Linear Globalization to the cyclical theorists is just illusion, entangled error, not even a persuasive narrative. -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of GENDER, RACE and CLASS Economics 243, Wellesley College, Spring 2018

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF GENDER, RACE AND CLASS Economics 243, Wellesley College, Spring 2018 Professor Julie Matthaei Office Hours: Economics Department Thurs. 5:30-7 pm PNE 423, x2181 & by appointment The Roots of Violence: Wealth without work, Pleasure without conscience, Knowledge without character, Commerce without morality, Science without humanity, Worship without sacrifice, Politics without principles. -- Mahatma Gandhi Objectivity is male subjectivity, made unquestionable. --Adrienne Rich No problem can be solved by the level of consciousness that created it. --Albert Einstein Be the change you want to see in the world. --Mahatma Gandhi Youth should be radical. Youth should demand change in the world. Youth should not accept the old order if the world is to move on. But the old orders should not be moved easily — certainly not at the mere whim or behest of youth. There must be clash and if youth hasn’t enough force or fervor to produce the clash the world grows stale and stagnant and sour in decay. –William Allen White If to change ourselves is to change our worlds, and the relation is reciprocal, then the project of history making is never a distant one but always right here, on the borders of our sensing, thinking, feeling, moving bodies. --J.K. Gibson-Graham Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love. --Martin Luther King Give a man a gun, he can rob a bank. Give a man a bank, and he can rob the world. --Greg Palast Being young and not a REVOLUTIONARY is a contradiction to biology. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

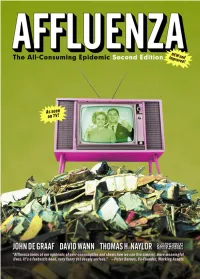

Affluenza: the All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition

An Excerpt From Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition by John de Graaf, David Wann, & Thomas H. Naylor Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers contents Foreword to the First Edition ix part two: causes 125 Foreword to the Second Edition xi 15. Original Sin 127 Preface xv 16. An Ounce of Prevention 133 Acknowledgments xxi 17. The Road Not Taken 139 18. An Emerging Epidemic 146 Introduction 1 19. The Age of Affluenza 153 20. Is There a (Real) Doctor in the House? 160 part one: symptoms 9 1. Shopping Fever 11 part three: treatment 2. A Rash of Bankruptcies 18 171 21. The Road to Recovery 173 3. Swollen Expectations 23 22. Bed Rest 177 4. Chronic Congestion 31 23. Aspirin and Chicken Soup 182 5. The Stress Of Excess 38 24. Fresh Air 188 6. Family Convulsions 47 25. The Right Medicine 197 7. Dilated Pupils 54 26. Back to Work 206 8. Community Chills 63 27. Vaccinations and Vitamins 214 9. An Ache for Meaning 72 28. Political Prescriptions 221 10. Social Scars 81 29. Annual Check-Ups 234 11. Resource Exhaustion 89 30. Healthy Again 242 12. Industrial Diarrhea 100 13. The Addictive Virus 109 Notes 248 14. Dissatisfaction Guaranteed 114 Bibliography and Sources 263 Index 276 About the Contributors 284 About Redefining Progress 286 vii preface As I write these words, a news story sits on my desk. It’s about a Czech supermodel named Petra Nemcova, who once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue. Not long ago, she lived the high life that beauty bought her—jet-setting everywhere, wearing the finest clothes. -

The Privileged Defense: Affluenza's Potential Impact on Counselors In

Article 73 The Privileged Defense: Affluenza’s Potential Impact on Counselors in Court Proceedings Ashley Clark Clark, Ashley, PhD, NCC, DCC, ACS, is a recent graduate from Walden University’s Counselor Education and Supervision program and current program manager for the Rappahannock Rapidan Community Services’ Young Adult Coordinated Care program, an evidence-based early intervention program for adolescents and young adults experiencing the first onset of psychosis. Her research interests include disability issues in counseling and current approaches to multicultural counseling. Abstract Concerns regarding affluenza as an epidemic have been quietly raised in a sociological context and largely ignored in mainstream society for several decades. When the idea of affluenza was raised in the criminal court system by the defense’s evaluating psychologist during a high profile manslaughter case, however, the concerns regarding effects of affluenza rose to the forefront. In fact, the trial of Ethan Couch, product of affluent parents, caused public outcry when an affluenza defense was noted as a potential contributor to a seemingly lenient sentence. This paper provides a brief overview of the history and development of the affluenza concept, evaluates the impact of affluenza through a systemic lens, reviews systemic influences in court rulings, discusses the potential impact of counselors’ roles in the courtroom, and provides a case illustration to demonstrate this potential. Recent court cases involving perceived leniency for Caucasian defendants, which has been attributed to wealth and privilege, have unearthed concerns with the social concept of affluenza. Making headlines in 2013, affluenza was introduced by a court appointed psychologist in the case, State of Texas v. -

Are You Weighed Down by Your Wealth, Troubled by Your Trillions, Guilt-Ridden About Your Golden Lifestyle? You Could Be Suffering from Affluenza

Are you weighed down by your wealth, troubled by your trillions, guilt-ridden about your golden lifestyle? You could be suffering from affluenza. Matthew Lynn seeks help for this crippling condition “Doctor, my brother thinks he’s a chicken.” "They are often in denial. But that doesn't mean the “How long has this been going on?” problems are not there." “Three years. We would have come sooner but we In America, not surprisingly, affluenza is a much needed the eggs.” bigger deal than it has been so far in Europe. Jessie Woody Allen, Annie Hall O'Neill, grand-daughter of a onetime president of General Motors, has set herself up as a leading HERE is no couch in Dr. Ronit Lami's authority on the subject through books such as The office, just computers, files, some Golden Ghetto. "Simply defined," she observes, classy pictures on the walls and a pair "affluenza is a dysfunctional relationship with of comfy armchairs, good for sinking money and wealth or the pursuit of it. Anyone, back into and getting some things off regardless of their net worth, who believes that they your mind. A neatly-dressed, smart, must be rich, that more is always better, is a Toccasionally hesitant woman, Lami is in the process selfcondemned prisoner of the golden ghetto." of setting up Britain's most unusual psychological Even though the economic statistics may now therapy practice. Where other doctors treat make more worrying reading for the wealth neurotics or psychopaths, or the terminally shy or creators, Lami's trade should still be booming. -

THE ISLAMIC GIFT ECONOMY: a BRIEF CONCEPTUAL OUTLINE1 by Adi Setia2

THE ISLAMIC GIFT ECONOMY: A BRIEF CONCEPTUAL OUTLINE1 by Adi Setia2 Introduction The Islamic Gift Economy (IGE) can be envisioned as an integrative economic system based on the operative principles of cooperation (ta‘Āwun), mutual consent (‘an tarĀăin/murĀăĀtin) and partnership (mushĀrakah), and these are in turn founded on the principal ethics of raĄmah (mercy), gratitude (shukr), generosity (karam/iĄsĀn) and moderation (tawĀzun/‘iffah), khilĀfah (trusteeship). IGE’s foundational psycho- cosmological outlook is expressed in the belief that (i) the natural and cultural resources of the world are abundant while (ii) the material needs, wants and desires of human beings are limited and should be limited. The natural and cultural resources of the world seen as blessings and bounties from the Merciful Creator (ni‘am/ĀlĀ’ al-KhĀliq) are abundant and even unlimited in principle because wa in ta‘uddĈ ni‘mataLlĀhi la tuĄsĈhĀ: “if you would count the bounty of AllĀh you cannot exhaust it.”3 Viewed in the light of belief (ąmĀn), these resources are gifts and favours (ĀlĀ’) from the realm of transcendence to which the human ethico- cognitive response is gratitude (shukr) which in turn results in contentment (qanĀ‘ah), hence man will take according to his need but not his greed, for because of abundance there is no anxiety over scarcity that feeds greed (ćamaĂ) and accumulation (takĀthur/jam Ăal-mal wa taĂdąduhu).4 Moreover, shukr itself becomes an existential state of being generative of abundance (ziyĀdah) both material and spiritual, for la’in shakartum 1 This is a revised, extended and fully documented version of the original paper delivered in power point format at three separate waqf workshops in Johannesburg, Durban and Capetown, organized by the National Awqaf Foundation of South Africa (NAFSA) between August 1 to August 8 2009. -

Curing Our Affluenza by NORMAN WIRZBA

Copyright © 2003 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University 89 Curing Our Affluenza BY NORMAN WIRZBA Consumerism has an ambiguous, even destructive, legacy: it has provided status and freedom to some, but has not been successful in treating change and uncer- tainty, inequality and division. As these books discover, our “affluenza”—a feverish obsession to consume mate- rial goods—is not healthy for us or the creation as a whole. Its cure is not a call to dour asceticism, but rather an invitation to receive God’s extravagant grace. early two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville observed in Democracy in America that Americans, though living among the Nhappiest circumstances of any people in the world, are followed by a cloud that habitually hangs over their heads, a cloud that makes them serious, even sad, in the midst of their pleasures. Though they have cause for celebration, they never stop thinking of “the good things they have not got.” Consequently, they pursue prosperity with a “feverish ardor,” tor- mented by the suspicion that they have not chosen the quickest or shortest path to get it. “They clutch everything but hold nothing fast, and so lose grip as they hurry after some new delight.” Were he alive today, de Tocqueville would not need to change his words very much, perhaps adding only that the intensity of our ardor, the scope of our clutching, and the depth of our loss have increased sub- stantially. Having been advised by countless spiritual guides that money and the pursuit of material comfort will not bring us happiness, why do we still maintain this ambition as a personal, even national, quest? What is becom- 90 Consumerism ing clear to many in our society is that consumerism is not healthy for us or for the creation as a whole, and that it leads to anxiety, stress, boredom, and indigestion, all maladies with tremendous personal and social costs. -

Victor Margolin

VICTOR MARGOLIN 1307 S. Wabash #702 Dept. of Art History Chicago, IL 60605 University of Illinois 935 W. Harrison St Chicago, IL. 60607-7039 tel./312-413-2463 fax/312-413-2460 Education 1979–1981 Union Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio. Ph.D. in Design History. Dissertation: "The Transformation of Vision: Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, and László Moholy-Nagy as Graphic Designers, 1917-1933." 1963–1964 Fulbright Scholar, Institute of Higher Cinema Studies, Paris, France 1959–1963 Columbia University, New York. Bachelor of Arts. Majored in English. Film history and production courses at the Center for Mass Communication Current Position 1982–present University of Illinois at Chicago, History of Architecture and Art Department. Professor of Art and Design History (Department Chair, 1990-1993); Director of Graduate Studies, 2000- 2001 University Honors Fellow of the Institute for the Humanities, 1985 - 1986 Fellow of the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy, 1998--2000 UIC Teaching Recognition Program Award, 1997 Silver Circle Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1991, 1997; nominated three additional times for the award UIC Excellence in Teaching Award, 2000 Featured as Outstanding Teacher in the UIC Annual Report, 2001 University Scholar, 2000-2001 Publications Books Culture is Everywhere: Selections from the Museum of Corntemporary Art (Munich; Prestel Verlag, 2002). The Politics of the Artificial: Essays on Design and Design Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917-1946 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). The Idea of Design, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). Co-editor. Discovering Design: Explorations in Design Studies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995). -

Emotional Techniques Employed and Sources Used by Three Japanese Newspapers to Portray Selected Events Related to World War II Hiroto Fukuda Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-1992 Images of the enemy : emotional techniques employed and sources used by three Japanese newspapers to portray selected events related to World War II Hiroto Fukuda Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Fukuda, Hiroto, "Images of the enemy : emotional techniques employed and sources used by three Japanese newspapers to portray selected events related to World War II" (1992). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 17611. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/17611 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T ? •U Images of the enemy: Emotional techniques employed and sources used by three Japanese newspapers to portray selected events related to World War II by r / 9<± Hiroto Fukuda A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Signatures have been redacted for privacy \ Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1992 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. JAPAN AND THE PACIFIC CONFLICT, 1931-1945 7 III. EMERGENCE OF THE JAPANESE PRESS, 1868-1945 26 IV. PROPAGANDA AND PRESS CONTROLS, 1914-1945 55 War Propaganda of the Allies: U.S. and 61 Great Britain Axis Propaganda: Germany and Japan under 67 Totalitarianism V.