Project Activities -DVV July 2018 (To Upload)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Value of Ecosystem Services Obtained from the Protected Forest of Cambodia: the Case of Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park ⇑ Abu S.M.G

Ecosystem Services 26 (2017) 27–36 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecosystem Services journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecoser The value of ecosystem services obtained from the protected forest of Cambodia: The case of Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park ⇑ Abu S.M.G. Kibria a, , Alison Behie a, Robert Costanza b, Colin Groves a, Tracy Farrell c a College of Arts & Social Science, The Australian National University, ACT 2601, Australia b College of Asia Pacific, The Australian National University, ACT 2601, Australia c Conservation International, Greater Mekong Region, Phnom Penh Center, Sothearos Corner Sihanouk Blvd, Phnom Penh, Cambodia article info abstract Article history: This research provides for the first time a valuation of Veun Sai-Siem Pang National Park (VSSPNP) in Received 16 June 2016 Cambodia, which is a forest largely unfamiliar to the international community yet extremely significant Received in revised form 10 May 2017 in terms of biodiversity value. This study aimed to measure the monetary and non-monetary values of Accepted 22 May 2017 ecosystem services (ESS) of the forest. We estimated the total annual contribution of VSSPNP was US $129.84 million. Its primary contribution was air purification (US$56.21 million yrÀ1) followed by water storage (US$32.31 million yrÀ1), soil-erosion reduction (US$22.21 million yrÀ1), soil-fertility improve- Keywords: À À ment (US$9.47million yr 1), carbon sequestration (US$7.87 million yr 1), provisioning services (US Ecosystem services $1.76 million yrÀ1) and recreation (US$0.02 million yrÀ1). Traditionally the forest is used for timber and Monetary values Non-monetary values non-timber forest products, which in fact, composed only 1.36% of the total benefits. -

Final Report on Survey Of

FINAL REPORT ON SURVEY OF March 2013 Supported by Committee For Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL) #138, Str 122 Teuk Laak 1, Toulkork, Phnom Penh xumE®hVl Box: 1145 COMFREL Tel: 023 884 150 Fax:023 885 745 Email³ [email protected], [email protected] Website³ www.comfrel.org Contents FORWARD ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 VOTER LIST, VOTER REGISTRATION AND AUDIT OF THE VOTER LIST (SVRA PLUS) FOR THE 2013 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ELECTION ..................................................................................................................................... 7 1. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 7 2. PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. 12 3. PROJECT OUTPUTS ................................................................................................................................... 14 4. SURVEY LIMITATIONS AND LESSON LEARNED ........................................................................................... 15 5. SUMMARY AND PRINCIPLE FINDINGS ....................................................................................................... 15 6. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................................... -

Annual Narrative Report 2012

GgÁkarGnupléRBeQI Non-Timber Forest Products __________________________________________________ Annual Narrative Report for 2012 to ICCO & Kerk in Actie from NTFP Non-Timber Forest Products Organization Ban Lung, Ratanakiri Province, CAMBODIA Feb 28 2012 1 Contact addresses: Non-Timber Forest Products Organization (NTFP) Mr. Long Serey, Executive Director Email: [email protected] NTFP Main Office (Ratanakiri) NTFP Sub-office (Phnom Penh) Village 4, Sangkat Labanseak #16 Street 496 [Intersects St. 430] Banlung, Ratanakiri Province Sangkat Phsar Deom Skov CAMBODIA Khan Chamkarmorn Tel: (855) 75 974 039 Phnom Penh, CAMBODIA P.O. Box 89009 Tel: (855) 023 309 009 Web: www.ntfp-cambodia.org 2 Table of Contents Acronyms Executive summary 1. Overview of changes and challenges in the project/program context 1.1 Implications for implementation 2. Progress of the project (summary) ʹǤͳ ǯrograms and projects during 2012 2.2 Contextualized indicators and milestones 2.3 Other issues 2.4 Monitoring of progress by outputs and outcomes 3. Reflective analysis of implementation issues 3.1 Successful issue - personal and community perspectives on significant change 3.1.1 Account of Mr Bun Linn, a Kroeung ethnic 3.1.2 Account of Mr Dei Pheul, a Kawet ethnic 3.1.3 Account of Ms Seung Suth, a Tampuan ethnic 3.1.4 Account of Ms Thav Sin, a Tampuan ethnic 3.2 Unsuccessful issue (implementation partially done) 4. Lessons learned to date, challenges and solutions 4.1 Reference to KCB 4.2 Reference to youth (IYDP) 4.3 Reference to IPWP 4.4 Reference to CC 4.5 Reference to CF 4.6 Reference to CMLN 5. -

Cambodian Journal of Natural History

Cambodian Journal of Natural History Rediscovery of the Bokor horned frog Four more Cambodian bats How to monitor a marine reserve The need for community conservation areas Eleven new Masters of Science December 2013 Vol 2013 No. 2 Cambodian Journal of Natural History ISSN 2226–969X Editors Email: [email protected] • Dr Jenny C. Daltry, Senior Conservation Biologist, Fauna & Flora International. • Dr Neil M. Furey, Research Associate, Fauna & Flora International: Cambodia Programme. • Hang Chanthon, Former Vice-Rector, Royal University of Phnom Penh. • Dr Nicholas J. Souter, Project Manager, University Capacity Building Project, Fauna & Flora International: Cambodia Programme. International Editorial Board • Dr Stephen J. Browne, Fauna & Flora International, • Dr Sovanmoly Hul, Muséum National d’Histoire Singapore. Naturelle, Paris, France. • Dr Martin Fisher, Editor of Oryx—The International • Dr Andy L. Maxwell, World Wide Fund for Nature, Journal of Conservation, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Cambodia. • Dr L. Lee Grismer, La Sierra University, California, • Dr Jörg Menzel, University of Bonn, Germany. USA. • Dr Brad Pett itt , Murdoch University, Australia. • Dr Knud E. Heller, Nykøbing Falster Zoo, Denmark. • Dr Campbell O. Webb, Harvard University Herbaria, USA. Other peer reviewers for this volume • Dr Judith Eger, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, • Berry Mulligan, Fauna & Flora International, Phnom Canada. Penh, Cambodia. • Pisuth Ek-Amnuay, Siam Insect Zoo & Museum, • Prof. Dr. Annemarie Ohler, Muséum national Chiang Mai, Thailand. d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France. • Dr James Guest, University of New South Wales, • Dr Jodi Rowley, Australian Museum, Sydney, Sydney, Australia. Australia. • Dr Kristofer M. Helgen, Smithsonian Institute, • Dr Manuel Ruedi, Natural History Museum of Washington DC, USA. Geneva, Geneva, Switz erland. -

Upper Secondary Education Sector Development Program: Construction of 73 Subprojects Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Project Number: 47136-003 Loan 3427-CAM (COL) July 2019 Kingdom of Cambodia: Upper Secondary Education Sector Development Program (Construction of 73 sub-projects: 14 new Secondary Resource Centers (SRCs) in 14 provinces, 5 Lower Secondary School (LSSs) upgrading to Upper Secondary School (USSs) in four provinces and 10 overcrowded USSs in six provinces) and 44 Teacher Housing Units or Teacher Quarters (TQs) in 21 provinces) This initial environmental assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP -- Affected people CCCA -- Cambodia Climate Change Alliance CMAC -- Cambodian Mine Action Centre CMDG -- Cambodia Millennuum Development Goals CLO – Community Liaison Officer EA – Executing Agency EARF -- Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EHS -- Environmental and Health and Safety EHSO – Environmental and Health and Safety Officer EIA -- Environmental Impact Assessment EMIS – Education Management Information System EMP – Environmental Management Plan EO – Environment and Social Safeguard Officer ERC – Education Research -

Carbon Storage and REDD+ in Virachey National Park Chou Phanith and Fujikawa Kiyoshi ASSIA Working Paper Series 21-03 August, 20

Carbon Storage and REDD+ in Virachey National Park Chou Phanith and Fujikawa Kiyoshi ASSIA Working Paper Series 2 1 - 0 3 August, 2021 Applied Social System Institute of Asia (ASSIA) Nagoya University 名古屋大学 アジア共創教育研究機構 The views expressed in “ ASSIA Working Papers” are those of the authors and not those of Applied Social System Institute of Asia or Nagoya University. (Contact us: https://www.assia.nagoya- u.ac.jp/index.html) ASSIA Working Paper Series 21-03 Carbon Storage and REDD+ in Virachey National Park: Possibility of Collaboration with Japan Chou Phanith * and Fujikawa Kiyoshi† Table of contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 1 Keywords ................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 2. The Current Status of REDD+ in Cambodia ......................................................... 3 3. Methods ............................................................................................................... 6 4. Results ................................................................................................................. 9 5. Conclusion ......................................................................................................... 19 Acknowledgment ................................................................................................... -

Safeguard Policies on Indigenous Peoples and Involuntary Resettlement

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund Social Assessment, Including Indigenous Peoples’ Plan Community Forestry & Community Patrols for Gibbons protection at the Veun Sai Siem Pang Conservation Area - Cambodia. Above: Nomascus annamensis at VVSPCA© Poh Kao Right: Community Forestry demarcation team (Forestry Administration officer and villagers representatives April 2014 Backae village, Siempang District © Poh Kao Empowering local communities to engage in conservation and management of priority Key Biodiversity Areas and threatened primate in the Veun Sai Siem Pang Conservation Area - Cambodia. Organization: Non Timber Forest Products Ngo Cambodia Application Code: 65944 Date: March 2016 1 Statement of Need In line with CEPF requirements, we confirm that the proposed project does work in areas where indigenous peoples live and the proposed activities might change their behaviors in relation to natural resources management and utilization. Together with local partners and stakeholders, NTFP’s Programme has prepared this document to demonstrate how the project will comply with CEPF’s Safeguard Policies on Indigenous Peoples and Involuntary Resettlement. Project Background The project goal is to obtain official status of protection for Veun Sai Siem Pang Conservation Area (VSSPCA) through Community Forestry creation and/or ICCA; and collaboration between local communities, contributing to reduce illegal forestry and maintain gibbon population in Veun Sai Siem Pang Forest over a two year period. The overall objective is the support to Veun Sai Siem Pang CA protection through community rights, to create Community Forestry and/or ICCA and to patrol the forest to mitigate biodiversity loss with a special focus on gibbon protection. Objectives include 1) Registration of Community Forestry recognized by FA 2) creation of Community patrols and CBO ; 3) Monitoring of forest crimes and data base with quality information are created ; 4) Creation of the Veun Sai Siem Pang Network; and 5) linking VSSPCA network with existing national network. -

Phnom Penh O Mes

103° 105° 107° :)eµ :)m’Ùy SAKOU Samoth 14° Géographie 13° du Cambodge NaÙtNkø;&=)n 11° 11° 6 NaÙt:I"t§:p 103° 105° 107° 5 105° 7 j ?Ó;§< a 7 Preah Vihear Banlung St.Trèng Sisophon Angkor 4NaÙtqH)nmp Battambang 3 1 13° Mon 13° Krati <µp§a; Mékong é Pursa Stung Sèn ts t 2 Card Kg.Cham am Phnom Penh o mes Sihanoukville KepDaunKeo Golfe de Mer SAKOU SAMOTH Thaïlande de Chine Magazine Angkor Vat . Paris - Décembre 2013 105° ISBN 2-9524557-5-9 . Dépôt légal : Bibliothèque nationale de France . Décembre 2013 . ISSN: 1162-1680 Utilisation du sol dans les années 1970 et cours d’eau THAILANDE Samrong Banlung Poïpet Sisophon Krong Preah Vihear Païlin Pursat Krong Stung Sèn Senmonorom Kg.Chhnang Agriculture diffuse Forêt tropicale dense Kg.Cham Forêt sèche et savane Phnom Penh Marécages Khémarak VIETNAM Phouminville Châr Môn Prey Vèng sens du courant de juin à octobre Mangroves Takhmau sens du courant de novembre à mai Grande pêche en eau douce N GOLFE DE Svay Rieng THAILANDE Daun Keo Les cultures principales (riz, caoutchouc) restent toujours les mêmes Bokor Sihanoukville Kampot Kep Koh Trâl Preah Vihear Samrong Réseau routier : Distances de Phnom Penh à la ville de : Phnom Kulean Siem Pang Borkeo Battambang : 291 km Prey Vèng : 91 km Angkor Stung Trèng Siem Reap : 314 km Svay Rieng : 124 km Tonl Phnom Dèk Samrong : 440 km g Krong Chbar Môn : 48 km Battambang Pich Rada Païlin Krong Stung Sèn : 169 km Krong Daun Keo : 78 km kon Sap Kg.Thom M Krong Preah Vihear: 292 km Kampot : 148 km Bou Sra des cardam Kratié Pursat : 186 km Kh.Phouminville -

Pdf IWGIA Book Land Alienation 2006 EN

Land Alienation in Indigenous Minority Communities - Ratanakiri Province, Cambodia Readers of this report are also directed toward the enclosed video documentary made on this topic in October 2005: “CRISIS – Indigenous Land Crisis in Ratanakiri”. Also relevant is the Report “Workshop to Seek Strategies to Prevent Indigenous Land Alienation” published by NGO Forum in collaboration with CARE Cambodia, 28-20 March 2005. - Final Draft- August 2006 Land Alienation in Indigenous Minority Communities - Ratanakiri Province, Cambodia Table of Contents Contents............................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 4 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 5 Executive Summary – November 2004................................................................................. 6 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology...................................................................................................................... 10 The Legal Situation.............................................................................................................. 11 The Situation in January 2006 ............................................................................................ -

Mapping Communities: Ethics, Values, Practice

MAPPINGCOMMUNITIES ETHICS, VALUES, PRACTICE Edited by Jefferson Fox, Krisnawati Suryanata, and Peter Hershock ISBN # 0-86638-201-1 Published by the East-West Center Honolulu, Hawaii © East-West Center, 2005 The East-West Center is an education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen relations and understanding among the nations of Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center promotes the development of a stable, prosperous, and peaceful Asia Pacific community through cooperative study, training, dialogue, and research. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, with additional support provided by private agencies, individuals, foundations, corporations, and Asia Pacific governments. A PDF file and information about this publication can be found on the East-West Center website at www.EastWestCenter.org. For more information, please contact: Publication Sales Office East-West Center 1601 East-West Road Honolulu, HI 96848-1601 USA Telephone: (808) 944-7145 Facsimile: (808) 944-7376 Email: [email protected] Website: www.EastWestCenter.org iv TABLE OF CONTENTS vi Contributors vii Acronyms viii Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION Jefferson Fox, Krisnawati Suryanata, Peter Hershock, and Albertus Hadi Pramono 11 COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PARTICIPATORY MAPPING PROCESSES IN NORTHERN THAILAND Pornwilai Saipothong, Wutikorn Kojornrungrot, and David Thomas 29 EFFECTIVE MAPS FOR PLANNING SUSTAINABLE LAND USE AND LIVELIHOODS Prom Meta and Jeremy Ironside 43 UNDERSTANDING AND USING COMMUNITY MAPS AMONG INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES IN RATANAKIRI PROVINCE, CAMBODIA Klot Sarem, Jeremy Ironside, and Georgia Van Rooijen 57 EMPOWERING COMMUNITIES THROUGH MAPPING Zheng Baohua 73 DEVELOPMENT OF RURAL COMMUNITY CAPACITY THROUGH SPATIAL INFORMATION TECHNOLGY Yvonne Everett and Phil Towle 87 COMMUNITY-BASED MAPPING Mark Bujang 97 INSTITUTIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF COUNTER-MAPPING TO INDONESIAN NGO’s Albertus Hadi Pramono 107 BUILDING LOCAL CAPACITY IN USING SIT FOR NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN EAST SUMBA, INDONESIA Martin Hardiono, H. -

11925773 07.Pdf

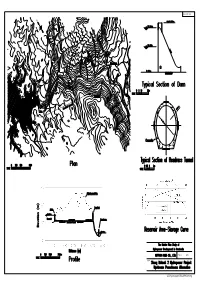

Final Report Appendix-B Results of Natural Environment Survey by Subcontractor APPENDIX-B RESULTS OF NATUAL ENVIRONMENT SURVEY BY SUBCONTRACTOR NATURAL ENVIRONMENT The rapid economic growth of Cambodia in recent years drives a huge demand for electricity. A power sector strategy 1999–2016 was formulated by the government in order to promote the development of renewable resources and reduce the dependency on imported fossil fuel. The government requested technical assistance from Japan to formulate a Master Plan Study of Hydropower Development in Cambodia. The objective of this paper is to survey the natural and social environment of 10 potential hydropower projects in Cambodia that can be grouped into six sites as listed below. This survey constitutes part of the Master Plan Study of Hydropower Development in Cambodia. The objective of the survey is to gather baseline information on the current conditions of the sites, which will be used as input for a review and prioritisation of the selected project sites. This report indicate the natural environment of the following projects on 6 basins. Original Site No. Name of Project Provice Protected Area (Abbreviation) 1 No. 12, 13 & 14 Prek Liang I, IA, II Ratanak Kiri Virachey National Park (VNP) 2 No. 7 & 8 Lower Se San II & Lower Stung Treng - Sre PokII 3 No. 29 Bokor Plateau Kampot Bokor National Park (BNP) 4 No. 22 Stung Kep II Koh Kong Southern Cardamom Protected Forest (SCPF) 5 No. 16 & 23 Middle and Upper Stung Koh Kong Central Cardamom Protected Forest Russey Chrum (CCPF) 6 No. 20 & 21 Stung Metoek II, III Pursat & Koh Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary Kong (PSWS) No. -

LOGS and PATRONAGE: SYSTEMATIC ILLEGAL LOGGING and the DESTRUCTION of STATE FORESTS and PROTECTED AREAS in Rattanakiri and Stung Treng Provinces, Cambodia

evTikaénGgÁkarminEmnrdæaPi)al sþIBIkm<úCa The NGO Forum on Cambodia eFIVkarrYmKñaedIm,IPaBRbesIreLIg Working Together for Positive Change LOGS AND PATRONAGE: SYSTEMATIC ILLEGAL LOGGING AND THE DESTRUCTION OF STATE FORESTS AND PROTECTED AREAS in Rattanakiri and Stung Treng Provinces, Cambodia June 2015 Logs and Patronage: Systematic illegal logging and the destruction of state forests and protected areas in Rattanakiri and Stung Treng Provinces, Cambodia Printed Date: June 2015 Published by: The NGO Forum on Cambodia Land and Livelihoods Program Forestry Rights Project All photographs in this report are provided by Investigation Team DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this report are those solely of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of The NGO Forum on Cambodia. While the content of this report may be quoted and reproduced, acknowledgement and authorization of the report’s authors and publisher would be appreciated. © The NGO Forum on Cambodia, June 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We, a union of NGOs, would like to express our sincere thanks to the individuals from various communities and organizations for their support and assistance. Special thanks must be given to Mr. Thomas Blissendem from the Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia for providing the legal analysis of the Try Pheap Group’s luxury timber business. This research is intended to give new vigour to a forestry reform in Cambodia. This report is dedicated to the late Chutt Wutty and all forest defenders in Cambodia. CONTENTSCONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................i