Housing and the Urban Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics Lecture 5: Cities in Developing Countries J. Vernon Henderson (LSE) 9 July 2020 Outline of talk • Urbanization: Moving to cities • Where are the frontiers of urbanization • Does the classic framework apply? • “Spatial equilibrium” in developing countries • Issues and patterns • Structural modelling • Data needed • Relevant questions and revisions to baseline models • Within cities • Building the city: investment in durable capital • Role of slums • Land and housing market issues Frontiers of urbanization • Not Latin America and not much of East and West Asia • (Almost) fully urbanized (60-80%) with annual rate of growth in urban share growth typically about 0.25% • Focus is on clean-up of past problems or on distortions in markets • Sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-East Asia • Urban share 35-50% and annual growth rate in that share of 1.2- 1.4% • Africa urbanizing at comparatively low-income levels compared to other regions today or in the past (Bryan at al, 2019) • Lack of institutions and lack of money for infrastructure “needs” Urbanizing while poor Lagos slums, today Sewers 1% coverage London slums, 120 years ago Sewer system: 1865 Models of urbanization • Classic dual sector • Urban = manufacturing; rural = agriculture • Structural transformation • Closed economy: • Productivity in agriculture up, relative to limited demand for food. • Urban sector with productivity growth in manufacturing draws in people • Open economy. • “Asian tigers”. External demand for manufacturing (can import food in theory) • FDI and productivity growth/transfer Moving to cities: bright lights or productivity? Lack of structural transformation • Most of Africa never really has had more than local non-traded manufactures. -

544 Urban Growth

544 urban growth changes in spatially delineated public goods. the physical structure of cities and how it may change as International Economic Review 45, 1047-77. cities grow. It also focuses on how changes in commuting Tolley, G. 1974. The welfare economics of city bigness. costs, as well as the industrial composition of national Journal of Urban Economics 1, 324-45. output and other technological changes, have affected the United Nations Population Division. 2004. World Population growth of cities. Another direction has focused on Prospects: The 2004 Revision Population Database. Online. understanding the evolution of systems of cities - that Available at http://esa.un.orglunpp, accessed 28 June is, how cities of different sizes interact, accommodate and 2005. share different functions as the economy develops and what the properties of the size distribution of urban areas are for economies at different stages of development. Do the properties of the system of cities and of city size urban growth distribution persist while national population is growing? Urban growth - the growth and decline of urban Finally, there is a literature that studies the link between areas - as an economic phenomenon is inextricably urban growth and economic growth. What restrictions linked with the process of urbanization. Urbanization does urban growth impose on economic growth? What itself has punctuated economic development. The spatial economic functions are allocated to cities of different distribution of economic activity, measured in terms of sizes in a growing economy? Of course, all of these lines population, output and income, is concentrated. The of inquiry are closely related and none of them may be patterns of such concentrations and their relationship fully understood, theoretically and empirically, on its to measured economic and demographic variables con own. -

State Failure in Developing Countries and Strategies of Institutional Reform

State Failure in Developing Countries and Strategies of Institutional Reform Mushtaq H. Khan Department of Economics, SOAS, University of London. Abstract: The analysis of state failure and the policy debate have been driven by two very different underlying views of what the state does. The first, which we call the “service- delivery” view says the role of the state is to provide law and order, stable property rights, key public goods and welfarist redistributions. In failing to provide these, state failure contributes to economic under-performance and poverty. State failure of this type is in turn related to an inter-dependent constellation of governance failures including corruption and rent-seeking, distortions in markets and the absence of democracy. All of these need to be addressed to focus the state on its core service-delivery tasks. The second locates the developing country state in the context of “social transformation”: the dramatic transition these countries are going through as traditional production systems collapse and a capitalist economy begins to emerge. Dynamic transformation states have heavily intervened in property rights and devised rent-management systems to accelerate the capitalist transition and the acquisition of new technologies. State failure according to this view has been driven by the lack of institutional capacities in these respects, and more importantly, the incompatibility of institutional capacities with pre-existing distributions of power. An examination of the econometric data and historical evidence raises serious doubts as to whether the governance reforms suggested by the first view can improve growth, while the need for reforms identified by the second view are much better supported. -

Well Isnjt That Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Well Isn’tThat Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics: A View From Economic Theory Marcus Berlianty February 2005 I thank Gilles Duranton, Sukkoo Kim, Fan-chin Kung and Ping Wang for comments, implicating them only for baiting me. yDepartment of Economics, Washington University, Campus Box 1208, 1 Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 USA. Phone: (314) 935-8486, Fax: (314) 935-4156, e-mail: [email protected] 1 As a younger and more naïve reviewer of the …rst volume of the Handbook (along with Thijs ten Raa, 1994) more than a decade ago, it is natural to begin with a comparison for the purpose of evaluating the progress or lack thereof in the discipline.1 Then I will discuss some drawbacks of the New Economic Geography, and …nally explain where I think we should be heading. It is my intent here to be provocative2, rather than to review speci…c chapters of the Handbook. First, volume 4 cites Masahisa Fujita more than the one time he was cited in volume 1. Volume 4 cites Ed Glaeser more than the 4 times he was cited in volume 3. This is clear progress. Second, since the …rst volume, much attention has been paid by economists to the simple question: “Why are there cities?” The invention of the New Economic Geography represents an important and creative attempt to answer this question, though it is not the unique set of models capable of addressing it. -

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 [email protected]

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 813.289.88L.L, [email protected] - RBANECONOMICS.COM ECONOMICS INC. MICHAEL A. MCELVEEN, MAI, CCIM, CRE President Urban Economics, Inc. 810 South Sterling Avenue Tampa, FL 33609-4516 Urban Economics, Inc. - Tampa, Florida - Michael A. McElveen is president of Urban Economics, Incorporat ed, a real estate consultancy providing econometrics, valuation, spat ia l analytics, economic impact and st igma effect advice and opinions for 31 years. The focus of Michael A. McElveen has been expert witness t estimony, having testified numerous times at either a jury trial , hearing or by deposition. Mr. McElveen has been accepted by the Ninth Jud icial Circuit Court of Florida an d the Thirteenth Judicial Circuit Court as an expert in the use of econometrics in real estate. Mr. McElveen has performed the following econometric studies: • Econometric study of the marginal impact of an additional 18-hole golf course and equestrian facility o n the value of residential lots, Lake County, FL; • Sales price index trend of fractured condominium sales in O sceola County; • Econometric study of the rent effect of deficient parking at neighborhood retail centers, Charlotte County, FL; • Economet ric study of the sales price effect of location and community w aterfront in Martin County, FL; and • Hedonic regression model analysis of the sales price effect vehicul ar traffic volume and roadway elevation on nearby ho mes in Duval County, Florida. Ed uca ti o n Bachelo r of Arts Finance, University of South Bachelor of Science, Florida State University Florida Professional Associations Appraisal Institute (MAI), Certificate No. -

Mumbai Law and Economics of Institutions

Instructor: Jayati Sarkar email: [email protected] skype id: jayati.sarkar13 LAW AND ECONOMICS OF INSTITUTIONS EMLE Third Term: April – June 2020 Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, INDIA Course Description This course is designed to expose the student to fundamental theoretical perspectives and empirical research that have developed over the years to study the emergence and functions of institutions, with special emphasis placed on law as an institution. Insights gained in the course will be helpful in understanding the role of institutions in development, and in analysing the process of economic change. The course is divided into three main sections, namely (i) why study institutions matter (ii) theoretical perspectives in institutional economics, and (iii) how institutions matter. Topics covered under these sections include how social, political and legal institutions impact economic development, bounded rationality and institutions, the function of institutions in mitigating collective action problems, rent seeking, interest groups and policy formulation, role of institutions in reduction of transaction costs and the role of rules and norms in coordinating and protecting institutions. Course Requirement In view of the Covid 19 pandemic, the course this year will be in the form of self study with directed readings as specified in this reading list. Soft copies of all readings in this list will be provided to you.. Power point presentations of lectures that go with the readings will also be sent to you on pre-specified dates. There will be 12 such power points presentations to be covered over a span of four weeks. In these four weeks, we will meet online via Skype every Tuesday at a mutually convenient time to discuss any questions that you may have on the lecture notes and readings. -

Are We There Yet? IZA DP No

IZA DP No. 6934 Are We There Yet? Time for Checks and Balances on New Institutionalism Murat Iyigun October 2012 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Are We There Yet? Time for Checks and Balances on New Institutionalism Murat Iyigun University of Colorado and IZA Discussion Paper No. 6934 October 2012 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

Theory of International Politics

Theory of International Politics KENNETH N. WALTZ University of Califo rnia, Berkeley .A yy Addison-Wesley Publishing Company Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California London • Amsterdam Don Mills, Ontario • Sydney Preface This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Political Science Theory is fundamental to science, and theories are rooted in ideas. The National Science Foundation was willing to bet on an idea before it could be well explained. The following pages, I hope, justify the Foundation's judgment. Other institu tions helped me along the endless road to theory. In recent years the Institute of International Studies and the Committee on Research at the University of Califor nia, Berkeley, helped finance my work, as the Center for International Affairs at Harvard did earlier. Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and from the Institute for the Study of World Politics enabled me to complete a draft of the manuscript and also to relate problems of international-political theory to wider issues in the philosophy of science. For the latter purpose, the philosophy depart ment of the London School of Economics provided an exciting and friendly envi ronment. Robert Jervis and John Ruggie read my next-to-last draft with care and in sight that would amaze anyone unacquainted with their critical talents. Robert Art and Glenn Snyder also made telling comments. John Cavanagh collected quantities of preliminary data; Stephen Peterson constructed the TabJes found in the Appendix; Harry Hanson compiled the bibliography, and Nacline Zelinski expertly coped with an unrelenting flow of tapes. Through many discussions, mainly with my wife and with graduate students at Brandeis and Berkeley, a number of the points I make were developed. -

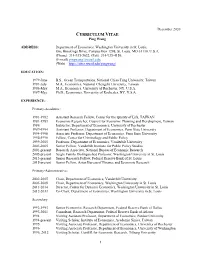

CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang

December 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang ADDRESS: Department of Economics, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1208, St. Louis, MO 63130, U.S.A. (Phone) 314-935-5632; (Fax) 314-935-4156; (E-mail) [email protected]; (Web) https://sites.wustl.edu/pingwang/ EDUCATION: 1979-June B.S., Ocean Transportation, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan 1981-July M.A., Economics, National Chengchi University, Taiwan 1986-May M.A., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. 1987-May Ph.D., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. EXPERIENCE: Primary-Academic: 1981-1982 Assistant Research Fellow, Center for the Quality of Life, TAIWAN 1981-1983 Economic Researcher, Council for Economic Planning and Development, Taiwan 1986 Instructor, Department of Economics, University of Rochester 1987-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Fellow, Center for Criminology and Public Policy 1999-2005 Professor, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University 2001-2005 Senior Fellow, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies 2001-present Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research 2005-present Seigle Family Distinguished Professor, Washington University in St. Louis 2013-present Senior Research Fellow, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2015-present Senior Fellow, Asian Bureau of Finance and Economic Research Primary-Administrative: 2002-2005 Chair, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University -

Place-Based Policies

CHAPTER 18 Place-Based Policies David Neumark*, Helen Simpson† *UCI, NBER, and IZA, Irvine, CA, USA †University of Bristol, CMPO, OUCBT and CEPR, Bristol, UK Contents 18.1. Introduction 1198 18.2. Theoretical Basis for Place-Based Policies 1206 18.2.1 Agglomeration economies 1206 18.2.2 Knowledge spillovers and the knowledge economy 1208 18.2.3 Industry localization 1209 18.2.4 Spatial mismatch 1210 18.2.5 Network effects 1211 18.2.6 Equity motivations for place-based policies 1212 18.2.7 Summary and implications for empirical analysis 1213 18.3. Evidence on Theoretical Motivations and Behavioral Hypotheses Underlying Place-Based Policies 1215 18.3.1 Evidence on agglomeration economies 1215 18.3.2 Is there spatial mismatch? 1217 18.3.3 Are there important network effects in urban labor markets? 1219 18.4. Identifying the Effects of Place-Based Policies 1221 18.4.1 Measuring local areas where policies are implemented and economic outcomes in those areas 1222 18.4.2 Accounting for selective geographic targeting of policies 1222 18.4.3 Identifying the effects of specific policies when areas are subject to multiple interventions 1225 18.4.4 Accounting for displacement effects 1225 18.4.5 Studying the effects of discretionary policies targeting specific firms 1226 18.4.6 Relative versus absolute effects 1229 18.5. Evidence on Impacts of Policy Interventions 1230 18.5.1 Enterprise zones 1230 18.5.1.1 The California enterprise zone program 1230 18.5.1.2 Other recent evidence for US state-level and federal programs 1237 18.5.1.3 Evidence from other countries 1246 18.5.1.4 Summary of evidence on enterprise zones 1249 18.5.2 Place-based policies that account for network effects 1250 18.5.3 Discretionary grant-based policies 1252 18.5.3.1 Summary of evidence on discretionary grants 1259 18.5.4 Clusters and universities 1261 18.5.4.1 Clusters policies 1261 18.5.4.2 Universities 1264 18.5.4.3 Summary of evidence on clusters and universities 1267 Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics,Volume5B © 2015 Elsevier B.V. -

Law and Economics: Its Glorious Past and Cloudy Future Richarda

Law and Economics: Its Glorious Past and Cloudy Future RichardA. Epsteint The title I have given to this short comment is one that does not speak to any great optimism about the future of Law and Economics, and it is incumbent upon me, even in a short essay, to indicate the sources of my uneasiness. When I entered legal academia in 1968, Law and Economics was just getting started as a separate field. The magnitude of the intellectual revolution is hard to recount today because virtually everyone who works in common law subjects is familiar with the now routine exercise of showing why it is, or has to be, the case that this or that common law rule is, or is not, efficient. But the present familiarity should not be read back into the past. In my student days at Oxford be- tween 1964 and 1966, I engaged in an exhaustive study of the common law of contract, property, and torts. I studied legal his- tory and jurisprudence, and learned Roman and international law to boot, all with reference to contract, property, and torts. Yet I cannot recall a single instance in which common law rules were praised for their efficient properties or criticized for their lack thereof. For our normative work, we relied on some intuitive notion of fairness or justice, which seemed to produce on average better economic results than the self-conscious instrumentalism that guides so many judges today. For our descriptive work, we relied on stare decisis and close case readings. To be sure, English academics and judges were less innova- tive than their American counterparts. -

From Olson to Veblen: the Stagflationary Rise of Distributional Coalitions

FROM OLSON TO VEBLEN: THE STAGFLATIONARY RISE OF DISTRIBUTIONAL COALITIONS Jonathan Nitzan Department of Economics McGill University 855 Sherbrooke St. West Montreal, Quebec H3A 2T7 Paper presented at the annual meeting of The History of Economics Society Fairfax, Virginia May 30-June 2, 1992 Contents Introduction 2 1. Distributional Coalitions 2 2. Distributional Coalitions and Macroeconomics: Beginnings 11 3. Industry and Business 19 4. Ownership, Earnings and Capital 25 5. Corporate Finance and the Structural Roots of Inflation and Stagflation 46 6. Toward a Dynamic Theory of Distributional Coalitions and Stagflation 63 References 72 1 Introduction This essay deals with the relationship between stagflation and the process of restructuring. The literature dealing with the interaction of stagnation and inflation is invariably based on some explicit or implicit assumptions about economic structure, but there are very few writings which concentrate specifically on the link between the macroeconomic phenomenon of stagflation and the process of structural change. Of the few who dealt with this issue, we have chosen to focus mainly on two important contributors – Mancur Olson and Thorstein Veblen. The first based his theory on neoclassical principles, attempting to demonstrate their universality across time and place. The second was influenced by the historical school and concentrated specifically on the institutional features of modern capitalism. Despite the fundamental differences in their respective frameworks, both writers arrive at a similar conclusion, namely, that the phenomenon of stagflation is inherent in the dynamic evolution of collective economic action, particularly in the rise and consolidation of ‘distributional coalitions.’ 1. Distributional Coalitions It is perhaps convenient to begin our discussion of institutional dynamics with the general theoretical framework proposed by Olson, first in his 1965 work on The Logic of Collective Action and, later, in his 1982 book on The Rise and Decline of Nations.1 According to Olson (1982, p.