What's Eating My Plant?!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny

insects Article Three Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Orestes guangxiensis, Peruphasma schultei, and Phryganistria guangxiensis (Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny Ke-Ke Xu 1, Qing-Ping Chen 1, Sam Pedro Galilee Ayivi 1 , Jia-Yin Guan 1, Kenneth B. Storey 2, Dan-Na Yu 1,3 and Jia-Yong Zhang 1,3,* 1 College of Chemistry and Life Science, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China; [email protected] (K.-K.X.); [email protected] (Q.-P.C.); [email protected] (S.P.G.A.); [email protected] (J.-Y.G.); [email protected] (D.-N.Y.) 2 Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada; [email protected] 3 Key Lab of Wildlife Biotechnology, Conservation and Utilization of Zhejiang Province, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Simple Summary: Twenty-seven complete mitochondrial genomes of Phasmatodea have been published in the NCBI. To shed light on the intra-ordinal and inter-ordinal relationships among Phas- matodea, more mitochondrial genomes of stick insects are used to explore mitogenome structures and clarify the disputes regarding the phylogenetic relationships among Phasmatodea. We sequence and annotate the first acquired complete mitochondrial genome from the family Pseudophasmati- dae (Peruphasma schultei), the first reported mitochondrial genome from the genus Phryganistria Citation: Xu, K.-K.; Chen, Q.-P.; Ayivi, of Phasmatidae (P. guangxiensis), and the complete mitochondrial genome of Orestes guangxiensis S.P.G.; Guan, J.-Y.; Storey, K.B.; Yu, belonging to the family Heteropterygidae. We analyze the gene composition and the structure D.-N.; Zhang, J.-Y. -

Earwigs from Brazilian Caves, with Notes on the Taxonomic and Nomenclatural Problems of the Dermaptera (Insecta)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 713: 25–52 (2017) Cave-dwelling earwigs of Brazil 25 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.713.15118 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Earwigs from Brazilian caves, with notes on the taxonomic and nomenclatural problems of the Dermaptera (Insecta) Yoshitaka Kamimura1, Rodrigo L. Ferreira2 1 Department of Biology, Keio University, 4-1-1 Hiyoshi, Yokohama 223-8521, Japan 2 Center of Studies in Subterranean Biology, Biology Department, Federal University of Lavras, CEP 37200-000 Lavras (MG), Brazil Corresponding author: Yoshitaka Kamimura ([email protected]) Academic editor: Y. Mutafchiev | Received 17 July 2017 | Accepted 19 September 2017 | Published 2 November 2017 http://zoobank.org/1552B2A9-DC99-4845-92CF-E68920C8427E Citation: Kamimura Y, Ferreira RL (2017) Earwigs from Brazilian caves, with notes on the taxonomic and nomenclatural problems of the Dermaptera (Insecta). ZooKeys 713: 25–52. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.713.15118 Abstract Based on samples collected during surveys of Brazilian cave fauna, seven earwig species are reported: Cy- lindrogaster cavernicola Kamimura, sp. n., Cylindrogaster sp. 1, Cylindrogaster sp. 2, Euborellia janeirensis, Euborellia brasiliensis, Paralabellula dorsalis, and Doru luteipes, as well as four species identified to the (sub) family level. To date, C. cavernicola Kamimura, sp. n. has been recorded only from cave habitats (but near entrances), whereas the other four organisms identified at the species level have also been recorded from non-cave habitats. Wings and female genital structures of Cylindrogaster spp. (Cylindrogastrinae) are examined for the first time. The genital traits, including the gonapophyses of the 8th abdominal segment shorter than those of the 9th segement, and venation of the hind wings of Cylindrogastrinae correspond to those of the members of Diplatyidae and not to Pygidicranidae. -

THE EARWIGS of CALIFORNIA (Order Dermaptera)

BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY VOLUME 20 THE EARWIGS OF CALIFORNIA (Order Dermaptera) BY ROBERT L. LANGSTON and J. A. POWELL UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS THE EARWIGS OF CALIFORNIA (Order Dermaptera) BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY VOLUME 20 THE EARWIGS OF CALIFORNIA (Order Dermaptera) BY ROBERT L. LANGSTON and J. A. POWELL UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON 1975 BULLETIN OF THE CALIFORNIA INSECT SURVEY Advisory Editors: H. V. Daly, J. A. Powell; J. N. Belkin, R. M. Bohart, R. L. Doutt, D. P. Furman, J. D. Pinto, E. I. Schlinger, R. W. Thorp VOLUME 20 Approved for publication September 20,1974 Issued August 15, 1975 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, LTD. LONDON, ENGLAND ISBN 0-520-09524-3 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 74-22940 0 1975 BY THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRINTED BY OFFSET IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONTENTS Introduction .................................................. 1 California fauna ............................................. 1 Biology ................................................... 1 History of establishment and spread of introduced species in California ........ 2 Analysis of data ............................................. 4 Acknowledgments ............................................ 4 Systematic Treatment Classification ............................................... 6 Key to California species ........................................ 6 Anisolabis maritima (Ght5) ................................... -

Common Name: Ringlegged Earwig

Earwigs are beetle-like, short-winged, fast moving insects about ½ inch to 1 inch in length. They are usually dark brown and have a pair of pincher-like appendages at the end of their body. Earwigs have chewing-type mouthparts. They are omnivorous in their feeding habits, eating both plant and animal material. Earwigs may occur as a minor nuisance in gardens or greenhouses where they will nibble on succulent plants such as lettuce. They are also documented to feed on root tubers of radish, potato, sweet potato, and the pods of peanuts, though all feeding is of little consequence. More importantly, earwigs are voracious predators of diverse prey such as caterpillars, aphids, mites, scales, beetle larvae, leafhoppers, and sowbugs. This predatory behavior offsets the small amount of damage done to plants. Earwigs are nocturnal, hiding during the day and roaming at night to find food and water. Because of their nighttime activity, they remain in the soil or under debris during the day. Heavily thatched lawns or mulched flowerbeds are among their preferred daytime habitats. They search for food at night around streetlights, neon lights, lighted windows, or similar locations. While they are chiefly an "outdoor insect," their habit of hiding among plants allows them to be frequently brought into the home. Earwigs rarely warrant suppression and are easily killed by most residual insecticides (even if you didn’t mean to kill the earwigs). Parasitic flies, insect killing fungi as well as cannibalism account for mortality factors. If these pests become a serious nuisance indoors, elimination of hiding places, food material, and moisture sources will reduce the infestation. -

Indiana 4-H Entomology Insect Flash Cards

PURDUE EXTENSION ID-411 Indiana 4-H Entomology Insect Flash Cards Flash cards can be an effective tool to Concentrate follow-up study efforts on help students learn to identify insects the cards that each learner had the most and insect facts. Use the following pages problems with (the “uncertain” and to make flash cards by cutting the “don't know” piles). Make this into horizontal lines, gluing one side, then a game to see who can get the largest folding each in half. It can be “know” pile on the first go-through. especially effective to have a peer educator (student showing the cards who The insects included in these flash cards can see the answers) count to five for are all found in Indiana and used each card. If the learner gets it right, it in the Indiana 4-H/FFA Entomology goes in a "know" pile; if it takes a little Career Development Event. longer, put the card in an "uncertain" pile; and if the learner doesn't know, put the card in a "don't know" pile. Authors: Tim Gibb, Natalie Carroll Editor: Becky Goetz Designer: Jessica Seiler Graduate Student Assistant: Terri Hoctor Common Name – Order Name 1. Alfalfa weevil - Coleoptera 76. Japanese beetle - Coleoptera All Insects 2. American cockroach - Dictyoptera 77. June beetle - Coleoptera 3. Angoumois grain moth - Lepidoptera 78. Katydid - Orthoptera 4. Annual cicada - Homoptera 79. Lace bug - Hemiptera Pictured 5. Antlion - Neuroptera 80. Lady beetle - Coleoptera 6. Aphid - Homoptera 81. Locust leafminer - Coleoptera 7. Apple maggot fly - Diptera 82. Longhorned beetle - Coleoptera 8. -

Field Guide to Predators, Parasies and Pathogens Attacking Insect And

B--60476 7/8/05 1:17 PM Page 1 E-357 7-05 Field Guide to Predators, Parasites and Pathogens Attacking Insect and Mite Pests of Cotton RecognizingRecognizing thethe GoodGood BugsBugs inin CottonCotton by Allen Knutson and John Ruberson B--60476 7/8/05 1:17 PM Page 2 Field Guide to Predators, Parasites and Pathogens Attacking Insect and Mite Pests of Cotton by Allen Knutson and John Ruberson This publication was made possible in part through financial support provided by Cotton Incorporated. Cover photograph by W. Sterling of an immature (nymph) spined soldier bug, a predator of bollworms and other caterpillars in cotton. Authors: Allen Knutson, Professor and Extension Entomologist, Texas Cooperative Extension, Texas A&M Research and Extension Center-Dallas, 17360 Coit Road, Dallas, TX 75252 John Ruberson, Assistant Professor, Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, P.O. Box 748, Tifton, GA 31794. Editor: Edna M. Smith, Communications Specialist, Texas Cooperative Extension. Designer: David N. Lipe, Assistant Graphic Designer and Communications Specialist, Texas Cooperative Extension. Texas Cooperative Extension Edward G. Smith, Director The Texas A&M University System College Station, Texas B--60476 7/8/05 1:17 PM Page 3 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Acknowledgments 4 How to Use This Book 6 Biology of Natural Enemies 7 Use of Natural Enemies 11 Sampling for Natural Enemies 12 Further Reading 15 Table of cotton pests and their natural enemies 16 Pesticides and Natural Enemies 20 Table of chemical classes and cotton insecticides 23 Predators -

Isoptera Through Hemiptera

Introduction to Applied Entomology, University of Illinois The Insect Orders II: Isoptera through Hemiptera This lecture spans the following orders: Isoptera -- the termites Dermaptera -- the earwigs Embioptera* -- the webspinners Plecoptera -- the stoneflies Zoraptera* -- the zorapterans Psocoptera -- the psocids (booklice and barklice) Phthiraptera -- the lice Hemiptera o Suborder Heteroptera -- the true bugs o “Suborder” Homoptera -- cicadas, hoppers, psyllids, whiteflies, aphids, and scales To cover this range of orders, lecture 6 devotes only a little time to each. In addition, the Embioptera and Zoraptera are not discussed at all in this course. Isoptera: The termites Iso = equal; ptera = wing; fore and hind wings are nearly identical. Web sites to check ... Isoptera on the NCSU General Entomology page Isoptera on Wikipedia Termite control, University of Kentucky Description and identification: Adults: Mouthparts: Chewing Size: Workers and soldiers 6 - 13 mm (1/4- to ½-inch); queens much larger Wings: 4 in reproductives, lost after dispersal flight. Wings are equal in size. Other castes are wingless. Distinguishing characteristics: Head is heavily sclerotized; other body regions are soft. Castes include workers, soldiers, reproductives. Soldiers have enlarged or specially modified mandibles. Introduction to Applied Entomology, University of Illinois Immatures (called nymphs): Similar to adults (except for the reproductives). Metamorphosis: Gradual; nymphs resemble adults and share the same habitat. In those with wings, external wing pads develop as nymphs mature. Habitat: Nests (colonies) in wood or soil; feed directly on wood, wood products, and similar high- cellulose materials. Pest or Beneficial Status: Severe pests of wood and related products; key in breakdown of plant debris. The eastern subterranean termite is most troublesome in the eastern United States. -

Theodore J. Cohn Research Successful

METALEPTEAMETALEPTEA THE NEWSLETTER OF THE ORTHOPTERISTS’ SOCIETY President’s Message [1] PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE By MICHAEL SAMWAYS President he 11th Congress of bership and [2] INTRODUCING OUR NEW Orthopterology in Kun- Occasional EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ming, China and orga- Publications. nized by Professor Long He also start- [3] SOCIETY NEWS Zhang, was the largest ed to move TT yet, and immensely the Society [3] The Theodore J. Cohn Research successful. There were many stimu- into a truly Fund: A call for applications lating sessions and a great exchange international [4] Symposium Report by MATAN of ideas. Already, this has led to some organization, SHELOMI fruitful new liaisons among several of especially the delegates. The outcomes of some through the [5] OS GRANT REPORTS of these new interactions we will no activity of the Regional Representa- doubt see unfold at our next Congress tives. Of course, Chuck is still an [5] Searching for a hope: An expedi- in Brazil in 2016. active member of the Society and tion in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest continues to give advice on matters by JULIANA CHAMORRO-RENGIFO The Ted Cohn Research Fund of organization. We wish Chuck all The late Ted Cohn was not only a the best in devoting his time to seeing [6] Microbial community structure dedicated Orthopterist, but also an his university Faculty on its way as reflects population genetic struc- extraordinarily dedicated member of its Dean. Thanks, Chuck, for all you ture in an ecologically divergent grasshopper by TYLER JAY RASZICK our Society. As well as being a Past have done for the Society! President twice, he personally saw [7] CONTRIBUTED ARTICLES that many young researchers were Welcome to our new Executive endowed with funds to undertake Director [7] Scattered Recollections: The exciting new research projects. -

Increasing Beneficial Insects in Row Crops and Gardens

■ ,VVXHG LQ IXUWKHUDQFH RI WKH &RRSHUDWLYH ([WHQVLRQ :RUN$FWV RI 0D\ DQG -XQH LQ FRRSHUDWLRQ ZLWK WKH 8QLWHG 6WDWHV 'HSDUWPHQWRI$JULFXOWXUH 'LUHFWRU&RRSHUDWLYH([WHQVLRQ8QLYHUVLW\RI0LVVRXUL&ROXPELD02 ■DQHTXDORSSRUWXQLW\$'$LQVWLWXWLRQ■■H[WHQVLRQPLVVRXULHGX AGRICULTURE Increasing Beneficial Insects in Row Crops and Gardens eneficial insects can be useful in and coincide with times beneficial integrated pest management of insects are least active. Lowering the Steps for attracting Brow crops and gardens. They incidence of drift reduces the amount beneficial insects are a form of biological control in that of insecticide applied to flowering • Provide large, concentrated plantings their activity reduces the activity of plants, which in turn reduces the of flowering plants because many certain pest species. For many pest chance of killing beneficial insects. beneficial insects also feed on plant insects, the most important check on nectar. their populations is the activity of beneficial insects. If populations of Less than 5 percent • Provide water if possible. beneficial insects are allowed to of all insects are pests. • Place blooming flowers in sunshine and increase throughout the growing in locations with minimal wind. season, they can reduce pest • Maintain diversity in varieties, height, populations of moths, aphids, mites Some insects, such as honeybees and color and blooming period of plants. and bugs by 20 to 40 percent. butterflies, are considered beneficial because of the important role they • Use as little pesticide as possible. play in plant pollination. The insects Insects are always active in the described in this guide are considered garden, and the vast majority beneficial because they feed on other predacious. Adult beetles have two can be classified as beneficial. -

The Order Dermaptera (Earwigs) in Florida and the United States P

Left Labidura riparia (male); Right - Euborellia annulipes (female). The Order Dermaptera (Earwigs) in Florida and the United States P. M. Choate - (modified from Hoffman, 1987) Six families of earwigs (Dermaptera) occur in Florida and the US. These insects are easily introduced in plant materials. New Florida records are based on FSCA* specimens intercepted on plants inspected at Miami. 1. Family Pygidicranidae Pyragropsis buscki (Caudell) FL 2. Family Carcinophoridae Anisolabis maritima (Bonelli) widespread on sea coasts Euborellia annulipes (Lucas) southeast US, widespread Euborellia ambigua (Borelli) FL Euborellia annulata (Lucas) FL (Miami) (identified as Euborellia stali (Dohrn) Euborellia caraibea Hebard FL Euborellia cincticollis (Gerstaecker) AZ, CA Euborellia femoralis (Dohrn) AZ, CA Gonolabis azteca Dohrn (FL) - reported in Arnett (1993) 3. Family Labiduridae (1 cosmopolitan species) Labidura riparia (Pallas) southeastern US, FL, AZ, CA, TX 4. Family Labiidae s. f. Spongiphorinae Vostox brunneipennis (Aud. Serv.) eastern US, TX, OK Vostox excavatus Nutting and Gurney AZ, NM Vostox apicedentatus (Candell) AZ, CA, NM, TX s. f. Labiinae Labia minor (L.) widespread Labia curvicauda (Motsch.) FL *Abbreviation(s): FSCA - Florida State Collection of Arthropods, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, FL. Page 1 of 8 Labia rehni Hebard FL Marava arachidis Yersin AZ, CA, TX, NJ, FL Marava pulchella (Aud.-Serv.) SE US, TX 5. Family Chelisochidae (introduced into Pac. Northwest, California, and Florida) Chelisoches morio (Fabricius) CA, FL (Dade Co., Palm Beach Co.) FSCA. 6. Family Forficulidae Doru davisi Rehn and Hebard FL Doru aculeatum (Scudder) eastern US, Ontario D. taeniatum (Dohrn) southeastern US, AZ, CA, TX Forficula auricularia L. widespread (incl. FL) - European earwig **The following 2 species are previously unrecorded from USA and represent new records yet to be published. -

Introduction to Entomology

® EXTENSION Know how. Know now. EC1588 Introduction to Entomology James A. Kalisch, Entomology Extension Associate Ivy Orellana, Extension Assistant Extension is a Division of the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln cooperating with the Counties and the United States Department of Agriculture. University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension educational programs abide with the nondiscrimination policies of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and the United States Department of Agriculture. © 2014, The Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska on behalf of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension. All rights reserved. Introduction to Entomology James A. Kalisch, Entomology Extension Associate Ivy Orellana, Extension Assistant Insects and mites are among the known to exist. They have three the insects . Within the class Insecta, most numerous animals on earth. In a characteristics in common — a seg- various characteristics are used to typical midsummer landscape and gar- mented body, jointed legs, and an group insects into orders (Table 1). den, there are approximately a thou- exoskeleton. The Arthropoda phylum These characteristics are easily visible sand insects in addition to mites and is divided into classes, and some com- and do not require a microscope; for spiders! The goals of this publication is mon names of each class includes example, mouthparts, wings, and type to introduce the science of entomology the crustaceans, centipedes, milli- of metamorphosis are all identifying and insect identification to those who pedes, spiders, ticks and mites, and characteristics. are active in outdoor landscapes or natural settings. Insects play a valuable role in our Table 1. The following table describes the common names associated with natural world. -

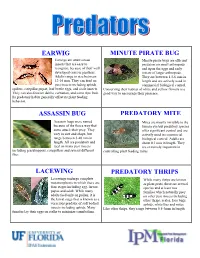

Earwig Assassin Bug Minute Pirate Bug Predatory Mite Lacewing Predatory Thrips

MINUTE PIRATE BUG EARWIG Earwigs are omnivorous Minute pirate bugs are efficient insects that are easy to predators on small arthropods recognize because of their well and upon the eggs and early developed cerci or pinchers.. instars of larger arthropods. Adults range in size between They are between 1.5-6 mm in 12-16 mm. They can feed on length and are actively used in pest insects including aphids, commercial biological control. spiders, catepillar pupae, leaf beetle eggs, and scale insects. Conserving their habitat of white and yellow flowers is a They can also feed on dahlia, carnation, and some ripe fruit. good way to encourage their presence. Its predatory habits generally offset its plant feeding behavior. ASSASSIN BUG PREDATORY MITE Assassin bugs were named Mites are mostly invisible to the because of the fierce way that human eye but predatory species some attack their prey. They offer significant control and are vary in size and shape, but actively used in commercial range between 3-40 mm in biological control. Adults are length. All are predatory and about 0.1 mm in length. They feed on many pest insects are extremely important in including grasshoppers, caterpillars and several different controlling plant feeding mites. flies. LACEWING PREDATORY THRIPS Lacewings undergo complete While many thrips are known metamorphosis in which there are as plant pests, there are several four stages including egg, larvae, species and at least two pupae and adult. While many families which naturally prey adults feed only on pollen, it is on other pest insects including the larval stage that is known as a other thrips, scales, lace bugs, voracious predator of soft bodied aphids, whiteflies and mites.