Introduction to Entomology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny

insects Article Three Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Orestes guangxiensis, Peruphasma schultei, and Phryganistria guangxiensis (Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny Ke-Ke Xu 1, Qing-Ping Chen 1, Sam Pedro Galilee Ayivi 1 , Jia-Yin Guan 1, Kenneth B. Storey 2, Dan-Na Yu 1,3 and Jia-Yong Zhang 1,3,* 1 College of Chemistry and Life Science, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China; [email protected] (K.-K.X.); [email protected] (Q.-P.C.); [email protected] (S.P.G.A.); [email protected] (J.-Y.G.); [email protected] (D.-N.Y.) 2 Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada; [email protected] 3 Key Lab of Wildlife Biotechnology, Conservation and Utilization of Zhejiang Province, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Simple Summary: Twenty-seven complete mitochondrial genomes of Phasmatodea have been published in the NCBI. To shed light on the intra-ordinal and inter-ordinal relationships among Phas- matodea, more mitochondrial genomes of stick insects are used to explore mitogenome structures and clarify the disputes regarding the phylogenetic relationships among Phasmatodea. We sequence and annotate the first acquired complete mitochondrial genome from the family Pseudophasmati- dae (Peruphasma schultei), the first reported mitochondrial genome from the genus Phryganistria Citation: Xu, K.-K.; Chen, Q.-P.; Ayivi, of Phasmatidae (P. guangxiensis), and the complete mitochondrial genome of Orestes guangxiensis S.P.G.; Guan, J.-Y.; Storey, K.B.; Yu, belonging to the family Heteropterygidae. We analyze the gene composition and the structure D.-N.; Zhang, J.-Y. -

'Tqiltfl Gn Qrahdt 'T.T+Ttfl - 3Cg U\To

qlc{l}s'fts d'r rL'ftl-tct oilc{-sfl 'tqiltfl gN qRaHdt 't.t+ttfl - 3Cg U\tO r5rfr I ff EEtf,IlFfrt u f Effltfy lt|.[b.ft rrti uQqarcj.e{ tI[ troa C tJdderor il.&a, ?ooc scrrr u (r) o{l Page No.-1 f,iar- o{l qRqa t{ls (irL{l.oer .rdt.rfl fd.atclotL ct.3 \/oL/?oog, crr'oc/oc/?o1'e{ ' q2t {lrlSl-loeoog-3 3 tt3 sY-r,rtaAqttjil.e r'ti' sct ufdtrr{lat s}tis "i' q"cf otg r{. - ? o q, d[. O S,/o Y,/ ? o t q D' ) {./ ?U / 3 . 3,/ Y 3 o t Uq'o / t Ul{|'qtq'( r,tell uqtQ.a secrt:{ l,tta. E } {[d.ft r,t[Qstt r't[0'G.qq"t 5a{ - u dact.{ +qai m&e sa.rt"t ortqaf riLl}.sA.t Stualsr G.A.D.) ql "[L sl{ rtat i.qn sr.rt:{i r,tO.a E. qi. at. ot,/ott/?o?o"t qQ(Adl uutgl rtuaa sacrtul r,rtda D. ar{trrt - te,/oq,/?o?o ql.cft)s'fts o't A"{l{a ou"s{l 't.til{t 5G. qRqHdl "t.{il{-3CS YttO ,ffiu )aftgf't.t. oesgo Qet c?Y .ra<,ig daaafl sldn <.r+u{ gR qG.oRdt dqut{-3e9 u\to Page No.-2 {r[dd ui uRqqcj.E ot/or{/?o?o r,rqstrQlsr 93?gt [d.ot.t ULctL dtGt? 1. {+urq {+errua, GEeit, stqf ui gerf"0 ficra] ox {+€rtat u[0.stflr,i. -

ENTOMOLOGY 322 LABS 13 & 14 Insect Mouthparts

ENTOMOLOGY 322 LABS 13 & 14 Insect Mouthparts The diversity in insect mouthparts may explain in part why insects are the predominant form of multicellular life on earth (Bernays, 1991). Insects, in one form or another, consume essentially every type of food on the planet, including most terrestrial invertebrates, plant leaves, pollen, fungi, fungal spores, plant fluids (both xylem and phloem), vertebrate blood, detritus, and fecal matter. Mouthparts are often modified for other functions as well, including grooming, fighting, defense, courtship, mating, and egg manipulation. This tremendous morphological diversity can tend to obscure the essential appendiculate nature of insect mouthparts. In the following lab exercises we will track the evolutionary history of insect mouthparts by comparing the mouthparts of a generalized insect (the cricket you studied in the last lab) to a variety of other arthropods, and to the mouthparts of some highly modified insects, such as bees, butterflies, and cicadas. As mentioned above, the composite nature of the arthropod head has lead to considerable debate as to the true homologies among head segments across the arthropod classes. Table 13.1 is presented below to help provide a framework for examining the mouthparts of arthropods as a whole. 1. Obtain a specimen of a horseshoe crab (Merostoma: Limulus), one of the few extant, primitively marine Chelicerata. From dorsal view, note that the body is divided into two tagmata, the anterior Figure 13.1 (Brusca & Brusca, 1990) prosoma (cephalothorax) and the posterior opisthosoma (abdomen) with a caudal spine (telson) at its end (Fig. 13.1). In ventral view, note that all locomotory and feeding appendages are located on the prosoma and that all except the last are similar in shape and terminate in pincers. -

Alfred Russel Wallace and the Darwinian Species Concept

Gayana 73(2): Suplemento, 2009 ISSN 0717-652X ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE AND THE Darwinian SPECIES CONCEPT: HIS paper ON THE swallowtail BUTTERFLIES (PAPILIONIDAE) OF 1865 ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE Y EL concepto darwiniano DE ESPECIE: SU TRABAJO DE 1865 SOBRE MARIPOSAS papilio (PAPILIONIDAE) Jam ES MA LLET 1 Galton Laboratory, Department of Biology, University College London, 4 Stephenson Way, London UK, NW1 2HE E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Soon after his return from the Malay Archipelago, Alfred Russel Wallace published one of his most significant papers. The paper used butterflies of the family Papilionidae as a model system for testing evolutionary hypotheses, and included a revision of the Papilionidae of the region, as well as the description of some 20 new species. Wallace argued that the Papilionidae were the most advanced butterflies, against some of his colleagues such as Bates and Trimen who had claimed that the Nymphalidae were more advanced because of their possession of vestigial forelegs. In a very important section, Wallace laid out what is perhaps the clearest Darwinist definition of the differences between species, geographic subspecies, and local ‘varieties.’ He also discussed the relationship of these taxonomic categories to what is now termed ‘reproductive isolation.’ While accepting reproductive isolation as a cause of species, he rejected it as a definition. Instead, species were recognized as forms that overlap spatially and lack intermediates. However, this morphological distinctness argument breaks down for discrete polymorphisms, and Wallace clearly emphasised the conspecificity of non-mimetic males and female Batesian mimetic morphs in Papilio polytes, and also in P. -

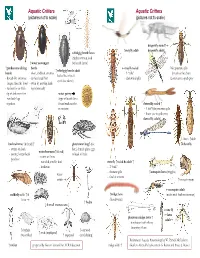

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Is Ellipura Monophyletic? a Combined Analysis of Basal Hexapod

ARTICLE IN PRESS Organisms, Diversity & Evolution 4 (2004) 319–340 www.elsevier.de/ode Is Ellipura monophyletic? A combined analysis of basal hexapod relationships with emphasis on the origin of insects Gonzalo Giribeta,Ã, Gregory D.Edgecombe b, James M.Carpenter c, Cyrille A.D’Haese d, Ward C.Wheeler c aDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 16 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA bAustralian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia cDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA dFRE 2695 CNRS, De´partement Syste´matique et Evolution, Muse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle, 45 rue Buffon, F-75005 Paris, France Received 27 February 2004; accepted 18 May 2004 Abstract Hexapoda includes 33 commonly recognized orders, most of them insects.Ongoing controversy concerns the grouping of Protura and Collembola as a taxon Ellipura, the monophyly of Diplura, a single or multiple origins of entognathy, and the monophyly or paraphyly of the silverfish (Lepidotrichidae and Zygentoma s.s.) with respect to other dicondylous insects.Here we analyze relationships among basal hexapod orders via a cladistic analysis of sequence data for five molecular markers and 189 morphological characters in a simultaneous analysis framework using myriapod and crustacean outgroups.Using a sensitivity analysis approach and testing for stability, the most congruent parameters resolve Tricholepidion as sister group to the remaining Dicondylia, whereas most suboptimal parameter sets group Tricholepidion with Zygentoma.Stable hypotheses include the monophyly of Diplura, and a sister group relationship between Diplura and Protura, contradicting the Ellipura hypothesis.Hexapod monophyly is contradicted by an alliance between Collembola, Crustacea and Ectognatha (i.e., exclusive of Diplura and Protura) in molecular and combined analyses. -

What's Eating You? Chiggers

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS WITH THE ENVIRONMENT What’s Eating You? Chiggers Dirk M. Elston, MD higger is the common name for the 6-legged larval form of a trombiculid mite. The larvae C suck blood and tissue fluid and may feed on a variety of animal hosts including birds, reptiles, and small mammals. The mite is fairly indiscrimi- nate; human hosts will suffice when the usual host is unavailable. Chiggers also may be referred to as harvest bugs, harvest lice, harvest mites, jiggers, and redbugs (Figure 1). The term jigger also is used for the burrowing chigoe flea, Tunga penetrans. Chiggers belong to the family Trombiculidae, order Acari, class Arachnida; many species exist. Trombiculid mites are oviparous; they deposit their eggs on leaves, blades of grass, or the open ground. After several days, the egg case opens, but the mite remains in a quiescent prelarval stage. Figure 1. Chigger mite. After this prelarval stage, the small 6-legged larvae become active and search for a host. During this larval 6-legged stage, the mite typically is found attaches at sites of constriction caused by clothing, attached to the host. After a prolonged meal, the where its forward progress has been impeded. Penile larvae drop off. Then they mature through the and scrotal lesions are not uncommon and may be 8-legged free-living nymph and adult stages. mistaken for scabies infestation. Seasonal penile Chiggers can be found throughout the world. In swelling, pruritus, and dysuria in children is referred the United States, they are particularly abundant in to as summer penile syndrome. -

Annotated Checklist of the Diplura (Hexapoda: Entognatha) of California

Zootaxa 3780 (2): 297–322 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3780.2.5 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DEF59FEA-C1C1-4AC6-9BB0-66E2DE694DFA Annotated Checklist of the Diplura (Hexapoda: Entognatha) of California G.O. GRAENING1, YANA SHCHERBANYUK2 & MARYAM ARGHANDIWAL3 Department of Biological Sciences, California State University, Sacramento 6000 J Street, Sacramento, CA 95819-6077. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The first checklist of California dipluran taxa is presented with annotations. New state and county records are reported, as well as new taxa in the process of being described. California has a remarkable dipluran fauna with about 8% of global richness. California hosts 63 species in 5 families, with 51 of those species endemic to the State, and half of these endemics limited to single locales. The genera Nanojapyx, Hecajapyx, and Holjapyx are all primarily restricted to California. Two species are understood to be exotic, and six dubious taxa are removed from the State checklist. Counties in the central Coastal Ranges have the highest diversity of diplurans; this may indicate sampling bias. Caves and mines harbor unique and endemic dipluran species, and subterranean habitats should be better inventoried. Only four California taxa exhibit obvious troglomorphy and may be true cave obligates. In general, the North American dipluran fauna is still under-inven- toried. Since many taxa are morphologically uniform but genetically diverse, genetic analyses should be incorporated into future taxonomic descriptions. -

Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Credit Ours: (2+1=3) THEORY Part – I 1

Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Ag. Ento. 3.1 Fundamentals of Entomology Credit ours: (2+1=3) THEORY Part – I 1. History of Entomology in India. 2. Factors for insect‘s abundance. Major points related to dominance of Insecta in Animal kingdom. 3. Classification of phylum Arthropoda up to classes. Relationship of class Insecta with other classes of Arthropoda. Harmful and useful insects. Part – II 4. Morphology: Structure and functions of insect cuticle, moulting and body segmentation. 5. Structure of Head, thorax and abdomen. 6. Structure and modifications of insect antennae 7. Structure and modifications of insect mouth parts 8. Structure and modifications of insect legs, wing venation, modifications and wing coupling apparatus. 9. Metamorphosis and diapause in insects. Types of larvae and pupae. Part – III 10. Structure of male and female genital organs 11. Structure and functions of digestive system 12. Excretory system 13. Circulatory system 14. Respiratory system 15. Nervous system, secretary (Endocrine) and Major sensory organs 16. Reproductive systems in insects. Types of reproduction in insects. MID TERM EXAMINATION Part – IV 17. Systematics: Taxonomy –importance, history and development and binomial nomenclature. 18. Definitions of Biotype, Sub-species, Species, Genus, Family and Order. Classification of class Insecta up to Orders. Major characteristics of orders. Basic groups of present day insects with special emphasis to orders and families of Agricultural importance like 19. Orthoptera: Acrididae, Tettigonidae, Gryllidae, Gryllotalpidae; 20. Dictyoptera: Mantidae, Blattidae; Odonata; Neuroptera: Chrysopidae; 21. Isoptera: Termitidae; Thysanoptera: Thripidae; 22. Hemiptera: Pentatomidae, Coreidae, Cimicidae, Pyrrhocoridae, Lygaeidae, Cicadellidae, Delphacidae, Aphididae, Coccidae, Lophophidae, Aleurodidae, Pseudococcidae; 23. Lepidoptera: Pieridae, Papiloinidae, Noctuidae, Sphingidae, Pyralidae, Gelechiidae, Arctiidae, Saturnidae, Bombycidae; 24. -

Zoology 325 General Entomology – Lecture Department of Biological Sciences University of Tennessee at Martin Fall 2013

Zoology 325 General Entomology – lecture Department of Biological Sciences University of Tennessee at Martin Fall 2013 Instructor: Kevin M. Pitz, Ph.D. Office: 308 Brehm Hall Phone: (731) 881-7173 (office); (731) 587-8418 (home, before 7:00pm only) Email: [email protected] Office hours: I am generally in my office or in Brehm Hall when not in class or at lunch. I take lunch from 11:00am-noon every day. I am in class from 8am-5pm on Monday, and from 8:00am-11:00am + 2:00pm-3:30pm on T/Th. I have no classes on Wednesday and Friday. My door is always open when I am available, and you are encouraged to stop by any time I am in if you need something. You can guarantee I will be there if we schedule an appointment. Text (required): The Insects: an Outline of Entomology. 4th Edition. P.J. Gullan and P.S. Cranston. Course Description: (4) A study of the biology, ecology, morphology, natural history, and taxonomy of insects. Emphasis on positive and negative human-insect interactions and identification of local insect fauna. This course requires field work involving physical activity. Three one-hour lectures and one three-hour lab (or equivalent). Prereq: BIOL 130-140 with grades of C or better. (Modified from course catalogue) Prerequisites: BIOL 130-140 Course Objectives: Familiarity with the following: – Insect morphology, both internal and external – Insect physiology and development – Insect natural history and ecology – Positive and negative human-insect interactions – Basic insect management practices On top of the academic objectives associated with course material, I expect students to hone skills in critical reading, writing, and thinking. -

Investigating the Functional Morphology of Genitalia During Copulation in the Grasshopper Melanoplus Rotundipennis (Scudder, 1878) Via Correlative Microscopy

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 278:334–359 (2017) Investigating the Functional Morphology of Genitalia During Copulation in the Grasshopper Melanoplus rotundipennis (Scudder, 1878) via Correlative Microscopy Derek A. Woller* and Hojun Song Department of Entomology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas ABSTRACT We investigated probable functions of the males, in terms of the number of components interacting genitalic components of a male and a involved in copulation and reproduction (Eberhard, female of the flightless grasshopper species Melanoplus 1985; Arnqvist, 1997; Eberhard, 2010). This rela- rotundipennis (Scudder, 1878) (frozen rapidly during tive complexity has often masked our ability to copulation) via correlative microscopy; in this case, by understand functional genitalic morphology, partic- synergizing micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) with digital single lens reflex camera photography with ularly during the copulation process. This process focal stacking, and scanning electron microscopy. To is difficult to examine intensely due to its often- assign probable functions, we combined imaging results hidden nature (internal components shielded from with observations of live and museum specimens, and view by external components) and because it is function hypotheses from previous studies, the majority often easily interrupted by active observation, but of which focused on museum specimens with few inves- some studies investigating function have manipu- tigating hypotheses in a physical framework of copula- lated genitalia as a way around such issues tion. For both sexes, detailed descriptions are given for (Briceno~ and Eberhard, 2009; Grieshop and Polak, each of the observed genitalic and other reproductive 2012; Dougherty et al., 2015). Adding further com- system components, the majority of which are involved in copulation, and we assigned probable functions to plexity to understanding function, several studies these latter components. -

A New Fishfly Species (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae) from Eocene Baltic Amber

Palaeoentomology 003 (2): 188–195 ISSN 2624-2826 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pe/ PALAEOENTOMOLOGY Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2624-2834 (online edition) PE https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.3.2.8 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:20A34D9A-DC69-453E-9662-0A8FAFA25677 A new fishfly species (Megaloptera: Corydalidae: Chauliodinae) from Eocene Baltic amber XINGYUE LIU1, * & JÖRG ANSORGE2 1College of Life Science and Technology, Hubei Engineering University, Xiaogan 432000, China �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9168-0659 2Institute of Geography and Geology, University of Greifswald, Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahnstraße 17a, D-17487 Greifswald, Germany �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1284-6893 *Corresponding author. �[email protected] Abstract and Sialidae (alderflies). Species of Megaloptera have worldwide distribution, but most of them occur mainly in The fossil record of Megaloptera (Insecta: Holometabola: subtropical and warm temperate regions, e.g., the Oriental, Neuropterida) is very limited. Both megalopteran families, i.e., Corydalidae and Sialidae, have been found in the Eocene Neotropical, and Australian Regions (Yang & Liu, 2010; Baltic amber, comprising two named species in one genus Liu et al., 2012, 2015a). The phylogeny and biogeography of Corydalidae (Chauliodinae) and four named species in of extant Megaloptera have been intensively studied in two genera of Sialidae. Here we report a new species of Liu et al. (2012, 2015a, b, 2016) and Contreras-Ramos Chauliodinae from the Baltic amber, namely Nigronia (2011). prussia sp. nov.. The new species possesses a spotted hind Compared with the other two orders of Neuropterida wing with broad band-like marking, a well-developed stem (Raphidioptera and Neuroptera), the fossil record of of hind wing MA subdistally with a short crossvein to MP, a Megaloptera is considerably scarce.