Morphologic and Biologic Characteristics of the Canine Cutaneous Histiocytoma'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry for Canine Cutaneous Round Cell Tumours — Retrospective Analysis of 60 Cases

FOLIA HISTOCHEMICA ORIGINAL PAPER ET CYTOBIOLOGICA Vol. 57, No. 3, 2019 pp. 146–154 Diagnostic immunohistochemistry for canine cutaneous round cell tumours — retrospective analysis of 60 cases Katarzyna Pazdzior-Czapula, Mateusz Mikiewicz, Michal Gesek, Cezary Zwolinski, Iwona Otrocka-Domagala Department of Pathological Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Olsztyn, Poland Abstract Introduction. Canine cutaneous round cell tumours (CCRCTs) include various benign and malignant neoplastic processes. Due to their similar morphology, the diagnosis of CCRCTs based on histopathological examination alone can be challenging, often necessitating ancillary immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. This study presents a retrospective analysis of CCRCTs. Materials and methods. This study includes 60 cases of CCRCTs, including 55 solitary and 5 multiple tumours, evaluated immunohistochemically using a basic antibody panel (MHCII, CD18, Iba1, CD3, CD79a, CD20 and mast cell tryptase) and, when appropriate, extended antibody panel (vimentin, desmin, a-SMA, S-100, melan-A and pan-keratin). Additionally, histochemical stainings (May-Grünwald-Giemsa and methyl green pyronine) were performed. Results. IHC analysis using a basic antibody panel revealed 27 cases of histiocytoma, one case of histiocytic sarcoma, 18 cases of cutaneous lymphoma of either T-cell (CD3+) or B-cell (CD79a+) origin, 5 cases of plas- macytoma, and 4 cases of mast cell tumours. The extended antibody panel revealed 2 cases of alveolar rhabdo- myosarcoma, 2 cases of amelanotic melanoma, and one case of glomus tumour. Conclusions. Both canine cutaneous histiocytoma and cutaneous lymphoma should be considered at the beginning of differential diagnosis for CCRCTs. While most poorly differentiated CCRCTs can be diagnosed immunohis- tochemically using 1–4 basic antibodies, some require a broad antibody panel, including mesenchymal, epithelial, myogenic, and melanocytic markers. -

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans and Dermatofibroma: Dermal Dendrocytomas? a Ultrastructural Study

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans and Dermatofibroma: Dermal Dendrocytomas? A Ultrastructural Study Hugo Dominguez-Malagon, M.D., Ana Maria Cano-Valdez, M.D. Department of Pathology, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Mexico. ABSTRACT population of plump spindled cells devoid of cell processes, these cells contained intracytoplasmic lipid droplets and rare Dermatofibroma (DF) and Dermatofibrosarcoma subplasmalemmal densities but lacked MVB. Protuberans (DFSP) are dermal tumors whose histogenesis has not been well defined to date. The differential diagnosis in most With the ultrastructural characteristics and the constant cases is established in routine H/E sections and may be confirmed expression of CD34 in DFSP, a probable origin in dermal by immunohistochemistry; however there are atypical variants dendrocytes is postulated. The histogenesis of DF remains of DF with less clear histological differences and non-conclusive obscure. immunohistochemical results. In such cases electron microscopy studies may be useful to establish the diagnosis. INTRODUCTION In the present paper the ultrastructural characteristics of 38 The histogenesis or differentiation of cases of DFSP and 10 cases of DF are described in detail, the Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans (DFSP) and objective was to identify some features potentially useful for Dermatofibroma (DF) is controversial in the literature. For differential diagnosis, and to identify the possible histogenesis of DFSP diverse origins such as fibroblastic,1 fibro-histiocytic2 both neoplasms. Schwannian,3 myofibroblastic,4 perineurial,5,6 and endoneurial (7) have been postulated. DFSP in all cases was formed by stellate or spindled cells with long, slender, ramified cell processes joined by primitive junctions, Regarding DF, most authors are in agreement of a subplasmalemmal densities were frequently seen in the processes. -

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans of the Parotid Gland -A Case Report

The Korean Journal of Pathology 2004; 38: 276-9 Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans of the Parotid Gland -A Case Report - Ok-Jun Lee∙David Y. Pi∙ Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) typically presents during the early or mid-adult life, Daniel H. Jo∙Kyung-Ja Cho and the most common site of origin is the skin on the trunk and proximal extremities. DFSP of Sang Yoon Kim1∙Jae Y. Ro the parotid gland is extremely rare and only one case has been reported in the literature. We present here a case of a 30-year-old woman with DFSP occurring in the parotid gland, and we Departments of Pathology and discuss the differential diagnosis. The patient is alive and doing well one year after her operation. 1Otolaryngology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea Received : January 27, 2004 Accepted : July 5, 2004 Corresponding Author Jae Y. Ro, M.D. Department of Pathology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, 388-1 Pungnap-dong, Songpa-gu, Seoul 138-736, Korea Tel: 02-3010-4550 Fax: 02-472-7898 E-mail: [email protected] Key Words : Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans-Parotid Gland Epithelial tumors make up the majority of salivary gland neo- CASE REPORT plasms, while mesenchymal tumors of this organ are uncommon. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) of the salivary gland A 30-year-old woman came to the Otolaryngology Clinic at is exremely rare and only one case has been reported in the parotid the Asan Medical Center with a 2-year history of a slowly enlarg- gland.1 ing mass inferior to the left angle of the mandible. -

Epithelioid Fibrous Histiocytoma

Modern Pathology (2018) 31, 753–762 © 2018 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/18 $32.00 753 Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: molecular characterization of ALK fusion partners in 23 cases Brendan C Dickson1,2,3, David Swanson1,3, George S Charames1,2,3, Christopher DM Fletcher4,5 and Jason L Hornick4,5 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; 2Department of Pathobiology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; 3Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; 4Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA and 5Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma is a rare and distinctive cutaneous neoplasm. Most cases harbor ALK rearrangement and show ALK overexpression, which distinguish this neoplasm from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma and variants. SQSTM1 and VCL have previously been shown to partner with ALK in one case each of epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. The purpose of this study was to examine a large cohort of epithelioid fibrous histiocytomas by next-generation sequencing to characterize the nature and prevalence of ALK fusion partners. A retrospective archival review was performed to identify cases of epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma (2012–2016). Immunohistochemistry was performed to confirm ALK expression. Targeted next- generation sequencing was applied on RNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue to identify the fusion partners. Twenty-three cases fulfilled inclusion criteria. The mean patient age was 39 years (range, 8– 74), there was no sex predilection, and 475% of cases involved the lower extremities. The most common gene fusions were SQSTM1-ALK (N = 12; 52%) and VCL-ALK (N = 7; 30%); the other four cases harbored novel fusion partners (DCTN1, ETV6, PPFIBP1, and SPECC1L). -

About Soft Tissue Sarcoma Overview and Types

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Soft Tissue Sarcoma Overview and Types If you've been diagnosed with soft tissue sarcoma or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Is a Soft Tissue Sarcoma? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of soft tissue sarcoma and deaths in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics for Soft Tissue Sarcomas ● What's New in Soft Tissue Sarcoma Research? What Is a Soft Tissue Sarcoma? Cancer starts when cells start to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer and can spread to other areas. To learn more about how cancers start and spread, see What Is Cancer?1 There are many types of soft tissue tumors, and not all of them are cancerous. Many benign tumors are found in soft tissues. The word benign means they're not cancer. These tumors can't spread to other parts of the body. Some soft tissue tumors behave 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 in ways between a cancer and a non-cancer. These are called intermediate soft tissue tumors. When the word sarcoma is part of the name of a disease, it means the tumor is malignant (cancer).A sarcoma is a type of cancer that starts in tissues like bone or muscle. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas are the main types of sarcoma. Soft tissue sarcomas can develop in soft tissues like fat, muscle, nerves, fibrous tissues, blood vessels, or deep skin tissues. -

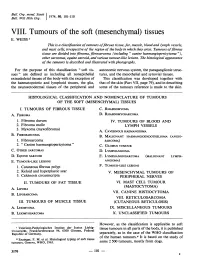

Mesenchymal) Tissues E

Bull. Org. mond. San 11974,) 50, 101-110 Bull. Wid Hith Org.j VIII. Tumours of the soft (mesenchymal) tissues E. WEISS 1 This is a classification oftumours offibrous tissue, fat, muscle, blood and lymph vessels, and mast cells, irrespective of the region of the body in which they arise. Tumours offibrous tissue are divided into fibroma, fibrosarcoma (including " canine haemangiopericytoma "), other sarcomas, equine sarcoid, and various tumour-like lesions. The histological appearance of the tamours is described and illustrated with photographs. For the purpose of this classification " soft tis- autonomic nervous system, the paraganglionic struc- sues" are defined as including all nonepithelial tures, and the mesothelial and synovial tissues. extraskeletal tissues of the body with the exception of This classification was developed together with the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, the glia, that of the skin (Part VII, page 79), and in describing the neuroectodermal tissues of the peripheral and some of the tumours reference is made to the skin. HISTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF TUMOURS OF THE SOFT (MESENCHYMAL) TISSUES I. TUMOURS OF FIBROUS TISSUE C. RHABDOMYOMA A. FIBROMA D. RHABDOMYOSARCOMA 1. Fibroma durum IV. TUMOURS OF BLOOD AND 2. Fibroma molle LYMPH VESSELS 3. Myxoma (myxofibroma) A. CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA B. FIBROSARCOMA B. MALIGNANT HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA (ANGIO- 1. Fibrosarcoma SARCOMA) 2. " Canine haemangiopericytoma" C. GLOMUS TUMOUR C. OTHER SARCOMAS D. LYMPHANGIOMA D. EQUINE SARCOID E. LYMPHANGIOSARCOMA (MALIGNANT LYMPH- E. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS ANGIOMA) 1. Cutaneous fibrous polyp F. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS 2. Keloid and hyperplastic scar V. MESENCHYMAL TUMOURS OF 3. Calcinosis circumscripta PERIPHERAL NERVES II. TUMOURS OF FAT TISSUE VI. -

Aneurysmal Fibrous Histiocytoma: a Case Report and Review of the Literature Devin M

Aneurysmal Fibrous Histiocytoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature Devin M. Burr, DO,* Warren A. Peterson, DO,** Michael W. Peterson, DO*** *Dermatology Resident, 1st year, Aspen Dermatology Residency Program, Springville, UT **Program Director, Aspen Dermatology Residency Program, Springville, UT ***Dermatopathologist, Springville Dermatology, Springville, UT Disclosures: None Correspondence: Devin M. Burr, DO; [email protected] Abstract Dermatofibroma is one of the most common subcutaneous dermatologic tumors. In its classic variant, a dermatofibroma is easily recognized by dermatologists; however, studies have identified numerous variants of the dermatofibroma that do not present with a classic clinical picture. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, one of these variants, is not easily recognized given its bizarre growth and potentially malignant appearance. Microscopically, aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma can be difficult to identify, as the lesion will display some similarities to a classic dermatofibroma along with distinguishing characteristics, like large blood-filled cavernous spaces. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma is a benign lesion with a low risk for recurrence if adequately excised. In this paper, we present a case of aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma and review the literature on this rare dermatofibroma variant and what to consider on the differential diagnosis. Introduction right scapula. He reported that it had been present subcutis (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains Dermatofibroma, also known as fibrous for about one year and initially appeared as a 1 mm FXIIIa, CD10, and CD68 confirmed that the histiocytoma, is a common dermatologic to 2 mm purple papule. It slowly grew for the first lesion was a histiocytic tumor (Figure 4). CD34 subcutaneous tumor. It represents roughly 3% six months and then rapidly enlarged in size over highlighted the vascular component. -

Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumor of the Abdomen: a Case Report and Literature Review of Therapeutic Options

Vol.4, No.4, 207-211 (2012) Health http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/health.2012.44031 Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the abdomen: A case report and literature review of therapeutic options Hafida Benhammane1*, Leila Chbani2, Abdelmalek Ousadden3, Ouadii Mouquit3, Siham Tizniti4, Afaf Riffi Amarti2, Nouafal Mellas1, Omar El Mesbahi1 1Department of Medical Oncology, Hassan II University Hospital, Fez, Morocco; *Corresponding Author: [email protected] 2Department of Pathology, Hassan II University Hospital, Fez, Morocco 3Department of General Surgery, Hassan II University Hospital, Fez, Morocco 4Department of Radiology, Hassan II University Hospital, Fez, Morocco Received 22 December 2011; revised 18 January 2012; accepted 6 February 2012 ABSTRACT rent therapeutic options include multiagent chemothe- rapy and aggressive surgical debulking and radiotherapy Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is [4,5]. The addition of hyperthermic intra-peritoneal che- a rare and highly aggressive variety of sarcoma motherapy in the multimodal approach has been reported arising typically from abdominal or pelvic peri- in very few cases but no effect on survival has been clearly toneum. Diagnosis and treatment approaches of demonstrated [6]. this entity are complex and require a skilled, ex- The prognosis of this disease is poor with a Median perienced, multidisciplinary team. Authors re- survival of 17 months approximately [7]. port their experience with a case of an intra-ab- We report a case of an intra-abdominal DSRCT in a 37 dominal DSRCT arising in a 37-year-old young -year-old young man who was treated with combination man in order to discuss the clinico-pathological chemotherapy and surgery. -

FISH for Sarcoma Translocation Testing

Cleveland Clinic Laboratories FISH for Sarcoma Translocation Testing Background Information 2. the DDIT3 (CHOP) gene at 12q13 (myxoid/round cell liposarcoma). Soft tissue sarcomas are a histologically and genetically heterogeneous group of tumors, accounting for approximately 3. the FOX01A (FKHR) gene at 13q14 (alveolar rhabdomyo- 1% of all adult malignancies. Many sarcomas show charac- sarcoma). teristic combinations of morphologic and immunophenotypic 4. the SYT gene at 18q11.2 (synovial sarcoma). features, which, in concert with clinical information and tumor site, allow their appropriate classification. However, 5. the FUS gene at 16p11.2 (low-grade fibromyxoid their histologic features frequently overlap or may not be sarcoma, sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma, angiomatoid apparent due to poor differentiation or limited sampling in fibrous histiocytoma, myxoid liposarcoma). small biopsies. 6. the ALK gene at 2p23 (inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor). In recent years, molecular genetic findings have advanced the Interpretation basic scientific and clinical understanding of sarcomas and have become increasingly important in their precise diagnostic Detection via FISH of amplification of the MDM2 gene locus classification. Detection of chromosomal translocations in is also helpful in the differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors neoplastic cells is one of the molecular characteristics that of lipomatous derivation (see separate Technical Brief). can serve as a highly precise tool in diagnosis. These Optimal samples have a minimum of 40 tumor cells for analysis. chromosomal translocations result in specific gene fusions, and each gene fusion or its closely related variant is usually Positive test: present in most cases of a given sarcoma subtype. Such 10% or > cells showing a break-apart configuration of the highly specific genetic changes are known to exist in more two probes included in each of the individual assays. -

Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours Cyril Fisher

Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours Cyril Fisher To cite this version: Cyril Fisher. Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours. Histopathology, Wiley, 2010, 58 (7), pp.1001. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03707.x. hal-00613811 HAL Id: hal-00613811 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00613811 Submitted on 6 Aug 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Histopathology Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours ForJournal: Histopathology Peer Review Manuscript ID: HISTOP-08-10-0420 Wiley - Manuscript type: Review Date Submitted by the 01-Aug-2010 Author: Complete List of Authors: fisher, cyril; royal marsden hospital, histopathology Keywords: soft tissue tumours, immunohistochemistry, sarcoma, diagnosis Published on behalf of the British Division of the International Academy of Pathology Page 1 of 39 Histopathology Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours For PeerCyril FisherReview Royal Marsden Hospital, London UK Correspondence to: Prof Cyril Fisher MD DSc FRCPath Dept of Histopathology The Royal Marsden Hospital 203 Fulham Road London SW3 6JJ UK Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 207 808 2631 Fax +44 207 808 2578 Running Title : Soft Tissue Tumour Immunohistochemistry Key Words Immunohistochemistry, sarcoma, diagnosis, soft tissue tumour 1 Published on behalf of the British Division of the International Academy of Pathology Histopathology Page 2 of 39 Abstract Immunohistochemistry in soft tissue tumours, and especially sarcomas, is used to identify differentiation in the neoplastic cells. -

Treatment of Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma and Atypical Fibrous Xanthomas with Micrographic Surgery MARC D

Treatment of Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma and Atypical Fibrous Xanthomas with Micrographic Surgery MARC D. BROWN, M.D. NEIL A. SWANSON, M.D. HONORABLE MENTION Abstract. Fibrous tumors of the soft tissue are usually tumors is uncertain, but they probably arise from benign, but some fibrous neoplasms such as dermatofi- mesenchymal cells that show partial histiocytic and/ brosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma or fibroblastic differentiation.’,’ The more malig- (AFX), and malignant fibrohistiocytoma (MFH) can be very destructive locally with a high recurrence rate after nant of these tumors retain some degree of pleu- local excision. On occasion, they can metastasize. Pre- ropotentiality . vious reports have confirmed the high success rate of Fibrohistiocytic tumors can be classified accord- Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of DFSP, ing to their malignant potential. The most common but data have been lacking on the potential benefit of this fibrohistiocytic neoplasm is the benign dermatofi- surgical approach for MFH and AFX tumors. Over the past 6 years, we have treated 17 patients with MFH (20 broma, which has no invasive or malignant char- tumors) and 5 patients with AFX with Mohs micrographic acteristics and rarely requires surgical intervention. surgery. A retrospective analysis of the surgical results Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is con- is presented. To date (average 3-year follow-up), all pa- sidered a fibrohistiocytic sarcoma of intermediate tients contacted are tumor free with only one recurrence; malignancy. It bears a striking histologic similarity no patient has developed metastatic disease. Our results to date are very encouraging; they lend support to Mohs to the benign fibrous histiocytoma, but grows in a micrographic surgery as a desired surgical approach for more infiltrative fashion, has a more marked these diffiult-to-cure neoplasms. -

Malignant Dermatofibroma

Modern Pathology (2013) 26, 256–267 256 & 2013 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/13 $32.00 Malignant dermatofibroma: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of seven cases Thomas Mentzel1, Thomas Wiesner2, Lorenzo Cerroni2, Markus Hantschke1, Heinz Kutzner1, Arno Ru¨ tten1, Michael Ha¨berle3, Michele Bisceglia4, Frederic Chibon5 and Jean-Michel Coindre5 1Dermatopathology Bodensee Friedrichshafen, Friedrichshafen, Germany; 2Deparment of Dermatology, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria; 3Dermatological Practice, Ku¨nzelsau, Germany; 4IRCCS-CROB, Referral Cancer Center of Basilicata, Rionero in Vulture (PZ), Italy and 5Bergonie Institute, InsermU916 and University Victor Segalen Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France Dermatofibroma (cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma) represents a common benign mesenchymal tumor, and numerous morphological variants have been described. Some variants of dermatofibroma are characterized by an increased risk of local recurrences, and there are a few reported metastasizing cases. Unfortunately, an aggressive behavior cannot be predicted reliably by morphology at the moment, and we evaluated the value of array-comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) in this setting. Seven cases of clinically aggressive dermatofibromas were identified, and pathological and molecular features were evaluated. The neoplasms occurred in four female and in three male patients (mean age was 33 years, range 2–65 years), and arose on the shoulder, buttock, temple, lateral neck, thigh, ankle, and cheek. The size of the neoplasms ranged from 1 to 9 cm (mean: 3 cm). An infiltration of the subcutis was seen in five cases. Two neoplasms were completely excised, whereas an incomplete or marginal excision was reported in the remaining cases. Local recurrences were seen in six cases (time to the first recurrence ranged from 8 months to 9 years).