[2020] Wacor 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Register of Authorised Hospitals in Western Australia

Register of Authorised Hospitals in Western Australia Mental Health Act 2014 Section 542 Correct as of 4 August 2020 (OCP23859) www.chiefpsychiatrist.wa.gov.au Introduction Section 542 of the Mental Health Act 2014 provides for the Governor, by order published in the Western Australian Government Gazette to authorise a public hospital or part of a public hospital to be an ‘authorised hospital’ for the purposes of reception and admission of patients requiring involuntary treatment and care. Section 541 provides for a private hospital whose license is endorsed under section 26DA(2) of the Hospitals and Health Services Act 1927 to be an ‘authorised hospital’ on the recommendation by/of the Chief Psychiatrist, for the reception and admission of patients requiring involuntary treatment and care. Please Note: Grant of Leave under section 105(1)(a)(ii) of the Mental Health Act 2014 from an Authorised part of a Hospital to a Non-Authorised part of a Hospital Subdivision 2 of Division 6 of Part 7 of the Mental Health Act 2014 provides for the granting of leave for an involuntary detained patient from an authorised hospital. Section 105 (1)(a)(ii) provides specifically for leave to be granted to a General Hospital for a patient who requires medical or surgical treatment or treatment likely to benefit the inpatient’s physical health in some other way. When an authorised hospital is within a general hospital campus and an involuntary inpatient needs to be treated in the general part of the hospital it is as though it is leave being granted from the authorised facility to the general hospital, despite the fact that both hospitals (authorised and general) are within the same grounds. -

Ef.Aar15.161118.Aon.001.Jd.Pdf

According to our patients, the best Hospital contacts: thing about their health journey was: Armadale Health Service PO Box 460, ARMADALE WA 6112 “Found staff in “Every midwife Telephone: (08) 9391 2000 admissions very that I encountered www.ahs.health.wa.gov.au You’ve told us…. helpful to make sure was fantastic, what was being said friendly, kind and Bentley Health Service was understood.” knowledgeable.” PO Box 158, BENTLEY WA 6982 we’re listening Telephone: (08) 9416 3666 “The doctor in the “From a bad www.bhs.health.wa.gov.au resuscitation ward situation, my hospital gave the clearest and experience was Fiona Stanley Hospital most understandable excellent to help me Locked Bag 100, PALMYRA DC 6961 explanation I’ve ever care for myself in the Telephone: (08) 6152 2222 had.” future.” www.fsh.health.wa.gov.au Fremantle Hospital and Health Service PO Box 480, FREMANTLE WA 6959 Telephone: (08) 9431 3333 Where to from here www.fh.health.wa.gov.au Rockingham General Hospital Our individual hospitals are listening to their patients. PO Box 2033, Rockingham WA 6967 Your feedback is guiding the various teams to Telephone: (08) 9599 4000 reassess how they can better keep their patients and www.rkpg.health.wa.gov.au families informed throughout their hospital and health service journey. Royal Perth Hospital GPO Box X2213, PERTH WA 6847 Through ongoing patient experience surveys over the Telephone: (08) 9224 2244 next two years, we will continue to make the necessary www.rph.health.wa.gov.au changes to meet our patients’ expectations and build on what we already do well. -

Fiona Stanley Fremantle Hospital Group Joins Clintrial Refer in Western Australia

www.clintrial.org.au Contact Us Fiona Stanley Fremantle Hospital Group Joins ClinTrial Refer in Western Australia ClinTrial Refer is very pleased to welcome a new group of ve hospitals in Western Australia from the South Metropolitan Health Service to our research community. The South Metropolitan Health Service (SMHS) delivers hospital and community-based public health care services to a population of more than 657,800 within a catchment area stretching 3,300 square kilometers across the southern half of Perth and Western Australia. This catchment represents 25 per cent of the State’s population. The SMHS hospital network includes: Fiona Stanley Hospital Rockingham General Hospital Fremantle Hospital Murray District Hospital Peel Health Campus (public private partnership with Ramsey Health) “We are very excited to join the ClinTrial Refer App community to showcase our clinical trial capacity and capability, attract more participants and have an accessible information portal for our staff, referring clinicians and community members” said Melanie Wright, the Head of Research and Development for the South Metropolitan Health Service. “We have a thriving clinical trials community in medical oncology, haematology, gastroenterology, diabetes and more. Clinical trials offer our patients the latest and greatest treatments, close supervision and increased monitoring with the aim of improving clinical outcomes and quality of life.” Visit the SMHS - Fiona Stanley Fremantle Hospital Group on ClinTrial Refer or read more about SMHS Research here. Clinical Trial Spotlight: Focus on Teletrials What are Teletrials? There is an increasing focus on teletrials in the design and implementation of clinical trials, especially recently in light of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities and health care systems around the world. -

Research Proposal Has Been Approved

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2016 An investigation of nurse education service models in acute care metropolitan hospitals across Australia Carolyn Keane The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Nursing Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The am terial in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Keane, C. (2016). An investigation of nurse education service models in acute care metropolitan hospitals across Australia (Doctor of Nursing). University of Notre Dame Australia. http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/138 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Appendices Appendix 1. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards 276 Appendix 2: UNDA Ethics Approval Letter 277 Appendix 3: SMHS Nursing Research Review Committee Approval Letter Government of Western Australia Department of Health Fremantle Hospital and Health Service 3rd February 2014 Carolyn Keane A/Nursing Director, Corporate Services Fremantle Hospital Professional Doctorate in Nursing student, University of Notre Dame Australia. Professor Selma Alliex Dean of the school of nursing University of Notre Dame Australia. Dear Carolyn and Dr Alliex Project title: An Investigation of Nurse Education Services Models in Acute Care Metropolitan Hospitals across Australia. Thankyou for submitting the above project for review by the South Metro Health Service (SMHS) Nursing Research Review Committee. -

Health Department of Western Australia Healtha DISCUSSION PAPER

health2020A DISCUSSION PAPER THE METROPOLITAN HEALTH STRATEGIC PLANNING SERIES Health Department of Western Australia A CKNOWLEDGEMENT The many people and organisations who participated in the development of this discussion paper are acknowledged, particularly the Metropolitan Health Strategic Planning Committee who included: Dr Dianne McCavanagh Chairperson Representative, Health Department of Western Australia General Manager, Strategic Planning and Evaluation Dr Neale Fong Representative, Health Department of Western Australia Chief General Manager, Operations Dr Gareth Goodier Representative, Metropolitan Health Service Board Chief Executive Officer, PMH/KEMH Professor Louis Landau Representative, Metropolitan Health Service Board Executive Dean, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Western Australia Ms Helen Lynes Community Member Mrs Helen Morton Representative, Metropolitan Health Service Board General Manager, Armadale Health Service Dr Bryant Stokes Representative, Health Department of Western Australia Chief Medical Officer Particular thanks should go to those individuals who provided background papers on specific issues including Dr Bill Beresford, Mr Don Black, Dr Scott Blackwell, Mr Alan Buckley, Dr Penny Burns, Mr David Cronin, Mr Eric Dillon, Ms Judith Finn, Professor David Fletcher, Dr Peter Goldswain, Dr Gareth Goodier, Mr Ian Haupt, Professor Michael Hobbs, Professor D’Arcy Holman, Mr David Inglis, Mr David Jacobs, Ms Stephanie Kirkham, Mr Alex Kirkwood, Professor Louis Landau, Professor George Lipton, Ms -

JS Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Private Archives – Collection Listing MN 2617 Acc. 7114A FUNERAL EULOGIES, REV’D STUART GOOD The papers were donated to Battye Library by Revd Stuart Good on 6 November 2008 (Acc. 7114A). Holdings = 0.01m (1 CD) Access The J S Battye Library provides access to original material. In some situations, this may not be possible and alternative formats such as microfilm, microfiche, typescripts or photocopies are supplied for researchers’ use. Where alternative formats are available, these must be used. Copyright Restrictions The Commonwealth Copyright Act 1968 regulates copying of unpublished material. It is the user’s legal obligation to determine and satisfy copyright. SUMMARY OF CLASSES EULOGIES Excerpts from Funeral Addresses, 1968-2008, by the Revd Stuart Good, Anglican Priest The eulogies are arranged according to date deceased Table of Contents (listed by date deceased) No.1 Charles Arthur Pearson Gostelow, M.C., J.P. (Aged 77) Dec’d 1968 ... 8 No.2 Dr Guy Terence Wallace (aged 57) Dec’d 1970 .............................. 8 No.3 Leonard Lynton Atkins (aged 59) Dec’d 1971................................ 9 No.4 Mabel Alice Claughton (aged 76) Dec’d 1975 ................................ 9 No.5 Frances (Frankie) Mary Hall (aged 73) Dec’d 1978.......................... 9 No.6 Ruth Isabella Lilburne (aged 59) Dec’d 1978............................... 10 No.7 Vicky Anne Plester (aged 26) Dec’d 1979................................... 10 No.8 George Frederick O’Connor (aged 68) Dec’d 1979 ....................... 10 No.9 Eva Muriel Lucas, M.B.E. (aged 94) Dec’d 1979 ........................... 11 No.10 Robert Frederick Reeson (aged 70) Dec’d 1984 ........................ -

Department of Health Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee

Department of Health Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee Project Summaries for Approved Proposals April to June 2019 Quarter Project summaries for proposals approved by the Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee – April to June 2019 quarter. The material contained in this document is made available to assist researchers, institutions and the general public in searching for projects that have ethics approval from the Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee (DOH HREC). It contains lay description/summaries of projects approved in the April to June 2019 quarter. The mid and long term clinical outcomes in patients treated with Everolimus-Eluting Project Title Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold in public tertiary hospitals of Western Australia Principal Dr Imran Shiekh Investigator Institution Royal Perth Hospital Start Date 12 June 2019 Finish Date 12 June 2020 This is a retrospective cohort study of 376 patients who were treated with Absorb Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold in Western Australian public hospitals between 2012 to 2016. These patients were in different states of compromise, ranging from stable angina to acute coronary syndrome. Clinical registry data from the four public hospitals will be extracted for the cohort and linked with data on hospital admissions and death from the WA Data Linkage System. The treating clinicains see it as a duty of care to evaluate the outcomes in patients who were treated with Absorb Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold. The study will also help to provide better quality care in the follow-up of these patients. Evaluation of post-operative care following repair of gastroduodenal ulcer perforation, Project Title effect on patient outcomes and development of a new protocol Principal Dr Amanda Foster Investigator Institution Fiona Stanley Hospital Start Date 30 April 2019 Finish Date 31 December 2027 This is a retrospective study that aims to assess the post-operative management practices after surgical repair of peptic and duodenal ulcer perforation in an emergency setting. -

Patient Information Booklet

Fiona Stanley Fremantle Hospitals Group Patient information Fiona Stanley Hospital Contents Welcome to Fiona Stanley Hospital 2 Vending machines 6 Before you arrive – what to bring 3 Phones 6 Returning home 3 Mobile devices 6 The right care in the right place 3 Photography and recording 6 Smoking 6 My healthcare rights 4 Alcohol and drugs 6 Transport and parking 4 Pastoral Care Service 6 Public transport 4 Aboriginal Health Liaison Service 7 Taxi ranks 4 Interpreting services 7 Patient set down 4 Assistive devices 7 Paid parking 4 Preventing infections 7 Parking rates 4 Your identification 7 On arrival 5 Pressure injuries (bed sores) 7 Where do I need to go? 5 Medications 7 Private patients 5 Teaching 7 Admission 5 Involving your General Practitioner 7 Disability access 5 Feedback, compliments and complaints 8 On the ward 5 Patient and Family Liaison Service 8 Finding your way 5 Care Opinion 8 During your stay 5 Surveys 8 Health record 5 Donations 8 Patient enquiries 5 Carers WA 9 Visiting times 6 Map 10 Facilities 6 Patient entertainment 6 Meal times 6 Welcome to Fiona Stanley Hospital We would like you to be as comfortable as possible during your stay. This booklet is designed to provide you with information about what to expect during your hospital stay and what services and amenities are available for you and your visitors. Fiona Stanley Hospital (FSH) is the major tertiary hospital in the south metropolitan area, commissioned to meet the growing needs of communities south of Perth and across the State. We are committed to providing the very best patient care and provide high-quality health services including a full range of acute medical and surgical services, maternity, paediatric and neonate units, a State Rehabilitation Service, purpose-built mental health unit and the State burns service. -

Submission Is Attached at the End of This Submission

Dr Neville F Hills, FRANZCP, MRCPsych.,LLM, PhD. 23 January, 2020 Dear Commissioners, Re: Productivity Commission 2019, Mental Health, Draft Report, Canberra I am a retired psychiatrist with a special interest in aged care. Unfortunately I have only sighted this discussion paper today so my remarks are brief. May I say that as a Western Australian, I along with many others in this State, have a remote view of our Commonwealth Government, although I have worked in New South Wales and England in my career. As a largely State government employed psychiatrist, I have observed the extent to which our WA government has used the involvement of Commonwealth agencies and funding, to withdraw local services and resources built up over past decades. Increasing Commonwealth interventions in State managed health care is, in my experience, counter-productive. You must appreciate that Perth is as far from the Sydney-Canberra axis as Moscow is from London. Would people in London accept directions and distribution of their taxes from Moscow? This paper so far is a rehash of multiple State and Commonwealth motherhood statements and wish lists. Clinical staff have been well aware for decades what is needed to provide effective services, but instead we have seen restructuring repeatedly destroy good services, while chasing ephemeral and politically driven false concepts. In WA good State services have been dismantled and abandoned in the pursuit of false economies and rationalisations. The pursuit of privatisation at the expense of properly funded and managed State services has proved costly and ineffective. It is time to admit it has not worked in providing mental health care for seriously unwell people. -

Working with SMHS

Working with SMHS The South Metropolitan Health Service (SMHS) is a health service with a clear vision and plan; with staff that recognise no matter what role they have, they are contributing to enhancing our community’s health care. We value the contribution of every member of the team and encourage integration across professions, sites and services. southmetropolitan.health.wa.gov.au About South Metropolitan Health Service Our vision is to provide seamless access to innovative, safe, high quality health care through: One Focus One Team One Service Our patients and the Developing Alignment of resources, community – improving patient collaborative networks systems and processes across care and population health and partnerships. the health service to achieve outcomes. our goals. Integrated approach across professions, sites and services, sharing knowledge and expertise, recognising and building on strengths. Our Values: Care – by demonstrating commitment and consideration to others as we work. Respect – for each other, our clients and their families, carers and the community by preserving individual dignity and supporting the right of everyone to make choices. Excellence – by providing high quality, accessible, integrated and safe health care to the community. We believe in working in partnership with clients to improve their health. Integrity – by providing quality services and advice for the common good and having honest dealings and communication with other people. Teamwork – valuing the contribution of the team, working safely and cooperatively and communicating effectively with the team. Leadership – by communicating SMHS and WA Health’s Vision, taking responsibility for our actions and decisions and displaying trust in our colleagues. Working with SMHS 2 of 6 Our service The South Metropolitan Health Service (SMHS) delivers quality, safe and effective hospital and health services within a catchment area stretching more than 3300 square kilometres across the southern half of Perth. -

Who Can Make a Complaint Or Provide Feedback?

How to make a complaint in the WA Health System Carly Parry- Advocacy Manager In the WA Health System, anyone can make a complaint or provide feedback, including…….. • Consumers • Families • Carers • Visitors Making a complaint, which option is right for you? Direct to The Health Service If you wish to comment on, compliment or complain about, any service received in a hospital or health service, you might want to first raise your concerns with the attending staff, either verbally or in writing. If you want the service to provide you with a response, you can request this. You can ask the service to provide their response to you verbally and/or in writing. When providing feedback or making a complaint, let the service know if you are seeking a specific resolution/outcome. Resolution for you might be…. • An apology • A change to a service’s processes • A reimbursement or refund • A second medical opinion WA Hospitals and Public Health Services….. Each WA Public Health Service & Hospital has an internal department that manages complaints and feedback. These departments are often referred to as a Family, Patient or Consumer Liaison/ Experience Service. You can contact a hospital’s main switchboard and ask to be transferred to the Patient Liaison Office. You can make a complaint over the phone or in writing. WA Health (Public) Services, must follow the “Complaints Management Policy.” Under this policy, a health service should; • Aim to provide a response to you within 30 working days. If they need more time, they should let you know at 15 day intervals. -

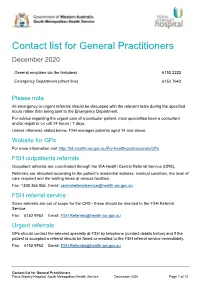

FSH Contact List For

Contact list for General Practitioners December 2020 General enquiries via the Helpdesk 6152 2222 Emergency Department (direct line) 6152 7642 Please note All emergency or urgent referrals should be discussed with the relevant team during the specified hours rather than being sent to the Emergency Department. For advice regarding the urgent care of a particular patient, most specialties have a consultant and/or registrar on call 24 hours / 7 days. Unless otherwise stated below, FSH manages patients aged 14 and above. Website for GPs For more information visit http://fsh.health.wa.gov.au/For-health-professionals/GPs FSH outpatients referrals Outpatient referrals are coordinated through the WA Health Central Referral Service (CRS). Referrals are allocated according to the patient’s residential address, medical condition, the level of care required and the waiting times at various facilities. Fax: 1300 365 056 Email: [email protected] FSH referral service Some referrals are out of scope for the CRS - these should be directed to the FSH Referral Service. Fax: 6152 9762 Email: [email protected] Urgent referrals GPs should contact the relevant specialty at FSH by telephone (contact details below) and if the patient is accepted a referral should be faxed or emailed to the FSH referral service immediately. Fax: 6152 9762 Email: [email protected] Contact list for General Practitioners Fiona Stanley Hospital, South Metropolitan Health Service December 2020 Page 1 of 12 Specialty Routine enquiries