English Baroque Masters Tenebrae Nigel Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECONOMIC EAR Symphonic Tigers and Chamber Kittens

ANALYSIS ECONOMIC EAR Symphonic tigers and chamber kittens In the fifth of our series of articles on the business of classical music, Antony Feeny reflects on the extent to which the UK music industry may be dominated by a few large organisations ans Sachs was a remarkably like to ensure free competition and level example, and the top four supermarkets and productive artist if the com- playing fields, those pesky markets persist in top four banks have over 70% of the British mon sources are to be believed. becoming more concentrated and awkward grocery store and retail banking markets, HIn addition to keeping the inhabitants of ruts will keep appearing in those playing while the top six energy suppliers account Nürnberg well-heeled, he apparently cob- fields. And so it seems with classical music. for 90% of the UK market. But these are bled together 4,000 Meisterlieder between Was Le Quattro Staggioni – well-known (relatively) free markets where commercial 1514 and his death in 1576. That’s about to every denizen of coffee shops and call cen- companies compete, so what’s the situa- one every five-and-a-half days every year tres – really so much ‘better’ than works by tion for classical music – a market which is for 62 years including Sundays, in addition the Allegris, the Caccinis, Cavalli, Fresco- subsidised and where its leading organisa- to his other 2,000 poetic works – not to baldi, the Gabrielis, Landi, Rossi, Schütz, or tions are best semi-commercial, or at least mention shoes for the 80,000 feet of those the hundreds of other 17th-century compos- non-profit-making? Nurembergers, or at least the wealthy ones. -

English National Ballet Solstice Southbank Centre's Royal Festival Hall, London 16 - 26 June 2021

English National Ballet Solstice Southbank Centre's Royal Festival Hall, London 16 - 26 June 2021 www.ballet.org.uk/solstice This summer (16 - 26 June) English National Ballet presents Solstice, a programme of diverse repertoire highlights, at the Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall. Solstice features highlights from classics like Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and Le Corsaire as well as a passionate duet from Broken Wings, Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s ballet inspired by the life of Frida Kahlo, Stina Quagebeur’s Hollow and joyous steps from Coppélia. There are moments of reflection and tenderness in extracts from Akram Khan’s Dust and Ben Stevenson’s Three Preludes, set to Rachmaninov’s music and the programme concludes with William Forsythe’s Playlist (Track 1, 2), a high-energy work set to neo-soul and house music. Tamara Rojo CBE, English National Ballet’s Artistic Director said: “I'm so pleased we will be performing at the Royal Festival Hall this summer. After so long without performing in theatres it's wonderful to have the opportunity to have so many of the Company back on stage showcasing highlights from English National Ballet's much loved and diverse repertoire.” Accompanied by live music performed by musicians of English National Ballet Philharmonic, Solstice follows English National Ballet’s return to the stage at Sadler’s Wells earlier this month. All rehearsals and performances are in strict compliance with the UK Government’s COVID- 19 guidance Photos are available to download here using the login details below: Login: press Password: ENBPress2021 Watch the trailer for Solstice here All rehearsals and performances are in strict compliance with the UK Government’s COVID- 19 guidance. -

Resonate: Centuries of Meditations by Dobrinka Resonate: Centuries of Meditations by Dobrinka

https://prsfoundation.com/2019/04/23/new‐resonate‐pieces‐announced/ Home > New Resonate Pieces Announced UK orchestras to champion 11 of the best pieces of British orchestral music from the past 25 years through PRS Foundation’s Resonate programme. Orchestras supported include City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Ulster Orchestra, Dunedin Consort & Scottish Ensemble, and the London Symphony Orchestra Pieces selected include Oliver Knussen’s The Way to Castle Yonder – Pot‐pourri after the Opera Higglety, Pigglety Pop, Thomas Adès’ Violin Concerto ‘Concentric Paths’ and Four Tributes to 4 am by Anna Meredith PRS Foundation, the UK’s leading funder of new music and talent development across all genres announces the 10 UK orchestras being supported through the third round of Resonate, a partnership with the Association of British Orchestras and BBC Radio 3, which champions outstanding pieces of British orchestral music from the past 25 years and aims to inspire more performances, recordings and broadcasts of these works. The orchestras and Resonate pieces to be programmed into their upcoming 2019/20 programmes are: Aurora Orchestra: Thomas Adès, Violin Concerto ‘Concentric Paths’ London Philharmonic Orchestra: Ryan Wigglesworth, Augenlieder City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra: Oliver Knussen, The Way to Castle Yonder – Pot‐pourri after the Opera Higglety, Pigglety Pop London Symphony Orchestra: Colin Matthews, Violin Concerto Dunedin Consort & Scottish Ensemble: James MacMillan, Seven Last Words from the Cross Southbank Sinfonia: Anna Meredith, Four Tributes to 4 am City of London Sinfonia (CLS): Dobrinka Tabakova, Centuries of Meditations Ulster Orchestra: Howard Skempton, Lento Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (Ensemble 10/10): Steve Martland, Tiger Dancing and Tansy Davies, Iris Birmingham Contemporary Music Group: Shiori Usui, Deep Resonate is a fund and resource which aims to inspire more performances, recordings and broadcasts of outstanding contemporary repertoire, as chosen by UK orchestras. -

Nicholas Collon Conductor

17 March 2021 7.30pm Guildhall Symphony Orchestra Nicholas Collon Conductor Guildhall School of Music & Drama Founded in 1880 by the Johannes Brahms City of London Corporation Symphony No 3 Chairman of the Board of Governors Vivienne Littlechild MBE JP in F major, Op 90 Principal Lynne Williams AM Edward Elgar Vice-Principal & Director of Music Jonathan Vaughan FGS DipRCM (Perf) DipRCM (Teach) Symphony No 1 in A-flat major, Op 55 Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk Guildhall Symphony Orchestra Nicholas Collon conductor Wednesday 17 March 2021 7.30pm As Guildhall School has very recently Guildhall School returned to blended-learning allowing is part of Culture Mile: rehearsals to take place in-person, this culturemile.london programme was rehearsed and performed on a reduced schedule over three days. It was performed live across three venues on Guildhall School is provided Wednesday 10 March 2021 and was recorded by the City of London as part of its contribution to the cultural and produced live by Guildhall School’s life of London and the nation. Recording & Audio Visual department. Johannes Brahms (1833–97) Symphony No 3 in F major, Op 90 (1883) 1. Allegro con brio The three-part Poco allegretto is a graceful intermezzo, whose 2. Andante opening theme flows like a river (could this be Brahms’s answer 3. Poco allegretto to Czech composer Smetana’s tribute to the River Vltava in his 4. Allegro cycle of orchestral tone-poems, Má vlast?). The central section brings another pastoral impression, with woodwind answered by Brahms was aged 50 when he wrote the third of his four strings. -

Press Release Shortlists Announced

Press Release For release: strictly embargoed until 7pm, Thursday 8 April 2010 Shortlists announced for RPS Music Awards Shortlists have been announced for this year’s RPS Music Awards, the UK’s most prestigious accolade for live classical music. Presented in association with BBC Radio 3, this year’s shortlists, for outstanding achievement in 2009, celebrate an astonishingly diverse range of music and music makers from across the UK. They reveal an exciting new generation of artists and ensembles who are firmly establishing themselves alongside distinguished performers; all demonstrate vision and boldness. The shortlists celebrate opera in CornwallCornwall, pianos in HuddersfieldHuddersfield, nationwide singing and outstanding celebrations of the year’s big anniversaries: Purcell, Handel, Haydn and Martinu. English National Opera, the London Sinfonietta, Southbank CentreCentre, conductor Oliver Knussen and pianist Stephen Hough are amongst the big names to make the cut. Young artists include violinist Alina IbragimovaIbragimova,Ibragimova 22 year old flautist Adam WalkerWalker, singers Iestyn Davies and Lucy CroweCrowe, conductor Kirill Karabits and ensembles the London Contemporary Orchestra and Aurora Orchestra in only their second and fourth seasons respectively. Huddersfield Contemporary MusicMusic FFestivalestival tops the list with three nominations, with the Philharmonia Orchestra, Wigmore Hall, BBC Symphony OrchestraOrchestra, and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra with its conductor Andris Nelsons each shortlisted twice. Graham SheffieldSheffield, Chairman of the Royal Philharmonic Society comments: “These shortlists have been debated and chosen by independent juries of incisive minds and strong opinions, and reflect the nominations of musicians and music lovers nationwide. What they reveal is the breadth of talent and invention in classical music in the UK on an unprecedented scale, and it is particularly refreshing to see so many young artists making a splash in 2009. -

Classical Season 2020 / 21

CLASSICAL SEASON 2020 / 21 Welcome Our Classical Season 2020/21 offers an exciting vision for classical music, now and for years to come. We welcome three award-winning musicians as our new Associate Artists. Our four resident orchestras, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Philharmonia Orchestra, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and the London Sinfonietta, present series jam-packed with outstanding music – including farewell seasons from the LPO’s Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor Vladimir Jurowski, and Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor of the Philharmonia, Esa-Pekka Salonen. As part of their final seasons, both conductors will exploit the dramatic possibilities of the Royal Festival Hall, with a complete Wagner Ring Cycle from Jurowski and a concert staging of Strauss’ Elektra from Salonen. The great pianist Daniel Barenboim returns to our much-loved hall and we are also proud to present Europe’s oldest civic orchestra, the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig. I look forward to seeing you here, at the beating heart of classical music in London. Elaine Bedell Chief Executive, Southbank Centre Southbank Centre has always been a natural home for musicians who are pushing music forward in new directions. Our three new Associate Artists – pianist Víkingur Ólafsson, violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja and composer Bryce Dessner – are leading the way in changing the landscape of classical music. Some of this season’s many highlights include a weekend dedicated to the haunting music of Canadian composer Claude Vivier, our global new music festival SoundState, and a setting of the Extinction Rebellion manifesto by British composer Laura Bowler. This is music that really has something to say, and we are strongly focused on widening the audience it speaks to. -

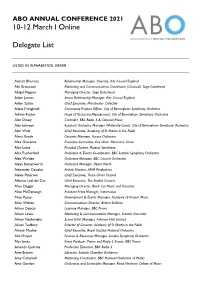

10-12 March I Online Delegate List

ABO ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2021 10-12 March I Online Delegate List LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER Aakash Bharania Relationship Manager, Diversity, Arts Council England Abi Groocock Marketing and Communications Coordinator (Classical), Sage Gateshead Abigail Pogson Managing Director, Sage Gateshead Adam Jeanes Senior Relationship Manager, Arts Council England Adam Szabo Chief Executive, Manchester Collective Adele Franghiadi Community Projects Officer, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Adrian Rutter Head of Orchestra Management, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Alan Davey Controller, BBC Radio 3 & Classical Music Alan Johnson Assistant Orchestra Manager (Maternity Cover), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Alan Watt Chief Executive, Academy of St Martin in the Fields Alana Grady Concerts Manager, Aurora Orchestra Alex Gascoine Executive Committee Vice Chair, Musicians' Union Alex Laing Principal Clarinet, Phoenix Symphony Alex Rutherford Orchestra & Events Co-ordinator, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Alex Walden Orchestra Manager, BBC Concert Orchestra Alexa Butterworth Orchestra Manager, Opera North Alexander Douglas Artistic Director, ADM Productions Alexis Paterson Chief Executive, Three Choirs Festival Alfonso Leal del Ojo Chief Executive, The English Concert Alice Dagger Managing Director, Black Cat Music and Acoustics Alice McDonough Assistant Artist Manager, Intermusica Alice Pusey Development & Events Manager, Academy of Ancient Music Alice Walton Communications Director, Britten Sinfonia Alison Dancer Learning Manager, BBC -

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Saturday, May 11, 2019 at 8:00pm Sunday, May 12, 2019 at 3:00pm, George Weston Recital Hall Nicholas Collon, conductor Shai Wosner, piano Edward Elgar Serenade in E Minor for String Orchestra, Op. 20 I. Allegro piacevole II. Larghetto III. Allegretto Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 21 in C Major, K. 467 I. [Allegro maestoso] II. Andante III. Allegro vivace assai Intermission Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 I. Allegro con brio II. Andante con moto III. Allegro IV. Allegro The Three at the Weston Series performances are generously supported by Margaret and Jim Fleck. As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. MAY 11 & 12, 2019 9 ABOUT THE WORKS Edward Elgar Serenade in E Minor for String Orchestra, Op. 20 Born: Broadheath, United Kingdom, June 2, 1857 12 Died: Worcester, United Kingdom, February 23, 1934 min Composed: 1892 Numerous front-rank British composers, He revised and re-titled the three pieces in the including Vaughan Williams, Britten, and spring of 1892, in time to offer what he then called Holst, have found writing for the rich, Serenade as a third anniversary present to his expressive, and flexible medium of the string wife, Alice. The first performance of that version— orchestra a highly congenial practice. Elgar’s two compact, animated sections framing the contributions were small in number but heart of the work, a haunting Larghetto—was substantial in every other sense. -

London Serenade Aurora Orchestra with Allan Clayton & Pip Eastop

VIOLIN I VIOLA Alexandra Wood* Hélène Clément* Marcus Barcham-Stevens* Ruth Gibson* Mon 21 Jun | 7.30pm Tristan Gurney* Nicholas Bootiman Live from Kings Place Hall One Marciana Buta* CELLO Ian Watson* London Serenade Sébastien van Kuijk* Aurora Orchestra with VIOLIN II Reinoud Ford* Jamie Campbell* DOUBLE BASS Allan Clayton & Pip Eastop Maria Spengler* Ben Griffiths* Cassandra Hamilton *Whitley strings Programme Tamara Elias Kate Whitley Allan Clayton MBE tenor Autumn Songs Pip Eastop horn Nicholas Collon conductor Edward Elgar Introduction & Allegro for strings, Op. 47 I. Introduction II. Allegro Benjamin Britten Serenade for Tenor, Horn & Strings, Op. 31 I. Prologue V. Dirge (Anon., 15th century) II. Pastoral (Cotton) VI. Hymn (Ben Jonson) III. Nocturne (Tennyson) VII. Sonnet (Keats) IV. Elegy (Blake) VIII. Epilogue William Walton Sonata for String Orchestra I. Allegro III. Lento II. Presto IV. Allegro molto This performance will last approx. 90 mins with no interval. A very warm welcome to this evening’s concert. Enigma Variations). Jaeger suggested Elgar produce Although seating capacities remain restricted at ‘a brilliant, quick String Scherzo… a real bring-down- present, it’s a terrific pleasure to be sharing music the-house torrent of a thing’ for the newly-formed again with a live audience, as well as with those London Symphony Orchestra and the composer duly watching online and listening on BBC Radio 3. agreed, completing the work around six months later. After many months of being restricted to smaller The resulting piece remains one of the high-points chamber repertoire on the stage here at Kings of the string repertoire, yet its initial reception was Place, it’s particularly exciting to be welcoming unexpectedly cool: ‘Nothing better for strings has back Nicholas Collon and a full string section for our ever been done,’ Elgar lamented, ’and they don’t like it.’ largest-scale orchestral performance here in Hall One since January 2020. -

Beethoven-7-Programme-FINAL.Pdf

Mon 7 September 2020 West Handyside Canopy, Kings Cross 6pm & 8.15pm Welcome A very warm welcome to this evening’s very special concerts: Aurora’s first since the start of March, and the first public, ticketed performances of a full-scale orchestral symphony anywhere in the UK since the imposition of lockdown. It's difficult to express what a moving and precious experience it has been to come together again as a group over the past few days and to make music together after such a long period of enforced separation. Whilst we remain a long way from anything resembling a ‘normal’ calendar of performing activity, this week’s series of concerts – here at Kings Cross, in Saffron Walden on Wednesday and at the BBC Proms on Thursday night – mark a hugely important milestone. We're intensely grateful to the many partners who have made the project possible, including Argent, our hosts here at Kings Cross; Kings Place; Saffron Hall; and the team at the BBC Proms who have been so supportive of these outdoor performances in advance of our televised performance of this symphony at the Royal Albert Hall on Thursday. We are particularly grateful to Kings Place and the Parabola Foundation, whose financial support has helped us to mount these special outdoor performances as part of a newly-adapted version of our Kings Place season, and to the many other organisational funders listed in the acknowledgments below whose generosity has helped to sustain Aurora during the past intensely challenging months. Lastly we are grateful to Aurora’s extended family of patrons and friends for their ongoing support of our work – your assistance has been more vital now than ever before, and we are so pleased that many of you are able to be with us in person this evening for the first time in many months. -

Press Release Southbank Centre Announces 2019/20 Classical Season

Press Release Date: Monday 18 February 2019 Contact: Sophie Cohen, [email protected] / 020 7921 0973 OR Naomi French, [email protected] / 020 7921 0678 2019/20 Classical Season Event Listings HERE Images available to download HERE Southbank Centre announces 2019/20 Classical Season Southbank Centre is proud to announce its 2019/20 season of concerts across its three world renowned venues. With over 230 concerts, the season reflects Southbank Centre’s commitment to classical music and to celebrating its position as one of the UK’s most important venues for the arts. Photo credits: Anoushka Shankar, credit Anushka Menon; Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla photo Benjamin Eloveaga; Bridget Riley Movement in Squares, 1961 Synthetic emulsion on board 123.2 x 121.2 cm © Bridget Riley 2018. All rights reserved. (Part of Hayward Gallery’s Bridget Riley exh bition 23 October 2019 - 26 January 2020); Sean Shibe photo Kaupo Kikkas. Highlights include: ● Major series in 2020 celebrating 250 years since the birth of Beethoven ● The return of Steve Reich’s Drumming to the Hayward Gallery, the site of its European premiere in 1972, headlines a season of music inspired by visual art and the Hayward Gallery’s major Bridget Riley retrospective ● Concerts and exhibition celebrating Ravi Shankar centenary ● Anoushka Shankar announced as Southbank Centre Associate Artist ● Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla conducts Varèse’s complete works ● International Orchestras include: San Francisco Symphony Orchestra double-bill; Bergen Philharmonic and Choir and an all-star cast in Britten’s Peter Grimes; Mitsuko Uchida and the Mahler Chamber Orchestra ● Over 30 new commissions and premieres and the launch of the first BBC Radio 3 Unclassified Live as part of a new ‘Contemporary Edit’ ● Southbank Centre to offer a free classical night out with the best in the business to audiences new to classical music. -

London Sinfonietta 2020/21 Season: First Events Announced

PRESS RELEASE LONDON SINFONIETTA 2020/21 SEASON: FIRST EVENTS ANNOUNCED 26 September 2020 – 7 July 2021 “The world’s top new music ensemble” The Times The London Sinfonietta announces its first events for the 2020 / 21 season featuring a host of exciting and significant premieres that seek to reflect and engage with the world we live in. Resident Orchestra at Southbank Centre and Artistic Associates at Kings Place, the London Sinfonietta continues to create fertile collaborations between other genres and disciplines, and uses its artistic programme as a catalyst to engage wider communities as well as develop audiences both live and online. SEASON SUMMARY - Nine premieres as part of Southbank Centre season including a new commission by Laura Bowler, inspired by Extinction Rebellion manifesto, plus new works by James Dillon and George Lewis - Wide ranging opportunities for the public to take part and create alongside the London Sinfonietta throughout its season - New Digital Channel expands to include new binaural digital commissions with an inaugural work by Shiva Feshareki - Performing in association with Music Theatre Wales presenting tour of major new work by Tom Coult and Alice Birch - New composers and performers given opportunities to develop their professional work through Writing The Future, Blue Touch Paper, London Sinfonietta Academy programmes A NOTE FROM ANDREW BURKE, CHIEF EXECUTIVE & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: We believe that new music matters to society, and the work of the London Sinfonietta can act as a catalyst for positive development in individuals and communities. Work we produce with composers and artists can both reflect what is happening and, in some way, influence change.