Native Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulse March 2020

South West Hospital and Health Service Getting ready for Harmony Week 2020 from Cunnamulla were (clockwise from left) Tina Jackson, Deirdre Williams, Kylie McKellar, Jonathan Mullins, Rachel Hammond Please note: This photo was taken before implementation of social distancing measures. PULSE MARCH 2020 EDITION From the Board Chair Jim McGowan AM 5 From the Chief Executive, Linda Patat 6 OUR COMMUNITIES All in this together - COVID-19 7 Roma CAN supports the local community in the fight against COVID-19 10 Flood waters won’t stop us 11 Everybody belongs, Harmony Week celebrated across the South West 12 Close the Gap, our health, our voice, our choice 13 HOPE supports Adrian Vowles Cup 14 Voices of the lived experience part of mental health forum 15 Taking a stand against domestic violence 16 Elder Annie Collins celebrates a special milestone 17 Shaving success in Mitchell 17 Teaching our kids about good hygiene 18 Students learn about healthy lunch boxes at Injune State School 18 OUR TEAMS Stay Connected across the South West 19 Let’s get physical, be active, be healthy 20 Quilpie staff loving the South West 21 Don’t forget to get the ‘flu’ shot 22 Sustainable development goals 24 Protecting and promoting Human Rights 25 Preceptor program triumphs in the South West 26 Practical Obstetric Multi Professional Training (PROMPT) workshop goes virtual 27 OUR SERVICES Paving the way for the next generation of rural health professionals 28 A focus on our ‘Frail Older Persons’ 29 South West Cardiac Services going from strength to strength 30 WQ Pathways Live! 30 SOUTH WEST SPIRIT AWARD 31 ROMA HOSPITAL BUILD UPDATE 32 We would like to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. -

Some Emerging Issues in Relation to Claims to Land Under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (Nsw)

2011 Emerging Issues: Claims to Land under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) 811 SOME EMERGING ISSUES IN RELATION TO CLAIMS TO LAND UNDER THE ABORIGINAL LAND RIGHTS ACT 1983 (NSW) JASON BEHRENDT ∗ I INTRODUCTION In 1983, the New South Wales Parliament passed the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) (‘ ALRA ’). The necessity to provide Aboriginal people with economic independence as well as providing compensation for past injustice was at the forefront of the policy underlying the enactment of the ALRA . In his second reading speech, the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Frank Walker noted that the Keane Report 1 prepared by the Parliamentary Select Committee that preceded the ALRA had noted that Aboriginal people experienced ‘severe economic deprivations’ and that the Committee believed that ‘land rights could also, in our times, lay the basis for improving Aboriginal self-sufficiency and economic wellbeing’. 2 He stated that ‘[i]n this sense land rights has a dual purpose – cultural and economic. Some lands, with traditional significance to Aborigines, will retain a cultural and a spiritual significance. Other lands will be developed as commercial ventures designed to improve living standards’. 3 The legislative policy expressed in the ALRA to return land to the Aboriginal people as ‘a form of economic compensation’ was noted by Sheller J in Minister Administering the Crown Lands Act v New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council .4 For the last 25 years, the ALRA has operated with mixed success. Although Frank Walker anticipated a quick process for the resolution of claims, the process of determining claims and transferring the land has taken much longer. -

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar This Book Is Available As a Free Fully-Searchable Ebook from Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language (revised edition 2018) by Mark Clendon Linguistics Department, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide Level 14, 115 Grenfell Street South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 Mark Clendon, 2018 for this revised edition This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] -

Hope for the Future for I Know the Plans I Have for You,” Declares the Lord, “Plans to Prosper You and Not to Harm You, Plans to Give You Hope and a Future

ISSUE 3 {2017} BRINGING THE LIGHT OF CHRIST INTO COMMUNITIES Hope for the future For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future Jeremiah 29:11 Lifting their voices What it’s like in their world Our first Children and Youth A new product enables participants Advocate will be responsible to experience the physical and for giving children and young mental challenges faced by people people a greater voice. living with dementia. networking ׀ 1 When Jesus spoke again to the people, he said, I am the light of the world. Contents Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life. John 8:12 (NIV) 18 9 20 30 8 15 24 39 From the Editor 4 Zillmere celebrates 135 years 16 Research paves way for better care 30 networking Churches of Christ in Queensland Chief Executive Officer update 5 Kenmore Campus - ready for the future 17 Annual Centrifuge conference round up 31 41 Brookfield Road Kenmore Qld 4069 PO Box 508 Kenmore Qld 4069 Spiritual Mentoring: Companioning Souls 7 Hope for future managers 19 After the beginnings 32 07 3327 1600 [email protected] Church of the Outback 8 Celebrating the first Australians 20 Gidgee’s enterprising ways 33 networking contains a variety of news and stories from Donations continue life of mission 9 Young, vulnerable and marginalised 22 People and Events 34 across Churches of Christ in Queensland. Articles and photos can be submitted to [email protected]. -

Gunggari People #3 and Local Governement ILUA External

QI2014/082 Gunggari People #3 and Maranoa Regional Council ILUA Schedule 2 Written Descriptions of Agreement Area Page 1 of 4 Page 1 of 4 Gunggari People #3 and Local Governement ILUA The agreement area covers all the lands and waters within the external boundary of QUD548/2012 Gunggari People #3 (QC2012/013) as accepted for registration 11/01/2013. External Boundary Description Described as: Commencing at a point at Longitude 148.326183° East, Latitude 26.304873° South; being the intersection of the external boundaries of Native Title Determination Application QUD216/08 Bidjara People (QC2008/005) and Native Title Determination Application QUD366/08 Mandandanji People (QC2008/010), and extending generally southerly along the western boundary of Native Title Determination Application QUD366/08 Mandandanji People (QC2008/010) to its intersection with the the western bank of Mananoa River, at Latitude 27.555703° South. Further described as: Commencing at a point at Longitude 148.326183° East, Latitude 26.304873° South and extending generally southerly to a point on the western bank of Mananoa River at Latitude 27.555703° South, passing through the following coordinate points: Longitude ° East Latitude ° South 148.326165 26.308980 148.329173 26.328224 148.330866 26.345408 148.332556 26.363410 148.332484 26.380573 148.339003 26.405988 148.340676 26.428486 148.348077 26.455546 148.355063 26.476879 148.360271 26.501052 148.368160 26.519125 148.376069 26.532294 148.376921 26.540886 148.376876 26.552738 148.376822 26.566633 148.376706 26.596875 -

Southern and Western Queensland Region

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): SAD6011/1998 NNTT Number: SCD2016/001 Determination Name: Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia Date(s) of Effect: 6/04/2018 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in parts of the determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 23/06/2016 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Note 1: On 6 April 2018 Justice White of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) ordered that: 1. The Determination of native title made on 23 June 2017 [sic] in Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia (No 2) [2016] FCA 724 be amended in accordance with the Amended Determination attached as Annexure A to this order, noting that because of the size of the Determination Annexure A comprises only: a. pages i to xv inclusive of the Amended Determination; b. the first page of any Schedule which is amended; and c. the particular pages within each Schedule which are amended. 2. Order 2 made on 23 June 2016 be vacated. 3. In its place there be an order that the Determination as amended take effect from the date of this order. Note 2: In the Determination orders of 23 June 2016, Order 22 deals with the nomination of a prescribed body corporate. On 19 December 2016 the applicant nominated to the Court in accordance with sections 56 and 57 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that: (a) native title is not to be held in trust; National Native Title Tribunal Page 1 of 20 Extract from the National Native Title Register SCD2016/001 and, accordingly, pursuant to Order 22(b) of 23 June 2016: (b) the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation is nominated as the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of section 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). -

NARRATIVE REPORT 31 July – 3 August, 2015

NARRATIVE REPORT 31 July – 3 August, 2015 Message from our Director The Yothu Yindi Foundation is proud to have produced, directed & hosted yet another compelling Garma at the Gulkula ceremonial grounds in northeast Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia. As an indigenous woman, it is difficult to put into words how much of an an honour it is to direct this wonderful experience, as we seek to extract the raw beauty of Australia’s Indigenous people & our incredible cultural heritage. Moreover, I take great pride in staging an event that also provides a healthy economic return to the Arnhem region by tapping the rich veins of the NT's tourism market and beyond. It is a humbling experience to showcase northeast Arnhem Land to the nation and the world as we strive to shape the national & political conversation on Indigenous affairs from a grass roots perspective. The Yothu Yindi Foundation would like to thank everyone who has contributed to the success of Garma. I would personally like to thank our guests for making the pilgrimage north to join us; thank you all for your continued contribution to the reconciliation process between black & white Australia & thank you for taking part in some of the challenging conversations needed to further advance the cause. As in previous years, the 17th annual Garma delivered a wide-ranging program that mixed the exciting with the informative, the eye-catching with the educational, as we sought to provide an action packed program appealing to everyone over four days & nights. Our aim is to develop our activities & objectives through the use of artistic and cultural practices which ensure Yolngu ownership, drive & direction are the foundational anchors to success. -

Evolution of Rights to Self-Determinism of Aboriginal People: a Comparative Analysis of Land Rights Reforms in Australia Alex Sadler, Divya Gupta Bowdoin College

Indigenous Policy Journal Vol. XXIX, No. 3 (Winter 2019) Evolution of Rights to Self-Determinism of Aboriginal People: A Comparative Analysis of Land Rights Reforms in Australia Alex Sadler, Divya Gupta Bowdoin College Abstract Despite Australia’s ratification of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2009, Aboriginal peoples continue to face obstacles in exercising their inherent rights to self-determination and to free, prior and informed consent regarding the development of their traditional land. Recent decades have seen advancements in legislation and government-backed programming to support the recognition of Aboriginal peoples’ land rights; however, the current framework often fails to achieve meaningful outcomes for impacted communities. This paper provides an overview of Australia’s current legislative and programming efforts to secure Aboriginal peoples’ land rights, evaluating the benefits and downsides to each initiative from a rights- based perspective, with the aim of promoting productive discourse on pathways to protecting and implementing the rights enshrined in the UNDRIP. Introduction In 2009, Australia ratified the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), after being one of only four countries to vote against its adoption in 2007. In reversing its decision, Australia symbolically demonstrated its commitment to the global shift towards the recognition of indigenous peoples’ inherent rights, which as the Declaration outlines derive from “their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies.” (United Nations, 2008) Although the UNDRIP covers a range of rights, from culture and identity to employment and education, a core focus of the agreement is the right of indigenous peoples to determine the development of their people and traditional land according to their own needs and interests. -

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Marie Geissler All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5546-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5546-4 Front Cover: John Mawurndjul (Kuninjku people) Born 1952, Kubukkan near Marrkolidjban, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory Namanjwarre, saltwater crocodile 1988 Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta) 206.0 x 85.0 cm (irreg) Collection Art Gallery of South Australia Maude Vizard-Wholohan Art Prize Purchase Award 1988 Accession number 8812P94 © John Mawurndjul/Copyright Agency 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Prologue ..................................................................................................... ix Theorizing contemporary Indigenous art - post 1990 Overview ................................................................................................ -

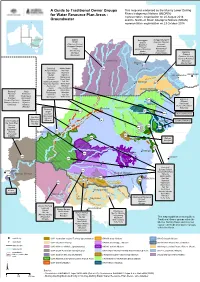

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

Indigenous Geographies of Home at Orient Point, NSW

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Social Sciences - Honours Theses University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2017 Indigenous Geographies of Home at Orient Point, NSW Hilton Penfold University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/thss University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Penfold, Hilton, Indigenous Geographies of Home at Orient Point, NSW, GEOG401: Human Geography (Honours), SGSC, University of Wollongong, 2017. https://ro.uow.edu.au/thss/14 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong.