Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the USS Florida Letter

Guide to the William F. Keeler Letter, 1863 February MS0457 The Mariners' Museum Library At Christopher Newport University Contact Information: The Mariners' Museum Library 100 Museum Drive Newport News, VA 23606 Phone: (757) 591-7782 Fax: (757) 591-7310 Email: [email protected] URL: www.MarinersMuseum.org/library Processed by Bill Edwards-Bodmer, March 2010 DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY Repository: The Mariners' Museum Library Title: William F. Keeler Letter Inclusive Dates: 1863 February Catalog number: MS0457 Physical Characteristics: 1 letter Language: English Creator: Keeler, William Frederick, 1821-1886 SCOPE AND CONTENT This collection consists of a single letter written by William F. Keeler on February 13, 1863 to David Ellis informing the latter that he had been appointed the Paymaster’s Steward on USS Florida. This letter is significant in that it contains the names and/or signatures of four former crewmen and officers of the US Steam Battery Monitor: John P. Bankhead, David R. Ellis, Samuel Dana Greene, and William F. Keeler. Greene noted on the letter the date that Ellis reported for duty and signed off; Bankhead simply wrote “Approved” and signed. Bankhead, who was captain of Monitor when it sank on December 31, 1862, was given command of Florida sometime in the winter of 1862/63 while that vessel was in New York for repairs. Bankhead requested that Greene and Keeler be assigned as his executive officer and paymaster, respectively, aboard the Florida, positions which both had held on Monitor. Keeler, in turn, requested that Ellis be assigned his steward, the same position that Ellis also had held on Monitor. -

Ward Churchill, the Law Stood Squarely on Its Head

81 Or. L. Rev. 663 Copyright (c) 2002 University of Oregon Oregon Law Review Fall, 2002 81 Or. L. Rev. 663 LENGTH: 12803 words SOCIAL JUSTICE MOVEMENTS AND LATCRIT COMMUNITY: The Law Stood Squarely on Its Head: U.S. Legal Doctrine, Indigenous Self-Determination and the Question of World Order WARD CHURCHILL* BIO: * Ward Churchill (Keetoowah Cherokee) is Chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies and Professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Colorado/Boulder. Among his numerous books are: Since Predator Came: Notes from the Struggle for American Indian Liberation (1995), A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present (1997) and, most recently, Perversions of Justice: Indigenous Peoples and Angloamerican Law (2002). SUMMARY: ... As anyone who has ever debated or negotiated with U.S. officials on matters concerning American Indian land rights can attest, the federal government's first position is invariably that its title to/authority over its territoriality was acquired incrementally, mostly through provisions of cession contained in some 400 treaties with Indians ratified by the Senate between 1778 and 1871. ... The necessity of getting along with powerful Indian [peoples], who outnumbered the European settlers for several decades, dictated that as a matter of prudence, the settlers buy lands that the Indians were willing to sell, rather than displace them by other methods. ... Under international law, discoverers could acquire land only through a voluntary alienation of title by native owners, with one exception - when they were compelled to wage a "Just War" against native people - by which those holding discovery rights might seize land and other property through military force. -

Harmon Bloodgood Is the Only Civil War Veteran Buried in the Historic Cemetery at St

By David Osborn Site Manager, St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site October 2014 Civil War Soldier Buried at St. Paul’s served with the Third Cavalry of the United States Army Harmon Bloodgood is the only Civil War veteran buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s who served in the regular United States Army, distinct from the state volunteer regiments created to meet the crisis of the Union. Ten months before Southern batteries pummeled Fort Sumter in South Carolina signaling the onset of the Civil War, Bloodgood joined the cavalry. He enlisted in June 1860 for a five year tour in the First Mounted Rifles, which had been founded in 1846. The regiment was posted on the broad stretch of the southwest, New Mexico and Texas, fighting the Comanche and other Indian nations. Policing the western frontier of American settlement was the principal responsibility of the regular American army, a small force of about 16,000 soldiers. Recruits were primarily recent immigrants, mostly from Ireland and Germany. Bloodgood, 21, reflects another channel to the regular army: young men born in America, struggling with difficult circumstances, seeking consistent livelihood and adventure. He was one of five children of a laborer living in Monmouth County, New Jersey. Bloodgood’s enlistment reports an occupation of mason. The recession and reduction in employment in the Northern states caused by the panic 1857 may have contributed to his decision to join the army. He enrolled in New York City under an Masons preparing to set bricks in the 19th century. alias, Harry Black, perhaps an indication of a strategic decision to conceal identity, a feasible practice in the 19th century before a national classification system. -

Conclusion (Volume

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Conclusion At the time of his death, Professor Lillich’s manuscript was lacking only a concluding statement of the contemporary law governing the forcible protection of nationals abroad. Although we were determined to present his work without substantive alteration, we did want this volume to be as comprehensive as possible. An editorial consensus emerged that we should append a chapter as a complementary snapshot of the law as it exists today. The following article, written by a co-editor of this volume and originally published in the Dickinson Law Review in the Spring of 2000, fit the bill. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of The Dickinson Law School of The Pennsylvania State University.† We hope that it is an appropriate punctuation mark for Professor Lillich’s research and analysis, and that it may serve as a point of departure for those scholars who will build on his impressive body of work Forcible Protection of Nationals Abroad Thomas C. Wingfield “It was only one life. What is one life in the affairs of a state?” —Benito Mussolini, after running down a child in his automobile (as reported by Gen. Smedley D. Butler in address, 1931)1 “This Government wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead.” —Theodore Roosevelt, committing the United States to the protection of Ion Perdicaris, kidnapped by Sherif Mulai Ahmed ibn-Muhammed er Raisuli (in State Department telegram, June 22nd, 1904)2 † Thomas C. Wingfield, Forcible Protection of Nationals Abroad, 104 DICK.L.REV. 493 (2000). Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner, The Dickinson School of Law of The Pennsylvania State University. -

2016 NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE CORPORATE MEMBERS 5 STAR LEVEL Bechtel Nuclear, Security & Environmental (BNI) (New in 2016) BWX Technologies, Inc

NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE TH 34 ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS L-3 COMMUNICATIONS NEWPORT NEWS SHIPBUILDING-A DIVISION OF HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES GENERAL DYNAMICS—ELECTRIC BOAT GENERAL DYNAMICS—MISSION SYSTEMS HUNT VALVE COMPANY, INC. LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION NORTHROP GRUMMAN NAVIGATION & MARITIME SYSTEMS DIVISION RAYTHEON COMPANY AECOM MANAGEMENT SERVICES GROUP BAE SYSTEMS BWX TECHNOLOGIES, INC. CURTISS-WRIGHT CORPORATION DRS TECHNOLOGIES, MARITIME AND COMBAT SUPPORT SYSTEMS PROGENY SYSTEMS, INC. TREADWELL CORPORATION TSM CORPORATION ADVANCED ACOUSTIC CONCEPTS BATTELLE BOEING COMPANY BOOZ ALLEN HAMILTON CEPEDA ASSOCIATES, INC. CUNICO CORPORATION & DYNAMIC CONTROLS, LTD. GENERAL ATOMICS IN-DEPTH ENGINEERING, INC. OCEANEERING INTERNATIONAL, INC. PACIFIC FLEET SUBMARINE MEMORIAL ASSOC., INC. SONALYSTS, INC. SYSTEMS PLANNING AND ANALYSIS, INC. ULTRA ELECTRONICS 3 PHOENIX ULTRA ELECTRONICS—OCEAN SYSTEMS, INC. 1 2016 NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE WELCOME TO THE 34TH ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM TABLE OF CONTENTS SYMPOSIUM SPEAKERS BIOGRAPHIES ADM FRANK CALDWELL, USN ................................................................................ 4 VADM JOSEPH TOFALO, USN ................................................................................... 5 RADM MICHAEL JABALEY, USN ............................................................................. 6 MR. MARK GORENFLO ............................................................................................... 7 VADM JOSEPH MULLOY, USN ................................................................................. -

Calais to Cairo

CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM Periodpostcard The Qasr al-Nil bridge, flanked by two bronze lions, which some-ex-American officers crossed to meet the Khedive in his Gezira Palace By Charles Priestley he standard answer to the question of what was the last shot fired in the T American Civil War is that it was the shot which the CSS Shenandoah fired across the bows of a Yankee whaler in the Bering Sea on June 28, 1865. On the other hand, it could plausibly be argued that the last shot of the Civil War was actually the one which killed a certain former Confederate guerrilla calling himself Mr. Howard as he was dusting a picture in his house in St Joseph, Missouri, on April 3, 1882. One candidate for the title, though, must definitely be the shot which the secretary to Benjamin Butler’s nephew fired in the best hotel in Alexandria on July 11, 1872, at a former Confederate Navy lieutenant named William Campbell, hitting him in the leg. The Alexandria in question, however, was not Alexandria, Virginia, but Alexandria, Egypt, known to the locals as Al-Iskandariyyah. So what were Campbell and some 44 other Civil War veterans, North and South, doing in Egypt in Egyptian Army uniform? To answer that, it is necessary to go back to the beginning of the 19th century, or rather slightly before, to Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798. The French occupation of Egypt lasted for only three years, but it had an enormous impact on both Western Europe and Egypt. -

SSGN Charles D

Naval War College Review Volume 59 Article 4 Number 1 Winter 2006 SSGN Charles D. Sykora Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Sykora, Charles D. (2006) "SSGN," Naval War College Review: Vol. 59 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol59/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sykora: SSGN SSGN A Transformation Limited by Legacy Command and Control Captain Charles D. Sykora, U.S. Navy A pivotal tenet of the new defense strategy is the ability to respond quickly, and thus set the initial conditions for either deterrence or the swift defeat of an aggressor....Todayweincreasingly rely on forces that are capable of both symmetric and asymmetric responses to current and potential threats....Suchswift, lethal campaigns ...clearly place a premium on having the right forces in the right place at the right time....Wemust also be able to act preemptively to prevent terrorists from doing harm to our people and our country and to prevent our enemies from threatening us, our allies, and our friends with weapons of mass destruction. ANNUAL REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT AND CONGRESS, 2003 s budget challenges put increasing pressure on the operational forces, the A ability to deter both potential adversary nations and terrorists will require the warfighting platforms of the United States to be ready to perform diverse missions in parallel. -

The Jerseyman

3rdQuarter “Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if 2006 again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN END OF AN ERA… BATTLESHIPS USS MAINE USS TEXAS US S NO USS INDIANA RTH U DAK USS MASSACHUSETTS SS F OTA LORI U DA USS OREGON SS U TAH IOWA U USS SS W YOM USS KEARSARGE U ING SS A S KENTUCKY RKAN US USS SAS NEW USS ILLINOIS YOR USS K TEXA USS ALABAMA US S S NE USS WISCONSIN U VAD SS O A KLAH USS MAINE USS OMA PENN URI SYLV USS MISSO USS ANIA ARIZ USS OHIO USS ONA NEW U MEX USS VIRGINIA SS MI ICO SSI USS NEBRASKA SSIP USS PI IDAH USS GEORGIA USS O TENN SEY US ESS USS NEW JER S CA EE LIFO USS RHODE ISLAND USS RNIA COL ORAD USS CONNECTICUT USS O MARY USS LOUISIANA USS LAND WES USS T VI USS VERMONT U NORT RGIN SS H CA IA SS KANSAS WAS ROLI U USS HING NA SOUT TON USS MINNESOTA US H D S IN AKOT DIAN A USS MISSISSIPPI USS A MASS USS IDAHO US ACH S AL USET ABAMA TS USS NEW HAMPSHIRE USS IOW USS SOUTH CAROLINA USS A NEW U JER USS MICHIGAN SS MI SEY SSO USS DELAWARE USS URI WIS CONS IN 2 THE JERSEYMAN FROM THE EDITOR... Below, Archives Manager Bob Walters described for us two recent donations for the Battleship New Jersey Museum and Memorial. The ship did not previously have either one of these, and Bob has asked us to pass this on to our Jerseyman readers: “Please keep the artifact donations coming. -

An Historical Overview of Vancouver Barracks, 1846-1898, with Suggestions for Further Research

Part I, “Our Manifest Destiny Bids Fair for Fulfillment”: An Historical Overview of Vancouver Barracks, 1846-1898, with suggestions for further research Military men and women pose for a group photo at Vancouver Barracks, circa 1880s Photo courtesy of Clark County Museum written by Donna L. Sinclair Center for Columbia River History Funded by The National Park Service, Department of the Interior Final Copy, February 2004 This document is the first in a research partnership between the Center for Columbia River History (CCRH) and the National Park Service (NPS) at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The Park Service contracts with CCRH to encourage and support professional historical research, study, lectures and development in higher education programs related to the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and the Vancouver National Historic Reserve (VNHR). CCRH is a consortium of the Washington State Historical Society, Portland State University, and Washington State University Vancouver. The mission of the Center for Columbia River History is to promote study of the history of the Columbia River Basin. Introduction For more than 150 years, Vancouver Barracks has been a site of strategic importance in the Pacific Northwest. Established in 1849, the post became a supply base for troops, goods, and services to the interior northwest and the western coast. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century soldiers from Vancouver were deployed to explore the northwest, build regional transportation and communication systems, respond to Indian-settler conflicts, and control civil and labor unrest. A thriving community developed nearby, deeply connected economically and socially with the military base. From its inception through WWII, Vancouver was a distinctly military place, an integral part of the city’s character. -

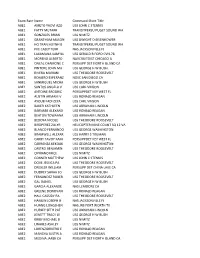

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

National Defense

National Defense of 32 code PARTS 700 TO 799 Revised as of July 1, 1999 CONTAINING A CODIFICATION OF DOCUMENTS OF GENERAL APPLICABILITY AND FUTURE EFFECT AS OF JULY 1, 1999 regulations With Ancillaries Published by the Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records Administration as a Special Edition of the Federal Register federal VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8091 Sfmt 8091 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F 1 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1999 For sale by U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402±9328 VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F ?ii Table of Contents Page Explanation ................................................................................................ v Title 32: Subtitle AÐDepartment of Defense (Continued): Chapter VIÐDepartment of the Navy ............................................. 5 Finding Aids: Table of CFR Titles and Chapters ....................................................... 533 Alphabetical List of Agencies Appearing in the CFR ......................... 551 List of CFR Sections Affected ............................................................. 561 iii VerDate 18<JUN>99 00:01 Aug 13, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX pfrm04 PsN: 183121F Cite this Code: CFR To cite the regulations in this volume use title, part and section num- ber. Thus, 32 CFR 700.101 refers to title 32, part 700, section 101. iv VerDate 18<JUN>99 04:37 Jul 24, 1999 Jkt 183121 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 8092 Sfmt 8092 Y:\SGML\183121F.XXX 183121f PsN: 183121F Explanation The Code of Federal Regulations is a codification of the general and permanent rules published in the Federal Register by the Executive departments and agen- cies of the Federal Government. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 29, No. 2, 2003

Journal of Mormon History Volume 29 Issue 2 Article 1 2003 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 29, No. 2, 2003 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2003) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 29, No. 2, 2003," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 29 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol29/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 29, No. 2, 2003 Table of Contents CONTENTS INMEMORIAM • --Dean L. May Jan Shipps, vi • --Stanley B. Kimball Maurine Carr Ward, 2 ARTICLES • --George Q. Cannon: Economic Innovator and the 1890s Depression Edward Leo Lyman, 4 • --"Scandalous Film": The Campaign to Suppress Anti-Mormon Motion Pictures, 1911-12 Brian Q. Cannon and Jacob W. Olmstead, 42 • --Out of the Swan's Nest: The Ministry of Anthon H. Lund, Scandinavian Apostle Jennifer L. Lund, 77 • --John D. T. McAllister: The Southern Utah Years, 1876-1910 Wayne Hinton, 106 • --The Anointed Quorum in Nauvoo, 1842-45 Devery S. Anderson, 137 • --"A Providencial Means of Agitating Mormonism": Parley P. Pratt and the San Francisco Press in the 1850s Matthew J. Grow, 158 • --Epilogue to the Utah War: Impact and Legacy William P. MacKinnon, 186 REVIEWS --David Persuitte, Joseph Smith and the Origins of The Book of Mormon.