An Ethnography of Youth Aging out of the Child Welfare System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gothic Trespass in the Life and Songwriting of Tennessee Blues Musician Ray Cashman

DESOLATION BLUES: THE GOTHIC TRESPASS IN THE LIFE AND SONGWRITING OF TENNESSEE BLUES MUSICIAN RAY CASHMAN Victor Bouvéron A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Folklore in the American Studies Department. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: William Ferris Glenn Hinson Crystal O’Leary-Davidson © 2017 Victor Bouvéron ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Victor Bouvéron: Desolation blues: The Gothic trespass in the life and songwriting of Tennessee blues musician Ray Cashman (Under the direction of William Ferris) This thesis explores the pervading feeling of the Gothic in the life and songwriting of Tennessee blues musician Ray Cashman. I argue that Cashman emotionally responds to the South through the framework of the Gothic to assert his identity as a white southern working- class male. As a reader, writer and performer, he trespasses the lines of race and class. The ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in Tennessee, Georgia and North Carolina between 2015 and 2017 led me to reflect on the intriguing relationship between blues, southern Gothic literature and white working-class culture in the South. The songs written by Cashman often express a feeling of desolation, bleakness and decay, invoke a sense of nostalgia for a bygone time, or describe eerie landscapes and supernatural presences. Cashman also retells southern Gothic stories, like “Snake Feast,” inspired by Harry Crews’s A Feast of Snakes. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project started the day I met Bill Ferris in Lille, France, in 2013. Bill encouraged me to apply to UNC-Chapel Hill and introduced me to the field of folklore. -

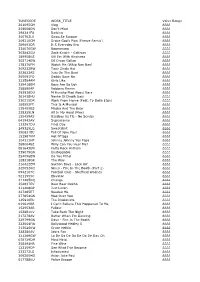

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

The Effects of Oppression on Queer Intimate Adolescent Attachment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations School of Social Policy and Practice Spring 5-17-2010 The Effects of Oppression on Queer Intimate Adolescent Attachment Cynthia Closs University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2 Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Closs, Cynthia, "The Effects of Oppression on Queer Intimate Adolescent Attachment" (2010). Doctorate in Social Work (DSW) Dissertations. 6. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations_sp2/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effects of Oppression on Queer Intimate Adolescent Attachment Abstract In America’s privileged majority, one of the primary focuses of adolescence is to establish independence from the youth’s family of origin and develop primary attachment to an intimate partner. Unlike heterosexually identified outh,y lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered and questioning (LGBTQ) youth receive limited support from society when developing their sexual orientation identity and same sex, intimate relationships. Furthermore, LGBTQ youth are exposed to an insufficient number of public, same sex relationships, have access to few supportive spaces to explore same sex sexuality and relationships, and are met with a societal understanding of relationship building that is entrenched in heterosexism. This societal oppression is concretely illustrated by the lack of consistent legal recognition of LGBTQ relationships in American society. Informed by Bowlby’s attachment theory, this qualitative research study sought to understand how experienced societal oppression of gay, bisexual, and queer male identified adolescents impacted the attachment process and attachment security of same sex relational intimacy. -

Whole Foods Market Opens in Jackson

www.mississippilink.com Vol. 20, No. 16 February 6 - 12, 2014 50¢ Forward Lookers Dr. Evie Garrett African-American Federated Club’s 28th Dennis: International History Month kicked annual luncheon honors Olympic Committee and off with ‘Living legacy of ‘Lifting As We Climb’ Mississippi history maker Freedom Out Loud’ By Ayesha K. Mustafaa Editor The XXII Olympic Winter Games begin Friday, Feb. 7, 2014, in Sochi, Russia, amid concerns of terrorist at- tacks and general complaints of un- preparedness for the arriving world athletes and audience. On January 30, Evie Garrett Den- nis, age 89, traveled from her home in Denver, Colo. to her native Mis- Fitzgerald Bynum Chambliss sissippi to visit her 98-year-old sister, retired evangelist Ozie Wattleton, and sister Ola Crockett, age 84. By Ayesha K. Mustafaa “1) To help others improve During her visit, she made the Editor Cooper-Stokes, Dominic Dantzler, Sharice Taylor and Tambra the quality of their lives, Mississippi connection to the Olym- Dennis Cherie PHOTOS BY STEPHANIE R. JONES The Forward Lookers 2) to bind together women, pics reflecting on the historic firsts Federated Club was formed young adults and youth for she achieved as an African American said Dennis. By Stephanie R. Jones City Councilwoman LaRi- when two groups under the social, moral, religious and and woman. “I got started when my fifth grade Contributing Writer ta Cooper-Stokes (Ward 3) auspices of the late Clara educational betterment and Another Mississippian linked daughter, Pia, came home and said A pro-Jacksonian, mu- brought together the group Alexander Jackson and Dr. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption. -

Sexual Violence in Popular Rap Music and Other Media

SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN POPULAR RAP MUSIC AND OTHER MEDIA Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors RAY , OLIVIA SUNDIATA Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 22:29:05 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/618766 SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN POPULAR RAP MUSIC AND OTHER MEDIA By OLIVIA SUNDIATA RAY A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelor’s Degree with Honors in Political Science THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY 2016 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Samara Klar School of Government and Public Policy Ray 2 Abstract This paper examines the prevalence of sexual violence in American media with particular focus on attitudes of sexual violence as a contribution to rape culture. Included is a content analysis of the prevalence of sexually violent lyrics in popular rap music, and a literature review of articles and studies on the effects of sexually violent media. The media discussed in the literature review includes films, television, and pornography. The relationship between the presence of sexually violent media and its impact on public opinion on sexual assault and rape proclivity are analyzed. The literature reviewed includes studies on differences in response to sexually violent media based on gender. Also included are explanation and summary of a study utilizing the excitation transfer theory and the social learning theory as they apply to the understanding of the perpetuation of rape myth acceptance based in the viewing of sexually violent media. -

How Exposure to Concentrated Disadvantage Shapes Hip-Hop

SREXXX10.1177/2332649218784964Sociology of Race and EthnicityBecker and Sweet 784964research-article2018 On Hip-Hop Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2020, Vol. 6(1) 61 –75 “What Would I Look Like?”: © American Sociological Association 2018 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649218784964 10.1177/2332649218784964 How Exposure to sre.sagepub.com Concentrated Disadvantage Shapes Hip-Hop Artists’ Connections to Community Sarah Becker1 and Castel Sweet2 Abstract Hip-hop has deep historical ties to disadvantaged communities. Resounding success in mainstream and global music markets potentially disrupts those connections. The authors use in-depth interviews with 25 self-defined rap/hip-hop artists to explore the significance of place in modern hip-hop. Bringing together historical studies of hip-hop and sociological neighborhood studies, the authors examine hip-hop artists’ community connections. Findings reveal that exposure to concentrated racial and economic disadvantage shapes how artists interpret community, artistic impact, and social responsibility. This supports the “black placemaking” framework, which highlights how black urban neighborhood residents creatively build community amid structural disadvantage. The analysis also elucidates the role specific types of physical places play in black placemaking processes. Keywords hip-hop, rap, community, black placemaking Since its inception in the 1970s in the Bronx, hip- place affects artists’ lives. Bringing together hip- hop has been tied to communities characterized by hop history and studies of neighborhood inequality, concentrated disadvantage (Chang 2005; Ogbar we ask how exposure to concentrated disadvantage 2007; Watkins 2006). As it flourished in 1980s affects artists’ community ties. Using data from a mainstream markets and quickly saturated sample of 25 southern U.S. -

A Qualitative Study of Music, Materialism, and Meaning. (2009) Directed by Dr

SUDDRETH, COURTNEY B., M.S. Hip-Hop Dress and Identity: A Qualitative Study of Music, Materialism, and Meaning. (2009) Directed by Dr. Nancy Nelson Hodges. 136 pp. Throughout the 20 th and early 21 st century, music and culture have had tremendous influence on fashion. One style in particular, known as “hip-hop” has become synonymous with sound, subculture, and style. Hip-hop music, also referred to as rap or rap music, is a style of popular music which came into existence in the United States during the late 1970s, only to become a large part of modern popular culture by the 1980s. Today hip-hop has become mainstreamed, and embraced the consumption of luxury goods and status symbols as emblems of success. Materialism is now a fundamental message within hip-hop, but this factor has received little attention in extant research. The purpose of this study is to explore its influence on hip-hop style and the significance of the messages it conveys for those involved with it. Two qualitative methods, the in-depth interview and photo-elicitation, were the primary techniques used to collect data. Combined, these two methods provided the means to reveal and explore the experiences of 12 African-American males relative to hip-hop culture. A thematic interpretation of the responses revealed a spectrum of perceptions and opinions about the significance of dress and other material objects within hip-hop, along with different degrees of internalization of hip-hop influence. Responses point to a general consensus that hip-hop has become mainstreamed today and that consequently, the messages it communicates through lyrics, videos, and other media are significantly different than those of “old school” hip-hop during its early days. -

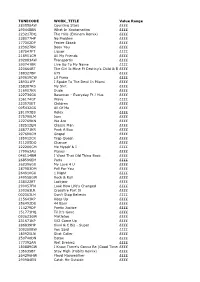

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

Innovation Dynamics of Cultural Production: Evidence in Rap Lyrics

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-7-2020 Innovation Dynamics of Cultural Production: Evidence in Rap Lyrics James M. Zumel Dumlao University of San Francisco, [email protected] Junjie Lei University of San Francisco, [email protected] Emeka Nwosu University of San Francisco, [email protected] Li Yu Oon University of San Francisco, [email protected] Tsai Ling Jeffrey Wong University of San Francisco, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Economic History Commons, Other Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Zumel Dumlao, James M.; Lei, Junjie; Nwosu, Emeka; Oon, Li Yu; Wong, Tsai Ling Jeffrey; Rising, James; and Anttila-Hughes, Jesse, "Innovation Dynamics of Cultural Production: Evidence in Rap Lyrics" (2020). Master's Theses. 1315. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author James M. Zumel Dumlao, Junjie Lei, Emeka Nwosu, Li Yu Oon, Tsai Ling Jeffrey Wong, James Rising, and Jesse Anttila-Hughes This thesis is available at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1315 Innovation Dynamics of Cultural Production: Evidence in Rap Lyrics Thesis Submission for the Masters of Science Degree in International and Development Economics James M. -

An Analysis of Kendrick Lamar's Rap Music Andrew Wellington Hollinger

ABSTRACT The Poetics of Disclosure: An Analysis of Kendrick Lamar’s Rap Music Andrew Wellington Hollinger Director: Natalie Carnes, Ph.D. In this thesis I analyze in depth Kendrick Lamar’s albums good kid, m.A.A.d city, To Pimp a Butterfly, and DAMN. Through a close reading of these albums, I examine the ways in which Lamar uses his music as a platform for prophetic music making. Lamar’s prophetic music making comes to bear three general points, corresponding to each album: first, that vices are inadequate to deal with death-anxieties and it is only Jesus Christ that gives meaning to death and life. Second, that capitalism is a tool of American Anti- Blackness and this relationship is undergirded by satanic forces. Third, that God is both a God of salvation and of damnation, so it is important to relate to God with due humility. Through these three points, I argue that Lamar’s prophetic music making can teach us something about the nature of the prophetic, that the prophet is a Divine-World discloser. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ____________________________________ Dr. Natalie Carnes, Department of Religion APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: _______________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Interim Director DATE: ________________ THE POETICS OF DISCLOSURE: AN ANALYSIS OF KENDRICK LAMAR’S RAP MUSIC A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By: Andrew Hollinger Waco, Texas May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . vii Acknowledgements . ix Dedication . xi Epigraph . xii Chapter One: Introduction . 1 1.1 Rap Music Origins .