Equal Honor and Future Glory: the Plan of Zeus in the Iliad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

PLATO's SYMPOSIUM J

50 ccn~ PLATO'S SYMPOSIUM j - - -- ________j e Library of Liberal Arts PLATO'S SYMPOSIUM Tran lated by BENJAMIN JOWETT With an Introduction by FULTON H. ANDERSON Professor of Philosophy, University of Toronto THE LIBERAL ARTS PRESS NEW YORK CONTENTS SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY .. .... ................................... ......... ... ........... 6 EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION ................... ............................................. 7 SYMPOSIUM APOLLODORUS 13 THE SPEECH OF PHAEDRUS ...... .......................... .......................... .. 19 THE SPEECH OF PAU ANIAS ................. ... ................................. ... .. 21 THE SPEECH OF ERYXIMACHUS 27 THE SPEECH OF ARISTOPHAN E .. ............................... .................. 30 THE SPEECH OF AGATHON ............ .............................................. .. 35 THE SPEECH OF SocRATES ................................ .. ................... ..... .. 39 THE SPEECH OF ALCIBIADES ................. ............... ... ........... ...... .... .. 55 8 PLATO INTROD CTION 9 crescendo, and culminates in the report by Socrates on wi dom and epistemology, upon all of which the Symposium ha bearing, learned from the "wi e" woman Diotima. are intertwined, we m ay set down briefly a few of the more general The dialogue i a "reported" one. Plato himself could not have principles which are to be found in it author's many-sided thought. been present at the original party. (What went on there was told The human soul, a cording to Plato, is es entially in motion. time and time again about Athens.) He was a mere boy when it It is li fe and the integration of living functions. A dead soul is a con took place. Nor could the narrator Apollodorus have been a guest; _lladiction in terms. Man throughout his whole nature is erotically he was too young at the time. The latter got his report from motivated. His "love" or desire i manifest in three mutually in Aristodemus, a guest at the banquet. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4

Building Community Across the Battle- Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Elmer, David. 2012. Building Community Across the Battle-Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4. In Maintaining Peace and Interstate Stability in Archaic and Classical Greece, ed. Julia Wilker, 25-48. Mainz: Verlag Antike. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33921641 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Building Community Across the Battle-Lines: The Truce in Iliad 3 and 4 Recent work on interstate relations in early Greece has produced two major revisions of established positions. The first is a welcome reassessment of Bruno Keil’s often-cited characterization of peace as “a contractual interruption of a (natural) state of war.”1 As Victor Alonso has stressed, war was only one possible mode of interaction for early Greek communities, and no more the default than either friendship or the lack of a relationship altogether.2 The second major development is represented by Polly Low’s reconsideration of the widespread assumption that “a strict line can be drawn between domestic and international life”: her work reveals the many ways in which Greek political life blurred the boundaries between intra- and inter-polis relationships.3 From a certain point of view, these two reconfigurations can be seen to be mutually reinforcing. -

Be Mindful of the Future: Information and Knowledge Management in Star Wars Tie-In Fiction

Volume 13 Spring 2017 djim.management.dal.ca | Be mindful of the future: information and knowledge management in Star Wars tie-in fiction Diana Castillo School of Information Management, Dalhousie University Abstract In the last fifty years, media franchises have been using tie-in fiction to expand their universes and tell stories outside the main source material. This paper examines how information management is used specifically in Star Wars tie-in fiction and its recent transition to using knowledge management. To start, this paper looks at the history of tie-in fiction from its roots in the 1960s to the modern day, before transitioning to the role of brand managers and editors as information managers. Then, this paper documents the history of Star Wars tie-in fiction and how information management strategies were implemented through 2014 and how it impacted the franchise’s internal continuity. Finally, this paper examines the recent move towards a unified canon and how this shift towards knowledge management has impacted storytelling. This paper concludes that while it is too early to evaluate its results, Star Wars was uniquely situated among franchises to move towards knowledge management through its prior information management efforts. Introduction universes and tell stories they may not be able to tell otherwise. Creating a well-run line In today’s entertainment environment, of tie-in fiction requires coordination between popular franchises are rarely limited to one authors, publishing houses, and the licensing type of media. They license their products company through information management. across various different formats to engage In the context of this paper, information fans and expand their footprint in popular management is defined as working with culture as much as possible. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

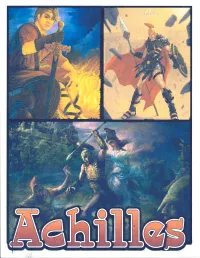

New Achilles Folder.Pdf

ffi ffi Achilles (uh-KlH-leez) was a mighty Greek hero. r. Greeks and Romans told many stories about him. The stories said that Achilles could not be harmed. He was i: ',' , ; \: i ", : : The stories also said that gods helped Achilles and other heroes. During one battle, a hero named Hector threw his spear at Achilles. The goddess Athena (uh-THEE-nuh) knocked the spear down. Then Achilles raised his spear to throw at Hector. But the god Apollo created a fog around Hector. Achilles could not see Hector. Hector ran from Achilles. As Hector ran, Athena approached him. She had i: r i i, ,. , :,: ,'. , herself as one of his brothers. So Hector stopped. Athena offered him a new spear, but it was a trick. When Hector reached for the spear, it disappeared. Achilles then caught up to Hector. He attacked and killed Hector. Achilles defeated many enemies in battle. Achilles' mother was Thetis (THEE-tuhss). She was a sea : ' . Nymphs were creatures that never grew old or died. They w€re : . Achilles' father was the human King Peleus (PEE-1ee-uhss). Peleus ruled an area of Greece called Phthia (THYE-uh). Because Achilles was part human, he would grow old and die. He was : ,, ,, . Thetis wanted to keep Achilles from dying of old age. At night, Thetis put Achilles into a fire to burn off his mortal skin. In the morning, she rubbed ambrosia (am-BRoH-zhuh) on him to heal his body. Ambrosia was the food of the gods. Achilles' mother also wanted to protect her son from harm. -

Indo-European Linguistics: an Introduction Indo-European Linguistics an Introduction

This page intentionally left blank Indo-European Linguistics The Indo-European language family comprises several hun- dred languages and dialects, including most of those spoken in Europe, and south, south-west and central Asia. Spoken by an estimated 3 billion people, it has the largest number of native speakers in the world today. This textbook provides an accessible introduction to the study of the Indo-European proto-language. It clearly sets out the methods for relating the languages to one another, presents an engaging discussion of the current debates and controversies concerning their clas- sification, and offers sample problems and suggestions for how to solve them. Complete with a comprehensive glossary, almost 100 tables in which language data and examples are clearly laid out, suggestions for further reading, discussion points and a range of exercises, this text will be an essential toolkit for all those studying historical linguistics, language typology and the Indo-European proto-language for the first time. james clackson is Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge, and is Fellow and Direc- tor of Studies, Jesus College, University of Cambridge. His previous books include The Linguistic Relationship between Armenian and Greek (1994) and Indo-European Word For- mation (co-edited with Birgit Anette Olson, 2004). CAMBRIDGE TEXTBOOKS IN LINGUISTICS General editors: p. austin, j. bresnan, b. comrie, s. crain, w. dressler, c. ewen, r. lass, d. lightfoot, k. rice, i. roberts, s. romaine, n. v. smith Indo-European Linguistics An Introduction In this series: j. allwood, l.-g. anderson and o.¨ dahl Logic in Linguistics d. -

The Iliad Book 1 Lines 1-487

The Iliad Book 1 lines 1-487. Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0134:book=1:card=1 [1] The wrath sing, goddess, of Peleus' son, Achilles, that destructive wrath which brought countless woes upon the Achaeans, and sent forth to Hades many valiant souls of heroes, and made them themselves spoil for dogs and every bird; thus the plan of Zeus came to fulfillment, from the time when first they parted in strife Atreus' son, king of men, and brilliant Achilles. [8] Who then of the gods was it that brought these two together to contend? The son of Leto and Zeus; for he in anger against the king roused throughout the host an evil pestilence, and the people began to perish, because upon the priest Chryses the son of Atreus had wrought dishonour. For he had come to the swift ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, bearing ransom past counting; and in his hands he held the wreaths of Apollo who strikes from afar, on a staff of gold; and he implored all the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, the marshallers of the people: Sons of Atreus, and other well-greaved Achaeans, to you may the gods who have homes upon Olympus grant that you sack the city of Priam, and return safe to your homes; but my dear child release to me, and accept the ransom out of reverence for the son of Zeus, Apollo who strikes from afar. -

The Marriage of Peleus & Thetis

The Marriage of Peleus & Thetis [Groton & May, Chapter 18] Peleus Thetis m. was a mortal man, the son was a sea nymph, one of of Endeis and Aeacus, king the fifty daughters of of Aegina. As a young Nereus, termed Nereids, Achilles man, Peleus and his described by Homer as, brother, Telemon were “silver-footed.” involved in the murder of their half-brother, Phocus. In exile, he married Antigone, then accidentally killed her father, Eurytion. After Antigone killed herself, Peleus again went into exile Portrait of Achilles from a Greek Black-figure vase, c. 530 BC where he met his next wife. The Nuptials The wedding was planned by Zeus (Jupiter) himself and took place on Mt. Pelion. Mortals and immortals alike were invited and all were required to bring gifts. Poseidon (Neptune) gave Peleus a pair of immortal horses, named Balius & Xanthus. The wedding is described by the Greek playwright, Euripides, in “Iphigenia at Aulis” and by the Latin poet, Catullus in poem 64. Discordia [Greek, Ερισ] The goddess of discord and the personification of strife, Discord was the only immortal not invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Angered, she threw out a golden apple inscribed with the words, “For the Fairest.” Three goddesses, Hera (Juno), Aphrodite (Venus), and Athena (Minerva), immediately begin to quarrel over the apple. Jupiter handed the decision over to the Trojan, Paris, who awards the apple to Aphrodite. Venus in turn offers him the golden apple Helen, wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta. created by Jessica Fisher, 2007 . -

People on Both Sides of the Aegean Sea. Did the Achaeans And

BULLETIN OF THE MIDDLE EASTERN CULTURE CENTER IN JAPAN General Editor: H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Vol. IV 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN ESSAYS ON ANCIENT ANATOLIAN AND SYRIAN STUDIES IN THE 2ND AND IST MILLENNIUM B.C. Edited by H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mikasa 1991 OTTO HARRASSOWITZ • WIESBADEN The Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan is published by Otto Harrassowitz on behalf of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan. Editorial Board General Editor: H.I.H. Prince Takahito Mikasa Associate Editors: Prof. Tsugio Mikami Prof. Masao Mori Prof. Morio Ohno Assistant Editors: Yukiya Onodera (Northwest Semitic Studies) Mutsuo Kawatoko (Islamic Studies) Sachihiro Omura (Anatolian Studies) Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Essays on Ancient Anatolian and Syrian studies in the 2nd and Ist millennium B.C. / ed. by Prince Takahito Mikasa. - Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 1991 (Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan ; Vol. 4) ISBN 3-447-03138-7 NE: Mikasa, Takahito <Prinz> [Hrsg.]; Chükintö-bunka-sentä <Tökyö>: Bulletin of the . © 1991 Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden This work, including all of its parts, is protected by Copyright. Any use beyond the limits of Copyright law without the permission of the publisher is forbidden and subject to penalty. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic Systems. Printed on acidfree paper. Manufactured by MZ-Verlagsdruckerei GmbH, 8940 Memmingen Printed in Germany ISSN 0177-1647 CONTENTS PREFACE