A Tale of Two Tales: Irony, Identity and the Fictions of Anthony Cronin and Brian O'nolan,’ the Parish Review: Journal of Flann O’Brien Studies 5, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Samuel Beckett (1906- 1989) Was Born in Dublin. He Was One of the Leading Dramatists and Writers of the Twentieth Century. in Hi

Samuel Beckett (1906- 1989) was born in Dublin. He was one of the leading t dramatists and writers of the twentieth century. In his theatrical images and t prose writings, Beckett achieved a spare beauty and timeless vision of human suffering, shot through with dark comedy and humour. His 1969 Nobel Prize for Literature citation praised him for ‘a body of work that in new forms of fiction and the theatre has transmuted the destitution of modern man into his exaltation’. A deeply shy and sensitive man, he was often kind and generous both to friends and strangers. Although witty and warm with his close friends, he was intensely private and refused to be interviewed or have any part in promoting his books or plays. Yet Beckett’s thin angular countenance, with its deep furrows, cropped grey hair, long beak- like nose and gull-like eyes is one of the iconic faces of the twentieth century. Beckett himself acknowledged the impression his Irish origin left on his imagination. Though he spent most of his life in Paris and wrote in French as well as English, he always held an Irish passport. His language and dialogue have an Irish cadence and syntax. He was influenced by Becke many of his Irish forebears, Jonathan Swift, J.M. Synge, William and Jack Butler Yeats, and particularly by his friend and role model, James Joyce. When a journalist asked Beckett if he was English, he replied, simply, ‘Au contraire’. Family_ Beckett was born on Good Friday, 13th April 1906, in the affluent village of Foxrock, eight miles south of Dublin. -

The 'Nothing-Could-Be-Simpler Line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry

The 'nothing-could-be-simpler line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry Brearton, F. (2012). The 'nothing-could-be-simpler line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry. In F. Brearton, & A. Gillis (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Poetry (pp. 629-647). Oxford University Press. Published in: The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Poetry Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:26. Sep. 2021 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 04/19/2012, SPi c h a p t e r 3 8 ‘the nothing-could- be-simpler line’: form in contemporary irish poetry f r a n b r e a r t o n I I n ‘ Th e Irish Effl orescence’, Justin Quinn argues in relation to a new generation of poets from Ireland (David Wheatley, Conor O’Callaghan, Vona Groarke, Sinéad Morrissey, and Caitríona O’Reilly among them) that while: Northern Irish poetry, in both the fi rst and second waves, is preoccupied with the binary opposition of Ireland and England . -

Beckett and His Biographer: an Interview with James Knowlson José Francisco Fernández (Almería, Spain)

The European English Messenger, 15.2 (2006) Beckett and His Biographer: An Interview with James Knowlson José Francisco Fernández (Almería, Spain) James Knowlson is Emeritus Professor of French at the University of Reading. He is also the founder of the International Beckett Foundation (previously the Beckett Archive) at Reading, and he has written extensively on the great Irish author. He began his monumental biography, Damned to Fame:The Life of Samuel Beckett (London: Bloomsbury, 1996) when Beckett was still alive, and he relied on the Nobel Prize winner’s active cooperation in the last months of his life. His book is widely acknowledged as the most accurate source of information on Beckett’s life, and can only be compared to Richard Ellmann’s magnificent biography of James Joyce. James Knowlson was interviewed in Tallahassee (Florida) on 11 February 2006, during the International Symposium “Beckett at 100: New Perspectives” held in that city under the sponsorship of Florida State University. I should like to express my gratitude to Professor Knowlson for giving me some of his time when he was most in demand to give interviews in the year of Beckett’s centennial celebrations. José Francisco Fernández JFF: Yours was the only biography on or even a reply to the earlier biography of authorised by Beckett. That must have been Deirdre Bair. It needs to stand on its own two a great responsibility. Did it represent at any feet. And I read with great fascination the time a burden? Knowing that what you wrote biography of Deirdre Bair and have never said would be taken as ‘the truth’. -

The Astray Belonging—The Perplexity of Identity in Paul Muldoon's Early

International Conference on Humanities and Social Science (HSS 2016) The Astray Belonging—The Perplexity of Identity in Paul Muldoon’s Early Poems Jing YAN Sichuan Agricultural University, Dujiangyan, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China Keywords: Paul Muldoon, Northern Ireland, Identity, Perplexity. Abstract. As a poet born in a Catholic family in Northern Ireland but deeply influenced by the British literary tradition, Paul Muldoon’s identity is obviously multiple and complex especially from 1970s to 1980s when Northern Ireland was going through the most serious political, religious and cultural conflicts, all of which were unavoidably reflected in the early poems of Paul Muldoon. This thesis attempts to study the first four anthologies of Paul Muldoon from the perspective of Diaspora Criticism in Cultural Studies to discuss the issues of identities reflected in Muldoon’s poems. Obviously, the perplexity triggered by identities is not only of the poet himself but also concerning Northern Irish issues. Muldoon’s poems relating cultural identities present the universal perplexity of Irish identity. Introduction While Ireland is a small country in Western Europe, this tiny piece of magical land has given birth to countless literary giants. From Jonathan Swift and Richard Sheridan in the 18th century, to Oscar Wilde in the 19th century and all the way to James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney in the 20th century, there are countless remarkable Irish writers who help to build the reputation of Irish literature. Since 1960s or 1970s, the rise of Irish poetry began to draw world attention, particularly after poet Seamus Heaney won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, Following Heaney, the later poets in Ireland are also talented in poetic creation, of whom ,the 2003 Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Muldoon is undoubtedly a prominent representative. -

Soup of the Day Chowder of the Day Homemade Chili Irish Goat Cheese Salad Spicy Chicken Salad Smoked Pheasant Salad Smoked Salmo

Soup of the Day Irish Goat Cheese Salad Smoked Pheasant Salad Served with brown bread & Irish butter Mixed greens tossed with sundried Smoked pheasant with rocket, Cup 3. Bowl 6. tomatoes, roasted red pepper, cherry shaved Irish cheddar, dried fruit, tomatoes, candied nuts crumbled candied nuts, red onion & shaved Chowder of the Day goat cheese, topped with a warm goat carrot 12. Served with brown bread & Irish butter cheese disc 10. Cup 3. Bowl 6. Smoked Salmon Salad Spicy Chicken Salad Chopped romaine lettuce, tomato, Homemade Chili Chopped romaine, bacon, tomato, Irish cheddar, peppers, red onion , Served with corn bread, scallions, cheese & scallions cup fried chicken tossed in blue cheese topped with slices of Irish oak Cup 3. Bowl 6. and buffalo sauce 12. smoked salmon 14. Frittatas Choice of smoked salmon & Irish cheddar, Irish sausage & bacon, shrimp & spinach or vegetarian. Served with choice of fruit, side salad or Sam’s spuds 12. Irish Breakfast Dalkey Benedict Mitchelstown Eggs Two bangers, two rashers, two black & white Slices of oak smoked salmon on top of two An Irish muffin with sautéed spinach, pudding, potato cake, eggs & baked beans, poached eggs with a potato cake base and poached eggs and hollandaise sauce 12. with Beckett’s brown bread 15. topped with hollandaise sauce 12. Tipperary Tart Baileys French Toast Roscrea Benedict A quiche consisting of leeks and Irish Cashel Brioche with a mango chutney and syrup. An Irish muffin topped with poached eggs blue cheese in a pastry shell. Served with a Served with choice of fruit or Sam’s spuds 12. -

Irish Divorce/Joyce's

Irish Divorce/Joyce’s Ulysses Irish Divorce/ Joyce’s Ulysses Peter Kuch Peter Kuch University of Otago Dunedin, New Zealand ISBN 978-1-349-95187-1 ISBN 978-1-137-57186-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57186-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939123 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- tional affiliations. Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Field Day Revisited (II): an Interview with Declan Kiberd1

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 33.2 September 2007: 203-35 Field Day Revisited (II): An Interview with Declan Kiberd1 Yu-chen Lin National Sun Yat-sen University Abstract Intended to address the colonial crisis in Northern Ireland, the Field Day Theatre Company was one of the most influential, albeit controversial, cultural forces in Ireland in the 1980’s. The central idea for the company was a touring theatre group pivoting around Brian Friel; publications, for which Seamus Deane was responsible, were also included in its agenda. As such it was greeted by advocates as a major decolonizing project harking back to the Irish Revivals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its detractors, however, saw it as a reactionary entity intent on reactivating the same tired old “Irish Question.” Other than these harsh critiques, Field Day had to deal with internal divisions, which led to Friel’s resignation in 1994 and the termination of theatre productions in 1998. Meanwhile, Seamus Deane persevered with the publication enterprise under the company imprint, and planned to revive Field Day in Dublin. The general consensus, however, is that Field Day no longer exists. In view of this discrepancy, I interviewed Seamus Deane and Declan Kiberd to track the company’s present operation and attempt to negotiate among the diverse interpretations of Field Day. In Part One of this transcription, Seamus Deane provides an insider’s view of the aspirations, operation, and dilemma of Field Day, past and present. By contrast, Declan Kiberd in Part Two reconfigures Field Day as both a regional and an international movement which anticipated the peace process beginning in the mid-1990’s, and also the general ethos of self-confidence in Ireland today. -

Downloaded from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil Na Héireann, Corcaigh

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Author(s) Lawlor, James Publication date 2020-02-01 Original citation Lawlor, J. 2020. A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, James Lawlor. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10128 from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork A Cultural History of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Thesis presented by James Lawlor, BA, MA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork The School of English Head of School: Prof. Lee Jenkins Supervisors: Prof. Claire Connolly and Prof. Alex Davis. 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 4 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 6 List of abbreviations used ................................................................................................... 7 A Note on The Great -

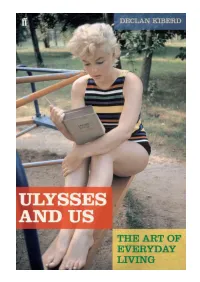

Ulysses and Us

Ulysses and Us The Art of Everyday Living declan kiberd First published in 2009 by Faber and Faber Ltd Bloomsbury House 74–77 Great Russell Street London wc1b 3da Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd Printed in England by CPI Mackays, Chatham All rights reserved © Declan Kiberd, 2009 The right of Declan Kiberd to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978–0–571–24254–2 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 In memory of John McGahern ‘Níl ann ach lá dár saol’ Contents Acknowledgements ix Note on the Text xi How Ulysses Didn’t Change Our Lives 3 How It Might Still Do So 16 Paralysis, Self-Help and Revival 32 1 Waking 41 10 Wandering 153 2 Learning 53 11 Singing 168 3 Thinking 64 12 Drinking 181 4 Walking 77 13 Ogling 193 5 Praying 89 14 Birthing 206 6 Dying 100 15 Dreaming 222 7 Reporting 113 16 Parenting 237 8 Eating 124 17 Teaching 248 9 Reading 137 18 Loving 260 Ordinary People’s Odysseys 277 Old Testaments and New 296 Depression and After: Dante’s Comedy 313 Shakespeare, Hamlet and Company 331 Conclusion: The Long Day Fades 347 Notes 359 Index 381 vii Acknowledgements For almost thirty years the students of University College Dublin have been teaching me about their famous fore- runner. -

The IRISH Seminar 2021

The IRISH Seminar 2021 Faculty Lead: Barry McCrea Format: Webinar* Please note that all times are listed in EST. Tuesday 8 June 9am Welcome & Introductions by Patrick Griffin & Barry McCrea 9.30am-10.30am Opening Roundtable: The State of Irish History Break Panel: Carole Holohan (Trinity College Dublin) 11.00am – 12.00pm Anne Dolan (Trinity College Dublin) Enda Delaney (University of Edinburgh) Ian McBride (Hertford College, Oxford) Moderator: Patrick Griffin (Notre Dame) 2-3pm Poetry Reading: Doireann Ní Gríofa Moderator: Brian Ó Conchubhair Wednesday 9 June Irish Studies from austerity to pandemic Editors of the Routledge International Handbook of Irish Studies (2021) in conversation with selected contributors. 9.00-9.15am Introduction with Renée Fox (University of California, Santa Cruz), Mike Cronin (Boston College) and Brian Ó Conchubhair (Notre Dame) 9.15-10.00am Eric Falci (University of California, Berkeley): Aesthetics of Irish poetry Sarah Townsend (University of New Mexico): Race in Ireland & Irish America. 10.00-10.15am Break 10.15-11.00am Claire Bracken (Union College): Gender and Irish Studies Nessa Cronin (NUI Galway): Environmentalities & the Anthropocene Maggie O'Neill (NUI Galway): The Ageing body in Irish Literature 11.00-11.15am Break 11.15-12.00pm Discussion and Q&A with panellists and participants Thursday 10 June Digital Humanities & Irish Studies 9.00-9.25 Beyond 2022 project overview. 9.25-10.00 Case Study 1: Medieval Ireland by Lynn Kigallon (Trinity College Dublin) 10.00-10.30 Break 10.30-11.00 Case Study 2: Eighteenth Century Ireland by Tim Murtagh (Trinity College Dublin) 11.00-11.15 Break 11.15-12.00 Discussion Friday 11 June Black Ireland Please note times for this seminar are subject to change** 9am Introduction by Chante Mouton Kinyon (Notre Dame) 9.15am Korey Garibaldi (Notre Dame) with Colm Toibin (Columbia): Culture and Racial Cosmopolitanism 10.15am Comfort break 10.45-11.45 Chante Mouton Kinyon with Colm Tóibín: Stranger in the Village 12:00-12.30 Discussion. -

Irish Copyright Licensing Agency CLG Mandated Author Rightholders

Irish Copyright Licensing Agency CLG Mandated Author Rightholders Author Rightholder Name Ann Sheppard Adrian White Anna Donovan Adrienne Neiland Anna Heffernan Aidan Dundon Anna McPartlin The Estate of Aidan Higgins Anne Boyle Aidan O'Sullivan Anne Chambers Aidan P. Moran Anne Deegan Aidan Seery Anne Enright Aileen Pierce Anne Fogarty Áine Dillon Anne Gormley Áine Francis- Stack Anne Haverty Áine Ní Charthaigh Anne Holland Áine Uí Eadhra Anne Jones Aiveen McCarthy Anne Marie Herron Alan Dillon Anne Potts Alan Kramer Anne Purcell Alan Monaghan The Estate of Anne Schulman Alan O'Day Annetta Stack Alannah Hopkin Annie West Alexandra O'Dwyer Annmarie McCarthy Alice Coghlan Anthea Sullivan Alice Taylor Anthony Cronin Alison Mac Mahon Anthony J Leddin Alison Ospina Anthony Summers Allen Foster Antoinette Walker Allyson Prizeman Aodán Mac Suibhne Amanda Clarke Arlene Douglas Amanda Hearty Arnaud Bongrand Andrew B. Lyall Art Cosgrove Andrew Breeze Art J Hughes Andrew Carpenter Art Ó Súilleabháin Andrew Loxley Arthur McKeown Andrew Purcell Arthur Mitchell Andy Bielenberg Astrid Longhurst Angela Bourke Aubrey Dillon Malone Angela Doyle Aubrey Flegg Angela Griffin The Estate of Augustine Martin Angela Marie Burt Austin Currie Angela Rickard Avril O'Reilly Angela Wright Barry Brunt The Estate of Angus McBride Barry McGettigan The Estate of Anita Notaro Bart D. Daly Ann Harrow The Estate of Basil Chubb Ann O Riordan Ber O'Sullivan 1 Irish Copyright Licensing Agency CLG Mandated Author Rightholders Bernadette Andresso Brian Lennon Bernadette Bohan Brian Leonard Bernadette Cosgrove Brian McGilloway Bernadette Cunningham The Estate of Brian O'Nolan Bernadette Matthews Brian Priestley Bernadette McDonald Brianóg Brady Dawson Bernard Horgan Bríd Nic an Fhailigh Bernard MacLaverty Bried Bonner Bernard Mulchrone The Estate of Brigid Brophy Bernie McDonald Brigid Laffan Bernie Murray-Ryan Brigid Mayes Bernie Ruane Brigitte Le Juez Betty Stoutt Bronwen Braun Bill Rolston Bryan M.E.