Danaher Corporation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DANAHER CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

DANAHER CORP /DE/ FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 3/10/2004 For Period Ending 12/31/2003 Address 2099 PENNSYLVANIA AVE N.W., 12TH FLOOR WASHINGTON, District of Columbia 20006 Telephone 202-828-0850 CIK 0000313616 Industry Scientific & Technical Instr. Sector Technology Fiscal Year 12/31 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2003 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 1-8089 DANAHER CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 59-1995548 (State of incorporation) (I.R.S.Employer Identification number) 2099 Pennsylvania Ave. N.W., 12 th Floor Washington, D.C. 20006 -1813 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 202-828-0850 Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of Exchanges on which registered Common Stock $.01 par Value New York Stock Exchange, Inc. Pacific Stock Exchange, Inc. Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

2019 Annual Report

1984 2019 2019 MARKED DANAHER’S 35TH ANNIVERSARY To honor this milestone, the front cover of this year's annual report features the original Danaher logo and bright blue color palette. We proudly celebrate our company's history as the prelude to a 35 future filled with opportunity. By living our core values of building the best team, continuously improving, “ listening to our customers every day and driving innovation, we ultimately deliver long-term shareholder value.” Thomas P. Joyce, Jr. Financial Operating Highlights (dollars in millions except per share data and number of associates) 2019 2018 Sales $ 17,911.1 $ 17,048.5 Operating Profit $ 3,269.4 $ 3,055.1 Net Earnings $ 2,432.3 $ 2,406.3 Net Earnings Per Share (diluted) $ 3.26 $ 3.39 Operating Cash Flow $ 3,657.4 $ 3,644.0 Investing Cash Flow $ (1,166.1) $ (2,873.9) Financing Cash Flow $ 16,589.9 $ (797.4) Capital Expenditures $ (635.5) $ (583.5) Capital Disposals $ 12.8 $ 6.3 Free Cash Flow (Operating Cash Flow less Capital Expenditures plus Capital Disposals) $ 3,034.7 $ 3,066.8 Number of Associates 60,000 58,000 Total Assets* $ 62,081.6 $ 47,832.5 Total Debt ** $ 21,729.1 $ 9,740.3 Stockholders’ Equity $ 30,281.9 $ 28,226.7 Total Capitalization (Total Debt plus Stockholders’ Equity) $ 52,011.0 $ 37,967.0 * 2018 data includes both continuing and discontinued operations ** Long-Term Debt ($21,516.7 for 2019 and $9,688.5 for 2018) plus Notes Payable and Current Portion of Long-Term Debt ($212.4 for 2019 and $51.8 for 2018) All financial data set forth in this annual report relates solely to continuing operations unless otherwise indicated. -

HW&Co. Industry Reader Template

EUROPEAN UPDATE INDUSTRY UPDATE │ SUMMER 2015 www.harriswilliams.com www.harriswilliams.de Harris Williams & Co. Ltd is a private limited company incorporated under English law having its registered office at 5th Floor, 6 St. Andrew Street, London EC4A 3AE, UK, registered with the Registrar of Companies for England and Wales under company number 7078852. Directors: Mr. Christopher Williams, Mr. Ned Valentine, Mr. Paul Poggi and Mr. Thierry Monjauze, authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Harris Williams & Co. Ltd Niederlassung Frankfurt (German branch) is registered in the Commercial Register (Handelsregister) of the Local Court (Amtsgericht) of Frankfurt am Main, Germany, under registration number HRB 96687, having its business address at Bockenheimer Landstrasse 33-35, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Permanent Representative (Ständiger Vertreter) of the Branch Niederlassung: Mr. Jeffery H. Perkins. EUROPEAN UPDATE INDUSTRY UPDATE │ SUMMER 2015 HARRIS WILLIAMS & CO. CONTACTS CONTENTS Thierry Monjauze Managing Director QUARTERLY QUICK READ 63 Brook Street London W1K 4HS United Kingdom EUROPEAN ECONOMIC CLIMATE Phone: +44 20 7518 8901 [email protected] EUROPEAN M&A ENVIRONMENT Red Norrie Managing Director EUROPEAN INBOUND M&A ENVIRONMENT 63 Brook Street London W1K 4HS United Kingdom AEROSPACE, DEFENCE & GOVERNMENT SERVICES Phone: +44 20 7518 8906 [email protected] BUSINESS SERVICES Jeffery Perkins Managing Director CONSUMER Bockenheimer Landstr. 33-35 60325 Frankfurt Germany ENERGY & POWER Phone: +49 69 3550638 00 [email protected] HEALTHCARE & LIFE SCIENCES LONDON OFFICE 63 Brook Street INDUSTRIALS London W1K 4HS United Kingdom Phone: +44 20 7518 8900 TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA & TELECOM FRANKFURT OFFICE Bockenheimer Landstrasse TRANSPORTATION & LOGISTICS 33-35 60325 Frankfurt am Main Germany FEATURED THEME Phone: +49 69 3650638 00 FEATURED THEME – MOMENTUM IN ACQUISITIONS BY STRATEGIC BUYERS1 . -

Danaher—The Making of a Conglomerate

UVA-BP-0549 Rev. Dec. 9, 2013 DANAHER—THE MAKING OF A CONGLOMERATE After joining Danaher Corporation (Danaher) in 1990, CEO H. Lawrence Culp helped transform the company from an $845 million industrial goods manufacturer to a $12.6 billion global conglomerate. Danaher’s 25-year history of acquisition-driven expansion had produced healthy stock prices as well as above average growth and profitability for more than 20 years (Exhibits 1 and 2); however, Wall Street had questioned the scalability of the company’s corporate strategy and its reliance on acquisitions since mid-2007. Prudential Equity Group had downgraded Danaher to underweight status, citing concerns over its inadequate organic growth. Company History (1984–91) In 1984, Steven and Mitchell Rales had formed Danaher by investing in undervalued manufacturing companies. The Rales brothers built Danaher by targeting family-owned or privately held companies with established brands, proprietary technology, high market share, and room for improvement in operating performance. Averaging 12 acquisitions per year (Exhibit 3), by 1986, Danaher was listed as a Fortune 500 company and held approximately 600 small and midsize companies. Acquisitions were concentrated in four areas: precision components (Craftsman hand tools), automotive and transportation (mechanics’ tools, tire changers), instrumentation (retail petrol pumps), and extruded products (vinyl siding). As these businesses grew and gained critical mass, Danaher used the term business unit to define any collection of similar businesses. Exhibit 4 provides a brief history of each of the original four businesses. Restructuring George Sherman was brought from Black & Decker as Danaher’s CEO following the crash of the LBO market in 1988. -

Severance Agreement Includes a Release of Claims and Non-Compete Provisions

severance agreement includes a release of claims and non-compete provisions. It is described below under “Payments Upon Termination, Disability or Death.” Comparative Compensation For comparative purposes, we generally focus on a group of publicly traded companies. We believe these comparison companies are representative of the types of firms with which we compete for executive talent, inasmuch as a number of the comparison companies operate one or more lines of business that compete with us. We believe we also compete for talent with private equity and other non-public companies, since the core skills and responsibilities required in our executives are generally not unique to our industries or markets. Other major factors we use to select this peer group include revenues and net income and market capitalization. The peer companies include: The Black & Decker Corporation M.D.C. Holdings, Inc. Danaher Corporation Newell Rubbermaid Inc. Dover Corporation NVR, Inc. D.R. Horton, Inc. PulteGroup, Inc. Emerson Electric Co. The Ryland Group, Inc. Fortune Brands, Inc. The Sherwin-Williams Company The Home Depot, Inc. SPX Corporation Illinois Tool Works Inc. The Stanley Works ITT Corporation Textron Inc. KB Home Toll Brothers, Inc. Lennar Corporation United Technologies Corporation Lowe’s Companies, Inc. 3M Company For each executive officer, we compare the overall competitiveness of total compensation, as well as each major component of compensation and the mix of components, with executives in comparable positions at our peer companies. Generally, when considering the competiveness of our total compensation packages to those of our peers, the Committee gives the most weight to information regarding the median level of base salary, target annual cash compensation, and target total compensation. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Segmentation Voice of the Customer Dynamic Resource Allocation Brand Management Policy Deployment MEASURING Risk Management Value Selling Innovation Talent SUCCESS Accelerated Product Development Sales Force Initiatives Emerging Markets Digital Marketing DBS 2010 ANNUAL REPORT In 2010, Danaher updated reporting segments to reflect the evolution of our business to a science and technology company. We now report results in five business segments: Test & Measurement; Environmental; Life Sciences & Diagnostics; Dental; and Industrial Technologies. TEST & MEASUREMENT Our Test & Measurement segment is a leading, global provider of electronic measurement instruments and monitoring, management and optimization tools for communications and enterprise networks and related services. Our products are used in the design, development, manufacture, installation, deployment and operation of electronics equipment and communications networks and services. Customers for our products and services include manufacturers of electronic instruments; service, installation and maintenance professionals; network equipment manufacturers who design, develop, manufacture and install network equipment and service providers who implement, maintain and manage communications networks and services. Also included in our Test & Measurement segment are our mobile tool and wheel service businesses. Financial Operating Highlights 2010 2009 (dollars in thousands except per share data and number of associates) Sales $ 13,202,602 $ 11,184,938 Operating profit -

2018 Annual Report

2018 Annual Report Danaher 2018 Annual Report Financial Operating Highlights (dollars in millions except per share data and number of associates) 2018 2017 Sales $ 19,893.0 $ 18,329.7 Operating Profit $ 3,403.8 $ 2,990.4 Net Earnings $ 2,650.9 $ 2,469.8 Net Earnings Per Share (diluted) $ 3.74 $ 3.50 Operating Cash Flow $ 4,022.0 $ 3,477.8 Investing Cash Flow $ (2,949.4) $ (843.4) Financing Cash Flow $ (797.4) $ (3,098.5) Capital Expenditures $ (655.7) $ (619.6) Capital Disposals $ 6.3 $ 32.6 Free Cash Flow (Operating Cash Flow less Capital Expenditures plus Capital Disposals) $ 3,372.6 $ 2,890.8 Number of Associates 71,000 67,000 Total Assets $ 47,832.5 $ 46,648.6 Total Debt * $ 9,740.3 $ 10,522.1 Stockholders’ Equity $ 28,226.7 $ 26,367.8 Total Capitalization (Total Debt plus Stockholders’ Equity) $ 37,967.0 $ 36,889.9 * Long-Term Debt ($9,688.5 for 2018 and $10,327.4 for 2017) plus Notes Payable and Current Portion of Long-Term Debt ($51.8 for 2018 and $194.7 for 2017) All financial data set forth in this annual report relates solely to continuing operations unless otherwise indicated. 2018 Annual Report Dear Shareholders, As I begin my 30th year at Danaher, it is humbling to reflect on what our team has achieved over that time and exciting to think about the opportunities that still lie ahead. Financially and strategically, 2018 was an outstanding year. With the Danaher Business System (DBS) as our driving force, we strengthened our footholds in attractive, fast-growing markets and enhanced our competitive positions. -

2011 Cycle 3 Leaps Introduction

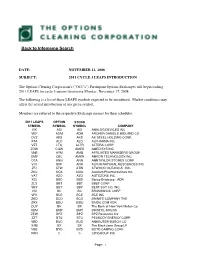

TOBack: to Infomemo SearchALL CLEARING MEMBERS #25104 FROM: FRANCES KRISCHUNAS NATIONAL OPERATIONS DATE: NOVEMBER 12, 2008 SUBJECT: 2011 CYCLE 3 LEAPS INTRODUCTION The Options Clearing Corporation's ("OCC's") Participant Options Exchanges will begin trading 2011 LEAPS for cycle 3 options beginning Monday, November 17, 2008. The following is a list of those LEAPS symbols expected to be introduced. Market conditions may affect the actual introduction of any given symbol. Members are referred to the respective Exchange memos for their schedules. 2011 LEAPS OPTION STOCK SYMBOL SYMBOL SYMBOL COMPANY VIK ADI ADI ANALOG DEVICES INC VEF ADM ADM ARCHER DANIELS MIDLAND CO OVZ AKS AKS AK STEEL HOLDING CORP. XTA ALO ALO ALPHARMA INC VZT LTQ ALTR ALTERA CORP ZOW CQW AMED AMEDISYS INC VNB AYM AMG AFFILIATED MANAGERS GROUP OMY QEL AMKR AMKOR TECHNOLOGY,INC. OTA ANN ANN ANNTAYLOR STORES CORP VJV BNF ANR ALPHA NATURAL RESOURCES INC ZFJ ATW ATW ATWOOD OCEANICS , INC ZKU UQX AUXL Auxilium Pharmaceuticals Inc. VAT AZO AZO AUTOZONE INC. XSJ BBD BBD Banco Bradesco - ADR ZLS BBT BBT BB&T CORP VBY BBY BBY BEST BUY CO. INC. VXI BC BC BRUNSWICK CORP VFK BCE BCE BCE INC ZKO BCO BCO BRINK'S COMPANY THE ZRX BDU BIDU BAIDU.COM ADR OUY BK BK The Bank of New York Mellon Co VBM BMY BMY BRISTOL-MYERS ZEW BPZ BPZ BPZ Resources Inc ZZT BTU BTU PEABODY ENERGY CORP. VBD BUD BUD ANHEUSER-BUSCH CO XJM BX BX The Blackstone Group LP VBB BYD BYD BOYD GAMING CORP. VRN C C CITIGROUP INC Page: 1 2011 LEAPS OPTION STOCK SYMBOL SYMBOL SYMBOL COMPANY OYH CAG CAG CONAGRA FOODS OCJ CAH CAH CARDINAL HEALTH INC OVJ CAL CAL CONTINENTAL AIRLINES CLB ZCB CBS CBS CBS Corporation CL B ZBK CCJ CCJ CAMECO CORPORATION VCM CQL CENX CENTURY ALUMINUM COMPANY ZJZ CHL CHL China Mobile Limited ZXN CMC CMC COMMERCIAL METALS COMPANY OX CNM CME CME Group Inc ZTK QCY CMED CHINA MEDICAL TECH INC SPON ADR VBE CMI CMI CUMMINS INC. -

Billing Code: 6750-01S

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/03/2015 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2015-27992, and on FDsys.gov BILLING CODE: 6750-01S Federal Trade Commission Granting Of Request for Early Termination Of The Waiting Period Under The Premerger Notification Rules Section 7A of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C.§ 18a, as added by Title II of the Hart-Scott- Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, requires persons contemplating certain mergers or acquisitions to give the Federal Trade Commission and the Assistant Attorney General advance notice and to wait designated periods before consummation of such plans. Section 7A(b)(2) of the Act permits the agencies, in individual cases, to terminate this waiting period prior to its expiration and requires that notice of this action be published in the Federal Register. The following transactions were granted early termination -- on the dates indicated -- of the waiting period provided by law and the premerger notification rules. The listing for each transaction includes the transaction number and the parties to the transaction. The grants were made by the Federal Trade Commission and the Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice. Neither agency intends to take any action with respect to these proposed acquisitions during the applicable waiting period. 1 Early Terminations Granted March 1, 2015 thru September 30, 2015 03/03/2015 20150580 G FMR LLC ; The Guardian Life Insurance Company of America ; FMR LLC 03/06/2015 20150597 G Accenture plc ; Robert E LaRose Revocable Trust ; Accenture plc 20150614 G Hitachi Ltd. -

Investor Relations | Snap-On Incorporated

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended January 3, 2004 [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 1-7724 SNAP-ON INCORPORATED (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 39-0622040 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 10801 Corporate Drive, Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin 53158-1603 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (262) 656-5200 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of exchange on which registered Common stock, $1 par value New York Stock Exchange Preferred stock purchase rights New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months, and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes [X] No [ ] Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of the registrant’s knowledge, in a definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

Interim Financial Statements DESJARDINS Etfs

Interim Financial Statements DESJARDINS ETFs As at June 30, 2021 INTERIM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS (UNAUDITED) | NOTICE The following Desjardins ETFs’ Interim Financial Statements have not been subject to a review by the Funds’ external auditors. The Desjardins Exchange Traded Funds are not guaranteed, their value fluctuates frequently and their past performance is not indicative of their future returns. Commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with an investment in exchange traded funds. Please read the prospectus before investing. Desjardins Global Asset Management Inc. is the manager and portfolio manager of the Desjardins Exchange Traded Funds. Desjardins is a trademark owned by the Fédération des caisses Desjardins du Québec used under license. DESJARDINS RI GLOBAL MULTIFACTOR — FOSSIL FUEL RESERVES FREE ETF STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION (Unaudited) STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME (Unaudited) AS AT JUNE 30 DECEMBER 31 PERIODS ENDED JUNE 30 2021 2020 2021 2020 $ $ $ $ Income ASSETS Dividends 135,434 101,105 Current Assets Foreign exchange gain (loss) on cash (4,526) 24,199 Cash 84,668 74,707 Revenue from securities lending activities 162 61 Investments at fair value through profit or loss (FVTPL) 14,318,475 10,020,095 Changes in fair value: Investments at fair value through profit or loss (FVTPL) Net realized gain (loss) on investments 461,159 325,797 pledged as collateral 270,863 95,612 Net unrealized gain (loss) on investments 467,105 49,851 Receivable for investments sold 7,943 33,687 1,059,334 501,013 Interest, -

2018 Participating Organizations

2018 Participating Organizations 3M Company Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Inc. 7‐Eleven, Inc. Alerus Financial Corporation A. O. Smith Corporation Alfa Laval, Inc. A. O. Water Treatment Alfa Mutual Insurance Company A123 Systems LLC All Nippon Airways Co., Ltd. AAA Club Alliance Inc. Allegis Group AAA National Office Alliance Data Systems ‐ Card Services AAA Northern California, Nevada and Utah Alliant Energy Corporation Aaron's Inc. Allianz Asset Management of America L.P. Abbott Laboratories ‐ Nutrition Allied Motion Technologies, Inc. Abloy Security, Inc. Allina Health System ABRA Auto Body & Glass Allina Health System ‐ New Ulm Medical Center Abt Associates, Inc. Allnex Group Accenture, Inc. Allnex USA Inc. Accolade Ally Financial, Inc. Accolade Wines North America, Inc. Alorica AccorHotels NA Alto‐Shaam ACH Food Companies, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. ACUITY Alyeska Pipeline Service Company Acushnet Holdings Corporation Alys Beach Adidas America, Inc. Amazing Grass Adient US LLC Amazon.com ADT, LLC Amcor Rigid Plastics Advance Auto Parts, Inc. Amedisys, Inc. Advance Local AMERICA CENTRAL CORPORATION Advanced Drainage Systems, Inc. American Airlines Group, Inc. Adventist Chippewa Valley Hospital American Augers Adventist Health System American Bureau of Shipping Adventist Health System GA Inc. American Century Investments Advocate Health Care American Century Investments ‐ CA Aegis Therapies, LLC American Dental Partners, Inc. AET Inc., Ltd. ‐ AET Offshore Services, Inc. American Enterprise Group, Inc. AET, Inc., Ltd. American Family Insurance Aetna, Inc. American Financial Group, Inc. Affinion Group Holdings, Inc. American Financial Group, Inc. ‐ Great American Financial Aflac, Inc. Resources, Inc. Aflac, Inc. ‐ Communicorp, Inc. American Financial Group, Inc. ‐ Great American Insurance Agero, Inc. Group AgFirst Farm Credit Bank American Financial Group, Inc.