Now You See It, Now You Don't

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

I H611 Oween Iv

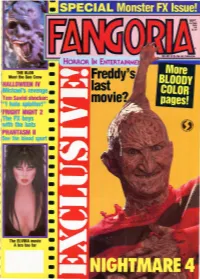

THE BLOB Meet the Goo Crew I H611 OWEEN IV - I Michael's revenge _ ) Tom Savini shocker: _ "I hate splatter!" I fRIGHT NIGHT 2 - I The FX boys _ with the bats I PHANTASM II - I See the blood spurt _ FANGORIA "77 GUTS 14 NONS ON SKATES Does Donald G. Jackson.., the man behind "The Demon Lover" and now "Roller Blade Warriors, " set out to make dumb movies on purpose? 20 "THE KISS" AND TELL "Fly" vets Chris Walas and Stephen Dupuis supply the monste,: FX for a Canadian demon tale. 26 THE BOYS OF "FRIGHT NIGHT-PART 2" FX chief Bart Mixon & his men turn beauty into beast in the vampire sequeL 30 THANKS FOR THE MAMMARIES Can "Elvira. Mistress of the Dark" make it on the big screen? Cassandra Peterson's betting her career on it. 35 PREVIEW: "NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 4" The sequel that comes as no surprise finds Freddy offing the Elm Street kids. 40 THE RETURN OF TOM SAVINI After the simian shenanigans Of "Monkey Shines, .. the Scream Great wants to segue into the director's c hair. 44 FROM. SPHERE TO SPHERE Don Coscarelli hopes he reclaimed his foothold infear fandom with "Phantasm 11. " 48 B(J(LDING A BETTER "BLOB" No more Jell-Ojokes. please. Just watch Tony Gardner's FX catapult him into makeup stardom. 52 MR. EVIL ED Thank heavens! Stephen Geolfreys, the maniacal kid from "Fright Night" and "976-EVIL, " isn't like the obnoxious twits he plays on sc reen . Publishers NORMAN .JACOBS GRAVY KERRY O' QUINN Associate Publisher 6 ELEGY Repealing 56 NIGHTMARE RITA EISENSTEIN pooper·scooper laws LIBRARY Farris jumbles Assistant Publisher 7 POSTAL ZONE MILBURfilSMITH Reader review Circulation Director roundup ART SCHULKlrt 58 PIT & PEN OF 10 MONSTER ALEX GORDON Creative Director W.R. -

À¸Œà¸¥À¸‡À¸²À¸™À¸ À¸²À¸Žà¸¢À¸™À¸•À¸£À¹œ)

Tommy Lee Wallace ภาพยนตร์ รายà¸à ¸²à¸£ (ผลงานภาพยนตร์) Dreams for Sale https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dreams-for-sale-5306721/actors It https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/it-1131225/actors Born Free: A New Adventure https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/born-free%3A-a-new-adventure-11696727/actors Fright Night Part 2 https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fright-night-part-2-1293934/actors Danger Island https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/danger-island-1471518/actors The Spree https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-spree-16681960/actors The Leprechaun-Artist https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-leprechaun-artist-16744384/actors Vampires: Los Muertos https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vampires%3A-los-muertos-1699556/actors Steel Chariots https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/steel-chariots-17461082/actors Halloween III: Season of the https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/halloween-iii%3A-season-of-the-witch-203705/actors Witch Once You Meet a Stranger https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/once-you-meet-a-stranger-2838177/actors Aloha Summer https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/aloha-summer-4190045/actors The Comrades of Summer https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-comrades-of-summer-4260113/actors And the Sea Will Tell https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/and-the-sea-will-tell-56708979/actors Little Boy Lost https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-boy-lost-6649252/actors Witness to the Execution https://th.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/witness-to-the-execution-8028409/actors. -

Proquest Dissertations

RECYCLED FEAR: THE CONTEMPORARY HORROR REMAKE AS AMERICAN CINEMA INDUSTRY STANDARD A Dissertation by JAMES FRANCIS, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: 3430304 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430304 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Approved as to style and content by: ^aJftLtfv^ *3 tu.^r TrsAAO^p P, M&^< David Lavery Martha Hixon Chair of Committee Reader Cyt^-jCc^ C. U*-<?LC<^7 Wt^vA AJ^-i Linda Badley Tom Strawman Reader Department Chair (^odfrCtau/ Dr. Michael D. Allen Dean of Graduate Studies August 2010 Major Subject: English RECYCLED FEAR: THE CONTEMPORARY HORROR REMAKE AS AMERICAN CINEMA INDUSTRY STANDARD A Dissertation by JAMES FRANCIS, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Major Subject: English DEDICATION Completing this journey would not be possible without the love and support of my family and friends. -

Book Factsheet Patricia Highsmith the Glass Cell

Book factsheet Patricia Highsmith Crime fiction, General Fiction The Glass Cell 288 pages 11.3 × 18 cm January 1976 Published by Diogenes as Die gläserne Zelle Original title: The Glass Cell Contact: Susanne Bauknecht, Rights Director, [email protected] and Bozena Huser, Film Rights, [email protected] Translation rights currently sold: English/UK (Little, Brown) English/USA (Norton) French (Calmann-Lévy) Greek (Agra) Italian (La nave di Teseo) Korean (Openhouse) Spanish/world (Anagrama) Movie adaptations 2016: A Kind Of Murder Director: Andy Goddard Screenplay: Susan Boyd Cast: Patrick Wilson, Jessica Biel, Haley Bennett 2015: Carol / Salz und sein Preis Director: Todd Haynes Screenplay: Phyllis Nagy Cast: Cate Blanchett, Rooney Mara und Kyle Chandler 2014: The two faces of January Director: Hossein Amini Screenplay: Hossein Amini Cast: Kirsten Dunst, Viggo Mortensen, Oscar Isaac 2009: Cry of the Owl Director: Jamie Thraves Screenplay: Jamie Thraves Cast: Paddy Considine, Julia Stiles 2005: Ripley under Ground Director: Roger Spottiswoode Cast: Barry Pepper, Tom Wilkinson, Claire Forlani 1999: The Talented Mr. Ripley Director: Anthony Minghella Cast: Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jude Law, Cate Blanchett 1996: Once You Meet a Stranger Director: Tommy Lee Wallace Cast: Jacqueline Bisset, Mimi Kennedy, Andi Chapman 1993: Trip nach Tunis Director: Peter Goedel Cast: Hunt David, Sillas Karen 1991: Der Geschichtenerzähler Director: Rainer Boldt Cast: Christine Kaufmann, Udo Schenk, Anke Sevenich 1 / 7 Movie adaptations (cont'd) 1989: A Curious Suicide Director: Bob Biermann Cast: Nicol Williamson, J. Lapotaire 1989: Le jardin des Disparus Director: Mai Zetterling Cast: Ian Holm, Eileen Atkins 1989: L´Amateur de Frissons Director: Roger Andrieux Cast: Jean-Pierre Bisson, Marisa Berenson 1989: L´Epouvantail Director: Maroun Bagdad Cast: Jean-Pierre Cassel, J. -

Horrorhound.Com MOVIE NEWS; 30 Days of Night, Resident Evil 3, DVD NEWS: Halloween, Etc

Winter 2007/2008 $6.95 A 25 Year BetrespectlMe BE A MONSTER! • MAKE A MONSTER! • ENLIST & UPLOAD! m MONSTERSTV.COM TO ENTER! WINTER 2007/08iiitineiR- www.horrorhound.com MOVIE NEWS; 30 Days of Night, Resident Evil 3, DVD NEWS: Halloween, etc. Featuring Grlndhouse, Tales from the Crypt, ' etc. SAN DIEGO COMIC-CON Coverage TOY NEWS: 30 Days of Night, Child's Play, Saw, Hezco Toys, etc. MUSICIANS in Horror! HALLOWEEN III Pull-Out Poster! HALLOWEEN III A HorrorHound Retrospective The History of HORROR ROCK COMIC BOOKS: Strangeland, Bump, of Army Darkness, Artist Spotlight: ON THE COVER: 30 Days of Nights makes Vampires scary again! Chucky, etc. MONTE WARD THIS ISSUE: The San Diego Comic-Con is the biggest geek- Horror’s fest of the year, and "horror geeks” luckily receive as much news and Hallowed suiprises from this annual event as anyone else: from revelations of Grounds: upcoming films to new comic announcements and video game titles. Halloween GOREHOUND; The most significant news from this year’s event is the onslaught of new action figure and collectibles due in stores over the next several Wizard of Gore months! Mezco Toys continues their line of “Cinema of Fear’ action fig- FANtasoi; ures with new additions: Leatherface from Texas Chainsaw Massacre Fan Art, Freddy 2, (based on his first film appearance) and Jason Voorhees Collector's from Frfc/ay fhe 13th Parts. On top of this. Gentle Giant has announced Spotlight Serial Killers: 2, a number of resin products from ‘Chainsaw ' 30 Days of Night and a RICHARD SPECK number of other horror comic titles! Check out page 21 for all the infor- mation concerning these announcements and many more! ROADKILL: Movie news this issue features our cover story; 30 Days of Night, HorrorHound in which we speak with Sam Raimi (producer), Josh Hartnett (star), Weekend November Steve Niles (creator) and David Slade (director): see page 8. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

I Thesis/Dissertation Sheet I Australia's -1 Global UNSW University I SYDN�Y I Surname/Family Name Dempsey Given Name/s Claire Kathleen Marsden Abbreviation for degree as give in the University calendar MPhil Faculty UNSW Canberra I School School of Humanities and Social Sciences Thesis Title 'A quick kiss in the dark from a stranger': Stephen King and the Short Story Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) There has been significant scholarly attention paid to both the short story genre and the Gothic mode, and to the influence of significant American writers, such as Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne and H.P. Lovecraft, on the evolution of these. However, relatively little consideration appears to have been offeredto the I contribution of popular writers to the development of the short story and of Gothic fiction. In the Westernworld in the twenty-firstcentury there is perhaps no contemporary popular writer of the short story in the Gothic mode I whose name is more familiar than that of Stephen King. This thesis will explore the contribution of Stephen King to the heritage of American short stories, with specific reference to the American Gothic tradition, the I impact of Poe, Hawthorneand Lovecrafton his fiction, and the significance of the numerous adaptations of his works forthe screen. I examine Stephen King's distinctive style, recurring themes, the adaptability of his work I across various media, and his status within American popular culture. Stephen King's contribution to the short story genre, I argue, is premised on his attention to the general reader and to the evolution of the genre itself, I providing as he does a conduit between contemporary an_d classic short fiction. -

The Fog Music by John Carpenter Expanded Edition Original Film Soundtrack

JOHN CARPENTER’S THE FOG MUSIC BY JOHN CARPENTER EXPANDED EDITION ORIGINAL FILM SOUNDTRACK THE 2000 REMIXED SOUNDTRACK ALBUM 1. Prologue from The Fog 2. Theme from The Fog 3. Matthew Ghost Story 4. Walk To The Lighthouse 5. Rocks At Drake’s Bay 6. The Fog 7. Antonio Bay 8. Tommy Tells Of Ghost Ships 9. Reel 9 10. Main Theme - Reprise 11. The Fog Rolls In 12. Blake In The Sanctuary 13. Finale 14. Radio Interview with Jamie Lee Curtis THE ORIGINAL 1980 SCORE CUES 1. Ghost Story 2. The Journal 3. Seagrass Attack 4. Andy on the Beach 5. Where’s The Seagrass? 6. Stevie’s Lighthouse 7. Something to Show You 8. An Evil Plan 9. Weatherman 10. Walk to Lighthouse 11. Dane 12. Morgue 13. The Fog Approaches 14. Knock at the Door 15. Fog Reflection 16. Andy’s In Trouble 17. The Fog Enters Town 18. Revenge 19. Number 6 20. The Fog End Credits STARRING ADRIENNE BARBEAU as STEVIE WAYNE JAMIE LEE CURTIS as ELIZABETH SOLLEY JANET LEIGH as KATHY WILLIAMS JOHN HOUSEMAN as MR. MACHEN TOM ATKINS as NICK CASTLE JAMES CANNING as DICK BAXTER CHARLES CYPHERS as DAN O’BANNON NANCY KYES as SANDY FADEL TY MITCHELL as ANDY WAYNE HAL HOLBROOK as FATHER MALONE DARWIN JOSTON as DR. PHIBES And JOHN CARPENTER as BENNETT Directed by JOHN CARPENTER Written by JOHN CARPENTER and DEBRA HILL Produced by DEBRA HILL Original Music by JOHN CARPENTER Cinematography by DEAN CUNDEY Film Editing by CHARLES BORNSTEIN and TOMMY LEE WALLACE Production Design by TOMMY LEE WALLACE Costume Design by STEPHEN LOOMIS and BILL WHITTENS Special Makeup Effects ROB BOTTIN In a year that would see the release of such order to plunder the ship’s stores; out of the fog’s well regarded by current evaluations. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE HORROR FANS GET A REAL TREAT WITH DOUBLE DOSE OF "HALLOWEEN" SLASHER FLICKS IN THEATRES ONE NIGHT ONLY National CineMedia's FATHOM and VOOM HD Networks' MONSTERS HD Present "Halloween 4" and "Halloween 5" With Specially-Produced Behind-the- Scenes Interviews & Footage in 250 Select Movie Theatres Nationwide Centennial, Colo. - Oct. 3, 2007 - National CineMedia's FATHOM is digging into the infamous "Halloween" vault and bringing psychotic murderer Michael Myers back to the big screen in a double- dose of horror with "Halloween 4 - The Return of Michael Myers" and "Halloween 5 - The Revenge of Michael Myers." Digitally remastered in High-Definition, the "Halloween" double feature will be presented by NCM's FATHOM and MONSTERS HD, the first-ever and only 24-hour channel exclusively devoted to horror, on October 30 th in 250 movie theatres around the country. For this one-night event, MONSTERS HD, one of the VOOM HD Networks, the largest and most diverse suite of high-definition channels nationwide, will specially-produce two featurettes - "Halloween: Faces of Fear" and "Meet the Michaels" - which will be presented in true high-definition and will air before the double feature. "Halloween: Faces of Fear" will include new and archival interviews with many members of the films' original cast and crew, including John Carpenter, the late Moustapha Akkad, Tommy Lee Wallace, Ellie Cornell and Danielle Harris, plus rare behind-the-scenes-footage shot on the Utah set of "Halloween 5." "Meet the Michaels" will feature interviews with six of the men behind the famous mask including Nick Castle (Halloween 1978); Tommy Lee Wallace (Halloween 1978); Tony Moran (Halloween 1978); George Wilbur (Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers 1988 & Halloween 6: The Curse of Michael Myers 1995); Don Shanks (Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers 1989) and Brad Loree (Halloween: Resurrection 2002). -

Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too David Roche

Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have your Cake and Eat It, Too David Roche To cite this version: David Roche. Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have your Cake and Eat It, Too. Représentations : la revue électronique du CEMRA, Centre d’Etudes sur les Modes de la Représentation Anglophone 2017. hal-01709314 HAL Id: hal-01709314 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01709314 Submitted on 14 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Représentations dans le monde Anglophone – Janvier 2017 Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have your Cake and Eat It, Too David Roche, Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès Key words: horror, remake, feminist film theory, post-feminism, politics. Mots-clés : horreur, remake, théorie féministe, post-féminisme, politiques identitaires. Remakes, as Linda Hutcheon has noted, “are invariably adaptations because of changes in context” (170), and this in spite of the fact that the medium remains the same. What Robert Stam has said of film adaptations is equally true of remakes: “they become a barometer of the ideological trends circulating during the moment of production” because they “engage the discursive energies of their time” (45). -

Whos There on Halloween? Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WHOS THERE ON HALLOWEEN? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pamela Conn et al Beall | 18 pages | 25 Aug 2003 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780843105100 | English | New York, United States Whos There on Halloween? PDF Book Retrieved May 21, Dread Central. Halloween is a widely influential film within the horror genre; it was largely responsible for the popularization of slasher films in the s and helped develop the slasher genre. Follow the little monkey through his fun-filled day with this book of poems. Upon its initial release, Halloween performed well with little advertising—relying mostly on word-of-mouth, but many critics seemed uninterested or dismissive of the film. Telotte says that this scene "clearly announces that [the film's] primary concern will be with the way in which we see ourselves and others and the consequences that often attend our usual manner of perception. Now that's sick. Retrieved September 6, This Halloween-themed collection is packed with a wide range of kids' favorite puzzles, including mazes, number puzzles, wordplay, brainteasers, matching, and our ever-popular Hidden Pictures R puzzles. The Atari Times. Philip my bag. Suspicious, Laurie goes over to the Wallace house, and finds the bodies of Annie, Bob, and Lynda, as well as Judith's headstone, in the upstairs bedroom. Add to Wishlist. Film director Bob Clark suggested in an interview released in [19] that Carpenter had asked him for his own ideas for a sequel to his film Black Christmas written by Roy Moore that featured an unseen and motiveless killer murdering students in a university sorority house. -

English Text Below

English Text below Assault on Precinct 13/Distretto 13 – Le brigate della morte (JC, 1976); AD: Tommy Lee Wallace, sceneggiatura: John Carpenter, montaggio: John Carpenter, musica: John Carpenter, fotografia (2.35:1): Douglas Knapp, durata: 91’ La figura del “cerchio ferito” scandisce una serie di grandi figurazioni della storia americana - dalla casa dei Rowlandson presa d’assalto dagli indiani nel 1676 all’attacco di Pearl Harbour, dalle fobie sulle spie comuniste alla psicosi del complotto, via via fino alla guerra del Vietnam, madre di tutte le successive formule di assedio che hanno sconvolto gli americani, non ultimo il conflitto in Iraq. Il trauma collettivo della casa/nazione assediata era rappresentanto nel cinema classico attraverso il topos dell’assedio da parte dei “pellerossa” o dei banditi. Nel cinema contemporaneo assume invece i caratteri di un incubo urbano. In Assault on Precinct 13 (forse il primo, vero ipertesto carpenteriano) i protagonisti, asserragliati in un’area circoscritta, si vedono costretti ad affrontare una minaccia venuta dell’esterno, mentre qualunque tentativo di fuga viene sistematicamente impedito. Profondamente influenzato dal magistero di Howard Hawks e dal suo Rio Bravo/Un dollaro d’onore (1959) – tanto da esserne a tratti una parafrasi – il film di Carpenter è innanzi tutto una perfetta architettura filmica, architettura dello spazio messo in scena e architettura della sceneggiatura e del découpage: l’incipit in cui vengono introdotti situazione e personaggi, la rigida scansione temporale, l’evoluzione narrativa maturata attraverso i principi del suspense, il finale in cui l’ordine viene (provvisoriamente) ristabilito. La macchina da presa diventa sguardo contemporaneamente oggettivo e soggettivo su un architettura, che deve essere scandagliata in ogni secondo alla ricerca di indizi della presenza di assalitori – questo determina sempre nuovi punti di vista tanto parziali (quelli soggettivi) che onniscienti (quelli oggettivi, dove lo spettatore sa sempre qualcosa in più rispetto ai protagonisti).