Dengue Fever in Travellers: an Increasing Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Non-Human Reservoirs of Ross River Virus: a Systematic Review of the Evidence Eloise B

Stephenson et al. Parasites & Vectors (2018) 11:188 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2733-8 REVIEW Open Access The non-human reservoirs of Ross River virus: a systematic review of the evidence Eloise B. Stephenson1*, Alison J. Peel1, Simon A. Reid2, Cassie C. Jansen3,4 and Hamish McCallum1 Abstract: Understanding the non-human reservoirs of zoonotic pathogens is critical for effective disease control, but identifying the relative contributions of the various reservoirs of multi-host pathogens is challenging. For Ross River virus (RRV), knowledge of the transmission dynamics, in particular the role of non-human species, is important. In Australia, RRV accounts for the highest number of human mosquito-borne virus infections. The long held dogma that marsupials are better reservoirs than placental mammals, which are better reservoirs than birds, deserves critical review. We present a review of 50 years of evidence on non-human reservoirs of RRV, which includes experimental infection studies, virus isolation studies and serosurveys. We find that whilst marsupials are competent reservoirs of RRV, there is potential for placental mammals and birds to contribute to transmission dynamics. However, the role of these animals as reservoirs of RRV remains unclear due to fragmented evidence and sampling bias. Future investigations of RRV reservoirs should focus on quantifying complex transmission dynamics across environments. Keywords: Amplifier, Experimental infection, Serology, Virus isolation, Host, Vector-borne disease, Arbovirus Background transmission dynamics among arboviruses has resulted in Vertebrate reservoir hosts multiple definitions for the key term “reservoir” [9]. Given Globally, most pathogens of medical and veterinary im- the diversity of virus-vector-vertebrate host interactions, portance can infect multiple host species [1]. -

This Report Considers the Development of a National Pest Manag

Exclusion and Control of Exotic Mosquitoes of Public Health Significance .............................................................................................................. Report to the Minister for Biosecurity Published by Public Health Group, Ministry of Health, Manatü Hauora Wellington, New Zealand June 1997 (Revised September 1997) ISBN 0-478-20853-7 (Booklet) ISBN 0-478 20854-5 (Internet) Summary of Key Issues Potentially the most significant mosquito-borne diseases to New Zealand are the arboviral diseases Ross River Fever (Epidemic Polyarthritis), Dengue Fever, Barmah Forest virus and Japanese Encephalitis. The establishment and maintenance of a nationally co-ordinated approach to exclude and control exotic mosquitoes of public health significance is crucial to protect the public health. There are number of species of mosquitoes that should be of concern to New Zealand. The species of greatest concern is Aedes albopictus, the Asian Tiger Mosquito, a competent vector for Ross River Virus and Dengue. The risk of an outbreak of an arboviral disease or malaria in New Zealand is real and is likely to increase with time. In terms of potential entry of exotic mosquitoes, North Island port cities, such as those in Auckland and Northland, are more important than cities without either major international airports or shipping. The likely consequences of a major outbreak of arboviral disease are so serious that all reasonable steps should be taken to prevent such an occurrence. Enhancements are required to existing border control, -

Ecology and Geography of Human Monkeypox Case Occurrences Across Africa

Ecology and Geography of Human Monkeypox Case Occurrences Across Africa Christine Ellis DVM Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine Manhattan, KS . Monkeypox Ecological Niche Modeling My Project . Introduction to Monkeypox Monkeypox – Virus Orthopoxvirus, Poxviridae, Chordopoxvirinae cowpox, vaccinia, variola Central genome tightly conserved Key functions: transcription, virus assembly Genes at termini are more variable Associated with virus-host interactions www.ci.vbi.vt.edu/pathinfo/pathogens/Monkeypox_virus_Info.shtml Monkeypox – Virus 2 geographically distinct clades Congo Basin clade West African clade 99% identical Diversity is located in the terminal regions West African clade Less virulent Less transmissible www.rst.gsfc.nasa.gov/Sect6/Sect6 Monkeypox – Human Disease “Emerged” in 1970-1971 After successful eradication of smallpox West and Central Africa rural, tropical rainforest areas Number of Reported* Cases of Monkeypox 500 400 300 # cases 200 100 Number of cases 0 1970- 1980- 1987- 1993- 1996 1997 1979 1986 1992 1995 Year Monkeypox – Human Disease 2003: United States 72 cases: 37 confirmed Monkeypox – Human Disease Source of virus Source of human infection www.nps.gov photos.igougo.com www.pets-classifieds.co.uk www.everwonder.com/david/bullwinkle Monkeypox – Clinical Presentation 10-14 day incubation 1-3 day prodrome Fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy, URT illness 2-4 weeks: febrile rash illness: Begins on the trunk, spreads centrifugally Macular, papular, vesicular, pustular stages -

Zoonotic Potential of International Trade in CITES-Listed Species Annexes B, C and D JNCC Report No

Zoonotic potential of international trade in CITES-listed species Annexes B, C and D JNCC Report No. 678 Zoonotic potential of international trade in CITES-listed species Annex B: Taxonomic orders and associated zoonotic diseases Annex C: CITES-listed species and directly associated zoonotic diseases Annex D: Full trade summaries by taxonomic family UNEP-WCMC & JNCC May 2021 © JNCC, Peterborough 2021 Zoonotic potential of international trade in CITES-listed species Prepared for JNCC Published May 2021 Copyright JNCC, Peterborough 2021 Citation UNEP-WCMC and JNCC, 2021. Zoonotic potential of international trade in CITES- listed species. JNCC Report No. 678, JNCC, Peterborough, ISSN 0963-8091. Contributing authors Stafford, C., Pavitt, A., Vitale, J., Blömer, N., McLardy, C., Phillips, K., Scholz, L., Littlewood, A.H.L, Fleming, L.V. & Malsch, K. Acknowledgements We are grateful for the constructive comments and input from Jules McAlpine (JNCC), Becky Austin (JNCC), Neville Ash (UNEP-WCMC) and Doreen Robinson (UNEP). We also thank colleagues from OIE for their expert input and review in relation to the zoonotic disease dataset. Cover Photographs Adobe Stock images ISSN 0963-8091 JNCC Report No. 678: Zoonotic potential of international trade in CITES-listed species Annex B: Taxonomic orders and associated zoonotic diseases Annex B: Taxonomic orders and associated zoonotic diseases Table B1: Taxonomic orders1 associated with at least one zoonotic disease according to the source papers, ranked by number of associated zoonotic diseases identified. -

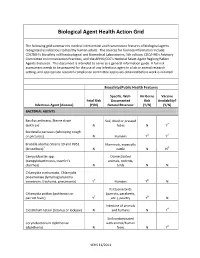

Biological Agent Health Action Grid

Biological Agent Health Action Grid The following grid summarizes medical intervention and transmission features of biological agents recognized as infectious to healthy human adults. The sources for foonote information include: CDC/NIH’s Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, 5th edition; CDC/HHS’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; and the APHIS/CDC’s National Select Agent Registry/Select Agents Exclusion. This document is intended to serve as a general information guide. A full risk assessment needs to be prepared for the use of any infectious agent in a lab or animal research setting, and appropriate research compliance committee approvals obtained before work is initiated. Biosafety/Public Health Features Specific, Well- Air-Borne Vaccine Fetal Risk Documented Risk Availability? Infectious Agent (disease) (Y/N) Natural Reservoir (Y/N) (Y/N) BACTERIAL AGENTS Bacillus anthracis, Sterne strain Soil, dried or pressed (anthrax)1 N hides N Y2 Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough or pertussis) N Humans Y3 Y4 Brucella abortus Strains 19 and RB51 Mammals, especially (brucellosis)5 N cattle N N6 Campylobacter spp. Domesticated (campylobacteriosis, traveler's animals, rodents, diarrhea) N birds N N Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae (lymphogranuloma venereum, trachoma, pneumonia) Y7 Humans Y8 N Psittacine birds Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis or (parrots, parakeets, parrott fever) Y7 etc.), poultry Y8 N Intestine of animals Clostridium tetani (tetanus or lockjaw) N and humans N Y4 Soil contaminated Corynebacterium diphtheriae with animal/human (diphtheria) N feces N Y4 VEHS 11/2011 Specific, Well- Air-Borne Vaccine Fetal Risk Documented Risk Availability? Infectious Agent (disease) (Y/N) Natural Reservoir (Y/N) (Y/N) Francisella tularensis, subspecies Wild animals, esp. -

Position Paper: Rural Health Policy in a Changing Climate – Three Key Issues

Position paper: Rural health policy in a changing climate – three key issues 28 January 2021 … healthy and sustainable rural, regional and remote communities Postal Address: PO Box 280 Deakin West ACT 2600 Address: 10 Campion St Deakin ACT 2600 Phone: 02 6285 4660 Fax: 02 6285 4670 Email: [email protected] Page 2 National Rural Health Alliance Position paper: Rural health policy in a changing climate – three key issues Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Climate change ................................................................................................................. 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 3 The three key issues.......................................................................................................... 4 Extreme weather events ............................................................................................... 4 Australian climate observations .................................................................................................... 4 Temperature ............................................................................................................................ 4 Rainfall ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Cyclones .................................................................................................................................. -

NSW Vector-Borne Diseases Annual Report

Vector-Borne Diseases Arbovirus and other vector-borne disease surveillance in NSW NSW ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Produced by: COMMUNICABLE DISEASES BRANCH Health Protection NSW Locked Mail Bag 961 North Sydney NSW 2059 Email: [email protected] www.health.nsw.gov.au/infectious/pages/default.aspx This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study and training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. It may not be reproduced for commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires written permission from Health Protection NSW. Suggested citation: Communicable Diseases Branch. NSW Vector-Borne Diseases Annual Surveillance Report: 2018. Sydney: Health Protection NSW, 2019. © Health Protection NSW 2019 June, 2019 SHPN (HP NSW) 190144 2 | Page TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and abbreviations ........................................................................................................................... 4 Summary – Vector-borne diseases in NSW .................................................................................................... 5 Key trends in 2017 ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Mosquito and sentinel chicken surveillance for vector-borne arboviruses .................................................... 5 Barmah Forest virus ...................................................................................................................................... -

Addendum to Our Submission of 7 Dec: Terms of Reference

Addendum to our submission of 7th Dec: Terms of Reference I would like to address the following Terms of Reference of the Committee: • Strategic approach to managing the species at a regional level. The public health issues outlined hereunder suggest that both Federal and State authorities need to co-ordinate a strategic national approach to species management as a matter of priority. Risks to Public health and Agriculture: We currently have flying-fox roosts in some 56 regional centres and city suburbs spread over 3,000km of the East coast, that have given their local council cause to get permits to carry out management activity. Some of these roosts are seasonal, some permanent. We tolerate the existence of these bio-concentrations on the basis that flying-fox populations are ‘critical’ to the health of our rain forests and native bush. They may very well be important, perhaps critical, but in either case it is evident that the health and survival of the species and benefit to our bush, is NOT dependent on camps or roosts being located and tolerated in residential or suburban areas. As a community we would quite reasonably prohibit the establishment of a poultry farm with say 20,000 birds in the middle of a regional CBD or a Sydney suburb, citing noise, smell, disease risk etc. However recently a bio-concentration of around 300,000 animals was allowed to build up in a small regional town, Batemans Bay, before effective dispersal action was taken. These animals are known disease carriers and in recent years have caused human fatalities in Australia from both ABLV (Australian Bat Lyssavirus) and Hendra. -

Mosquito-Borne Diseases: Social Representations of Auniversity Community in Endemic Outbreaks

Brief Report Mosquito-Borne Diseases: Social Representations of aUniversity Community in Endemic Outbreaks Sylvain Delouvée 1,*, Gail Moloney 2, Kathleen McColl 3 and Grégory Lo Monaco 4 1 Department of Psychology, Université Rennes 2, LP3C–EA 1285, 35000 Rennes, France 2 School of Health and Human Sciences, Southern Cross University, Military Rd, East Lismore, NSW 1235, Australia; [email protected] 3 School of Public Health–École des Hautes Études en Santé Publique, 35000 Rennes, France; [email protected] 4 Department of Social Psychology, Aix Marseille Université, ADEF–EA 4671, 13013 Marseille, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-(0)2-99-14-19-47 Abstract: (1) Background: Studying social representations as lay theories allows for a better under- standing of the common sense knowledge constructed around mosquito-borne diseases and the impact this may have on attitudes and behaviors. (2) Methods: A hierarchical evocation questionnaire was circulated through an Australian academic community and analyzed by prototypical analysis and correspondence factor analysis. (3) Results: Representational areas are regulated by participant age and whether or not they had contracted a mosquito-borne disease. (4) Conclusions: Collecting and understanding social representations has the potential to help social actors implement strategies that encourage people to access information and adopt behaviors in line with the scientific reality of the phenomenon, rather than limiting lay theories. Citation: Delouvée, S.; Moloney, G.; Keywords: social representations; emerging infectious diseases; mosquito-borne diseases; health- McColl, K.; Lo Monaco, G. protective behaviors Mosquito-Borne Diseases: Social Representations of a University Community in Endemic Outbreaks. -

Chikungunya Fever Disease Chikungunya Fever Is

Chikungunya fever disease Chikungunya fever is an arboviral disease caused by an alphavirus(CHIKV) belonging to the order unassigned, togaviridae family, genus alphavirus, and transmitted to humans mainly by infected mosquitoes of the Aedes alphavirus genus (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus). Figure 1 shows the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) Figure 1 They also transmit dengue fever types 1 to 4, and zika virus. Chikungunya virus is transmitted to people through infected female mosquitoes bites of the Aedes species. The virus is mainly “spread from person to person through mosquitoes. Mosquitoes become infected when they feed on a person already infected with the virus. Infected mosquitoes can then spread the virus to other people through bites. Chikungunya virus is most often spread to people by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. These are the same mosquitoes that transmit dengue virus. They bite mostly during the daytime. Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) was first isolated from human serum during a febrile illness outbreak in Tanzania in 1953. The word chikungunya is derived from Makonde (Kimakonde), one of the languages spoken in southeastern Tanzania, and means “to bend over or become contorted”, referring to the posture adopted by the patient due to serious joint pain in severe infections caused by CHIKV. Figures 2 and 3 show the Aedes aegypti Figure 3 Viral disease is transmitted by the bite of infected female mosquitoes of the Aedes species Rarely, the transmission is from mother to child. Chikungunya virus is transmitted rarely from mother to newborn around the time of birth. To date, no infants have been found to be infected with chikungunya virus through breastfeeding. -

Ross River Virus Symptoms: Fifty-Year-Old Medicine Could Have Potential to Ease Suffering

Ross River virus symptoms: Fifty-year-old medicine could have potential to ease suffering Janelle Miles, The Courier-Mail September 7, 2016 12:00am Subscriber only GRIFFITH University researchers have found a new use for a 50-year-old medicine as a potential therapy for the debilitating Ross River virus. Human trials to test the effectiveness of an injectable form of pentosan polysulfate in Ross River fever patients are expected to begin in Queensland early next year. But scientist Lara Herrero, of the university’s Institute for Glycomics, on the Gold Coast, said five patients diagnosed with the mosquito-borne virus had already been given the drug through a special access scheme with “good success”. She said comprehensive testing in animals infected with Ross River fever, or the closely related chikungunya virus, had also found “massive improvements” in joint pain and swelling after treatment with pentosan polysulfate. Dr Lara Herrero, a researcher at Griffith University. Picture: Tim Marsden The viruses can cause crippling pain and joint arthritis so severe the symptoms can last years. “This drug protects cartilage in the joints, to prevent them from being broken down, and, in doing so, reduces pain,” Dr Herrero said. “It also reduces the proteins that cause inflammation.” Pentosan polysulfate is already registered in Australia as an oral treatment for cystitis, which is inflammation of the bladder. Dr Herrero started work on finding a treatment for Ross River fever after contracting it herself as a PhD student in Perth more than a decade ago. “I was acutely ill for about three to four months,” she said. -

Arboviral Infections—TRAVELER INFORMATION • Introduction • Transmission • Symptoms • Disease Information • Prevention Strategies • Need for Medical Assistance

Traveler Information QUICK LINKS Arboviral Infections—TRAVELER INFORMATION • Introduction • Transmission • Symptoms • Disease Information • Prevention Strategies • Need for Medical Assistance Traveler Information ARBOVIRAL INFECTIONS This article includes Rift Valley fever, Ross River fever, and Equine Encephalitis. See also the articles: Chikungunya, Yellow Fever, Dengue , Japanese encephalitis, Tick-borne Encephalitis, West Nile Virus, and Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. INTRODUCTION Arboviral infections are transmitted by mosquitoes, sandflies, and ticks. Most human infections are mild but some can cause serious disease. Many of these infections cause small, localized epidemics that occasionally involve travelers; others may be transported accidentally from one geographical area to another, such as the West Nile virus that was introduced into the eastern seaboard of the United States. Immunity after human infection is usually life-long, though infection by one dengue serotype may increase sensitivity and the risk of complications to infection with another serotype. TRANSMISSION Arboviruses live in birds, rodents, and monkeys, as well as the mosquitoes, sandflies, and ticks that transmit the infection. Humans are incidental hosts. Outbreaks of human infections are often local and seasonal and are affected by climate change such as the El Nino effect. The risk of infection to travelers is therefore extremely difficult to predict. Risk to travelers is normally low, patchy, and seasonal; the risk of serious complications is slight. The clinical incubation period is usually less than 1 week. SYMPTOMS Features common to most arboviral infections include fever, redness of the conjunctiva, pain in the orbit of the eye, muscle and joint pain, photophobia, rash, and enlarged lymph glands. Jaundice, confusion, convulsions, and shock may occur.