Myanmar's Security Outlook and the Myanmar Defence Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2003/297/CFSP of 28 April 2003 on Burma/Myanmar

L 106/36EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2003 (Acts adopted pursuant to Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2003/297/CFSP of 28 April 2003 on Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, will not be imposed if by that time there is substantive progress towards national reconciliation, the restoration of a democratic order and greater respect for human Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in parti- rights in Burma/Myanmar. cular Article 15 thereof, (6) Exemptions should be introduced in the arms embargo Whereas: in order to allow the export of certain military rated equipment for humanitarian use. (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council adopted Common Position 96/635/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar (1), which (7) The implementation of the visa ban should be without expires on 29 April 2003. prejudice to cases where a Member State is bound by an obligation of international law, or is host country of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (2) In view of the further deterioration in the political situa- (OSCE), or where the Minister and Vice-Minister for tion in Burma/Myanmar, as witnessed by the failure of Foreign Affairs for Burma/Myanmar visit with prior noti- the military authorities to enter into substantive discus- fication and agreement of the Council. sions with the democratic movement concerning a process leading to national reconciliation, respect for human rights and democracy and the continuing serious (8) The implementation of the ban on high level visits at the violations -

China, India, and Myanmar: Playing Rohingya Roulette?

CHAPTER 4 China, India, and Myanmar: Playing Rohingya Roulette? Hossain Ahmed Taufiq INTRODUCTION It is no secret that both China and India compete for superpower standing in the Asian continent and beyond. Both consider South Asia and Southeast Asia as their power-play pivots. Myanmar, which lies between these two Asian giants, displays the same strategic importance for China and India, geopolitically and geoeconomically. Interestingly, however, both countries can be found on the same page when it comes to the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. As the Myanmar army (the Tatmadaw) crackdown pushed more than 600,000 Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi’s government was vociferously denounced by the Western and Islamic countries.1 By contrast, China and India strongly sup- ported her beleaguered military-backed government, even as Bangladesh, a country both invest in heavily, particularly on a competitive basis, has sought each to soften Myanmar’s Rohingya crackdown and ease a medi- ated refugee solution. H. A. Taufiq (*) Global Studies & Governance Program, Independent University of Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2019 81 I. Hussain (ed.), South Asia in Global Power Rivalry, Global Political Transitions, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7240-7_4 82 H. A. TAUFIQ China’s and India’s support for Myanmar is nothing new. Since the Myanmar military seized power in September 1988, both the Asian pow- ers endeavoured to expand their influence in the reconfigured Myanmar to protect their national interests, including heavy investments in Myanmar, particularly in the Rakhine state. -

Regional Reverberations from Regime Shake-Up in Rangoon.Qxd

Asia-PacificAsia-Pacific SecuritySecurity SStudiestudies RegionalRegional ReverberationsReverberations fromfrom RegimeRegime Shake-upShake-up inin RangoonRangoon Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Volume 4 - Number 1, January 2005 Key Findings The reverberations from the recent regime shake-up in Rangoon continue to be felt in regional capitals. Since prime minister Khin Nyunt was the chief architect of closer China-Burma strategic ties, his sudden removal has been interpret- ed as a major setback for China's strategic goals in Burma. Dr. Mohan Malik is a Professor with the Asia-Pacific Center for However, an objective assessment of China's strategic and eco- Security Studies. nomic needs and Burma's predicament shows that Beijing is His work focuses main- unlikely to easily give up what it has already gained in and ly on Asian Geopolitics through Burma. From China's perspective, Burma should be and Proliferation in Asia-Pacific region. His satisfied to gain a powerful friend, a permanent member of the most recent APCSS UN Security Council, and an economic superpower that comes publication is “India-China Relations: bearing gifts of much needed military hardware, economic aid, Giants Stir, Cooperate infrastructure projects and diplomatic support. and Compete ” The fact remains that ASEAN, India and Japan cannot compete with China either in providing military assistance, diplomatic support or in offering trade and investment benefits. With the UN-brokered talks on political reconciliation having reached a dead end, it might be worthwhile to start afresh with a dia- logue framework of ASEAN+3 (ASEAN plus China, India and Japan) on Burma. This would also put to test China's oft-stated commitment to multi- lateralism and Beijing's penchant for "Asian solutions to Asian problems". -

Political Monitor No.6

Euro-Burma Office 1 to 11 February 2011 Political Monitor POLITICAL MONITOR NO. 6 THAN SHWE TO HEAD EXTRA-CONSTITUTIONAL “STATE SUPREME COUNCIL” Although the SPDC regime had indicated that it would hand over state power to President Thein Sein and his government, junta chief Senior-General Than Shwe has now revealed that he will personally lead a newly created council called the “State Supreme Council”, which, as its name implies, will be the most powerful body in the country, according to sources in Nay Pyi Taw. Two bodies have now emerged in the new government's administrative structure that observers say will have powers that reach—either directly or indirectly—above and beyond the powers of the new civilian executive and legislative branches. The first is the 8 member State Supreme Council, not mentioned in the 2008 Constitution. The second is the 11 member National Defence and Security Council (NDSC), which is in the 2008 Constitution and will be led by Thein Sein. “The State Supreme Council will become the highest body of the state. While it will assume an advisory role to guide the future governments, the body will be very influential,” says a source close to the military. The members of the State Supreme Council will include: 1 Sr-Gen Than Shwe former SPDC Chair (78) 2 V-Sr-Gen Maung Aye former SPDC Vice-Chair (74) Speaker, Pyithu 3 Thura Shwe Mann former SPDC member, General (64) Hluttaw 4 Thein Sein former SPDC Lt-Gen (66) President 5 Thiha Thura Tin Aung Myint Oo former General (61) Vice-President 6 Tin Aye former SPDC Member, Lt-Gen Ordinance A yet unidentified senior military 7 general A yet unidentified senior military 8 general As required by the 2008 Constitution, the NDSC will be made up of: 1. -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

Official Journal of the European Communities 24.5.2000

24.5.2000 EN Official Journal of the European Communities L 122/1 (Acts adopted pursuant to Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION of 26 April 2000 extending and amending Common Position 96/635/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar (2000/346/CFSP) THE COUNCIL OFTHE EUROPEAN UNION, whose names are listed in the Annex and their families. Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in par- ticular Article 15 thereof, By agreement of all Member States, the ban on the issue of an entry visa for the Foreign Minister may Whereas: be waived where it is in the interests of the Euro- (1) Common Position 96/635/CFSP of 28 October 1996 on pean Union; Burma/Myanmar (1) expires on 29 April 2000. (ii) high-level bilateral government (Ministers and offi- cials of political director level and above) visits to (2) There are severe and systematic violations of human Burma/Myanmar will be suspended; rights in Burma, with continuing and intensified repres- (iii) funds held abroad by persons referred to in (i) will sion of civil and political rights, and the Burmese be frozen; authorities have taken no steps towards democracy and national reconciliation. (iv) no equipment which might be used for internal repression or terrorism will be supplied to Burma/ (3) In this connection, the restrictive measures taken under Myanmar.’ Common Position 96/635/CFSP should be extended and strengthened. Article 2 (4) Action by the Community is needed in order to imple- Common Position 96/635/CFSP is hereby extended until 29 ment some of the measures cited below, October 2000. -

Commission Regulation (EC)

L 108/20 EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2009 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Common Position 2009/351/CFSP of 27 April 2009 ( 2 ) amends Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. Annexes VI and VII Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 should, therefore, be Community, amended accordingly. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 of (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regu- force immediately, lation (EC) No 817/2006 ( 1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b) thereof, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Whereas: Article 1 1. Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the replaced by the text of Annex I to this Regulation. persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. 2. Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby replaced by the text of Annex II to this Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enter- prises owned or controlled by the Government of Article 2 Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publi- that Regulation. -

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook:Tatmadaw in a New

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook: Tatmadaw in a New Political Environment Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction In March 2016, the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF), or Myanmar Defence Services (MDS) which goes by the name “Tatmadaw (Royal Force),” supported the smooth transfer of power from President Thein Sein (whose Union Solidarity and Development Party lost the election) to President Htin Kyaw (nominated by the National League for Democracy that won the election).1 Despite speculations that the winning party and the Tatmadaw would lock horns as the former challenges the constitutionally-guaranteed political role of the military, the two protagonists seemed to have arrived at a modus vivendi that allowed for peaceful coexistence throughout the year. On the other hand, the last quarter of 2016 saw two seriously difficult security challenges that took the MDS by surprise both in terms of ferocity and suddenness. The consequences of the two violent attacks initiated by Muslim insurgents in the western Rakhine State, and an alliance of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the northern Shan State, have gone beyond purely military challenges in view of their sheer complexity involving complicated issues of identity, ethnicity, and historical baggage as well as socio-economic and political grievances. Occurring at the border fo Bangladesh, the Rakhine conflagration, with religious and racial undertones, invited unwanted attention from Muslim countries while the fighting in the north bordering China raised concerns over potential Chinese reaction to serve its national interest. As such, Tatmadaw’s massive response to these challenges came under great scrutiny from the international community in general and human rights advocacy groups in particular. -

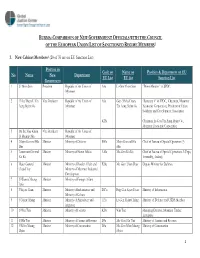

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Interpreting Myanmar a Decade of Analysis

INTERPRETING MYANMAR A DECADE OF ANALYSIS INTERPRETING MYANMAR A DECADE OF ANALYSIS ANDREW SELTH Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464042 ISBN (online): 9781760464059 WorldCat (print): 1224563457 WorldCat (online): 1224563308 DOI: 10.22459/IM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Yangon, Myanmar by mathes on Bigstock. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Acronyms and abbreviations . xi Glossary . xv Acknowledgements . xvii About the author . xix Protocols and politics . xxi Introduction . 1 THE INTERPRETER POSTS, 2008–2019 2008 1 . Burma: The limits of international action (12:48 AEDT, 7 April 2008) . 13 2 . A storm of protest over Burma (14:47 AEDT, 9 May 2008) . 17 3 . Burma’s continuing fear of invasion (11:09 AEDT, 28 May 2008) . 21 4 . Burma’s armed forces: How loyal? (11:08 AEDT, 6 June 2008) . 25 5 . The Rambo approach to Burma (10:37 AEDT, 20 June 2008) . 29 6 . Burma and the Bush White House (10:11 AEDT, 26 August 2008) . 33 7 . Burma’s opposition movement: A house divided (07:43 AEDT, 25 November 2008) . 37 2009 8 . Is there a Burma–North Korea–Iran nuclear conspiracy? (07:26 AEDT, 25 February 2009) . 43 9 . US–Burma: Where to from here? (14:09 AEDT, 28 April 2009) . -

Actos Adoptados En Aplicación Del Título V Del Tratado De La Unión Europea

L 154/116ES Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea 21.6.2003 (Actos adoptados en aplicación del título V del Tratado de la Unión Europea) DECISIÓN 2003/461/PESC DEL CONSEJO de 20 de junio de 2003 por la que se aplica la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC sobre Birmania/Myanmar EL CONSEJO DE LA UNIÓN EUROPEA, DECIDE: Vista la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC, de 28 de abril de 2003, sobre Birmania/Myanmar (1), y en particular sus artículos Artículo 1 8 y 9, junto con el apartado 2 del artículo 23 del Tratado de la La lista de personas que figura en el anexo de la Posición Unión Europea, Común 2003/297/PESC se sustituye por la lista que figura en el anexo. Considerando lo siguiente: (1) De acuerdo con el artículo 9 de la Posición Común Artículo 2 2003/297/PESC, la ampliación de determinadas sanciones allí establecidas, así como las prohibiciones Queda levantada la suspensión de las disposiciones del apartado establecidas en el apartado 2 del artículo 2 de la misma 2 del artículo 2 de la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC tal y Posición Común se suspendieron hasta el 29 de octubre como se establece en la letra b) del artículo 9 de la Posición de 2003, salvo que el Consejo decida lo contrario. Común. (2) A la vista del persistente deterioro de la situación política Artículo 3 en Birmania, en particular el arresto de Aung San Suu Kyi y otros destacados miembros de la Liga Nacional La presente Decisión surtirá efecto a partir del día de su adop- para la Democracia y el cierre de las oficinas de la ción. -

Myanmar Security Outlook: Peace-Making, Ceasefires, Communal Tensions and Politics

CHAPTER 4 Myanmar Security Outlook: Peace-making, Ceasefires, Communal Tensions and Politics Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction In accordance with the 2008 Constitution, President Thein Sein’s Union Government comprises two elected vice presidents and an appointed cabinet of Union ministers as well as the Attorney General. The bicameral legislature constitutes the Amyotha Hluttaw (national assembly or upper house) and Pyithu Hluttaw (people’s assembly or lower house) each of which includes 25 per cent military representatives nominated by the Commander-in-Chief (who has the status of Vice President but ranked 7th in national protocol). Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (union assembly) functions as the combined forum of both houses of Parliament. The executive and legislative branches together with the judiciary underpin the political regime instituted through the 2008 Constitution. Formulated under the auspices of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) it was described as “discipline flourishing democracy” by its designers. Administratively, Myanmar has 14 provinces comprising seven states (named after the major non-Bamar ethnic group that inhabits the region) and seven regions (areas with Bamar ethnic group as majority) each with its own government (headed by a chief minister, a Presidential appointee) and legislative assembly (Parliament). Some provinces include quasi-autonomous territories each designated as a self- administered division or zone (depending upon population) for ethnic minority communities. Below the provincial level, in a descending order of administrative authority, are districts, townships, and wards (in town) as well as village tracts (grouping of villages in the countryside). The national capital called Nay Pyi Taw (meaning abode of kings) was established in November 2005, replacing Yangon and administered separately as Union territory.