The Discovery of the Penicillin.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fleming Vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold Kristin Hess La Salle University

The Histories Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 3 Fleming vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold Kristin Hess La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hess, Kristin () "Fleming vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold," The Histories: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/the_histories/vol2/iss1/3 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH stories by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Histories, Vol 2, No. 1 Page 3 Fleming vs. Florey: It All Comes Down to the Mold Kristen Hess Without penicillin, the world as it is known today would not exist. Simple infections, earaches, menial operations, and diseases, like syphilis and pneumonia, would possibly all end fatally, shortening the life expectancy of the population, affecting everything from family-size and marriage to retirement plans and insurance policies. So how did this “wonder drug” come into existence and who is behind the development of penicillin? The majority of the population has heard the “Eureka!” story of Alexander Fleming and his famous petri dish with the unusual mold growth, Penicillium notatum. Very few realize that there are not only different variations of the Fleming discovery but that there are also other people who were vitally important to the development of penicillin as an effective drug. -

Microorganisms: Friend and Foe : MCQ for VIII: Biology 1.The Yeast

Microorganisms: Friend and Foe : MCQ for VIII: Biology 1.The yeast multiply by a process called (a) Binary fission (b) Budding (c) Spore formation (d) None of the above 2.The example of protozoan is (a) Penicillium (b) Blue green algae (c) Amoeba (d) Bacillus 3.The most common carrier of communicable diseases is (a) Ant (b) Housefly (c) Dragonfly (d) Spider 4.The following is an antibiotics (a) Alcohol (b) Yeast (c) Sodium bicarbonate (d) Streptomycin 5.Yeast produces alcohol and carbon dioxide by a process called (a) Evaporation (b) Respiration (c) Fermentation (d) Digestion 6.The algae commonly used as fertilizers are called (a) Staphylococcus (b) Diatoms (c) Blue green algae (d) None of the above 7.Cholera is caused by (a) Bacteria (b) Virus (c) Protozoa (d) Fungi 8.Plant disease citrus canker is caused by (a) Virus (b) Fungi (c) Bacteria (d) None of these 9.The bread dough rises because of (a) Kneading (b) Heat (c) Grinding (d) Growth of yeast cells 10.Carrier of dengue virus is (a) House fly (b) Dragon fly (c) Female Aedes Mosquito (d) Butterfly 11. Yeast is used in the production of (a) Sugar (b) Alcohol (c) Hydrochloric acid (d) Oxygen 12. The vaccine for smallpox was discovered by (a) Robert Koch (b) Alexander Fleming (c) Sir Ronald Ross (d) Edward Jenner 13.Chickenpox is caused by (a) Virus (b) Fungi (c) Protozoa (d) Bacteria 14.The bacterium which promote the formation of curd (a) Rhizobium (b) Spirogyra (c) Breadmould (d) Lactobacillus 15.Plasmodium is a human parasite which causes (a) dysentery (b) Sleeping sickness (c) Malaria -

Heroes and Heroines of Drug Discovery

Heroes and Heroines of Drug Discovery Talking Science Lecture The Rockefeller University January 9, 2016 Mary Jeanne Kreek Mary Jeanne Kreek (b. February 9, 1937) • Recruited by a Rockefeller University researcher, Vincent P. Dole, to assess addiction, with the focus of seeing addiction as an illness, not a choice • Research focused on the synthetic drug methadone, which she found relieved heroin cravings and prevented withdrawal symptoms • Helped get methadone approved as a long term opiate addiction therapy in 1973 • Transformed our understanding of addiction from a personal shortcoming to a medical disease Alexander Fleming Alexander Fleming (August 6, 1881 – March 11, 1955) • 1928 – observed that mold accidentally developed on a staphylococcus culture plate which had created a bacteria-free circle around itself • Further experimentation found that this mold, even when diluted 800 times, prevented the growth of staphylococci • He would name it Penicillin • 1945 – won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Charles L. Sawyers Charles L. Sawyers (b. 1959) • Interested in the Philadelphia Chromosome, a genetic aberration where 2 chromosomes swap segments, enabling white blood cells to grow without restraint and causing chronic myeloid leukemia • Focused on determining what turns cancer cells “on” or “off” • Found the specific oncogenes that control a cancer cell and shut them off – Enabled patients to receive a treatment targeted specifically for their cancer, rather than a general treatment for all kinds of cancer • 2013 – won the Breakthrough -

Alexander Fleming and the Discovery of Penicillin

The miraculous mold… Fleming’s Life Saving Discovery lexander Fleming is His famous discovery happened credited with the on the day that Fleming Adiscovery of penicillin; perhaps returned to his laboratory the greatest achievement in having spent August on holiday medicine in the 20th Century. with his family. Before leaving, By Jay Hardy, CLS, SM (NRCM) he had stacked all his cultures Having grown up in Scotland, of staphylococci on a bench in a Fleming moved to London corner of his laboratory. On Jay Hardy is the founder and where he attended medical returning, Fleming noticed that president of Hardy Diagnostics. school. After serving his one culture was contaminated He began his career in country as a medic in World with a fungus, and that the microbiology as a Medical Technologist in Santa Barbara, War I, he returned to London colonies of staphylococci that California. where he began his career as a had immediately surrounded it In 1980, he began manufacturing bacteriologist. There he began had been destroyed, whereas culture media for the local his search for more effective other colonies farther away hospitals. Today, Hardy antimicrobial agents. Having were normal. Diagnostics is the third largest culture media manufacturer in the witnessed the death of many United States. wounded soldiers in the war, he noticed that in many cases the To ensure rapid and reliable turn around time, Hardy Diagnostics use of harsh antiseptics did maintains seven distribution more harm than good. centers, and produces over 3,500 products used in clinical and industrial microbiology By 1928, Fleming was laboratories throughout the world. -

The British Army's Contribution to Tropical Medicine

ORIGINALREVIEW RESEARCH ClinicalClinical Medicine Medicine 2018 2017 Vol Vol 18, 17, No No 5: 6: 380–3 380–8 T h e B r i t i s h A r m y ’ s c o n t r i b u t i o n t o t r o p i c a l m e d i c i n e Authors: J o n a t h a n B l a i r T h o m a s H e r r o nA a n d J a m e s A l e x a n d e r T h o m a s D u n b a r B general to the forces), was the British Army’s first major contributor Infectious disease has burdened European armies since the 3 Crusades. Beginning in the 18th century, therefore, the British to tropical medicine. He lived in the 18th century when many Army has instituted novel methods for the diagnosis, prevention more soldiers died from infections than were killed in battle. Pringle and treatment of tropical diseases. Many of the diseases that observed the poor living conditions of the army and documented are humanity’s biggest killers were characterised by medical the resultant disease, particularly dysentery (then known as bloody ABSTRACT officers and the acceptance of germ theory heralded a golden flux). Sanitation was non-existent and soldiers defecated outside era of discovery and development. Luminaries of tropical their own tents. Pringle linked hygiene and dysentery, thereby medicine including Bruce, Wright, Leishman and Ross firmly contradicting the accepted ‘four humours’ theory of the day. -

Nobel Laureate Surgeons

Literature Review World Journal of Surgery and Surgical Research Published: 12 Mar, 2020 Nobel Laureate Surgeons Jayant Radhakrishnan1* and Mohammad Ezzi1,2 1Department of Surgery and Urology, University of Illinois, USA 2Department of Surgery, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia Abstract This is a brief account of the notable contributions and some foibles of surgeons who have won the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine since it was first awarded in 1901. Keywords: Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine; Surgical Nobel laureates; Pathology and surgery Introduction The Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine has been awarded to 219 scientists in the last 119 years. Eleven members of this illustrious group are surgeons although their awards have not always been for surgical innovations. Names of these surgeons with the year of the award and why they received it are listed below: Emil Theodor Kocher - 1909: Thyroid physiology, pathology and surgery. Alvar Gullstrand - 1911: Path of refracted light through the ocular lens. Alexis Carrel - 1912: Methods for suturing blood vessels and transplantation. Robert Barany - 1914: Function of the vestibular apparatus. Frederick Grant Banting - 1923: Extraction of insulin and treatment of diabetes. Alexander Fleming - 1945: Discovery of penicillin. Walter Rudolf Hess - 1949: Brain mapping for control of internal bodily functions. Werner Theodor Otto Forssmann - 1956: Cardiac catheterization. Charles Brenton Huggins - 1966: Hormonal control of prostate cancer. OPEN ACCESS Joseph Edward Murray - 1990: Organ transplantation. *Correspondence: Shinya Yamanaka-2012: Reprogramming of mature cells for pluripotency. Jayant Radhakrishnan, Department of Surgery and Urology, University of Emil Theodor Kocher (August 25, 1841 to July 27, 1917) Illinois, 1502, 71st, Street Darien, IL Kocher received the award in 1909 “for his work on the physiology, pathology and surgery of the 60561, Chicago, Illinois, USA, thyroid gland” [1]. -

Download The

ii Science as a Superpower: MY LIFELONG FIGHT AGAINST DISEASE AND THE HEROES WHO MADE IT POSSIBLE By William A. Haseltine, PhD YOUNG READERS EDITION iii Copyright © 2021 by William A. Haseltine, PhD All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. iv “If I may offer advice to the young laboratory worker, it would be this: never neglect an extraordinary appearance or happening.” ─ Alexander Fleming v CONTENTS Introduction: Science as A Superpower! ............................1 Chapter 1: Penicillin, Polio, And Microbes ......................10 Chapter 2: Parallax Vision and Seeing the World ..........21 Chapter 3: Masters, Mars, And Lasers .............................37 Chapter 4: Activism, Genes, And Late-Night Labs ........58 Chapter 5: More Genes, Jims, And Johns .........................92 Chapter 6: Jobs, Riddles, And Making A (Big) Difference ......................................................................107 Chapter 7: Fighting Aids and Aiding the Fight ............133 Chapter 8: Down to Business ...........................................175 Chapter 9: Health for All, Far and Near.........................208 Chapter 10: The Golden Key ............................................235 Glossary of Terms ..............................................................246 -

Scotland's Drug Scene

SULSA, JULY 2017 Scotland’s Drug Scene or many people, if asked about drugs led trypanosomes that are transmitted between in Scotland, they will think of Euan Ma- people by blood sucking tsetse fies. The new cgregor disappearing into the bowl of drug, called fexinidazole, or “fexi” for short, can be the “worst toilet in Scotland”, in Danny taken orally as tablets, rather than injections, as is Boyle’s flm rendition of Irvine Welsh’s the case for current sleeping sickness treatments. book “Train Spotting”. Drugs, however, It has been developed over the last 10 years by a Frepresent a critical part of the Scottish economy. Geneva-based group called the Drugs for Neglec- Not the damaging recreational kind, but the me- ted Diseases initiative (DNDi). It was frst shown to dicines that save lives. Scotland has been a global be active against the parasites by Frank Jennings pioneer in the discovery of new drugs. Here we whilst working at the School of Veterinary Me- outline some of Scotland’s landmark contribu- dicine in Glasgow in the 1980s. Alan Fairlamb, tions to this feld. working with the Drug Discovery Unit in Dundee, later showed that fexi is also active against another As early as the middle of the nineteen- neglected parasitic disease called leishmaniasis. th century, Scots were leading the way in drug Interest in developing drugs at the Glasgow vet development. Dr Livingstone, the missionary School had reached its pinnacle when James Bla- explorer from Blantyre near Glasgow, managed ck, from Uddingston, not far from Livingstone’s to navigate his way around Africa where others birthplace in Blantyre, began his research into un- had failed before, through his diligent use of the derstanding the efects of adrenaline on the heart. -

Nobel Laureates in Physiology Or Medicine

All Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine 1901 Emil A. von Behring Germany ”for his work on serum therapy, especially its application against diphtheria, by which he has opened a new road in the domain of medical science and thereby placed in the hands of the physician a victorious weapon against illness and deaths” 1902 Sir Ronald Ross Great Britain ”for his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it” 1903 Niels R. Finsen Denmark ”in recognition of his contribution to the treatment of diseases, especially lupus vulgaris, with concentrated light radiation, whereby he has opened a new avenue for medical science” 1904 Ivan P. Pavlov Russia ”in recognition of his work on the physiology of digestion, through which knowledge on vital aspects of the subject has been transformed and enlarged” 1905 Robert Koch Germany ”for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis” 1906 Camillo Golgi Italy "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system" Santiago Ramon y Cajal Spain 1907 Charles L. A. Laveran France "in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases" 1908 Paul Ehrlich Germany "in recognition of their work on immunity" Elie Metchniko France 1909 Emil Theodor Kocher Switzerland "for his work on the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid gland" 1910 Albrecht Kossel Germany "in recognition of the contributions to our knowledge of cell chemistry made through his work on proteins, including the nucleic substances" 1911 Allvar Gullstrand Sweden "for his work on the dioptrics of the eye" 1912 Alexis Carrel France "in recognition of his work on vascular suture and the transplantation of blood vessels and organs" 1913 Charles R. -

Nobel Laureates

Nobel Laureates Over the centuries, the Academy has had a number of Nobel Prize winners amongst its members, many of whom were appointed Academicians before they received this prestigious international award. Pieter Zeeman (Physics, 1902) Lord Ernest Rutherford of Nelson (Chemistry, 1908) Guglielmo Marconi (Physics, 1909) Alexis Carrel (Physiology, 1912) Max von Laue (Physics, 1914) Max Planck (Physics, 1918) Niels Bohr (Physics, 1922) Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (Physics, 1930) Werner Heisenberg (Physics, 1932) Charles Scott Sherrington (Physiology or Medicine, 1932) Paul Dirac and Erwin Schrödinger (Physics, 1933) Thomas Hunt Morgan (Physiology or Medicine, 1933) Sir James Chadwick (Physics, 1935) Peter J.W. Debye (Chemistry, 1936) Victor Francis Hess (Physics, 1936) Corneille Jean François Heymans (Physiology or Medicine, 1938) Leopold Ruzicka (Chemistry, 1939) Edward Adelbert Doisy (Physiology or Medicine, 1943) George Charles de Hevesy (Chemistry, 1943) Otto Hahn (Chemistry, 1944) Sir Alexander Fleming (Physiology, 1945) Artturi Ilmari Virtanen (Chemistry, 1945) Sir Edward Victor Appleton (Physics, 1947) Bernardo Alberto Houssay (Physiology or Medicine, 1947) Arne Wilhelm Kaurin Tiselius (Chemistry, 1948) - 1 - Walter Rudolf Hess (Physiology or Medicine, 1949) Hideki Yukawa (Physics, 1949) Sir Cyril Norman Hinshelwood (Chemistry, 1956) Chen Ning Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee (Physics, 1957) Joshua Lederberg (Physiology, 1958) Severo Ochoa (Physiology or Medicine, 1959) Rudolf Mössbauer (Physics, 1961) Max F. Perutz (Chemistry, 1962) -

Microbiologytoday

microbiologytoday microbiology vol36|feb09 quarterly magazine of the society today for general microbiology vol 36 | feb 09 the legacy of fleming ‘that’s funny!’: the discovery of penicillin what manner of man was fleming? the future of antibiotic discovery look who’s talking when good bugs fight bad contents vol36(1) regular features 2 News 38 Schoolzone 46 Hot off the Press 10 Microshorts 42 Gradline 49 Going Public 36 Conferences 45 Addresses 60 Reviews other items 33 The Defra-commissioned independent review of bovine tuberculosis research 54 Education Development Fund report 58 Obituary – Professor Sir James Baddiley FRS 59 Obituary – Emeritus Professor Naomi Datta FRS articles 12 ‘That’s funny!’: the 24 Look who’s talking! discovery and development Julian Davies of penicillin Antibiotics aren’t just for fighting infections; they are part of the bacterial signalling network. Kevin Brown The chance discovery of penicillin 80 years ago made Alexander Fleming a famous scientist. 28 When good bugs fight bad Roy Sleator 16 What manner of man was There are alternative methods available Alexander Fleming? for combating infectious diseases – not just antimicrobial chemotherapy. Philip Mortimer Alexander Fleming, the Society’s first President, did so much more than discover penicillin. 32 A precious memory Norberto Palleroni One of the few people left who met Fleming recounts his 20 Antibiotics and experience. Streptomyces: the future of antibiotic discovery 64 Comment: Debating creationism Flavia Marinelli Many options for drug discovery -

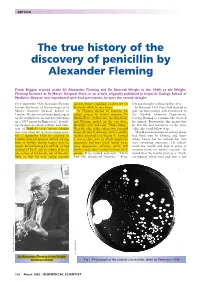

The True History of the Discovery of Penicillin by Alexander Fleming

ARTICLE The true history of the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming Frank Diggins trained under Sir Alexander Fleming and Sir Almroth Wright in the 1940s at the Wright- Fleming Institute at St Mary’s Hospital. Here, in an article originally published in Imperial College School of Medicine Gazette and reproduced with kind permission, he puts the record straight On 1 September 1928 Alexander Fleming scholar, Stuart Craddock, could work on left and thought nothing further of it. became Professor of Bacteriology at St his bench while he was away. In February 1928 Pryce had decided to Mary’s Hospital Medical School in As Fleming started to examine his give up bacteriology and transferred to London. He was an acknowledged expert culture plates, his former assistant, Dr the Morbid Anatomy Department, on the staphylococcus and was following Merlin Pryce, walked into the laboratory leaving Fleming to continue the research up a 1927 report by Bigger et al.1 describ- and Fleming picked up the top plate, by himself. Fortunately, this meant that ing changes in colour, texture and cohe- lifted the cover and said: “That’s funny.” he was the first person to see the peni- sion of Staphylococcus aureus colonies Near the edge of the culture was a mould cillin effect and follow it up. over time when left at room temperature. about 20 mm in diameter with a smaller Mould contamination on culture plates On 3 September 1928 he returned to satellite attached to it (Figure 1). Around had been seen by Fleming and many London from his home in Suffolk, having it was a clear area in which organisms others before but he realised that here been on holiday during August with his apparently had been lysed; further away was something important.