CHAPTER 8 CONSERVATION J. G. Mckern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

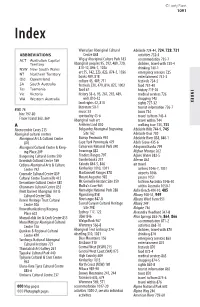

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

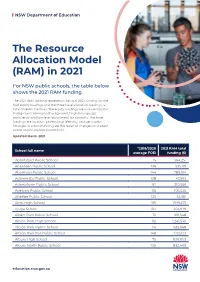

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Matters of National Environmental Significance Report

Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT D SITE ACCESS PLANS September 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 99 Gold Coast Quarry EIS ATTACHMENT E SITE TOPOGRAPHY September 2013 Cardno Chenoweth 99 Pacific Motorway 176 176 RP899491 RP899491 N 6889750 m E 539000 m E 539250 m E 539500 m E 539750 m E 540000 m E 540250 m E 540500 m E 540750 m E 541000 m E 541250 m E 541500 m N 6889750 m 903 905 SP210678 SP245339 144 905 WD4736 SP245339 N 6889500 m N 6889500 m Old Coach Road 22 SP238363 N 6889250 m N 6889250 m N 6889000 m N 6889000 m 103 105 5 SP127528 SP144215 RP162129 Barden Ridge Road 103 SP127528 Chesterfield Drive N 6888750 m N 6888750 m 1 RP106195 4 RP162129 RP853810 RP162129 927 6 4 5 SP220598 RP853810 3 RP854351 RP162129 2 N 6888500 m 5 N 6888500 m RP803474 SP105668 12 WD6568 SP105668 7 11 1 SP187063 105 2 3 F:\Jobs\1400\1454 Cardno Boral_Tallebudgera GCQ\000 Generic\Drawings\1454_017 Topography_aerial.dwg 15 SP144215 RP812114 RP803474 RP903701 1 Tallebudgera Creek Road 3 RP148506 FILE NAME: 13 RP803474 SP105668 901 RP907357 2 3 RP803474 SP187063 RP164840 6 N 6888250 m N 6888250 m 14 SP105668 600 SP251058 3 JOB SUB #: 901 1 SP145343 RP205290 RP148504 2 27 Samuel Drive 104 RP811199 RP190638 RP180320 2 8 October 2012 30 2 RP180320 SP150481 N 6888000 m RP838498 31 N 6888000 m RP180321 E 539000 m E 539250 m E 539500 m E 539750 m E 540000 m E 540250 m E 540500 m E 540750 m E 541000 m E 541250 m E 541500 m CREATED: REV DESCRIPTION DATE BY Legend: PROJECT: TITLE: Site Boundary Tallebudgera Figure 13 - Aerial Photo and Topography Photography: Nearmap. -

Montague Island Seabird Habitat Restoration Project

Montague Island Seabird Habitat Restoration Project Proceedings of Shared Island Management Workshop Narooma, NSW, November 2008 Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW Cover photos clockwise from left: www.geoffcomfort.com; S. Cohen, DECCW; S. Donaldson; DECCW. Inset bird: DECCW Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74232 337 4 DECCW 2009/443 November 2009 Printed on environmentally sustainable stock B Contents Preface ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1 Overview -

NESTING of the SOOTY SHEARWATER in AUSTRALIA the First Recorded Breeding of the Sooty Shearwater Al

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS NESTING OF THE SOOTY SHEARWATER IN AUSTRALIA The first recorded breeding of the Sooty Shearwater al. (1971) who listed Little Witch Island (Flat Witch Puffinus griseus in Australia was reported by Rohu Island in the Maatsuyker Group), Flat (Mutton Bird) (1914). He collected a specimen and "eggs" on 29 Island, Breaksea Island and Green (Hobbs) Island as December 1912 on Broughton Island, NSW. A check of breeding stations; these locations were published on in- the H.L. White Collection in the National Museum, formation received from C. Pitt, a former Surveyor- Melbourne, revealed that a "clutch of one egg ..." was General and Secretary for Lands in Tasmania, in March collected. Since that first report a number of published 1947. Pizzey (1980) also listed these locations except records have appeared; all refer to islands off New that he recorded Maatsuyker Island as the breeding sta- South Wales and Tasmania. tion apparently instead of Flat Witch Island in the Maatsuyker Group. No doubt his source of information In New South Wales, the Sooty Shearwater has also was that already published. been recorded breeding on Lion Island (Keast & McGill 1948), Little Broughton Island (Hindwood & D'Om- The additional locations supplied by Pitt all occur in brain 1960), Montague Island (Robinson 1964), Bird south-western Tasmania and, at the time of his report, Island (Lane 1965), Boondelbah Island (Morris et al. very little was known about the distribution of these 1973), Bowen Island (Lane 1975a), Tollgate Islands birds in this area. In those days, most reports originated (McKean & Fullagar 1976) and Cabbage Tree Island from fishermen, or lighthouse-keepers stationed on (Fullagar 1976). -

BOOKBINDING .;'Ft1'

• BALOS BOOKBINDING .;'fT1'. I '::1 1 I't ABORIGINAL SONGS FROM THE BUNDJALUNG AND GIDABAL AREAS OF SOUTH-EASTERN AUSTRALIA by MARGARET JANE GUMMOW A thesis submitted in fulfihnent ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department ofMusic University of Sydney July 1992 (0661 - v£6T) MOWWnO UllOI U:lpH JO .uOW:lW :lip Ol p:ll1l:>W:l<J ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I wish to express my most sincere thanks to all Bundjalung and Gidabal people who have assisted this project Many have patiently listened to recordings ofold songs from the Austra1ian Institute ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, sung their own songs, translated, told stories from their past, referred me to other people, and so on. Their enthusiasm and sense ofurgency in the project has been a continual source of inspiration. There are many other people who have contributed to this thesis. My supervisor, Dr. Allan Marett, has been instrumental in the compilation of this work. I wish to thank him for his guidance and contributions. I am also indebted to Dr. Linda Barwick who acted as co-supervisor during part of the latter stage of my candidature. I wish to thank her for her advice on organising the material and assistance with some song texts. Dr. Ray Keogh meticulously proofread the entire penultimate draft. I wish to thank him for his suggestions and support. Research was funded by a Commonwealth Postgraduate Research Award. Field research was funded by the Austra1ian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Several staff members at AlATSIS have been extremely helpful. -

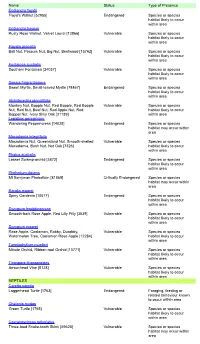

Name Status Type of Presence Floyd's Walnut

Name Status Type of Presence Endiandra floydii Floyd's Walnut [52955] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Endiandra hayesii Rusty Rose Walnut, Velvet Laurel [13866] Vulnerable Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Floydia praealta Ball Nut, Possum Nut, Big Nut, Beefwood [15762] Vulnerable Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Fontainea australis Southern Fontainea [24037] Vulnerable Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Gossia fragrantissima Sweet Myrtle, Small-leaved Myrtle [78867] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Hicksbeachia pinnatifolia Monkey Nut, Bopple Nut, Red Bopple, Red Bopple Vulnerable Species or species Nut, Red Nut, Beef Nut, Red Apple Nut, Red habitat likely to occur Boppel Nut, Ivory Silky Oak [21189] within area Lepidium peregrinum Wandering Pepper-cress [14035] Endangered Species or species habitat may occur within area Macadamia integrifolia Macadamia Nut, Queensland Nut, Smooth-shelled Vulnerable Species or species Macadamia, Bush Nut, Nut Oak [7326] habitat likely to occur within area Phaius australis Lesser Swamp-orchid [5872] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Phebalium distans Mt Berryman Phebalium [81869] Critically Endangered Species or species habitat may occur within area Randia moorei Spiny Gardenia [10577] Endangered Species or species habitat likely to occur within area Syzygium hodgkinsoniae Smooth-bark Rose Apple, Red Lilly Pilly [3539] Vulnerable Species or species -

5Th Australasian Ornithological Conference 2009 Armidale, NSW

5th Australasian Ornithological Conference 2009 Armidale, NSW Birds and People Symposium Plenary Talk The Value of Volunteers: the experience of the British Trust for Ornithology Jeremy J. D. Greenwood, Centre for Research into Ecological and Environmental Modelling, The Observatory, Buchanan Gardens, University of St Andrews, Fife KY16 9LZ, Scotland, [email protected] The BTO is an independent voluntary body that conducts research in field ornithology, using a partnership between amateurs and professionals, the former making up the overwhelming majority of its c13,500 members. The Trust undertakes the majority of the bird census work in Britain and it runs the national banding and the nest records schemes. The resultant data are used in a program of monitoring Britain's birds and for demographic analyses. It runs special programs on the birds of wetlands and of gardens and has undertaken a series of distribution atlases and many projects on particular topics. While independent of conservation bodies, both voluntary and statutory, much of its work involves the provision of scientific evidence and advice on priority issues in bird conservation. Particular recent foci have been climate change, farmland birds (most of which have declined) and woodland birds (many declining); work on species that winter in Africa (many also declining) is now under way. In my talk I shall describe not only the science undertaken by the Trust but also how the fruitful collaboration of amateurs and professionals works, based on their complementary roles in a true partnership, with the members being the "owners" of the Trust and the staff being responsible for managing the work. -

Western South Pacific Regional Workshop in Nadi, Fiji, 22 to 25 November 2011

SPINE .24” 1 1 Ecologically or Biologically Significant Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 413 rue St-Jacques, Suite 800 Tel +1 514-288-2220 Marine Areas (EBSAs) Montreal, Quebec H2Y 1N9 Fax +1 514-288-6588 Canada [email protected] Special places in the world’s oceans The full report of this workshop is available at www.cbd.int/wsp-ebsa-report For further information on the CBD’s work on ecologically or biologically significant marine areas Western (EBSAs), please see www.cbd.int/ebsa south Pacific Areas described as meeting the EBSA criteria at the CBD Western South Pacific Regional Workshop in Nadi, Fiji, 22 to 25 November 2011 EBSA WSP Cover-F3.indd 1 2014-09-16 2:28 PM Ecologically or Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Biologically Significant ISBN: 92-9225-558-4 Copyright © 2014, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Marine Areas (EBSAs) The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of Special places in the world’s oceans its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Secretariat of the Areas described as meeting the EBSA criteria at the Convention on Biological Diversity. CBD Western South Pacific Regional Workshop in Nadi, This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. -

RECONCILIATION TRAIL - Armidale to Myall Creek

1 RECONCILIATION TRAIL - Armidale to Myall Creek As we start off in Armidale and travel to Mt Yarrawyck, Tingha, Goonawigall, Inverell, Cranky Rock and Myall Creek we are making a long curving path that joins onto the one at the Memorial site which for Aboriginal people speaks of the path of the Rainbow Serpent moving through the land and creating the features of the landscape. Aboriginal language groups in the area https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/articles/aiatsis- map-indigenous-australia Who belongs to this land? The traditional custodians of the New England Region are the Anaiwan people living around Armidale and Tingha and the Kamilaroi around Inverell. The Anaiwan language is being revived and taught. The Kamilaroi nation is the second largest in Eastern Australia after the Waradjuri land that lies further south and west of the Blue Mountains. The Kamilaroi (pronounced Gamilaroi) inhabited a large country, stretching from as far as the Hunter Valley in NSW through to Nindigully in Qld and as far west as the Warrumbungle Mountains near Coonabarabran. They maintained fertile soil, running rivers and streams, and plentiful fish supplies. Today, descendants of the traditional people of the 2 Kamilaroi Nation continue to occupy these lands. They are known as 'Murri' people. The towns in their country include Moree, Inverell, Narrabri and Gunnedah. The Kamilaroi (Gamilaraay language) belong to Australia's largest language family, the Pama- Nyungan. Before 1788 this language family covered 90% of the country and comprised hundreds of languages. Today the Gamilaraay language remains an important part of Kamilaroi heritage. Although there are no fluent speakers, the language is being reconstructed from recordings and dictionaries, and is being taught by Kamilaroi people. -

CYCA History Timeline Contents

CYCA History Timeline Contents 1942 - 1949 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 1950 - 1959 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1960 - 1969 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 13 1970 – 1979 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 18 1980 - 1989 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 24 1990 - 1999 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 30 2000 - 2009 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 36 2010 – 2019 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 43 2020 – Current -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 56 1942 - 1949 31/05/1942 Future SHYR Radio Relay Vessel, Lauriana intercepts Japanese miniature submarine at Sydney Harbour’s wartime boom net near Watsons Bay. When the charge went off it lifted her transom clear of the water. Lauriana sometime later during WWII transported General MacArthur in the Pacific. Other future member’s yachts used by RAN during WWII -

Breeding Biology of Gould's Petrels Pterodroma

BREEDING BIOLOGY OF GOULD’S PETRELS PTERODROMA LEUCOPTERA: PREDICTING BREEDING OUTCOMES FROM A PHYSIOLOGICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF ADULTS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Terence W. O’Dwyer, BEnvSc (Hons) SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES 2004 CERTIFICATION I, Terence William O’Dwyer, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. ii ABSTRACT 1) The breeding biology of Gould’s petrels Pterodroma leucoptera was studied at Cabbage Tree Island, New South Wales over three successive breeding seasons from 2000/01. I sought to identify better reproductively performing individuals and to identify indicators of breeding success through a physiological and morphological appraisal of adult characteristics. 2) Gould’s petrels exhibit no sex linked plumage dimorphism, however, knowledge of the sex of both adults and chicks was an integral component of this study. Blood samples were taken from 209 adults and 206 chicks and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based molecular technique was used to determine their sex. With the knowledge of the sex of individuals a discriminant function analysis (DFA) based on several skeletal measures was developed. The DFA could predict the sex of adults with an accuracy of about 85% and chicks with an accuracy of 66%. 3) Relationships between egg laying characteristics and hatching success were assessed.