A Look at Grit: Teachers Who Teach Students with Severe Disabilities Donna Baker Martin Brandman, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Guided Historical Walking Tour of Downtown Williamsport One Mile, Approximately 30 Minutes

Williamsport, Pennsylvania www.williamsportarts.com Self Guided Historical Walking Tour of Downtown Williamsport One mile, approximately 30 minutes. Begin at the Visitors Information Center off William St. west of the Hampton Inn. Until urban renewal in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the area to the east of the Visitors Information Center was known as Little Italy because most of its inhabitants and storekeepers were Italian immigrants and their descendants. Go north on William Street to the intersection of William and Third Streets. On the northwest corner is site #1. 1. The Grit Building, 200-222 West Third Street (1892) The Grit began in 1882 as a Saturday afternoon supplement to the Daily Sun and Banner. Printer Dietrick Lamade bought out his partner in 1884 and turned the Grit into an independent Sunday newspaper that grew to become known as “American’s greatest family newspaper.” Avoiding the “yellow journalism” of post-Civil War newspapers and instead, catering to the rising Victorian middle class, the newspaper focused on the goals and values of a family-oriented audience. The paper remained in the Lamade family until it was sold and relocated to Topeka, Kansas, in 1992. The original building on the corner was renovated for re-use. With its rounded arches, deep window and door reveals, and contrasting bands of colors, the building’s façade refl ects the uniquely American Romanesque Revival style of architect H.H. Richardson (1838-1886) 2. The Old Jail, 154 West Third Street (1868) On the northeast corner stands the second Lycoming County Jail, built after fi re destroyed the original structure that has served the county since 1799. -

Program Guide April 12-13, 2014 = Asheville, N.C

MOREMORE THTHANAN 1515 0 0 WORKSHOPS!WORKSHOPS! PP.. 88 EECCO-FRIEO-FRIENNDLYDLY MMAARKETPLRKETPLACACEE PP.. 2727 OFF-STOFF-STAAGEGE DDEMOEMONNSTRSTRAATIOTIONNSS PP.. 2222 KEYKEYNNOTEOTE SPESPEAAKERSKERS PP.. 77 PROGRAM GUIDE APRIL 12-13, 2014 = ASHEVILLE, N.C. 2 www.MotherEarthNewsFair.com Booths 2419, 2420, 2519 & 2520 DISCOVER The Home of Tomorrow, Today Presented by Steve Linton President, Deltec Homes Renewable Energy Stage Check Fair schedule for details LEARN Deltec Homes Workshop Presented by Joe Schlenk Director of Marketing, Deltec Homes Davis Conference Room Check Fair schedule for details ENGAGE Tour our plant on Friday, April 11 Deltec Homes RSVP 800.642.2508 Ext 801 deltechomes.com 69 Bingham Rd Asheville Visit our Model Home in Mars Hill, NC Tel 800.642.2508 Thursday, Friday & Saturday, 10 am - 5 pm 828-253-0483 MOTHER EARTH NEWS FAIR 3 omes, H e are particularlye are Grit l W Motorcycle Classics Motorcycle l eader R ept. 12-14, 2014 S Utne Utne l ourles. They represent some of the mostrepresent ourles. They esort, ct. 25-26, 2014 T R M-7:00 PM O M-5:00 PM A A Gas Engine Magazine Magazine Engine Gas l tephanie S nimal Nutrition and Yanmar. Yanmar. and nimal Nutrition A Mother Earth Earth Mother tate Fairgrounds, May 31-June 1, 2014 31-June May tate Fairgrounds, S hours: 9:00 Mother Earth Earth Mother hours: 9:00 Mother Earth News News Earth Mother prings Mountain prings Mountain S alatin and Fair Mother Earth Living Mother l Fair S even even ashington S FAIR HOURS FAIR Capper’s Farmer Farmer Capper’s l unday W aturday aturday S S around the country. -

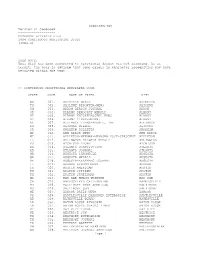

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

Program Guide

MORE THAN 150 WORKSHOPS! P. 7 ECO-FRIENDLY MARKETPLACE P. 20 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS P. 6 OFF-STAGE DEMONSTRATIONS P. 18 PROGRAM GUIDE 1 www.MotherEarthNewsFair.comOCTOBER 12-13, 2013 LAWRENCE, KS. MOTHER EARTH NEWS FAIR 1 Save up to 50% on your heating and cooling costs. Icynene insulation gets into spaces that others can’t. Icynene spray foam insulation completely seals and insulates your home letting you save as much as 50% in your monthly heating and cooling bills. Visit our website and discover the 5 easy steps to choosing the right insulation for your home. Let us fi ll you in. Visit us at the Mother Earth Fair - Booth 120 & 124 Visit www.icynene.com The Evolution of InsulationTM Motorcycle Classics Motorcycle l Utne Reader Utne l The sunflower is the official state flower of Kansas is the official state The sunflower Gas Engine Magazine Magazine Engine Gas l Mother Earth Living Mother l Capper’s Capper’s l 2014 FAIR DATES 2014 FAIR and is featured on the Kansas state quarter and flag, and inspired the state’s the state’s on the Kansas state quarter and flag, and inspired and is featured State. Sunflower nickname: The ON THE COVER: Laura Perkins. by Photo Lawrence, Kan., location and dates to be determined Lawrence, Mother Earth News Earth News Mother Farm Collector Farm l Puyallup, Wash., Washington State Fairgrounds, May 31-June 1, 2014 31-June May Fairgrounds, State Washington Wash., Puyallup, Seven Springs, Pa., Seven Springs Mountain Resort, Sept. 12-14, 2014 Sept. Resort, Mountain Springs Seven Pa., Springs, Seven Asheville, N.C., Western North Carolina Agricultural Center, April 12-13, 2014 April Agricultural Center, Carolina North Western Asheville, N.C., Grit Grit LAWRENCE, KS. -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal. -

Grip the Strange World of Men 1St Edition Free Download

FREE GRIP THE STRANGE WORLD OF MEN 1ST EDITION PDF Gilbert Hernandez | 9781616558307 | | | | | Grit (newspaper) - Wikipedia Grit is a magazine, formerly a weekly newspaperpopular in the rural U. It carried the subtitle "America's Greatest Family Newspaper". In the early s, Grip The Strange World of Men 1st edition targeted small town and rural families with 14 pages plus a fiction supplement. The family moved to Williamsport inwhere Johannes died of typhoid fever on January 1, To support the family, Dietrick, his sister, and his older brothers quit school. At 18, Lamade began printing theater programs and a four-page ad brochure, the Merchants' Free Press. In the summer ofhe did Camp News for the Pennsylvania National Guardand he married the following year. InLamade became the ad compositor and assistant composing room foreman for the Daily Sun and Bannerand that same year, Grit began as the paper's Saturday edition, typeset by Lamade. He left the Daily Sun in to launch the weekly Times as a daily, but finances and the health of the owner led the Grip The Strange World of Men 1st edition to cease publication. With two children and no job, year-old Lamade became a publisher. Teaming with two partners, he bought the Times equipment plus the Grit name and goodwill. During his first year, he increased Grit' s circulation to 4, He operated from a third-floor single room, moving to a storefront location inestablishing a weekly circulation of 20, by With rapid expansion, a wagon of Remington typewriters was delivered to the Grit offices in Kahleslater famed as the creator of the long-run comic strip Hairbreadth Harry. -

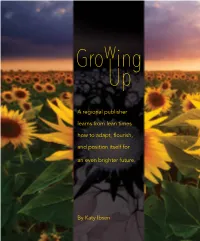

A Regional Publisher Learns from Lean Times How to Adapt, Flourish, and Position Itself for an Even Brighter Future

Growing Up A regional publisher learns from lean times how to adapt, flourish, and position itself for an even brighter future. By Katy Ibsen 10 Pages - Winter 2018 Growing Up Growing Up A regional publisher learns from lean times how to adapt, flourish, and position itself for an even brighter future pagesthemagazine.com 11 Growing Up t was spring of 2017, just shy of the one-year anniversary of our acquisition by a larger publishing company. I sat across the table from our various new directors, reviewing Sunflower Publishing’s Ibusiness strategy. We’re a small city/regional magazine publishing group. Our new owner, Ogden Publications, Inc., is a national consumer magazine publisher. With a pinch of pride, I ran through the many titles we publish, the clients with whom we work, and the seven full-time employees who make up our staff. We were on pace for 67 publishing events for the year. Of that tally, 52 percent was self-published work and 48 percent was custom publishing. We had forecasted over $1.7 million in gross revenue with a near 30 percent profit margin. As I digested my own spoken words, I realized why our new ownership had been so intrigued with Sunflower Publishing: We had created an efficient and profitable approach to city/regional publishing. Growth Interrupted Sunflower Publishing began in 2003 as the magazine publishing division of a 100-year-old, family-owned newspaper company, The World Company, in Lawrence, Kansas. In 2004, we launched our first local city title, Lawrence Magazine. When I started in 2005, I was an intern-turned-editor overseeing Sunflower Publishing’s second magazine, the biannual collegiate publication Chalk, which served the community’s student market. -

Mother Earth Living Media

Mother Earth Living • 1503 SW 42nd St. • Topeka,2020 KS 66609 MEDIA• 800.678.5779 • [email protected] • www.MotherEarthLiving.com Reach Out to Women Invested in Their Health The number of people interested in managing their health, preventing chronic ailments and aging gracefully grows every year. For an example, we can look to the explosive rise of the natural health supplements market — valued at approximately $36 million in 2016, this market is expected to reach $68 million by the end of 2024. More and more, people realize the keys to good health are found in nature: nutritious, organic foods; moving our bodies daily; and lifestyle habits that emphasize stress management, time spent outdoors and a connection with others. Despite the seeming simplicity of this advice, living well and maintaining our health is a perennially complex topic in our modern world. Mother Earth Living acts as a reliable friend and guide to those interested in creating a healthy home and lifestyle for themselves and their families, a trusted resource readers turn to for science-backed information and high-quality product recommendations. As an advertiser, you become a part of that voice and a critical resource to this important block of consumers, reaching engaged sustainable lifestyle consumers via one easy, targeted and effective buy. Mother Earth Living • 1503 SW 42nd St. • Topeka, KS 66609 • 800.678.5779 • [email protected] • www.MotherEarthLiving.com AUDIENCE RESEARCH THEY STAY HEALTHY NATURALLY 91% eat organic food regularly 81% use vitamin supplements daily 70% exercise regularly 69% use essential oils regularly 62% drink tea daily THEY FEED THEIR FAMILIES HOMEGROWN PRODUCE 99% garden 92% feel it is important to use organic gardening methods 90% grow herbs THEY PAY ATTENTION TO THEIR NUTRITION 93% cook from scratch 87% bake from scratch 74% use herbs in food preparation Source: 2019 Custom Study Mother Earth Living • 1503 SW 42nd St. -

The Examination of Grit in California Superintendents Jacqueline Kearns Brandman University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Brandman University Brandman University Brandman Digital Repository Dissertations Fall 10-10-2015 The Examination of Grit in California Superintendents Jacqueline Kearns Brandman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.brandman.edu/edd_dissertations Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Educational Leadership Commons Recommended Citation Kearns, Jacqueline, "The Examination of Grit in California Superintendents" (2015). Dissertations. 213. https://digitalcommons.brandman.edu/edd_dissertations/213 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Brandman Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Brandman Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Examination of Grit in California Superintendents A Dissertation by Jacqueline Kearns Brandman University Irvine, California. School of Education Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership October 2015 Committee in charge: Philip Pendley, Ed.D., Committee Chair Keith Larick, Ed.D. Marylou Wilson, Ed.D. The Examination of Grit in California Superintendents Copyright © 2015 by Jacqueline Kearns iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There is no way I could have completed this dissertation on my own. I first must acknowledge and give recognition to Jesus Christ in giving me the ability, opportunity, and perseverance to accomplish this goal that has been on my heart since a young child. My family: my son, my mom, and my dad. You have been my support to keep going and accommodating when I needed the extra help. -

Journal of the Lycoming County Historical Society, Spring 1968

24 THE JOU RNAL Miss Audrev E. Neuhard Miss Virginia Mae Springman M rs. Frances R. Nicholson Mi's. Russell I Sprout Miss Verna G. No11 Ando'ew Spulet' Eva M. Norman Charles XXr. Spuler, Ji Charles E. Noyes, Sr. Mrs. Jack R. Stabley Mrc John Stahlnecker Rlrs Harry Staib J. Michael Ocl)s ATt'. Leslie Stanle\. Arthur D. Ohl Mrs. Julia M. Staves George E. Orwig, ll A/Ir. Tllomas L. Stearns Harry M. Ott M ]'. Carl FI. Steele Blr. \william Stern Dr. C. C. Pagans Nlrs Joseph Stewart MissHelen C. Page James L Stopper Dr. GeorgeParks Mls. If<lathi'yn Stover Mrs. Eleanor .A.. Parknaan Mr. John W. Strawbridge, lll A'lrs. Marie S. Parkman Mrs. Lois E. St.loud Mrs. Ralpll G. Parsons Mrs. Loretta \4r. Swank Mr. Wiiliain Paynter Mr. Chas. A. Szybist Miss Zella Peppennan Miss Ethel Peters Mr. ThomasT. Tiber Mrs. ChesterPeterson A/Irs. A. S. Ta},lor Anna E. Pfaff Mt's. Margaret M. Taylor William F. Plankenhorn Bliss Mary Louise Taylor Mr. LosingB. Priest Helen G. TenBroeck Mrs. Arthur K. Thomas Bliss Catherine E. Thompson Charles Rainow Di '. Richard IB. Tobias Mrs. J. E. Raker Grace J. Tomb Mr. Edward Ranck Miss Gladys Tozier Mrs. Hazel N. Rathmell Miss Helen S. Trafford John N. Reedy Alice Tule Hon. Karl IB. Reichai'd William A. Turnbaugh M rs. Isabella Reithoffer DEC EMBE R, 1960 Ray D. Rhoades NOVEMBE R, 1967 Kenneth D. Rhone Mrs. Franltlin T. Ulnlan Norman R. Richards Mary E. Ulmei' Miss Mary E. Riddell Edward Utz SEVEN YEARS OF PROGRESS Mr. -

Grit: a Short History of a Useful Concept

Journal of Educational Controversy Volume 10 Number 1 10th Year Anniversary Issue Article 3 2015 Grit: A Short History of a Useful Concept Ethan W. Ris Stanford University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/jec Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Ris, Ethan W. (2015) "Grit: A Short History of a Useful Concept," Journal of Educational Controversy: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/jec/vol10/iss1/3 This Continuing the Conversation is brought to you for free and open access by the Peer-reviewed Journals at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Educational Controversy by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grit: A Short History of a Useful Concept Cover Page Footnote The author wishes to thank David Labaree and Philo Hutcheson for their commentary on versions of this paper. This continuing the conversation is available in Journal of Educational Controversy: https://cedar.wwu.edu/jec/vol10/ iss1/3 Ris: Grit: A Short History of a Useful Concept Grit: A Short History of a Useful Concept Ethan W. Ris Stanford University Graduate School of Education The character trait “grit” is a much-discussed and debated topic, both among education researchers and in public forums. Employing longitudinal discourse analysis, this paper examines the history of grit over more than a century, paying special attention to the ways in which adults have attempted to inculcate it in children. The author finds that current discussion of grit’s salience for the education of disadvantaged students ignores the rich historical context of a long-sought trait, which in fact has usually been the focus of anxiety from middle and upper-class parents and educators. -

One College Avenue

One College Avenue Growing Enthusiasm Alumni share inspiring careers at public garden see page 16 Also in this Issue: p. 4 Best Beach Books p. 8 Alumnus Witnesses the Meaning of Victory p. 10 A Tradition of “Nontraditional” Careers SPRING 2010 SPRING One College Avenue, published online and as a quarterly magazine, is dedicated to sharing the educational development, goals, and achievements of Pennsylvania College of Technology students, alumni, faculty and staff with one another and with the greater community. Please visit One College Avenue online at www.pct.edu/oca ISSUE EDITOR ONE COLLEGE AVENUE Jennifer A. Cline ADVISORY COMMITTEE L. Lee Janssen CONTRIBUTING news editor EDITORS Williamsport Sun-Gazette Elaine J. Lambert ’79 Lana K. Muthler Tina M. Miller ’03 news editor The Express, Lock Haven Tom Wilson Joseph S. Yoder Robert O. Rolley publisher ISSUE DESIGNER The Express, Lock Haven Sarah K. Patterson ’05 Joseph Tertel e-marketing consultant DESIGN & DIGITAL JPL Productions, Harrisburg PRODUCTION Penn College Members Larry D. Kauffman Valerie L. Fessler Heidi Mack director of alumni relations Deborah K. Peters ’97 Barbara A. Danko K. Park Williams ’80 retired director of alumni relations WEB DESIGN Sandra Lakey faculty Judy A. Fink ’95 speech communication and composition Phillip C. Warner ’06 Brad L. Nason ALUMNI NOTES faculty mass communications Connie Funk Eugne M. McAvoy CONTRIBUTING assistant dean PHOTOGRAPHERS School of Integrated Studies Jennifer A. Cline Ashlyn M. Hershberger, Larry D. Kauffman vice president of public relations Student Government Association Cindy Davis Meixel Jessica L. Tobias Tom Wilson Davie Jane Gilmour, Ph.D. Joseph S. Yoder President Pennsylvania College Other photos as credited Of Technology One College Avenue, published by the College Information & Community Relations Office, considers for publication materials submitted by students, alumni, faculty, staff and others including letters to the editor, alumni notes and other information.