Grit: a Short History of a Useful Concept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russia You Never Met

The Russia You Never Met MATT BIVENS AND JONAS BERNSTEIN fter staggering to reelection in summer 1996, President Boris Yeltsin A announced what had long been obvious: that he had a bad heart and needed surgery. Then he disappeared from view, leaving his prime minister, Viktor Cher- nomyrdin, and his chief of staff, Anatoly Chubais, to mind the Kremlin. For the next few months, Russians would tune in the morning news to learn if the presi- dent was still alive. Evenings they would tune in Chubais and Chernomyrdin to hear about a national emergency—no one was paying their taxes. Summer turned to autumn, but as Yeltsin’s by-pass operation approached, strange things began to happen. Chubais and Chernomyrdin suddenly announced the creation of a new body, the Cheka, to help the government collect taxes. In Lenin’s day, the Cheka was the secret police force—the forerunner of the KGB— that, among other things, forcibly wrested food and money from the peasantry and drove some of them into collective farms or concentration camps. Chubais made no apologies, saying that he had chosen such a historically weighted name to communicate the seriousness of the tax emergency.1 Western governments nod- ded their collective heads in solemn agreement. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank both confirmed that Russia was experiencing a tax collec- tion emergency and insisted that serious steps be taken.2 Never mind that the Russian government had been granting enormous tax breaks to the politically connected, including billions to Chernomyrdin’s favorite, Gazprom, the natural gas monopoly,3 and around $1 billion to Chubais’s favorite, Uneximbank,4 never mind the horrendous corruption that had been bleeding the treasury dry for years, or the nihilistic and pointless (and expensive) destruction of Chechnya. -

Download Article

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 65 1st International Conference on Economics, Business, Entrepreneurship, and Finance (ICEBEF 2018) The Influence of Personality and Grit on The Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Examining the Mediating Roles of Job Involvement: Survey on lecturers at higher education of the ministry of industry in Indonesia M. Arifin Hesi Eka Puteri Polytechnic ATI Padang State Institute for Islamic Studies of Bukittinggi Padang, Indonesia Bukittinggi, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—This study investigates whether personality and One interesting problem in higher education is the issue grit affect the Organizational Citizenship Behavior and if so, about the extra-role behavior. Although the higher education whether the effect is mediated by job involvement or not. Using a law in many countries clearly regulates the lecturer’s sample of 132 lecturers of Higher Education of The Ministry of performance, but its only evaluates the in-role behavior not the Industry in Indonesia in 2018, this research revealed that extra-role behavior. The concept of extra-role behavior is personality and grit are positively related to the organizational reflected in what is called the Organizational Citizenship citizenship behavior. This study proves that there is relationship Behavior (OCB). Schnake defined OCB as "functional, extra- between personality and grit with organizational citizenship role, pro-social behavior, directed at individuals, group and behavior, and this relationship is partially mediated by job organization" [4]. While Organ defined Organizational involvement. These empirical findings reinforce previous Citizenship Behavior as anything that employees choose to do, researches about the relationship between personality and organizational citizenship behavior. -

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

Student Perceptions of Grit, Emotional-Social Intelligence, And

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2015 Student Perceptions of Grit, Emotional-Social Intelligence, and the Acquisition of Non-Cognitive Skills in the Cristo Rey Corporate Work Study Program Don Gamble University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, and the Educational Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Gamble, Don, "Student Perceptions of Grit, Emotional-Social Intelligence, and the Acquisition of Non-Cognitive Skills in the Cristo Rey Corporate Work Study Program" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 303. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/303 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco STUDENT PERCEPTIONS OF GRIT, EMOTIONAL-SOCIAL INTELLIGENCE, AND THE ACQUISITION OF NON-COGNITIVE SKILLS IN THE CRISTO REY CORPORATE WORK-STUDY PROGRAM A Dissertation Presented To The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Catholic Educational Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment -

GRIT META-ANALYSIS 1 Much Ado About Grit

GRIT META-ANALYSIS 1 Much Ado about Grit: A Meta-Analytic Synthesis of the Grit Literature Marcus Credé Department of Psychology, Iowa State University [email protected] Michael C. Tynan Department of Psychology, Iowa State University [email protected] Peter D. Harms School of Management, University of Alabama [email protected] ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION: JOURNAL OF PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY (Not the Paper of Record) Corresponding Author: Marcus Credé, Department of Psychology, W112 Lagomarcino Hall, 901 Stange Road, Iowa State University, Ames, 50011-1041, [email protected]. GRIT META-ANALYSIS 2 Abstract Grit has been presented as a higher-order personality trait that is highly predictive of both success and performance and distinct from other traits such as conscientiousness. This paper provides a meta-analytic review of the grit literature with a particular focus on the structure of grit and the relation between grit and performance, retention, conscientiousness, cognitive ability, and demographic variables. Our results based on 584 effect sizes from 88 independent samples representing 66,807 individuals indicate that the higher-order structure of grit is not confirmed, that grit is only moderately correlated with performance and retention, and that grit is very strongly correlated with conscientiousness. We also find that the perseverance of effort facet has significantly stronger criterion validities than the consistency of interest facet and that perseverance of effort explains variance in academic performance even after controlling for conscientiousness. In aggregate our results suggest that interventions designed to enhance grit may only have weak effects on performance and success, that the construct validity of grit is in question, and that the primary utility of the grit construct may lie in the perseverance facet. -

Full Press Release

Press Contacts Michelle Perlin 212.590.0311, [email protected] aRndf Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] THE LIFE OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU THROUGH THE LENS OF HIS REMARKABLE JOURNAL IS THE SUBJECT OF A NEW MORGAN EXHIBITION This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal June 2 through September 10, 2017 New York, NY, April 17, 2017 — Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) occupies a lofty place in American cultural history. He spent two years in a cabin by Walden Pond and a single night in jail, and out of those experiences grew two of this country’s most influential works: his book Walden and the essay known as “Civil Disobedience.” But his lifelong journal—more voluminous by far than his published writings—reveals a fuller, more intimate picture of a man of wide-ranging interests and a profound commitment to living responsibly and passionately. Now, in a major new exhibition entitled This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal opening June 2 at the Morgan Library & Museum, nearly one hundred items Benjamin D. Maxham (1821–1889), Henry D. Thoreau, have been brought together in the most comprehensive Daguerreotype, Worcester, Massachusetts, June 18, 1856. Berg Collection, New York Public Library. exhibition ever devoted to the author. Marking the 200th anniversary of his birth and organized in partnership with the Concord Museum in Thoreau’s hometown of Concord, Massachusetts, the show centers on the journal he kept throughout his life and its importance in understanding the essential Thoreau. More than twenty of Thoreau’s journal notebooks are shown along with letters and manuscripts, books from his library, pressed plants from his herbarium, and important personal artifacts. -

Self Guided Historical Walking Tour of Downtown Williamsport One Mile, Approximately 30 Minutes

Williamsport, Pennsylvania www.williamsportarts.com Self Guided Historical Walking Tour of Downtown Williamsport One mile, approximately 30 minutes. Begin at the Visitors Information Center off William St. west of the Hampton Inn. Until urban renewal in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the area to the east of the Visitors Information Center was known as Little Italy because most of its inhabitants and storekeepers were Italian immigrants and their descendants. Go north on William Street to the intersection of William and Third Streets. On the northwest corner is site #1. 1. The Grit Building, 200-222 West Third Street (1892) The Grit began in 1882 as a Saturday afternoon supplement to the Daily Sun and Banner. Printer Dietrick Lamade bought out his partner in 1884 and turned the Grit into an independent Sunday newspaper that grew to become known as “American’s greatest family newspaper.” Avoiding the “yellow journalism” of post-Civil War newspapers and instead, catering to the rising Victorian middle class, the newspaper focused on the goals and values of a family-oriented audience. The paper remained in the Lamade family until it was sold and relocated to Topeka, Kansas, in 1992. The original building on the corner was renovated for re-use. With its rounded arches, deep window and door reveals, and contrasting bands of colors, the building’s façade refl ects the uniquely American Romanesque Revival style of architect H.H. Richardson (1838-1886) 2. The Old Jail, 154 West Third Street (1868) On the northeast corner stands the second Lycoming County Jail, built after fi re destroyed the original structure that has served the county since 1799. -

The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 6-21-2018 The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected] Mary Sarah Bilder Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Profession Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Laurel Davis and Mary Sarah Bilder. "The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist." (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Library of Robert Morris, Antebellum Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist∗ Laurel Davis** and Mary Sarah Bilder*** Contact information: Boston College Law Library Attn: Laurel Davis 885 Centre St. Newton, MA 02459 Abstract (50 words or less): This article analyzes the Robert Morris library, the only known extant, antebellum African American-owned library. The seventy-five titles, including two unique pamphlet compilations, reveal Morris’s intellectual commitment to full citizenship, equality, and participation for people of color. The library also demonstrates the importance of book and pamphlet publication as means of community building among antebellum civil rights activists. -

Program Guide April 12-13, 2014 = Asheville, N.C

MOREMORE THTHANAN 1515 0 0 WORKSHOPS!WORKSHOPS! PP.. 88 EECCO-FRIEO-FRIENNDLYDLY MMAARKETPLRKETPLACACEE PP.. 2727 OFF-STOFF-STAAGEGE DDEMOEMONNSTRSTRAATIOTIONNSS PP.. 2222 KEYKEYNNOTEOTE SPESPEAAKERSKERS PP.. 77 PROGRAM GUIDE APRIL 12-13, 2014 = ASHEVILLE, N.C. 2 www.MotherEarthNewsFair.com Booths 2419, 2420, 2519 & 2520 DISCOVER The Home of Tomorrow, Today Presented by Steve Linton President, Deltec Homes Renewable Energy Stage Check Fair schedule for details LEARN Deltec Homes Workshop Presented by Joe Schlenk Director of Marketing, Deltec Homes Davis Conference Room Check Fair schedule for details ENGAGE Tour our plant on Friday, April 11 Deltec Homes RSVP 800.642.2508 Ext 801 deltechomes.com 69 Bingham Rd Asheville Visit our Model Home in Mars Hill, NC Tel 800.642.2508 Thursday, Friday & Saturday, 10 am - 5 pm 828-253-0483 MOTHER EARTH NEWS FAIR 3 omes, H e are particularlye are Grit l W Motorcycle Classics Motorcycle l eader R ept. 12-14, 2014 S Utne Utne l ourles. They represent some of the mostrepresent ourles. They esort, ct. 25-26, 2014 T R M-7:00 PM O M-5:00 PM A A Gas Engine Magazine Magazine Engine Gas l tephanie S nimal Nutrition and Yanmar. Yanmar. and nimal Nutrition A Mother Earth Earth Mother tate Fairgrounds, May 31-June 1, 2014 31-June May tate Fairgrounds, S hours: 9:00 Mother Earth Earth Mother hours: 9:00 Mother Earth News News Earth Mother prings Mountain prings Mountain S alatin and Fair Mother Earth Living Mother l Fair S even even ashington S FAIR HOURS FAIR Capper’s Farmer Farmer Capper’s l unday W aturday aturday S S around the country. -

Personality, Grit and Sporting Achievement

IOSR Journal of Sports and Physical Education (IOSR-JSPE) e-ISSN: 2347-6737, p-ISSN: 2347-6745, Volume 3, Issue 1 (Jan. – Feb. 2016), PP 14-17 www.iosrjournals.org Personality, Grit and Sporting Achievement Adeboye Israel Elumaro Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba – Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract: The role of personality traits in sporting achievement has generated interests among sport researchers and practitioners, however, studies on the relationship between sporting achievement and personality traits have yielded no clear evidence of a cause - effect relationship. Instead, psychological skills and attitudes have shown evidence of influence over sporting achievement. This study explored the possibility that grit, which is a behavioural element, would be more related to sporting achievement than personality traits. In total, 142 sport men & women (Mean age = 24.7 S= 3.5) completed the Grit Scale (Duckworth, Matthews & Kelly 2007) and the BFI-10 (Rammstedt& John, 2007), the level at which participant play in their sports was used as a measure of achievement. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed that Grit was a predictor of sporting achievement while personality traits showed no significant differences. The result also indicated that age differences may affect the levels of Extraversion, Conscientiousness, and Agreeableness of the Big Five Personality traits as well as the Ambition sub-scale of the Grit scale. Keywords: Sporting achievement, Personality traits, Grit, BFI-10, Multivariate analysis of variance I. Introduction Efforts to unearth the factors that underpin sporting achievement have been focused on linking personality traits to sporting success from the early years of sport psychology (Raglin, 2001). -

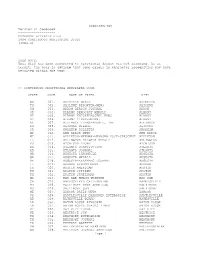

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

What Grades and Achievement Tests Measure

IZA DP No. 10356 What Grades and Achievement Tests Measure Lex Borghans Bart H.H. Golsteyn James J. Heckman John Eric Humphries November 2016 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor What Grades and Achievement Tests Measure Lex Borghans Maastricht University and IZA Bart H.H. Golsteyn Maastricht University and IZA James J. Heckman University of Chicago, American Bar Foundation and IZA John Eric Humphries University of Chicago Discussion Paper No. 10356 November 2016 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion.