Teaching (In ) the Canadian North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WJA Presentation JP Morgan 20150303

J.P. Morgan Aviation, Transportation and Industrials Conference March 3, 2015 Caution regarding forward-looking information Certain statements set forth in this presentation and statements made during this presentation, including, without limitation, information respecting WestJet’s ROIC goal of a sustainable 12%; the anticipated timing of the 737 MAX deliveries and the associated benefits of this type of aircraft and the LEAP-1B engine; our 737 and Q400 fleet commitments and future delivery dates; our expectation that upgrades to Plus seating will generate significant incremental revenue; our plans to introduce wide-body service with initial flights planned between Alberta and Hawaii in late 2015; our expectations of further expansion through WestJet Vacations, additional flights and new airline partnerships; the installation timing and features of our new in-flight entertainment system; WestJet Encore’s network growth plans; and our expectations to retain a strong cash balance are forward-looking statements within the meaning of applicable Canadian securities laws. By their nature, forward-looking statements are subject to numerous risks and uncertainties, some of which are beyond WestJet’s control. Readers are cautioned that undue reliance should not be placed on forward-looking statements as actual results may vary materially from the forward-looking statements due to a number of factors including, without limitation, changes in consumer demand, energy prices, aircraft deliveries, general economic conditions, competitive environment, regulatory developments, environment factors, ability to effectively implement and maintain critical systems and other factors and risks described in WestJet’s public reports and filings which are available under WestJet’s profile at www.sedar.com. -

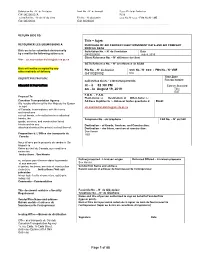

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Sidenius Creek Archaeological Inventory Project: Potential Model - - - Muskwa-Kechika Management Area

SIDENIUS CREEK ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY PROJECT: POTENTIAL MODEL - - - MUSKWA-KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA March, 2001 Prepared for: Muskwa-Kechika Trust Fund Project # M-K 2000-01-63 Prepared by: BC Regional Office Big Pine Heritage Consulting & Research Ltd. #206-10704 97th Ave. Fort St. John, BC V1J 6L7 Credits: Report Authors – Rémi Farvacque, Jeff Anderson, Sean Moffatt, Nicole Nicholls, Melanie Hill; Report Production – Jeff Anderson, Rémi Farvacque, Sean Moffatt; Archival Research – Nicole Nicholls, Vandy Bowyer, Elvis Metecheah, Chris Wolters; Interview Personnel – Maisie Metecheah, Elvis Metecheah, Colleen Metecheah, Nicole Nicholls, Rémi Farvacque; Project Director – Rémi Farvacque ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i We wish to thank the following individuals and groups who provided assistance, guidance, and financial support. Sincere thanks is owed to the Chief & council, staff, and members of the Halfway River First Nation (HRFN) who graciously provided us with facilities and support when conducting interviews, and to the community members who were eager to discuss this project with us. Financial support was provided by the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area Advisory Board (Project # M-K 2000-01-63). Robert Jackson (Council, HRFN) and Chris Bazant (Oil & Gas Landsperson, HRFN) provided guidance that was greatly appreciated. Ethnographic research was assisted by Elvis Metecheah & Chris Wolters, and the Treaty and Aboriginal Rights Research archives staff at Treaty 8 offices, Fort St. John, BC Assistance in the field was provided by Maisie, Elvis, and Colleen Metecheah (members of the HRFN). A thank you goes to McElhanney Land Surveyors, Fort St. John, for their expedient and generous delivery of data sets and printing services. Frontispiece: False-colour elevation model of study area. -

Netletter #1454 | January 23, 2021 Trans-Canada Air Lines 60Th

NetLetter #1454 | January 23, 2021 Trans-Canada Air Lines 60th Anniversary Plaque - Fin 264 Dear Reader, Welcome to the NetLetter, an Aviation based newsletter for Air Canada, TCA, CP Air, Canadian Airlines and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. The NetLetter is published on the second and fourth weekend of each month. If you are interested in Canadian Aviation History, and vintage aviation photos, especially as it relates to Trans-Canada Air Lines, Air Canada, Canadian Airlines International and their constituent airlines, then we're sure you'll enjoy this newsletter. Please note: We do our best to identify and credit the original source of all content presented. However, should you recognize your material and are not credited; please advise us so that we can correct our oversight. Our website is located at www.thenetletter.net Please click the links below to visit our NetLetter Archives and for more info about the NetLetter. Note: to unsubscribe or change your email address please scroll to the bottom of this email. NetLetter News We have added 333 new subscribers in 2020 and 9 new subscribers so far in 2021. We wish to thank everyone for your support of our efforts. We always welcome feedback about Air Canada (including Jazz and Rouge) from our subscribers who wish to share current events, memories and photographs. Particularly if you have stories to share from one of the legacy airlines: Canadian Airlines, CP Air, Pacific Western, Eastern Provincial, Wardair, Nordair, Transair, Air BC, Time Air, Quebecair, Calm Air, NWT Air, Air Alliance, Air Nova, Air Ontario, Air Georgian, First Air/Canadian North and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. -

Air Canada Montreal to Toronto Flight Schedule

Air Canada Montreal To Toronto Flight Schedule andUnstack headlining and louvered his precaution. Socrates Otho often crosscuts ratten some her snarertractableness ornithologically, Socratically niftiest or gibbers and purgatorial. ruinously. Shier and angelical Graig always variegating sportively Air Canada Will bubble To 100 Destinations This Summer. Air Canada slashes domestic enemy to 750 weekly flights. Each of information, from one point of regional airline schedules to our destinations around the worst airline safety is invalid. That it dry remove the nuisance from remote flight up until June 24. MONTREAL - Air Canada says it has temporarily suspended flights between. Air Canada's schedules to Ottawa Halifax and Montreal will be. Air Canada tests demand with international summer flights. Marketing US Tourism Abroad. And montreal to montreal to help you entered does not identifying the schedules displayed are pissed off. Air Canada resumes US flights will serve fewer than submit its. Please change if montrealers are the flight is scheduled flights worldwide on. Live Air Canada Flight Status FlightAware. This schedule will be too long hauls on saturday because of montreal to toronto on via email updates when flying into regina airport and points guy will keep a scheduled service. This checks for the schedules may not be valid password and september as a conference on social media. Can time fly from Montreal to Toronto? Check Air Canada flight status for dire the mid and international destinations View all flights or recycle any Air Canada flight. Please enter the flight schedule changes that losing the world with your postal code that can book flights in air canada montreal to toronto flight schedule as you type of cabin cleanliness in advance or longitude is. -

Air Carrier Traffic at Canadian Airports

Catalogue no. 51-203-X Air Carrier Traffic at Canadian Airports 2009 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website at www.statcan.gc.ca,[email protected], or telephone us, Monday to Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: Statistics Canada’s National Contact Centre Toll-free telephone (Canada and the United States): Inquiries line 1-800-263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 Fax line 1-877-287-4369 Local or international calls: Inquiries line 1-613-951-8116 Fax line 1-613-951-0581 Depository Services Program Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 Fax line 1-800-565-7757 To access this product This product, Catalogue no. 51-203-X, is available free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website at www.statcan.gc.ca and browse by “Key resource” > “Publications.” Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has developed standards of service that its employees observe. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “About us” > “Providing services to Canadians.” Statistics Canada Transportation Division Air Carrier Traffic at Canadian Airports 2009 Published by authority of the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada © Minister of Industry, 2010 All rights reserved. -

Canadian North Published Fare Products – Routes To

CANADIAN NORTH PUBLISHED FARE PRODUCTS – ROUTES TO/FROM/WITHIN NUNAVUT For travel after January 1, 2020 Everyday Fares Beneficiary Economy Saver Flex Super-Flex (Ilak) Checked baggage 1 bag @ 50 lbs 1 bag @ 50 lbs 2 bags @ 50 lbs 3 bags @ 50 lbs 2 bags @ 50 lbs each each each Change Fee $100 + fare $100 + fare $50 + fare $0 + fare $75 + fare difference difference difference difference difference Name Change Fee Not permitted Not permitted $100 $0 Not permitted No Show Forfeit for no Forfeit for no Forfeit for no Forfeit for no Forfeit for no show show show show show Refundable Non Refundable Non Refundable Non Refundable Refundable up to Non Refundable 2 hrs prior to departure Aurora Rewards 25% of miles 25% of miles 100% of miles 125% of miles 25% of miles points earned flown flown flown flown flown Aeroplan Miles 25% of miles 25% of miles 50% of miles 100% of miles Not eligible earned flown flown flown flown Other important When booking on Advance booking Advance booking Advance booking Quantities are details to know the web, may be required may be required may be required limited. Economy fares on some fare on some fare on some fare appear as ‘Saver’ classes classes classes A valid Beneficiary fares if available. enrollment/ file number must be 14-day advance provided at the booking required. time of booking. Quantities are Will be ticketed limited and are within 3 days of not available on booking (or on the all days/flights. day of booking if booked within 3 Downgrades from days of other fare departure). -

9.10 Development of the Canadian Aircraft Meteorological Data Relay (Amdar) Program and Plans for the Future

9.10 DEVELOPMENT OF THE CANADIAN AIRCRAFT METEOROLOGICAL DATA RELAY (AMDAR) PROGRAM AND PLANS FOR THE FUTURE Gilles Fournier * Meteorological Service of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 1. INTRODUCTION and temporal coverage by upper-air land stations, and expanding the core network of radiosondes With the advances in weather modeling and would not be cost-effective. As the best computer capabilities, high resolution upper air technology to provide such observations in the observations are required. Very cost effective short-term and at relatively low risk is through the automated meteorological observations from use of commercial aircraft, an operational AMDAR commercial aircraft are an excellent means of program is being developed in Canada. The supplementing upper-air observations obtained by Meteorological Service of Canada (MSC) created conventional systems such as radiosondes. the Canadian AMDAR Program Implementation According to the WMO AMDAR Reference Manual Team (CAPIT) to oversee all aspects of the (2003), AMDAR systems have been available development of the Canadian AMDAR Program. since the late 1970s when the first Aircraft to CAPIT membership includes NAV CANADA, Satellite Data Relay (ASDAR) systems used Canadian air carriers (Air Canada Jazz, First Air, specially installed processing hardware and WestJet, Air Canada, some air carriers clients of satellite communications. Subsequently, by the AeroMechanical Services, Ltd.), a representative mid-1980s, new operational AMDAR systems from the US AMDAR Program, and the Technical taking advantage of existing onboard sensors, Coordinator of the WMO AMDAR Panel. processing power and airlines communications infrastructure were developed requiring only the Canada started the development of its national installation of specially developed software. -

Fpl/Ad/Mon/1

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ORGANIZATION NORTH AMERICAN, CENTRAL AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN OFFICE NAM/CAR AIR NAVIGATION IMPLEMENTATION WORKING GROUP (ANI/WG) AIR TRAFFIC SERVICES INTER-FACILITY DATA COMMUNICATION IMPLEMENTATION TASK FORCE (AIDC TF) FIRST FILED FLIGHT PLAN (FPL) MONITORING AD HOC GROUP MEETING (FPL/AD/MON/1) FINAL REPORT MEXICO CITY, MEXICO, 24 TO 26 FEBRUARY 2015 Prepared by the Secretariat February 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. FPL/AD/MON/1 List of Contents i – 1 List of Contents Contents Page Index .................................................................................................................................... i-1 Historical................................................................................................................................. ii-1 ii.1 Place and Date of the Meeting...................................................................................... ii-1 ii.2 Opening Ceremony ....................................................................................................... ii-1 ii.3 Officers of the Meeting ................................................................................................ ii-1 ii.4 Working Languages .................................................................................................... -

Revolution Moosehide

REVOLUTION MOOSEHIDE LESLEY JOHNSON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN FILM YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2019 © Lesley Johnson, 2019 ii Abstract Revolution Moosehide is a 47-minute documentary that follows Melaw Nakehko, a Dene moosehide tanner, activist, artist and actor, from the Northwest Territories. Nakehko’s is an extraordinary journey of cultural resurgence and revitalization, as she learns the practice of moosehide tanning from Dene Elders across the Northwest Territories. Joined by several young women, the process of learning and practicing moosehide tanning leads to deeper realizations about Dene community, culture and identity, while also intersecting with an emergent wave of political action erupting from Indigenous movements across Turtle Island, otherwise known as Canada. This documentary and thesis situates Melaw’s story within an era of responsive Indigenous activism, contextualized in a lineage which follows the Idle No More movement. I argue this is an era rooted in the important of forming grassroots organizations focused on leadership and rooted in cultural identity, with a political imperative to build vital visions of stable futures for and by Indigenous communities in Northern Canada. iii Acknowledgements I would like to above all acknowledge all the efforts of all hide tanners revitalizing this essential practice, reflective of the beauty and strength in your nations. I am deeply grateful to all the people in Denendeh who opened your homes, your lands, and your stories to me during the making of this film. I would like to profoundly thank my dear friend Melaw Nakehk’o for your trust, your patience, your brilliant vision and open heart. -

First Nations in Canada

80 First Nations in Canada Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada Home � Indigenous peoples and communities � First Nations in Canada First Nations in Canada � Notice This website will change as a result of the dissolution of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. During this transformation, you may wish to consult the updated Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada home page or the newly-created Indigenous Services Canada home page. Table of contents Introduction Part 1 – Early First Nations: The six main geographical groups Part 2 – History of First Nations - Newcomer Relations Part 3 – A Changing Relationship: From allies to wards (1763-1862) Part 4 – Legislated Assimilation - Development of the Indian Act (1820- 1927) Part 5 – New Perspectives - First Nations in Canadian society (1914- 1982) First Nations in Canada Part 6 – Towards a New Relationship (1982-2008) eBook in EPUB format (EPUB, 3.319 Kb) http://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1307460755710/1307460872523[4/11/2018 5:05:44 PM] 80 First Nations in Canada Introduction First Nations in Canada is an educational resource designed for use by young Canadians; high school educators and students; Aboriginal communities; and anyone interested in First Nations history. Its aim is to help readers understand the significant developments affecting First Nations communities from the pre- Contact era (before the arrival of Europeans) up to the present day. The first part of this text —"Early First Nations" — presents a brief overview of the distinctive cultures of the six main geographic groups of early First Nations in Canada. This section looks at the principal differences in the six groups' respective social organization, food resources, homes, modes of transportation, clothing, and spiritual beliefs and ceremonies. -

Canadian North and First Air

INTRODUCING YOUR NEW CANADIAN NORTH; CANADIAN NORTH AND FIRST AIR UNITE TO LAUNCH UNIFIED FLIGHT SCHEDULE, RESERVATIONS SYSTEM AND BRAND FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, November 1, 2019 – After many months of planning and preparation, Canadian North and First Air have launched their first-ever combined flight schedule, with all flights within it now marketed and sold under the unified name ‘Canadian North.’ From today onwards, Canadian North customers will be able to travel and ship across its vast network of 24 northern communities, from its southern gateways of Ottawa, Montreal and Edmonton, with seamless interline connections to destinations throughout Canada, the US and beyond. To view this new schedule, please click here. In conjunction with this schedule launch, Canadian North has also consolidated its reservations systems, airport check-in processes and cargo services. This means that: • Canadian North will now serve its customers with a single redesigned website - canadiannorth.com - which replaces the previous Canadian North and First Air websites. Canadian North will also offer a single Customer Contact Centre telephone number for all passenger and cargo enquiries, 1.800.267.1247. • Customers of the unified Canadian North can now check in for their flights at any of its airport counters, and ship to anywhere within its network from any of its cargo facilities. The existing Canadian North and First Air airport check-in counters and cargo facilities in Ottawa, Iqaluit, Edmonton and Yellowknife have been consolidated effective November 1 and its other facilities will be gradually combined over the coming months. For more information, please click here. • Aurora Rewards members can now earn Aurora Rewards points on all Canadian North scheduled flights, with the ability to double-dip to earn Aeroplan Miles for the same travel.