ON HUMAN PRESENCE INSIDE the REPRESENTATION SPACE of the PAINT BRUSH Aurora Corominas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Dreams May Come St

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College St. Norbert College Magazine 2007-2012 St. Norbert College Magazine Fall 2012 Fall 2012: What Dreams May Come St. Norbert College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/snc_magazine_archives Recommended Citation St. Norbert College, "Fall 2012: What Dreams May Come" (2012). St. Norbert College Magazine 2007-2012. 1. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/snc_magazine_archives/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Norbert College Magazine at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Norbert College Magazine 2007-2012 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. fall 2012 volume 44 number 3 What Dreams May Come Seizing the bright years ahead PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2011-12 St. NorBert CollEGe MaGaZine G ueS t E d itoR iaL The dream collective Drew Van Fossen Director of Communications and Design While I was thinking about this column, I bounced a few ideas off my son Joel. Joel is a St. Norbert senior majoring in philosophy and, when I told him I wanted What Dreams May Come to write about how we realize our dreams, his immediate reply was that the best of dreams are virtuous dreams. 7 Momentum Shifts Gears to Full Ahead: A comprehensive campaign for St. Norbert In his estimation, when our dreams are too much about us – too self-centered Reflecting the mission statement of the college, 10 Big dreams: Members of the Class of 2016 share their aspirations – they are also too specific, and inevitably fall short and disappoint. -

10 MISTAKES People Make About HEAVEN HELL and the AFTERLIFE MIKE FABAREZ MIKE FABAREZ

101010 MISTAKES People Make About HEAVEN HELL AND THE AFTERLIFE MIKE FABAREZ MIKE FABAREZ Copyrighted material 10 Mistakes People Make About Heaven, Hell, and the Afterlife.indd 1 5/7/18 8:06 AM All Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permis- sion. All rights reserved. Cover by Brian Bobel Design, Whites Creek, TN Cover photos © LeArchitecto / iStockphoto 10 Mistakes People Make About Heaven, Hell, and the Afterlife Copyright © 2018 Mike Fabarez Published by Harvest House Publishers Eugene, Oregon 97408 www.harvesthousepublishers.com ISBN 978-0-7369-7301-4 (pbk.) ISBN 978-0-7369-7302-1 (eBook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Fabarez, Michael, 1964- author. Title: 10 mistakes people make about heaven, hell, and the afterlife / Mike Fabarez. Other titles: Ten mistakes people make about heaven, hell, and the afterlife Description: Eugene, Oregon : Harvest House Publishers, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2018000689 (print) | LCCN 2018006024 (ebook) | ISBN 9780736973021 (ebook) | ISBN 9780736973014 (pbk.) Subjects: LCSH: Future life— Christianity. | Heaven— Christianity. | Hell— Christianity. Classification: LCC BT903 (ebook) | LCC BT903 .F33 2018 (print) | DDC 236/.2— dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018000689 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 / BP-SK / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Copyrighted material Contents What Lies Beyond the Grave? ...................... -

Nightmares of Eminent Persons

NIGHTMARES OF EMINENT PERSONS AND OTHER STORIES BY BERTRAND RUSSELL The Impact of Science on Society New Hopes for a Changing World Authority and the Individual Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits History of Western Philosophy The Principles of Mathematics Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy The Analysis of Mind Our Knowledge of the External World An Outline of Philosophy The Philosophy of Leibniz An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth Unpopular Essays Power In Praise of Idleness The Conquest of Happiness Sceptical Essays Mysticism and Logic The Scientific Outlook Marriage and Morals Education and the Social Order On Education Freedom and Organization, 1814-1914 Principles of Social Reconstruction Roads to Freedom Practice and Theory of Bolshevism Satan in the Suburbs NIGHTMARES OF EMINENT PERSONS AND OTHER STORIES by BERTRAND RUSSELL illustrated by CHARLES W. STEWART THE BODLEY HEAD LONDON First published 1954 Reprinted 1954 by arrangement with the author's regular publishers GEORGE ALLEN AND UNWIN LTD This look is copyright under the Berne Convention. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study y research^ criticism or review^ as permitted under the Copyright Act 1911, no portion may be reproduced by any process without n. Inquiry should be made to the publisher. Printed in Great Britain by UNWIN BROTHERS LIMITED, WOKING AND LONDON for JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD LTD 28 Little Russell Street London WCi PREFACE It is only fair to warn the reader that not all the stories in this volume are intended to cause amusement. Of the "Night- mares," some are purely fantastic, while others represent possible, though not probable, horrors. -

AITKEN Leonard Thesis

Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth- Century Art. c. Leonard Aitken 2014 Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth- Century Art. SUBMISSION OF THESIS TO CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY: Degree of Master of Arts (Honours) CANDIDATE’S NAME: Leonard Aitken QUALIFICATIONS HELD: Degree of Master of Arts Practice (Visual Arts), Charles Sturt University, 2011 Degree of Bachelor of Arts (Visual Arts), Charles Sturt University, 1995 FULL TITLE OF THESIS: Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth-Century Art. MONTH AND YEAR OF SUBMISSION: June 2014 Time Unbound: An Exploration of Eternity in Twentieth- Century Art. SUBMISSION OF THESIS TO CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY: Degree of Master of Arts (Honours) ABSTRACT The thesis examines contemporary works of art which seek to illuminate, describe or explore the concept of ‘eternity’ in a modern context. Eternity is an ongoing theme in art history, particularly from Christian perspectives. Through an analysis of artworks which regard eternity with intellectual and spiritual integrity, this thesis will explain how the interpretation of ‘eternity’ in visual art of the twentieth century has been shaped. It reviews how Christian art has been situated in visual culture, considers its future directions, and argues that recent forms are expanding our conception of this enigmatic topic. In order to establish how eternity has been addressed as a theme in art history, the thesis will consider how Christian art has found a place in Western visual culture and how diverse influences have moulded the interpretation of eternity. An outline of a general cosmology of eternity will be treated and compared to the character of time in the material world. -

What Dreams May Come? the Most Famous Soliloquy in Literature Is

What Dreams May Come? Page 1 of 3 What Dreams May Come? The most famous soliloquy in literature is probably Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” speech. He is contemplating death and if this cessation of temporal life this side of the grave described as “a sea of troubles” bring to pass sweet dreams or nightmares. Here are Shakespeare’s words from Hamlet, “To die, to sleep – to sleep, perchance to dream. Ah, there’s the rub, for in that sleep of death what dreams may come….” Here Hamlet contemplates dreams that await us in “the undiscovered country…” In August 9 Newsweek’s article, The Mystery of Dreams , Barbara Kantrowitz and Karen Springden say “… it’s (researching our dreams) the closest we’ve come to recording the soul,” Rosalind Cartwright, a chairman of psychology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago says, “If you’re going to understand human behavior, here’s a big piece of it. Dreaming is our own storytelling time- to help us know who we are, where we’re going and how we’re going to get there.” In the Book of Acts God repeats a promise from Joel concerning the last days, "And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams" (Acts 2:17). God has a lot to say about dreams. You will find sixty-one verses that mention “dream,” twenty-one verses that mention the plural form “dreams,” four verses that mention “dreamers,” seventeen verses using the word “dreamed,” seventy-three usages of “vision,” and twenty-four times “visions” is mentioned. -

Apocalypse Now? Towards a Cinematic Realized Eschatology

Apocalypse Now? Towards a Cinematic Realized Eschatology Christopher Deacy Introduction Although the last century has, arguably, “generated more eschatological discussion than any other”1, Andrew Chester makes the instructive point that – paradoxical though it may seem to be – there has been a relative scarcity of eschatological thinking within Christian theology. Chester’s thinking, here, is that, from the Patristic period onward, eschatology was never as fully developed, profoundly reflected upon, or given as rigorous and imaginative intellectual probing, as were such other areas of Christian theology as Christology (Christian doctrine about the person of Christ) and soteriology. The specific context of Chester’s argument does not revolve around debates in the field of theology and film, but there is an important sense in which what he is arguing in his article finds a certain resonance in film and theology circles. When he writes that “There is still a need for a rigorous and intellectually sustainable account of Christian eschatology”2, the case could equally be made that when filmmakers draw on traditional images and representations of eschatology in their works – and there is little doubt that themes of death and the afterlife comprise perennial themes in cinema, as evinced by the likes of A Matter of Life and Death (Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, 1945), Heaven Can Wait (Warren Beatty & Buck Henry, 1978), Made in Heaven (Alan Rudolph, 1987), Ghost (Jerry Zucker, 1990), Defending Your Life (Albert Brooks, 1991) and What Dreams -

4Th Age Film List

Curriculum for the 4th Age Film List Title DVD Comments date when owned by watched The Death and Life of Charlie St. Cloud CCC Between Love and Promise to look after brother 17/1/15 Driving Miss Daisy Ageing, Friendship 16/3/13 Goodnight Mister Tom Deep Friendship Old Man – Young Boy 1/2/14 Hannah Hauxwell True Story; Hard Life - Letting Go - Travelling 1st Time 30/3/13 Harold and Maude CCC Love between old woman and young man 13/4/13 20/12/14 Little Big Man CCC Old Man's Western Epic with Dustin Hoffman 23/11/13 On Golden Pond CCC Family Relationships, esp. Grandfather –son 27/4/14 The Iron Lady Life/Aging of M. Thatcher , dementia 13/4/13 Untouchables 4th Age after Accident, Friendship Hall Feb 13 Mrs Caldicot's Cabbage War CCC nursing home 24/5/14 Amour CCC couple facing debilitating stroke and death Hall April 13 Departures CCC funerals 26/10/13 Marigold Hotel CCC Ageing, new beginnings Hall 2012 18/11/14 CC Cocoon CCC old age, housing 8/11/14 The Notebook CCC dementia 9/11/13 My Mother Frank empty nest, early onset dementia 2/3/13 Meet Joe Black CCC death Oct 13 The Bucket List CCC time to start living June 13 The Secret Life of Bees CCC trauma, healing, racism July 13 The Quartett CCC nursing home 7/12/13 Fierce Grace CCC stroke, Ram Dass 5/10/13 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button CCC ageing, nursing home 21/12/13 When did you last see your father CCC dying, life review, father – son 4/1/14 Enlightenment Guaranteed Buddhism 10/5/14 Mo CCC Mo Mowlam, cancer, Northern Ireland 12/4/14 Lost for Words CCC stroke 29/3/14 Calendar Girls -

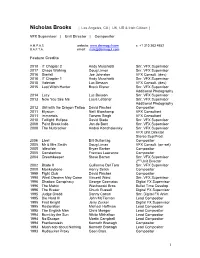

1 Feature Credits

Nicholas Brooks | Los Angeles, CA | UK, US & Irish Citizen | VFX Supervisor | Unit Director | Compositor A.M.P.A.S. website: www.darmogul.com c: +1 310 383 4852 B.A.F.T.A. email: [email protected] Feature Credits 2018 IT Chapter 2 Andy Muschietti Snr. VFX Supervisor 2017 Chaos Walking Doug Limon Snr. VFX Supervisor 2016 Starfall Joe Johnston VFX Consult. (dev) 2016 IT Chapter 1 Andy Muschietti Snr. VFX Supervisor 2015 Valerian Luc Besson VFX Consult. (dev) 2015 Last Witch Hunter Breck Eisner Snr. VFX Supervisor Additional Photography 2014 Lucy Luc Besson Snr. VFX Supervisor 2013 Now You See Me Louis Letterier Snr. VFX Supervisor Additional Photography 2012 Girl with the Dragon Tattoo David Fincher Compositor 2011 Elysium Neill Blomkamp VFX Consultant 2011 Immortals Tarsem Singh VFX Consultant 2010 Twilight: Eclipse David Slade Snr. VFX Supervisor 2009 Point Break Indo Jan de Bont Snr. VFX Supervisor 2008 The Nutcracker Andrei Konchalovsky Snr. VFX Supervisor VFX Unit Director Stereo Sup/Prod. 2006 Live! Bill Guttentag Compositor 2005 Mr & Mrs Smith Doug Liman VFX Consult. (on-set) 2005 Idlewilde Bryan Barber Compositor 2005 Constantine Frances Lawrance Compositor 2004 Dreamkeeper Steve Barron Snr. VFX Supervisor 2nd Unit Director 2002 Blade II Guillermo Del Toro Snr. VFX Supervisor 2000 Monkeybone Henry Selick Compositor 1999 Fight Club David Fincher Compositor 1998 What Dreams May Come Vincent Ward Snr. VFX Supervisor 1996 Shadow Conspiracy George Cosmatoc Digital FX Supervisor 1996 The Matrix Wachowski Bros. Bullet Time Develop. 1996 The Eraser Chuck Russell Digital FX Supervisor 1995 Judge Dredd Danny Canon Snr. Digital FX Anim. -

Adaptations of Dante's Commedia in Popular American Fiction and Film

ঃਆઽࢂٷணপ࠙ 제17권 2호 (2009): 197-212 Adaptations of Dante’s Commedia in Popular American Fiction and Film Philip Edward Phillips (Middle Tennessee State University) The punishments reflect the sins in Dante Alighieri’s Commedia. Indeed, drawing upon Augustinian and Thomistic theology, Dante creates punishments in the circles of the Commedia that hauntingly reveal to the reader the nature of each sin and the damned condition of each class of sinner. Dante identifies the logical relationship between sin and its punishment in the Commedia as “contrapasso,” or “counterpoise,” as translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his 1867 translation of the Inferno. The concept of “counterpoise” is related to the Old Testament notion of exacting “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” but it is far more complex notion. Dante uses the troubadour poet, Bertrand de Born (ca. 1140-ca.1215), who was responsible for encouraging discord between King Henry II of England and his son, the young Prince Henry, as the defining 198 Philip Edward Phillips example of “counterpoise” in the Inferno, Circle 8, Bolgia 9. The pilgrim Dante says to his guide, the great Roman epic poet, Virgil: I truly saw, and still I seem to see it, A trunk without a head walk in like manner As walked the others in the mournful herd. And by the hair of it held the head dissevered, Hung from the hand in the fashion of a lantern, And that upon us gazed and said: “O me!” It of itself made to itself a lamp, And they were two in one, and one in two; How that can be, He knows who so ordains it. -

Movies About Grief Rabbit Hole – Nicole Kidman

Movies About Grief Rabbit Hole – Nicole Kidman Grief in the Family – What happens after the unthinkable happens? Rabbit Hole, based on the Tony- winning play by David Lindsay-Abaire and deftly directed by John Cameron Mitchell, slowly reveals the answer: something else unthinkable. Rabbit Hole is a moving, dark character study of what happens to a happily married couple, Becca and Howie (Nicole Kidman and Aaron Eckhart), who suddenly lose the love of their life, their 4-year-old son. As in real life, the grief portrayed in Rabbit Hole takes peculiar twists and turns, and the deep sorrow and tragedy of the story is leavened by dark humor–much of it coming from Kidman. While Rabbit Hole is not an upbeat film, it’s emotionally resonant in the ways of some of the best films on similar subjects–like Ordinary People, Revolutionary Road, and In the Bedroom. Purchase This Movie at Amazon.com Taking Chance – Kevin Bacon Military Grief – Based on the true experiences of Lt. Colonel Michael Strobl, who wrote eloquently of them in a widely circulated 2004 article, Taking Chance is a profoundly emotional look at the military rituals taken to honor its war dead, as represented by a fallen Marine killed in Iraq, Lance Corporal Chance Phelps. Working as a strategic analyst at Marine Corps Base Quantico in VA, Lt. Col. Strobl (Kevin Bacon) learns that Phelps had once lived in his hometown, and volunteers to escort the body to its final resting place in Wyoming. As Strobl journeys across America, he discovers the great diligence and dignity in how the military, and all those involved with preparing and transporting the body, handle their duties. -

By JIMI BERNATH

BARDO FILMS CINEMA OF THE AFTERLIFE by JIMI BERNATH 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction “Carnival of Souls” : Familiar Nightmares …………………………………………………..………...43 Bardo Blockbusters : “American Beauty” & “The Sixth Sense” ……………….……...…..85 “Jacob’s Ladder” : Search for a Guide ……………………………………………………..………….102 “Enter the Void” : Escape Velocity …………………………………………………………..…………. 49 The Dharma of Lynch: “Mulholland Drive” & “Inland Empire” ……………….……….108 “Vera” : The Underworld ………………………………………………………………………..…...……….106 Escape from Hell : “Diamonds of the Night” …………………………………………….………. 26 “Le Quattro Volte” : Elemental Change ……………………………………………………..…………..7 “Beetlejuice” : Guide as Huckster …………………………………………………………….…………..78 “Defending Your Life” : Purgatory as Shtick …………………………………………….…………90 “Ink” : Remembering Who You Were …………………………………………………………….…….59 “The Bothersome Man” : Not Bad As Purgatories Go …………………………….………….64 “The Lovely Bones” : Avenging Angel …………………………………………………………….….55 Following Robin : “Being Human” & “What Dreams May Come” …………………...22 Following Downey : “Chances Are” & “Hearts and Souls” ………………………………..46 Death at an Early Age : “Donnie Darko” & “Wristcutters a Love Story” ………….94 “Samaritan Girl” : Saint or Sinner ……………………………………………………………………..126 “The Life Before Her Eyes” : Headline Bardo ……………………………………………….…….75 Dia de Muertos : “Macario” “The Book of Life” & “Coco” …………………………..……..9 “Waking Life” : All Our Guides …………………………………………………………………….……...68 Japanese Ghost Stories : “Pitfall” & “Kuroneko” ……………………….…………….………..29 Crossing the Big -

Au Vepso Is a Sometime Literary Magazine

Au vepso is a sometime literary magazine. And V7hat, you ask, may that mean? For is not this "magazine," mimeographed and stapled as it is, with no table of contents, occasionally appearing at the vjhim of volunteer workers and obsessed romantics—obsessed by the idea that the hard finality of the printed creative work of St. John's students might enrich the conversation in some meaningful way—is not this "magazine" a work of sheer lunacy? It is indeed occasionally, sometimes, and never very successfully literate, but in the past this phrase "some time literary" has come mainly to mean the pretentious, the over blown, the Still-Idolized abortion. In the past the crisp sureness of AU verso's neatly typed pages has given an illusory permanence to works which should never have seen the light of day. We hope you will not find these vices in the present issue. Yet we wish to raise a most troubling question and one most important; this venture with aims and potentialities so high—to reflect, serve, and enrich the intellectual and artistic life of the college—is it possible that this venture be carried out by but a handful of deluded idealistic dreamers? All those who have been intimately connected with the demon bitch AU ITiRSO know this to be impossible. Every prior AU VERSO has implicitly pleaded for help; in this AU VERSO let us explicitly plead for your contributions, no matter how ill-formed and incomplete you think them to be, hoping that we find in you the absurd romanticism necessary for such a huge and thankless task.