Sequential Analysis of Livestock Herding Dog and Sheep Interactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

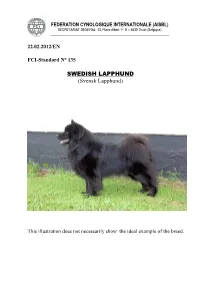

SWEDISH LAPPHUND (Svensk Lapphund)

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1 er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ 22.02.2012/EN FCI-Standard N° 135 SWEDISH LAPPHUND (Svensk Lapphund) This illustration does not necessarily show the ideal example of the breed. 2 TRANSLATION : Renée Sporre-Willes / Original version (En). ORIGIN : Sweden. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD : 10.11.2011. UTILIZATION : Reindeer herding dog, nowadays mainly kept as an all-round companion dog. FCI-CLASSIFICATION : Group 5 Spitz and primitive types. Section 3 Nordic Watchdogs and Herders. Without working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY : The Swedish Lapphund has been known in the Nordic area for centuries. It is a Nordic Spitz used in the past for reindeer herding, hunting and as a watchdog by the nomadic Laplanders. Nowadays it is mainly kept as a versatile companion dog. GENERAL APPEARANCE : Typical Spitz dog of slightly less than medium size and with proud head carriage IMPORTANT PROPORTIONS : Rectangular body shape. BEHAVIOUR / TEMPERAMENT : Lively, alert, kind and affectionate. The Lapphund is very receptive, attentive and willing to work. Its abilities as a good herding dog made it very useful in the reindeer trade. It is very versatile, suitable for obedience training, agility, herding, tracking, etc. It is easy to train, full of endurance and toughness. HEAD FCI-St. N° 135 / 22.02.2012 3 CRANIAL REGION: Skull: Slightly longer than broad; forehead rounded and occiput not clearly defined. Stop: Very well marked. FACIAL REGION: Nose: Preferably charcoal black , very dark or in harmony with coat colour. Muzzle: A little more than one third of the length of the head. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Sled Dogs in Our Environment| Possibilities and Implications | a Socio-Ecological Study

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1996 Sled dogs in our environment| Possibilities and implications | a socio-ecological study Arna Dan Isacsson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Isacsson, Arna Dan, "Sled dogs in our environment| Possibilities and implications | a socio-ecological study" (1996). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3581. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3581 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I i s Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University ofIVIONTANA. Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** / Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Date 13 ^ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. SLED DOGS IN OUR ENVIRONMENT Possibilities and Implications A Socio-ecological Study by Ama Dan Isacsson Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Studies The University of Montana 1996 A pproved by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School (2 - n-çç Date UMI Number: EP35506 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Livestock Guardian Dogs Tompkins Conservation Wildlife Bulletin Number 2, March 2017

LIVESTOCK GUARDIAN DOGS TOMPKINS CONSERVATION WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2, MARCH 2017 Livestock vs. Predators TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation PAGE 01 through the use of livestock guardian dogs Livestock vs. Predators: Introduction to an historical conflict and its mitigation through the use Since humans began domesti- stock and wild predators. Histor- of livestock guardian dogs cating animals, it has been nec- ically, humans have attempted PAGE 04 essary to protect livestock from to resolve this conflict through Livestock Guardian Dogs, wild predators. To this day, pre- a series of predator population an Ancient Tool in dation of livestock is one of the control measures including the Modern Times most prominent global hu- use of traps, hunting, and indis- PAGE 06 man-wildlife conflicts. Interest- criminate and nonselective poi- What Is the Job of a ingly, one of our most ancient soning—methods which are of- Livestock Guardian Dog? domestic companions, the dog, ten cruel and inefficient. was once a predator. One of the greatest chal- PAGE 07 The competition between lenges lies in successfully im- Breeds of Livestock man and wildlife for natural plementing effective measures Guardian Dogs spaces and resources is often that mitigate the negative im- PAGE 08 considered the main source of pacts of this conflict. It is imper- The Presence of Livestock conflict between domestic live- ative to ensure the protection of Guardian Dogs in Chile WILDLIFE BULLETIN NUMBER 2 MARCH 2017 man and his resources, includ- tion in predators is lower than PAGE 10 ing livestock, without compro- that of the United States, where Livestock in the Chacabuco Valley mising the conservation of the the losses are due to a variety of and the Transition Toward the Future Patagonia National Park native biodiversity. -

The Roman Dogma of Animal Breeding: “Bark”Aeological Findings Reveal the Effects of Selective Pressures on Roman Dogs

Philomathes The Roman Dogma of Animal Breeding: “Bark”aeological Findings Reveal the Effects of Selective Pressures on Roman Dogs Introduction oman dogs were beloved by their masters, to a degree R similar to which dogs and owners bond today.1 Dogs were kept by their masters for four primary purposes: to work as hunting dogs, herding dogs, or guard dogs, and to be kept as lap dogs. Each role had various requirements that the dog must meet. Hunting and herding dogs must be fast, guard dogs must be intimidating, and lap dogs must be small. From these selective pressures, we can see the emergence of different categories of dogs in the ancient world. I say “categories” because they are not necessarily breeds in this case, as the Romans defined their dog breeds based on where a dog originated geographically, and not by traits shared amongst a group of similar dogs. 2 It is commonly accepted that the Romans were the first peoples in Europe to develop the modern forms of selection we use in breeding today.3 1 I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Liane Houghtalin, and my secondary readers, Dr. Joseph Romero and Dr. Angela Pitts at the University of Mary Washington, for helping me through the process of research. All translations are my own. 2 Michael Mackinnon, “‘Sick as a dog’: Zooarchaeological Evidence for Pet Dog Health and Welfare in the Roman World.” World Archaeology 42, no. 2 (2010): 292. 3 M. Zedda et al., “Ancient Pompeian Dogs–Morphological and Morphometric Evidence for Different Canine Populations.” Anatomia, 1 Philomathes The majority of existing scholarship explores the roles of dogs in Rome and the views that the Romans had about dogs. -

D.O.G. TALK from D.O.G

D.O.G. TALK from D.O.G. OBEDIENCE GROUP * * LIVING WITH DOGS Understanding Motivation Motivation is what makes your dog tick. It’s what drives him to do things, like respond to your cues and fi nd doing so worthwhile—even the second and third times you ask. Common canine motivators include: Car rides, a ball tossed, a walk, a leash clipped on or off , playing with toys, access to other dogs, access to smells, and—the biggie—food. Why should you know what motivates your dog? Because you can give him reason to pay attention to you. It’s the equivalent of saying to your dog, “I’ll tell you what: If you sit, I’ll throw your ball” or “If you stop pulling on the leash, I’ll let you go smell that fi re hydrant.” You use what naturally motivates your dog to get the behaviors you want most. So how do you go about it? First, limit your dog’s access to the things he fi nds most motivating. Have a ball-crazy dog? Instead of leaving balls around the house at all times, carry them with you so you can whip one out as a way to reward your dog when he is getting something right. Second, make an item more exciting by bringing it to life for your dog. Simply handing him a toy isn’t nearly as fun for a dog as shaking it about, playing peek-a-boo with it, and then, at the height of excitement, asking for a behavior and rewarding it with a toss of the toy. -

Domestic Dog Breeding Has Been Practiced for Centuries Across the a History of Dog Breeding Entire Globe

ANCESTRY GREY WOLF TAYMYR WOLF OF THE DOMESTIC DOG: Domestic dog breeding has been practiced for centuries across the A history of dog breeding entire globe. Ancestor wolves, primarily the Grey Wolf and Taymyr Wolf, evolved, migrated, and bred into local breeds specific to areas from ancient wolves to of certain countries. Local breeds, differentiated by the process of evolution an migration with little human intervention, bred into basal present pedigrees breeds. Humans then began to focus these breeds into specified BREED Basal breed, no further breeding Relation by selective Relation by selective BREED Basal breed, additional breeding pedigrees, and over time, became the modern breeds you see Direct Relation breeding breeding through BREED Alive migration BREED Subsequent breed, no further breeding Additional Relation BREED Extinct Relation by Migration BREED Subsequent breed, additional breeding around the world today. This ancestral tree charts the structure from wolf to modern breeds showing overlapping connections between Asia Australia Africa Eurasia Europe North America Central/ South Source: www.pbs.org America evolution, wolf migration, and peoples’ migration. WOLVES & CANIDS ANCIENT BREEDS BASAL BREEDS MODERN BREEDS Predate history 3000-1000 BC 1-1900 AD 1901-PRESENT S G O D N A I L A R T S U A L KELPIE Source: sciencemag.org A C Many iterations of dingo-type dogs have been found in the aborigine cave paintings of Australia. However, many O of the uniquely Australian breeds were created by the L migration of European dogs by way of their owners. STUMPY TAIL CATTLE DOG Because of this, many Australian dogs are more closely related to European breeds than any original Australian breeds. -

Estimating the Economic Value of Australian Stock Herding Dogs

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 5-2014 Estimating the Economic Value of Australian Stock Herding Dogs E. R. Arnott University of Sydney J. B. Early University of Sydney C. M. Wade University of Sydney P. D. McGreevy University of Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/spwawel Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arnott, E. R., Early, J. B., Wade, C. M., & McGreevy, P. D. (2014). Estimating the economic value of Australian stock herding dogs. Animal Welfare, 23(2), 189-197. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Estimating the Economic Value of Australian Stock Herding Dogs ER Amott, JB Early, CM Wade and PD McGreevy University of Sydney KEYWORDS animal welfare, canine value, farm economics, owner survey, stock herding, working dog ABSTRACT This study aimed to estimate the value of the typical Australian herding dog in terms of predicted return on investment. This required an assessment of the costs associated with owning herding dogs and estimation of the work they typically perform. Data on a total of 4,027 dogs were acquired through The Farm Dog Survey which gathered information from 812 herding dog owners around Australia. The median cost involved in owning a herding dog was estimated to be a total of AU$7,763 over the period of its working life. The work performed by the dog throughout this time was estimated to have a median value of AU$40,000. -

Investigating Emotional Contagion in Dogs (Canis Familiaris) to Emotional Sounds of Humans and Conspecifics

Anim Cogn DOI 10.1007/s10071-017-1092-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Investigating emotional contagion in dogs (Canis familiaris) to emotional sounds of humans and conspecifics 1 1 2 1 Annika Huber • Anjuli L. A. Barber • Tama´s Farago´ • Corsin A. Mu¨ller • Ludwig Huber1 Received: 1 October 2016 / Revised: 10 April 2017 / Accepted: 12 April 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Emotional contagion, a basic component of emotional state-matching or emotional contagion for neg- empathy defined as emotional state-matching between ative sounds of humans and conspecifics. It furthermore individuals, has previously been shown in dogs even upon indicates that dogs recognized the different valences of the solely hearing negative emotional sounds of humans or emotional sounds, which is a promising finding for future conspecifics. The current investigation further sheds light studies on empathy for positive emotional states in dogs. on this phenomenon by directly contrasting emotional sounds of both species (humans and dogs) as well as Keywords Empathy Á Emotional contagion Á Playback opposed valences (positive and negative) to gain insights study Á Dogs into intra- and interspecies empathy as well as differences between positively and negatively valenced sounds. Dif- ferent types of sounds were played back to measure the Introduction influence of three dimensions on the dogs’ behavioural response. We found that dogs behaved differently after Empathy is a social phenomenon that can be defined as hearing non-emotional sounds of their environment com- ‘‘the capacity to […] be affected by and share the emo- pared to emotional sounds of humans and conspecifics tional state of another’’ (de Waal 2008, p. -

Performance Puppy by Helen Grinnell King

There are always tradeoffs in structure. You “ must know your sport and what it takes to “ excel in that sport and choose accordingly. PICKING YOUR PERFORMANCE PUPPY by Helen Grinnell King OBEDIENCE :: AGILITY :: FLYBALL :: SCHUTZHUND :: CONFORMATION :: SEARCH AND RESCUE :: RALLY OBEDIENCE :: DISC DOG :: :: DOCK DOGS :: TRACKING :: HERDING :: EARTH DOG :: LURE COURSING :: HUNTING :: CARTING :: OBEDIENCE :: AGILITY :: FLYBALL :: SCHUTZHUND :: CONFORMATION :: SEARCH AND RESCUE :: RALLY OBEDIENCE :: DISC DOG :: DOCK DOGS :: TRACKING :: HERDING :: EARTH DOG :: LURE COURSING :: HUNTING :: CARTING :: OBEDIENCE :: AGILITY :: FLYBALL :: SCHUTZHUND :: CONFORMATION :: SEARCH AND RESCUE :: RALLY OBEDIENCE :: TRACKING :: HERDING :: EARTH DOG :: LURE COURSING :: HUNTING :: CARTING :: OBEDIENCE :: PICKING YOUR PERFORMANCE PUPPY | 1 Does your puppy have the makings to be an athletic superstar? Copyright © 2012 Helen Grinnell King All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without written permission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty of fitness is implied. The information is provided on an as-is basis. The authors and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained -

Courthouse Dogs Is Not Recommended for Use with Islamic Populations Due to Religious Regulations

Understand what basic elements should be in place to successfully start a facility dog program Understand why creating a trauma-sensitive courtroom and Dependency experience is essential to our work Illustrate through a case study how inter- agency collaboration equals success for kids Animals have been used to promote therapeutic outcomes for years with disabled children. Animals promote self-regulation, verbal expression and increased independence in therapeutic interactions with children. Bringing dogs into the courtroom bridges the gap by reducing the adversarial nature of the courtroom into a more trauma-sensitive environment allowing children to express themselves and their wishes to the court. Children are vulnerable by nature of their age, immaturity, lack of authority, and inability to self-advocate, self defend. 49% of perpetrators (usually family members or family friends who have private access to a child) stated that they targeted children with low self-confidence and low self-esteem. -(Elliott et al., 1995)-Courtesy of David Crenshaw, Ph.D. Seven years old. Removed in Fall, 2014 due to multiple concerns including bizarre punishment. Placed in Licensed Foster Care at removal. The Department has filed an expedited petition for termination of parental rights. Visits with parent weekly, supervised by the Department. Twelve minute interaction with a dog has been shown to lower blood pressure, neurohormone levels, and anxiety of hospitalized cardiac patients. (Cole et al, 2007) Stroking and talking to dogs resulted in increased oxytocin levels, beta endorphins & dopamine, and decreased blood pressure & cortisol levels. (Fine & Beck, 2010) A single AAT (animal assisted therapy) session was associated with reduced anxiety for patients hospitalized with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and other psychiatric diagnoses. -

Livestock Guarding Dogs: Their Current Use World Wide

Copyright © 2001 by The Canid Specialist Group. The following is the established format for referencing this article: Rigg, R. 2001. Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group Occasional Paper No 1 [online] URL: http://www.canids.org/occasionalpapers/ Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide by Robin Rigg1* 1Department of Zoology, University of Aberdeen, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen AB24 2TZ, UK. e-mail: [email protected] *Current address: Pribylina 150, 032 42, Slovakia. Robin Rigg is currently a postgraduate research student on the project Protection of Livestock and the Conservation of Large Carnivores in Slovakia, which he co-authored and launched in 2000. His research is focussed on the use of livestock guarding dogs to reduce predation on sheep and goats and a study of wolf and bear feeding ecology in the Western Carpathi ans. He has been working on a variety of other wolf and forest conservation projects in Slovakia since 1996. Livestock guarding dogs: their current use world wide Acknowledgements Thanks go to Dr. Claudio Sillero of the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) at Oxford University for his guidance on the initial outline and sources for this report as well as later comments on a draft; Dr. Martyn Gorman of the University of Aberdeen Zoology Department for advice and supervision; the staff of the Oxford University zoology libraries and Queen Elizabeth House library, the Balfour Library and Cambridge University Periodicals Library, University of Aberdeen