Strongman Rising What a Rodrigo Duterte Presidency Will Mean for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ateneo Factcheck 2016

FactCheck/ Information Brief on Peace Process (GPH/MILF) and an Autonomous Bangsamoro Western Mindanao has been experiencing an armed conflict for more than forty years, which claimed more than 150,000 souls and numerous properties. As of 2016 and in spite of a 17-year long truce between the parties, war traumas and chronic insecurity continue to plague the conflict-affected areas and keep the ARMM in a state of under-development, thus wasting important economic opportunities for the nation as a whole. Two major peace agreements and their annexes constitute the framework for peace and self- determination. The Final Peace Agreement (1996) signed by the Moro National Liberation Front and the government and the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (2014), signed by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, both envision – although in different manners – the realization of self-governance through the creation of a (genuinely) autonomous region which would allow the Moro people to live accordingly to their culture and faith. The Bangsamoro Basic Law is the emblematic implementing measure of the CAB. It is a legislative piece which aims at the creation of a Bangsamoro Political Entity, which should enjoy a certain amount of executive and legislative powers, according to the principle of subsidiarity. The 16th Congress however failed to pass the law, despite a year-long consultative process and the steady advocacy efforts of many peace groups. Besides the BBL, the CAB foresees the normalization of the region, notably through its socio-economic rehabilitation and the demobilization and reinsertion of former combatants. The issue of peace in Mindanao is particularly complex because it involves: - Security issues: peace and order through security sector agencies (PNP/ AFP), respect of ceasefires, control on arms;- Peace issues: peace talks (with whom? how?), respect and implementation of the peace agreements;- But also economic development;- And territorial and governance reforms to achieve regional autonomy. -

Pacnet Number 23 May 6, 2010

Pacific Forum CSIS Honolulu, Hawaii PacNet Number 23 May 6, 2010 Philippine Elections 2010: Simple Change or True problem is his loss of credibility stemming from his ouster as Reform? by Virginia Watson the country’s president in 2001 on charges of corruption. Virginia Watson [[email protected]] is an associate Survey results for vice president mirror the presidential professor at the Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies in race. Aquino’s running mate, Sen. Manuel Roxas, Jr. has Honolulu. pulled ahead with 37 percent. Sen. Loren Legarda, in her second attempt at the vice presidency, dropped to the third On May 10, over 50 million Filipinos are projected to cast spot garnering 20 percent, identical to the results of the their votes to elect the 15th president of the Philippines, a Nacionalista Party’s presidential candidate, Villar. Estrada’s position held for the past nine years by Gloria Macapagal- running mate, former Makati City Mayor Jejomar “Jojo” Arroyo. Until recently, survey results indicated Senators Binay, has surged past Legarda and he is now in second place Benigno Aquino III of the Liberal Party and Manuel Villar, Jr. with 28 percent supporting his candidacy. of the Nacionalista Party were in a tight contest, but two weeks from the elections, ex-president and movie star Joseph One issue that looms large is whether any of the top three Estrada, of the Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino, gained ground to contenders represents a new kind of politics and governance reach a statistical tie with Villar for second place. distinct from Macapagal-Arroyo, whose administration has been marked by corruption scandals and human rights abuses Currently on top is “Noynoy” Aquino, his strong showing while leaving the country in a state of increasing poverty – the during the campaign primarily attributed to the wave of public worst among countries in Southeast Asia according to the sympathy following the death of his mother President Corazon World Bank. -

The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines Lisandro Claudio

The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines Lisandro Claudio To cite this version: Lisandro Claudio. The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines. 2019. halshs-03151036 HAL Id: halshs-03151036 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03151036 Submitted on 2 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EUROPEAN POLICY BRIEF COMPETING INTEGRATIONS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The Erosion of Liberalism and the Rise of Duterte in the Philippines This brief situates the rise and continued popularity of President Rodrigo Duterte within an intellectual history of Philippine liberalism. First, the history of the Philippine liberal tradition is examined beginning in the nineteenth century before it became the dominant mode of elite governance in the twentieth century. It then argues that “Dutertismo” (the dominant ideology and practice in the Philippines today) is both a reaction to, and an assault on, this liberal tradition. It concludes that the crisis brought about by the election of Duterte presents an opportunity for liberalism in the Philippines to be reimagined to confront the challenges faced by this country of almost 110 million people. -

Psychographics Study on the Voting Behavior of the Cebuano Electorate

PSYCHOGRAPHICS STUDY ON THE VOTING BEHAVIOR OF THE CEBUANO ELECTORATE By Nelia Ereno and Jessa Jane Langoyan ABSTRACT This study identified the attributes of a presidentiable/vice presidentiable that the Cebuano electorates preferred and prioritized as follows: 1) has a heart for the poor and the needy; 2) can provide occupation; 3) has a good personality/character; 4) has good platforms; and 5) has no issue of corruption. It was done through face-to-face interview with Cebuano registered voters randomly chosen using a stratified sampling technique. Canonical Correlation Analysis revealed that there was a significant difference as to the respondents’ preferences on the characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across respondents with respect to age, gender, educational attainment, and economic status. The strength of the relationships were identified to be good in age and educational attainment, moderate in gender and weak in economic status with respect to the characteristics of the presidentiable. Also, there was a good relationship in age bracket, moderate relationship in gender and educational attainment, and weak relationship in economic status with respect to the characteristics of a vice presidentiable. The strength of the said relationships were validated by the established predictive models. Moreover, perceptual mapping of the multivariate correspondence analysis determined the groupings of preferred characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across age, gender, educational attainment and economic status. A focus group discussion was conducted and it validated the survey results. It enumerated more characteristics that explained further the voting behavior of the Cebuano electorates. Keywords: canonical correlation, correspondence analysis perceptual mapping, predictive models INTRODUCTION Cebu has always been perceived as "a province of unpredictability during elections" [1]. -

Southeast Asia from Scott Circle

Chair for Southeast Asia Studies Southeast Asia from Scott Circle Volume VII | Issue 4 | February 18, 2016 A Tumultuous 2016 in the South China Sea Inside This Issue gregory poling biweekly update Gregory Poling is a fellow with the Chair for Southeast Asia • Myanmar commander-in-chief’s term extended Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in amid fragile talks with Aung San Suu Kyi Washington, D.C. • U.S., Thailand hold annual Cobra Gold exercise • Singapore prime minister tables changes to February 18, 2016 political system • Obama hosts ASEAN leaders at Sunnylands This promises to be a landmark year for the claimant countries and other summit interested parties in the South China Sea disputes. Developments that have been under way for several years, especially China’s island-building looking ahead campaign in the Spratlys and Manila’s arbitration case against Beijing, will • Kingdom at a Crossroad: Thailand’s Uncertain come to fruition. These and other developments will draw outside players, Political Trajectory including the United States, Japan, Australia, and India, into greater involvement. Meanwhile a significant increase in Chinese forces and • 2016 Presidential and Congressional Primaries capabilities will lead to more frequent run-ins with neighbors. • Competing or Complementing Economic Visions? Regionalism and the Pacific Alliance, Alongside these developments, important political transitions will take TPP, RCEP, and the AIIB place around the region and further afield, especially the Philippine presidential elections in May. But no matter who emerges as Manila’s next leader, his or her ability to substantially alter course on the South China Sea will be highly constrained by the emergence of the issue as a cause célèbre among many Filipinos who view Beijing with wariness bordering on outright fear. -

Freedom in the World 2016 Philippines

Philippines Page 1 of 8 Published on Freedom House (https://freedomhouse.org) Home > Philippines Philippines Country: Philippines Year: 2016 Freedom Status: Partly Free Political Rights: 3 Civil Liberties: 3 Aggregate Score: 65 Freedom Rating: 3.0 Overview: A deadly gun battle in January, combined with technical legal challenges, derailed progress in 2015 on congressional ratification of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BLL), under which a new self-governing region, Bangsamoro, would replace and add territory to the current Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The BLL was the next step outlined in a landmark 2014 peace treaty between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the country’s largest rebel group. The agreement, which could end more than 40 years of separatist violence among Moros, as the region’s Muslim population is known, must be approved by Congress and in a referendum in Mindanao before going into effect. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino’s popularity suffered during the year due to his role in the January violence—in which about 70 police, rebels, and civilians were killed—and ongoing corruption. Presidential and legislative elections were scheduled for 2016. In October, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, the Netherlands, ruled that it had jurisdiction to hear a case filed by the Philippines regarding its dispute with China over territory in the South China Sea, despite objections from China. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: https://freedomhouse.org/print/48102 4/19/2018 Philippines Page 2 of 8 Political Rights: 27 / 40 (+1) [Key] A. Electoral Process: 9 / 12 The Philippines’ directly elected president is limited to a single six-year term. -

Duterte and Philippine Populism

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ASIA, 2017 VOL. 47, NO. 1, 142–153 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751 COMMENTARY Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism Nicole Curato Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance, University of Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This commentary aims to take stock of the 2016 presidential Published online elections in the Philippines that led to the landslide victory of 18 October 2016 ’ the controversial Rodrigo Duterte. It argues that part of Duterte s KEYWORDS ff electoral success is hinged on his e ective deployment of the Populism; Philippines; populist style. Although populism is not new to the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte; elections; Duterte exhibits features of contemporary populism that are befit- democracy ting of an age of communicative abundance. This commentary contrasts Duterte’s political style with other presidential conten- ders, characterises his relationship with the electorate and con- cludes by mapping populism’s democratic and anti-democratic tendencies, which may define the quality of democratic practice in the Philippines in the next six years. The first six months of 2016 were critical moments for Philippine democracy. In February, the nation commemorated the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution – a series of peaceful mass demonstrations that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III – the son of the president who replaced the dictator – led the commemoration. He asked Filipinos to remember the atrocities of the authoritarian regime and the gains of democracy restored by his mother. He reminded the country of the torture, murder and disappearance of scores of activists whose families still await compensation from the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board. -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

Senatoriables and the Anti-Political Dynasty Bill Claim

Ateneo FactCheck 2013 Fourth Brief Fact Check: Senatoriables and the Anti-Political Dynasty Bill Claim: Candidates, who are members of political dynasties, will not champion or will not support an anti-political dynasty bill in Congress; while candidates, who are NOT members of any political dynasty, are expected to champion and support an anti-dynasty bill. Fact checked: The 1987 Constitution prohibits political dynasties but left it to Congress to enact an enabling anti-political dynasty law. Exactly 26 years after the constitution was enacted and despite several attempts, no such law has been passed by either chamber of Congress. All versions of the bill have not even gone way past the committee level for second reading. Now that the 2013 midterm election is coming, what is to be expected from at least the top 20 candidates vying for a seat in the Senate? While an exact definition is still elusive, it is liberally accepted that political dynasties are those candidates who have more than one family member in any elective public position or are running for elective positions and holding such position for several terms before passing it on to either the immediate or extended family members. Generally the top 20 candidates for the Senate, according to major survey outfits, are dominated by members of well-known political dynasties. Exactly 13 out of the 20 are members of dynasties, namely: Sonny Angara, Bam Aquino, Nancy Binay, Alan Cayetano, Ting-Ting Cojuangco, JV Ejercito, Jack Enrile, Chiz Escudero, Dick Gordon, Ernesto Maceda, Jun Magsaysay, Cynthia Villar and Mig Zubiri. Except for newcomers like Bam Aquino and Nancy Binay, most candidates are veteran or experienced politicians in Congress. -

April 16, 2016 Hawaii Filipino Chronicle 1

April 16, 2016 hAwAii Filipino chronicle 1 ♦ APRIL 16, 2016 ♦ CANDID PERSPECTIVES BUSINESS FEATURE MAINLAND NEWS GriDlock thAt workS: AlohA Sweet city oF SAn FrAnciSco UnionS Get booSt From DeliteS ServeS Up ApproveS Filipino coUrt DeADlock DelectAble treAtS cUltUrAl DiStrict PRESORTED HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 hAwAii Filipino chronicle April 16, 2016 EDITORIAL FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor ll eyes will be on the Philippines Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. Filipino Voters to in the coming weeks, as frenzy Publisher & Managing Editor and interest in the national elec- Chona A. Montesines-Sonido Decide Philippines’ tions are sure to reach a fevered Associate Editors Dennis Galolo | Edwin Quinabo pitch. And for good reason. The A Contributing Editor Future in 2016 Election May 9th election will determine Belinda Aquino, Ph.D. s far as elections go, one can probably argue that the nation’s leaders in all levels and Creative Designer Junggoi Peralta the Philippines has come a long way since the days branches of government—from president to provincial, city and municipal level offices. The big prize, of Photography when grandiose showmanship during song-and- Tim Llena dance-filled campaign trails was all that mattered. course, is Malacañang, where leading candidates Manuel Administrative Assistant It has also come a long way since those days when “Mar” Roxas II, Jejomar “Jojo” Binay, Grace Poe, Rodrigo Shalimar Pagulayan A Columnists Duterte and Miriam Defensor Santiago all have their eyes electoral frauds were seen as rampant. -

TIMELINE: the ABS-CBN Franchise Renewal Saga

TIMELINE: The ABS-CBN franchise renewal saga Published 4 days ago on July 10, 2020 05:40 PM By TDT Embattled broadcast giant ABS-CBN Corporation is now facing its biggest challenge yet as the House Committee on Legislative Franchises has rejected the application for a new broadcast franchise. The committee voted 70-11 in favor of junking ABS-CBN’s application for a franchise which dashed the hopes of the network to return to air. Here are the key events in the broadcast giant’s saga for a franchise renewal: 30 March, 1995 Republic Act 7966 or otherwise known as an act granting the ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation a franchise to construct, install, operate and maintain television and radio broadcasting stations in the Philippines granted the network its franchise until 4 May 2020. 11 September, 2014 House Bill 4997 was filed by Isabela Rep. Giorgidi Aggabao and there were some lapses at the committee level. 11 June, 2016 The network giant issued a statement in reaction to a newspaper report, saying that the company had applied for a new franchise in September 2014, but ABS-CBN said it withdrew the application “due to time constraints.” 5 May, 2016 A 30-second political ad showing children raising questions about then Presidential candidate Rodrigo Duterte’s foul language was aired on ABS-CBN and it explained it was “duty-bound to air a legitimate ad” based on election rules. 6 May, 2016 Then Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte’s running mate Alan Peter Cayetano files a temporary restraining order in a Taguig court against the anti-Duterte political advertisement. -

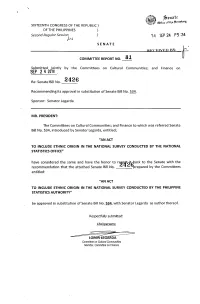

LO.I~MDA Commillee on Cultural Communities Member, Commiffee on Finance .'

" \ 'senntr (~Ih;'. of Il]d··tn"I.. ~ SIXTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC) OF THE PHILIPPINES ) Second Regular Session ) '14 SEP 24 P5 :34 );--I SENATE RFCFIVF:n UY: COMMITTEE REPORT NO. 81 Submitted jOintly by the Committees on Cultural Communities; and Finance on SEP 2 4 2014 Re: Senate Bill No. 2426 Recommending its approval in substitution of Senate Bill No. 534. Sponsor: Senator Legarda MR. PRESIDENT: The Committe,es on Cultural Communities; and Finance to which was referred Senate Bill No. 534, introduced by Senator Legarda, entitled; "AN ACT TO INCLUDE ETHNIC ORIGIN IN THE NATIONAL SURVEY CONDUCTED BY THE NATIONAL STATISTICS OFFICE" have considered the same and have the honor to r29f2lfack to the Senate with the recommendation that the attached Senate Bill No. prepared by the Committees entitled: "AN ACT TO INCLUDE ETHNIC ORIGIN IN THE NATIONAL SURVEY CONDUCTED BY THE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY" be approved in substitution of Senate Bill No. 534, with Senator Legarda as author thereof. Respectfully submitted: Chairpersons: LO.i~MDA Commillee on Cultural Communities Member, Commiffee on Finance .' '''Nc7'"~SCUD'ROCommittee on Finance Vice Chairpersons: i/'~V ANT~~ A~~G'O R. OSMENA III CommiUee on Cultural Communities Committee on Finance Members: RA RAMON BONG REVILLA, JR. Committee on Cultural Communities Committee on Cultural Communities Committee on Finance Committee on Finance ~~(l~LM'rW PAOL~~I~NOS;;AM"~QUINO IV Commi/lee on Cultural Communities CommiUee Cultural Communities Committee on Finance TEOFISTO L. GUINGONA III Committee on Finance FERDINAN R. i\¥RCOS, JR. Committee on inance AQUILINO "KOKO" PIMENTEL III GRACE POE Committee on Finance Committee on Finance CYNTHIA A.