Articulation in Mozart's Piano and Violin Sonatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EW Hollywood Orchestra Opus Edition User Manual

USER MANUAL 1.0.6 < CONTENTS HOLLYWOOD ORCHESTRA OPUS EDITION INFORMATION The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of East West Sounds, Inc. The software and sounds described in this document are subject to License Agreements and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by East West Sounds, Inc. All product and company names are ™ or ® trademarks of their respective owners. Solid State Logic (SSL) Channel Strip, Transient Shaper, and Stereo Compressor licensed from Solid State Logic. SSL and Solid State Logic are registered trademarks of Red Lion 49 Ltd. © East West Sounds, Inc., 2021. All rights reserved. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA 1-323-957-6969 voice 1-323-957-6966 fax For questions about licensing of products: [email protected] For more general information about products: [email protected] For technical support for products: http://www.soundsonline.com/Support < CONTENTS HOLLYWOOD ORCHESTRA OPUS EDITION CREDITS PRODUCERS Doug Rogers, Nick Phoenix, Thomas Bergersen SOUND ENGINEER Shawn Murphy ENGINEERING ASSISTANCE Jeremy Miller, Ken Sluiter, Bo Bodnar PRODUCTION COORDINATORS Doug Rogers, Blake Rogers, Rhys Moody PROGRAMMING / SOUND DESIGN Justin Harris, Jason Coffman, Doug Rogers, Nick Phoenix SCRIPTING Wolfgang Schneider, Thomas Bergersen, Klaus Voltmer, Patrick Stinson -

Beethoven Op. 131 Manuscript Markings NK 20170701.Pages

A paper by Nicholas Kitchen about manuscript markings in Beethoven in general and in particular about their use in Op. 131, expanded from a paper presented for the Boston University Beethoven Institute in April 2017 I am honored to share with you today some of the exciting surprises that have come from rehearsing and performing directly from pdf files of Beethoven's manuscripts. The Beethoven editions I first encountered (at least for quartets) were the Joachim- Moser editions, which I now see as lovingly mauled editorial efforts. Regardless of any editions, I heard beautiful performances of Beethoven's music, treasures in my memory that continually inspire my current endeavors to try to bring the beauty of his compositions to life. But the particular beauty of Beethoven quickly demands from us the realization that the details of our interface with the markings in his music DO matter a great deal, and that they mattered a great deal to Beethoven himself. Studying at Curtis, I witnessed the transition to Henle Urtext as the trusted source of learning about Beethoven. My single most inspiring class was one led by my teacher Szymon Goldberg, where all of his students had our Henle piano scores of all ten Beethoven Sonatas (we also consulted Joachim's solutions to certain issues) and all together we went through all ten sonatas multiple times, with all of us taking turns performing different Sonatas. Mr. Goldberg made vivid to us the concept that !1 of 92! Beethoven's markings were living instructions from one virtuoso performer to another, and he had a nice saying: "The composer wants the performance to succeed even MORE than you do". -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands An

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands and demonstrates appropriate playing posture without prompts OR.PP.2 Understands and demonstrates correct finger/hand position without prompts OR.AR Articulation OR.AR.1 Interprets and performs combinations of bowing at an advanced level [tie, slur, staccato, hooked bowings, loure (portato) bowing, accent, spiccato, syncopation, and legato] OR.AR.2 Interprets and performs Ricochet, Sul Ponticello, and Sul Tasto bowings at a beginning level OR.TQ Tone Quality OR.TQ.1 Produces a characteristic tone at the medium-advanced level OR.TQ.2 Defines and performs proper ensemble balance and blend at the medium-advanced level OR.RT Rhythm/Tempo OR.RT.1 Defines and performs rhythm patterns at the medium-advanced level (quarter note/rest, half note/rest, eighth note/rest, dotted eighth note, dotted half note, whole note/rest, dotted quarter note, sixteenth note) OR.RT.2 Defines and performs tempo markings at a medium-advanced level (Allegro, Moderato, Andante, Ritardando, Lento, Andantino, Maestoso, Andante Espressivo, Marziale, Rallantando, and Presto) OR.TE Technique OR.TE.1 Performs the pitches and the two-octave major scales for C, G, D, A, F, Bb, Eb; performs the pitches and the two-octave minor scales for A, E, D, G, C; performs the pitches and the one-octave chromatic scale OR.TE.2 Demonstrates and performs pizzicato, acro, and left-hand pizzicato at the medium-advanced level OR.TE.3 Demonstrates shifting at the intermediate -

Ornamentos-Musicais.Pdf

JEAN RICARDO MARQUES ORNAMENTOS Musicais SALVADOR 2014 1 SUMÁRIO 1. INTRODUÇÃO ...............................................................................................3 2. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA ERUDITA ......................................3 3. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA POPULAR ....................................8 4. CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS ..........................................................................12 REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ................................................................ 13 2 1. INTRODUÇÃO Este estudo trata dos ornamentos na música erudita, também chamados de “efeitos” na música popular. Em música, são chamados ornamentos os embelezamentos e decorações de uma melodia, expressos através de pequenas notas ou sinais especiais. A ornamentação fazia muito sentido nos séculos XIV até XVI devido ao amplo uso do Cravo. Este instrumento por sua vez, não segurava uma nota por tanto tempo quanto o Piano, deixando assim lacunas entre uma nota e outra ou o término de um tema e o início de um desenvolvimento/cadência. Desta forma os ornamentos tornaram-se amplamente utilizados neste período. Na musica Erudita, os ornamentos possuem características próprias sobre as notas que englobam e as notas que acrescentam. São eles o: Trinado (ou Trilo), Mordente, Grupetto (ou Gruppeto, Gruppetto, Grupeto), Appoggiatura (ou Apogiatura, Apojatura), Floreio, Portamento, Cadência (ou Cadenza), Arpeggio (ou Arpejo, Harpejo) e Glissando. Ornamentos na música popular consistem em extrair sonoridades e interpretações diferentes que incidem sobre determinado trecho musical, mediante a utilização de diversos sistemas de execução. Esses efeitos tem origem na guitarra elétrica e foram adaptados e usados nos baixos elétrico e são, em parte, aquilo que define a peculiaridade do músico. 2. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA ERUDITA Segue abaixo os ornamentos mais usados na música erudita: a) Trinado Esta representado por um tr colocado sempre acima da nota independente se ela tem a haste virada para cima ou para baixo. -

Musixtex Using TEX to Write Polyphonic Or Instrumental Music Version T.111 – April 1, 2003

c MusiXTEX Using TEX to write polyphonic or instrumental music Version T.111 – April 1, 2003 Daniel Taupin Laboratoire de Physique des Solides (associ´eau CNRS) bˆatiment 510, Centre Universitaire, F-91405 ORSAY Cedex E-mail : [email protected] Ross Mitchell CSIRO Division of Atmospheric Research, Private Bag No.1, Mordialloc, Victoria 3195, Australia Andreas Egler‡ (Ruhr–Uni–Bochum) Ursulastr. 32 D-44793 Bochum ‡ For personal reasons, Andreas Egler decided to retire from authorship of this work. Never- therless, he has done an important work about that, and I decided to keep his name on this first page. D. Taupin Although one of the authors contested that point once the common work had begun, MusiXTEX may be freely copied, duplicated and used in conformance to the GNU General Public License (Version 2, 1991, see included file copying)1 . You may take it or parts of it to include in other packages, but no packages called MusiXTEX without specific suffix may be distributed under the name MusiXTEX if different from the original distribution (except obvious bug corrections). Adaptations for specific implementations (e.g. fonts) should be provided as separate additional TeX or LaTeX files which override original definition. 1Thanks to Free Software Foundation for advising us. See http://www.gnu.org Contents 1 What is MusiXTEX ? 6 1.1 MusiXTEX principal features . 7 1.1.1 Music typesetting is two-dimensional . 7 1.1.2 The spacing of the notes . 8 1.1.3 Music tokens, rather than a ready-made generator . 9 1.1.4 Beams . 9 1.1.5 Setting anything on the score . -

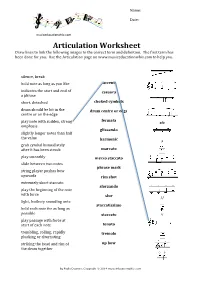

Articulation Worksheet Draw Lines to Link the Following Images to the Correct Term and Definition

Name: Date: !"#$%&'"%()$*+,-$./%*! Articulation Worksheet Draw lines to link the following images to the correct term and definition. The first term has been done for you. Use the Articulation page on www.musiceducationwhiz.com to help you. silence, break hold note as long as you like accent indicates the start and end of caesura a phrase short, detached choked cymbals drum should be hit in the drum centre or edge centre or on the edge fermata play note with sudden, strong sfz emphasis glissando slightly longer notes than half the value harmonic , grab cymbal immediately after it has been struck marcato play smoothly mezzo staccato slide between two notes phrase mark string player pushes bow upwards rim shot extremely short staccato sforzando play the beginning of the note with force slur // light, feathery sounding note staccatissimo hold each note for as long as possible staccato v play passage with force at start of each note tenuto trembling, rolling, rapidly tremolo plucking or alternating striking the head and rim of up bow the drum together By Paula Downes, Copyright © 2014 musiceducationwhiz.com !"#$%&'"%()$*+,-$./%*! Class Presentations Write definitions for at least ten of the following articulation terms (or any others you know), explaining which instrument or group of instruments they are used for. Find pieces of music that use these techniques and talk about them. If you don’t know any, do some internet research. Present your work to the class, performing the various articulations if possible. martellato, sticking, stopped drums, ghost notes, cross stick, prepared piano, una corda, sostenuto pedal, damper pedal, col legno, martelé, barricolage, ricochet, sautille, spiccato, portato, détaché, sul tasto, sul ponticello, point of contact, arco, pizzicato, snap pizzicato, dampening, L.V., legato slide, strumming patterns, flutter-tonguing, double and triple tonguing, tonguing, mute By Paula Downes, Copyright © 2014 musiceducationwhiz.com . -

Lilypond Music Glossary

LilyPond The music typesetter Music Glossary The LilyPond development team ☛ ✟ This glossary provides definitions and translations of musical terms used in the documentation manuals for LilyPond version 2.21.82. ✡ ✠ ☛ ✟ For more information about how this manual fits with the other documentation, or to read this manual in other formats, see Section “Manuals” in General Information. If you are missing any manuals, the complete documentation can be found at http://lilypond.org/. ✡ ✠ Copyright ⃝c 1999–2020 by the authors Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. For LilyPond version 2.21.82 1 1 Musical terms A-Z Languages in this order. • UK - British English (where it differs from American English) • ES - Spanish • I - Italian • F - French • D - German • NL - Dutch • DK - Danish • S - Swedish • FI - Finnish 1.1 A • ES: la • I: la • F: la • D: A, a • NL: a • DK: a • S: a • FI: A, a See also Chapter 3 [Pitch names], page 87. 1.2 a due ES: a dos, I: a due, F: `adeux, D: ?, NL: ?, DK: ?, S: ?, FI: kahdelle. Abbreviated a2 or a 2. In orchestral scores, a due indicates that: 1. A single part notated on a single staff that normally carries parts for two players (e.g. first and second oboes) is to be played by both players. -

Analysis of Reed Vibrations and Mouthpiece Pressure In

ISMA 2019 Analysis of reed vibration and mouthpiece pressure in contemporary bass clarinet playing techniques Peter Mallinger(1)∗, Montserrat Pàmies-Vilà(1), Vasileios Chatziioannou(1), Alex Hofmann(1)y (1)Dept. of Music Acoustics, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria Abstract While articulation on the B[-clarinet has already been a subject in various studies, articulation on the bass clarinet has gotten less attention. Because of the increasing interest for using the bass clarinet, especially in contemporary music, this instrument is emerging from the shadow of the B[-clarinet. In order to investigate articulation on the bass clarinet an experiment was carried out in an anechoic chamber at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna. A professional clarinetist was recorded performing different articulation techniques on a German bass clarinet under controlled performance conditions. Results show that the attack transients on the bass clarinet were about 0.085 s long in staccato articulation. In comparison, attack transients on the B[-clarinet are 2 to 3 times shorter. This study especially focuses on the slap tonguing technique. Of particular interest is the reed bending signal, which shows the movement of the reed. It has been observed that tones articulated with slap tonguing have a significantly shorter attack transient and are immediately entering the decay phase. Such measurements allow an in-depth analysis of player-instrument interactions with contem- porary playing techniques and may support the refinement of physical model parameters but may also support music education. Keywords : Bass clarinet, articulation, woodwinds, contemporary music, player-instrument interaction 1 INTRODUCTION Articulation techniques on the bass clarinet require precise control over the blowing pressure, the tongue and the embouchure as well as simultaneous fingering actions. -

Contemporary Music Score Collection

UCLA Contemporary Music Score Collection Title Otto Lamenti Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/73z9g148 Author Boccuzzi, Benedetto Publication Date 2020 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Benedetto Boccuzzi Otto Lamenti (2019) for solo violin and ensemble Preface Otto Lamenti is a cycle (in panels) for solo violin and ensemble in which both the musicians and the audience take a journey trough different emotional contexts and states of mind. From the profound pain of the praying mother to the (very serious!) barking of a dog that wants to go out; from a deep discomfort to the "electric bill complaining". A clash of contrasting meanings and atmospheres. The music is fragmented, theatrical and minimalistic at times, the panels are bonded by the silence. The musical breathing changes very sharply between powerful ensemble passages, and the loneliness of the solo violin. Dramatic cadenzas dissolve into static moments where melodies emerge. The music material echoes in different places throughout the piece. Formal Overview Solo violin and Ensemble Lamento 4 solo violin and ensemble accompanied by soft piano sounds [flute, oboe, clarinet in b flat, cello and piano] B - Cadenza, pesante ed apocalittico: the piano opens A - Semplice e religioso (introduction) solo violin with a sharp chord, the solo violin performs a cadenza Lamento 1 solo violin and ensemble B - Con eleganza, solo violin pizzicato melody and passage that ends with a flute flatterzung ensemble shorp gesture (x) C - Perdendosi: -

2021 Omta Theory Level Ten—Piano

1 2021 OMTA THEORY LEVEL TEN—PIANO Student’s Name____________________________________________________ Written Score Aural Score Teacher’s Name____________________________________________________ TOTAL SCORE Draw an enharmonic note next to each note given using whole notes. Use accidentals as needed. Draw one note under the arrow to complete one measure in the given time signatures. Draw one rest under the arrow to complete one measure in the given time signatures. Draw the key signatures. g minor F Major This is the key signature for _____ Major and for ______ minor. This is the key signature for _____ Major and for ______ minor. TURN TO THE NEXT PAGE 2 2021 OMTA THEORY LEVEL TEN—PIANO Write the name of the tonic note of each scale and circle whether the scale is Major, natural minor, harmonic minor, or melodic minor. Major natural minor Tonic:________ harmonic minor melodic minor Major natural minor Tonic:________ harmonic minor melodic minor Draw the scales one octave ascending and descending using whole notes. Use accidentals as needed in both directions. Do not use a key signature. G≤ Major d harmonic minor c melodic minor TURN TO THE NEXT PAGE 3 2021 OMTA THEORY LEVEL TEN—PIANO In the Major keys, label the chords as Tonic (I), Subdominant (IV), or Dominant 7th (V7). ___________ ___________ ___________ Draw the Tonic (I), Subdominant (IV), and Dominant (V) triads in root position. Use whole notes and accidentals as needed. D≤ Major: I IV V f minor: i iv V Label the intervals. Use Major, minor, Perfect, or Augmented in the answer. ___________ ___________ ___________ Draw the interval above each note using a whole note. -

Musixtex Using TEX to Write Polyphonic Or Instrumental Music Version 1.35

MusiXTEX Using TEX to write polyphonic or instrumental music Version 1.35 Revised August 29, 2021 If you are not familiar with TEX at all, I would recommend to find another software package to do musical typesetting. Setting up TEX and MusiXTEX on your machine and mastering it is an awesome job which gobbles up a lot of your time and disk space. But, once you master it... Hans Kuykens (ca. 1995) In my humble opinion, that whole statement is obsolete. Christof Biebricher (2006) ii MusiXTEX may be freely copied, duplicated and used in conformance to the GNU General Public License (Version 2, 1991, see included file copying)1. You may take it or parts of it to include in other packages, but no packages called MusiXTEX without specific suffix may be distributed under the name MusiXTEX if different from the original distribution (except obvious bug cor- rections). Adaptations for specific implementations (e.g., fonts) should be provided as separate additional TEXorLATEX files which override original definitions. 1Thanks to the Free Software Foundation for advice. See http://www.gnu.org Preface MusiXTEX was developed by Daniel Taupin, Ross Mitchell and Andreas Egler, building on earlier work by Andrea Steinbach and Angelika Schofer. Unfortunately, Daniel Taupin, the main developer, died all too early in a 2003 climbing accident. The MusiXTEX community was shocked by this tragic and unexpected event. You may read tributes to Daniel Taupin that are archived at the Werner Icking Music Archive (WIMA). Since then, the only significant update to MusiXTEX has been in version 1.15 (April 2011) which takes advantage of the greater capacity of the eTEX version of TEX.