A Teacher's Guide To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Déportés À Auschwitz. Certains Résis- Tion D’Une Centaine, Sont Traqués Et Tent Avec Des Armes

MORT1943 ET RÉSISTANCE BIEN QU’AYANT rarement connu les noms de leurs victimes juives, les nazis entendaient que ni Zivia Lubetkin, ni Richard Glazar, ni Thomas Blatt ne survivent à la « solution finale ». Ils survécurent cependant et, après la Shoah, chacun écrivit un livre sur la Résistance en 1943. Quelque 400 000 Juifs vivaient dans le ghetto de Varsovie surpeuplé, mais les épi- démies, la famine et les déportations à Treblinka – 300 000 personnes entre juillet et septembre 1942 – réduisirent considérablement ce nombre. Estimant que 40 000 Juifs s’y trouvaient encore (le chiffre réel approchait les 55 000), Heinrich Himmler, le chef des SS, ordonna la déportation de 8 000 autres lors de sa visite du ghetto, le 9 janvier 1943. Cependant, sous la direction de Mordekhaï Anielewicz, âgé de 23 ans, le Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ZOB, Organisation juive de combat) lança une résistance armée lorsque les Allemands exécutèrent l’ordre d’Himmler, le 18 janvier. Bien que plus de 5 000 Juifs aient été déportés le 22 janvier, la Résistance juive – elle impliquait aussi bien la recherche de caches et le refus de s’enregistrer que la lutte violente – empêcha de remplir le quota et conduisit les Allemands à mettre fin à l’Aktion. Le répit, cependant, fut de courte durée. En janvier, Zivia Lubetkin participa à la création de l’Organisation juive de com- bat et au soulèvement du ghetto de Varsovie. « Nous combattions avec des gre- nades, des fusils, des barres de fer et des ampoules remplies d’acide sulfurique », rapporte-t-elle dans son livre Aux jours de la destruction et de la révolte. -

The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo" (2016). Student Publications. 438. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/438 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 438 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Abstract The se cape of thousands of war criminals to Argentina and throughout South America in the aftermath of World War II is a historical subject that has been clouded with mystery and conspiracy. Lucía Puenzo's film, The German Doctor, utilizes this historical enigma as a backdrop for historical fiction by imagining a family's encounter with Josef Mengele, the notorious SS doctor from Auschwitz who escaped to South America in 1949 under a false identity. -

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Vichy France and the Jews

VICHY FRANCE AND THE JEWS MICHAEL R. MARRUS AND ROBERT 0. PAXTON Originally published as Vichy et les juifs by Calmann-Levy 1981 Basic Books, Inc., Publishers New York Contents Introduction Chapter 1 / First Steps Chapter 2 / The Roots o f Vichy Antisemitism Traditional Images of the Jews 27 Second Wave: The Crises of the 1930s and the Revival of Antisemitism 34 The Reach of Antisemitism: How Influential Was It? 45 The Administrative Response 54 The Refugee Crisis, 1938-41 58 Chapter 3 / The Strategy o f Xavier Vallat, i 9 4 !-4 2 The Beginnings of German Pressure 77 Vichy Defines the Jewish Issue, 1941 83 Vallat: An Activist at Work 96 The Emigration Deadlock 112 Vallat’s Fall 115 Chapter 4 / The System at Work, 1040-42 The CGQJ and Other State Agencies: Rivalries and Border Disputes 128 Business as Usual 144 Aryanization 152 Emigration 161 The Camps 165 Chapter 5 / Public Opinion, 1040-42 The Climax of Popular Antisemitism 181 The DistriBution of Popular Antisemitism 186 A Special Case: Algeria 191 The Churches and the Jews 197 X C ontents The Opposition 203 An Indifferent Majority 209 Chapter 6 / The Turning Point: Summer 1Q42 215 New Men, New Measures 218 The Final Solution 220 Laval and the Final Solution 228 The Effort to Segregate: The Jewish Star 234 Preparing the Deportation 241 The Vel d’Hiv Roundup 250 Drancy 252 Roundups in the Unoccupied Zone 255 The Massacre of the Innocents 263 The Turn in PuBlic Opinion 270 Chapter 7 / The Darquier Period, 1942-44 281 Darquier’s CGQJ and Its Place in the Regime 286 Darquier’s CGQJ in Action 294 Total Occupation and the Resumption of Deportations 302 Vichy, the ABBé Catry, and the Massada Zionists 310 The Italian Interlude 315 Denaturalization, August 1943: Laval’s Refusal 321 Last Days 329 Chapter 8 / Conclusions: The Holocaust in France . -

Kristallnacht Caption: Local Residents Watch As Flames Consume The

Kristallnacht Caption: Local residents watch as flames consume the synagogue in Opava, set on fire during Kristallnacht. Description of event: Literally, "Night of Crystal," is often referred to as the "Night of Broken Glass." The name refers to the wave of violent anti-Jewish pogroms which took place throughout Germany, annexed Austria, and in areas of the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia recently occupied by German troops. Instigated primarily by Nazi Party officials and members of the SA (Sturmabteilungen: literally Assault Detachments, but commonly known as Storm Troopers) and Hitler Youth, Kristallnacht owes its name to the shards of shattered glass that lined German streets in the wake of the pogrom- broken glass from the windows of synagogues, homes, and Jewish-owned businesses plundered and destroyed during the violence. Nuremberg Laws Caption: A young baby lies on a park bench marked with a J to indicate it is only for Jews. Description of event: Antisemitism and the persecution of Jews represented a central tenet of Nazi ideology. In their 25-point Party Program, published in 1920, Nazi party members publicly declared their intention to segregate Jews from "Aryan" society and to abrogate Jews' political, legal, and civil rights.Nazi leaders began to make good on their pledge to persecute German Jews soon after their assumption of power. During the first six years of Hitler's dictatorship, from 1933 until the outbreak of war in 1939, Jews felt the effects of more than 400 decrees and regulations that restricted all aspects of their public and private lives. Many of those laws were national ones that had been issued by the German administration and affected all Jews. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

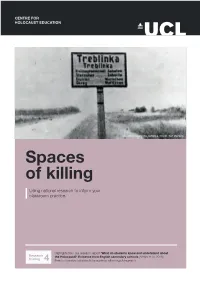

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom Through German-Jewish Eyes

Chapter 4 The Perpetrators of the November 1938 Pogrom through German-Jewish Eyes Alan E. Steinweis The November 1938 pogrom, often referred to as the “Kristallnacht,” was the largest and most significant instance of organized anti-Jewish violence in Nazi Germany before the Second World War.1 In addition to the massive destruc- tion of synagogues and property, the pogrom involved the physical abuse and terrorizing of German Jews on a massive scale. German police reported an official death toll of 91, but the actual number of Jews killed was probably about ten times that many when one includes fatalities among Jews who were treated brutally during their arrest and subsequent imprisonment in Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.2 Violence had been a normal feature of the Nazi regime’s anti-Jewish measures since 1933,3 but the scale and intensity of the Kristallnacht were unprecedented. The pogrom occurred less than one year before the outbreak of the war and the first atrocities by the Wehrmacht against Polish Jews, and less than three years before the Einsatzgruppen, Order Police, and other units began to undertake the mass murder of Jews in the Soviet Union. Knowledge about the perpetrators of the pogrom, therefore, pro- vides important context for understanding the violence that came later. To be sure, nobody has yet undertaken the extremely ambitious project to identify precisely which perpetrators of the Kristallnacht eventually would participate directly in the “Final Solution.” There certainly were many such cases, however, perhaps the most notable being Odilo Globocnik, who presided over the po- grom violence in Vienna in November 1938 and less than three years later was placed in charge of Operation Reinhardt, the mass murder of the Jews in the General Government.4 1 Many of the observations in this chapter are based on cases described and documented in the author’s book, Kristallnacht 1938 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). -

Holocaust Glossary

Holocaust Glossary A ● Allies: 26 nations led by Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union that opposed Germany, Italy, and Japan (known as the Axis powers) in World War II. ● Antisemitism: Hostility toward or hatred of Jews as a religious or ethnic group, often accompanied by social, economic, or political discrimination. (USHMM) ● Appellplatz: German word for the roll call square where prisoners were forced to assemble. (USHMM) ● Arbeit Macht Frei: “Work makes you free” is emblazoned on the gates at Auschwitz and was intended to deceive prisoners about the camp’s function (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Aryan: Term used in Nazi Germany to refer to non-Jewish and non-Gypsy Caucasians. Northern Europeans with especially “Nordic” features such as blonde hair and blue eyes were considered by so-called race scientists to be the most superior of Aryans, members of a “master race.” (USHMM) ● Auschwitz: The largest Nazi concentration camp/death camp complex, located 37 miles west of Krakow, Poland. The Auschwitz main camp (Auschwitz I) was established in 1940. In 1942, a killing center was established at Auschwitz-Birkenau (Auschwitz II). In 1941, Auschwitz-Monowitz (Auschwitz III) was established as a forced-labor camp. More than 100 subcamps and labor detachments were administratively connected to Auschwitz III. (USHMM) Pictured right: Auschwitz I. B ● Babi Yar: A ravine near Kiev where almost 34,000 Jews were killed by German soldiers in two days in September 1941 (Holocaust Museum Houston) ● Barrack: The building in which camp prisoners lived. The material, size, and conditions of the structures varied from camp to camp. -

Rethinking Hannah Arendt's Representation of The

Understanding, Reconciliation, and Prevention – Rethinking Hannah Arendt’s Representation of the Holocaust by Lindsay Shirley Macumber A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department for the Study of Religion University of Toronto © Copyright by Lindsay Shirley Macumber 2016 Understanding, Reconciliation, and Prevention: Rethinking Hannah Arendt’s Representation of the Holocaust Lindsay Shirley Macumber Doctor of Philosophy Centre for the Study of Religion University of Toronto 2016 Abstract In an effort to identify and assess the practical effects and ethical implications of representations of the Holocaust, this dissertation is a rethinking and evaluation of Hannah Arendt’s representation of the Holocaust according to the goal that she herself set out to achieve in thinking and writing about the Holocaust, understanding, or, “the unmediated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality- whatever it may be.”1 By examining Arendt’s confrontation with the Holocaust from within the context of systemic evil (which is how I argue she approached the Holocaust), and in light of her ultimate aim to “be at home in the world,” I conclude that understanding entails both reconciling human beings to the world after the unprecedented evil of the Holocaust, as well as working towards its prevention in the future. Following my introductory chapter, where I argue that Arendt provided an overall representation of the Holocaust, and delimit the criteria of reconciliation and prevention, each subsequent chapter is dedicated to an aspect I identify as central to her representation of the Holocaust: Her claim that totalitarianism was unprecedented; that the evil exemplified by Adolf Eichmann was “banal;” and that the Jewish Councils “cooperated” with the Nazis in the destruction of their communities.