Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master of Business Administration MBA Master of Business Administration

MBA Master of Business Administration MBA Master of Business Administration ABOUT MILPARK EDUCATION Milpark Education offers business education via distance and contact learning, focussing on the areas of management, commerce, financial planning and insurance, and banking across South Africa and in other parts of Africa. Milpark Education comprises several academic schools streamlined to provide the best experience to our varied student body within each school’s area of specialisation. Milpark’s Business School continues to offer its highly rated MBA while other schools will focus on their specialised range of offerings. Milpark has been rated as the Number One Private Provider of the MBA degree and was placed third in the overall rankings of accredited business schools in the 2014 PMR.africa national survey on accredited business schools offering MBA/MBL degrees in South Africa. REGISTRATION AND ACCREDITATION Milpark Education (Pty) Ltd is registered as a private higher education institution with the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) under the registration number 2007/HE07/003. All Milpark’s higher education programmes are accredited by the Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC), a permanent sub-committee of the Council on Higher Education (CHE). The Master in Business Administration has been accredited by the Council on Higher Education and is registered on the National Qualification Framework at Level 8 under the SAQA ID 62271. WHAT WILL THE MILPARK MBA DO FOR ME? A key objective of Milpark’s Business School is to enhance the potential of present and future business leaders in southern Africa by enabling them to compete successfully in the global marketplace. -

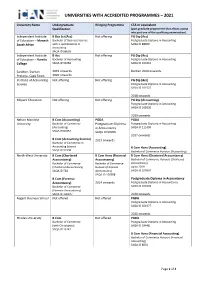

Universities with Accredited Programmes – 2021

UNIVERSITIES WITH ACCREDITED PROGRAMMES – 2021 University Name Undergraduate Bridging Programme CTA or equivalent Qualification (post graduate programme that allows access into part one of the qualifying examination) Independent Institute B Bus Sci (Acc) Not offering PG Dip (Acc) of Education – Monash Bachelor of Business Science Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting South Africa with a specialisation in SAQA ID 88609 Accounting SAQA ID 88603 Independent Institute B Acc Not offering PG Dip (Acc) of Education – Varsity Bachelor of Accounting Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting College SAQA ID 99284 SAQA ID 109416 Sandton, Durban 2019 onwards Durban 2020 onwards Pretoria, Cape Town 2020 onwards Institute of Accounting Not offering Not offering PG Dip (Acc) Science Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting SAQA ID 101527 2018 onwards Milpark Education Not offering Not offering PG Dip (Accounting) Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting SAQA ID 108930 2019 onwards Nelson Mandela B Com (Accounting) PGDA PGDA University Bachelor of Commerce Postgraduate Diploma Postgraduate Diploma in Accounting (Accounting) in Accountancy SAQA ID 115399 SAQA ID 87057 SAQA ID 90906 2017 onwards B Com (Accounting Science) 2013 onwards Bachelor of Commerce in Accounting Science B Com Hons (Accounting) SAQA ID 91998 Bachelor of Commerce Honours (Accounting) North-West University B Com (Chartered B Com Hons (Financial B Com Hons (Chartered Accountancy) Accountancy) Accountancy) Bachelor of Commerce Honours (Chartered Bachelor of Commerce Bachelor of Commerce Accountancy) (Chartered -

14 JULY 2017 21 July 2017 Tel: 011 531 1800 | [email protected]

SENIOR SCHOOL NEWS 14 JULY 2017 21 JUlY 2017 Tel: 011 531 1800 | [email protected] www.stmarysschool.co.za FROM THE HEAD’S DESK Over half-term, Kristen represented South Africa at the 21st World Transplant Games in Malaga, Spain. She was nominated for and won Best Female Junior Athlete. Well done, Kristen! My position requires me to focus my attention on the so-called among the girls that if they work hard they will achieve a good mark. big picture: the school as a whole organisation, educational This is certainly not true of all learning. Learning can be elusive: it is challenges, the strategic imperatives, the school’s positioning. dicult, frustrating and messy, and it may bring reward only after many Of late, one of the concerns that I have had is over an increase in hours of grappling with a question, a concept or a task. general anxiety of our pupils. A misconception of learning and the journey to achievement is what I am teaching Miss Nathanson’s Form II English class for half of this is driving our girls to become increasingly anxious about their studies. term while she is working on the Oxbridge program in the United The process of learning or education is not a smooth one that has Kingdom. To be back in the classroom is not only a wonderful a clear trajectory but, rather, it is a meandering path with phases of opportunity for me to enjoy the essence of our school and spend diculty, of ease, of achievement, of disappointment, of struggle. -

Editorial Sam Koma

Int. J. Management Practice, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2019 1 Editorial Sam Koma Milpark Business School, Extension 2, Melville, Johannesburg, South Africa Email: [email protected] Biographical notes: Sam Koma has over 15 years of academic experience contributing to teaching, research and community engagement. He is the author of the Handbook of South African Public Administration – a self-published book by Reach Publishers. He previously served as a Senior Lecturer at the University of Pretoria, School of Public Management and Administration before joining Milpark Education as the Head of the School of Government and Public Management in 2017 and currently heading the Department of Research in the Business School. He is a sought after expert by media houses in South Africa. He is also internationally well-travelled. This special issue examines management practices in African public sector organisations. The aims of this special issue are, first, to provide African scholars with a platform to showcase their work and communicate with one another within the international marketplace of academic ideas and secondly, to inform the global readership of this journal about a continent whose management and governance practices are not well-known. The subject coverage includes topics encompassing public sector administrative reforms and innovations; corporate governance and risk management; contracting out of public services, monitoring and evaluation; and leadership. The first paper, ‘Progress made towards achieving Rwanda’s Vision 2020 key indicators’ targets’ by Dominique Uwizeyimana examines the potential significance of monitoring and evaluation related to the interim evaluation report on the Government of Rwanda’s (GoR) progress towards achieving the objectives of Vision 2020 after 17 years of its implementation. -

Register of Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 22 MAY 2019 This register of private higher education institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997) (hereafter referred to as the Act). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the Register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The Register is available for inspection at:http://www.dhet.gov.za: Look under Documents/Registers ‐2 ‐ INTRODUCTION The Register provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. -

2020 Integrated Report Stadio Registered As a New Private Higher Education

2020 INTEGRATED REPORT STADIO REGISTERED AS A NEW PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION HIGHLIGHTS “ A NEW VISION IN HIGHER EDUCATION” INSTITUTION STUDENT 26 OCTOBER NUMBERS SUCCESSFUL 2020 INCREASED BUSINESS OFFICIAL 10% TRANSFER INTO BRAND STADIO LAUNCH OF STADIO TO 35 031 ADJUSTED REVENUE * INCREASED EBITDA INCREASED 14% 29% 14% TO R933M TO R253M CORE HEADLINE EARNINGS** CORE HEPS** INCREASED INCREASED 33% 31% TO 14.2 CENTS TO R117M APPOINTMENT * Earnings before interest depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) was adjusted to exclude the fair value adjustment in respect of OF DR VINCENT the CA Connect acquisition. MAPHAI AS ** Core Headline Earnings reflects Headline Earnings adjusted for CHAIRPERSON OF certain items that, in the Board’s view, may distort the financial results from year-to-year, giving management a more consistent THE BOARD reflection of the underlying financial performance of the Group. 2020 ACADEMIC YEAR STUDENT COMPLETED IN DROP-OUT RATES 2020 DECREASED MODULE SUCCESS RATE INCREASED ACCREDITATION OF 2 NEW DOCTORATES IN MANAGEMENT AND POLICING THE GROUP HAS 95 ACCREDITED QUALIFICATIONS AND 35 PIPELINE PROGRAMMES COMMENCED CONSTRUCTION CAMPUSES, 14 OF STADIO CENTURION, SUPPORT OFFICES 2 1ST MEGA- CAMPUS CONTENTS 2 About this Report OVERVIEW 3 Chairperson’s report 01 5 CEO’s report 8 Tribute to our Former Chairperson 9 The Group at a glance 14 Our Market OUR 17 Our Strategy 02 BUSINESS 19 Material Matters 21 Business Model 23 Risks and Opportunities 29 Our Institutions 40 Performance against our Strategic Objectives OUR 43 Value -

Lecturer Profiles

LECTURER PROFILES Servaas de Kock Cephas Forichi Servaas de Kock is the HOD of the Cephas Forichi is a Lecturer at the School of banking department at the School of Investment and Banking. He holds a Master’s Investment and Banking. He has worked of Finance and Investment Management from for Milpark Educatoin since 2011. Wits University. After a short stint as an economist and Prior to joining Milpark Education, Cephas lecturer in his early career, Servaas has worked extensively as an Economist and has gained over 25 years of experience in private, business been widely exposed to the academic field. His research and commercial banking, as well as financial planning interests include alternative investments, capital markets, and insurance, in various senior positions. Servaas corporate finance, and international finance. moved to a full-time academic career in 2009. He is a highly valued facilitator and lecturer, but also a strategic partner in the School. Veronica Hardenberg Dr. Antje Hargarter Veronica Hardenberg is a lecturer at the Dr. Antje Hargarter is the Dean of the School School of Investment and Banking. of Investment and Banking. Antje holds a PhD in Risk Management from NWU as well as an For most of her life, she worked for one of MBA from UCT. She has been with Milpark the four major banks in a mainly operational Education for 10 years, working in academic environment, with specialisation in the management and leadership. fields of Loss Control, Fraud Prevention, and Operational and Compliance Risk. For the last 10 Before coming to South Africa, Antje completed an MSc years at the bank, her role was at a provincial managerial in Management at Johannes-Gutenberg University in level doing operational and compliance risk assessments. -

Accounting Teaching and Learning Journal

0 2 0 2 R E B M E C E D | 1 E M U L O V ACCOUNTING TEACHING AND LEARNING JOURNAL COPYRIGHT © 2020 THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS Copyright in all publications originated by The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (“the Institute”) rests with the Institute. Apart from the extent reasonably necessary for the purpose of research, private study, personal or private use, criticism, review or the reporting of current events, as permitted in terms of the Copyright Act (No.98 of 1978), no portion of this guide may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from an authorised representative of the Institute. CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 Robert Zwane & Karin Jacobsen ADOPTING A PROJECT BASED APPROACH TO EDUCATION 4 Sizwe Nxasana A POST-INDUSTRIAL ERA EDUCATION MODEL 6 Rob Paddock EMOTIONAL SUPPORT 8 Mojalefa Jeff Mosala ENSURING NO PROSPECTIVE CAS(SA) ARE LEFT BEHIND 10 Prof Wiseman Nkuhlu & Sizwe Nxasana HOLISTIC STUDENT SUPPORT FOR OPTIMAL WORKPLACE READINESS: AN EXAMPLE OF THE THUTHUKA PROGRAMME AT UJ 13 Dr Ilse Karsten NURTURING THE CA(SA) PIPELINE DURING A PANDEMIC 24 Ignatius Sehoole PAVING THE WAY FOR THE CTA AT HDIS 27 Roberta Thatcher STELLENBOSCH THUTHUKA PROGRAMME: A CASE STUDY 30 Sybil Smit, Amber de Laan & Gail Fortuin SUPPORT PROVIDED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA TO STUDENTS WHO ARE ON THE ‘FIT’ PROGRAMME 34 Aneesa Carrim & Leana du Plessis TERTIARY EDUCATION GOING ONLINE 38 Gareth Olivier THE ART OF UNLEARNING AND REIMAGINING 41 Graeme Codrington THE CHANGING FACE OF EDUCATION 44 Kerryn Kohl WHY IS MENTORING SO IMPORTANT? 47 Lazarus Kasek Magora EDITORIAL Robert Zwane The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants Karin Jacobsen The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants Looking back to January 2020, a year many of us initially referred to as ‘TwentyPlenty’ because of the multitude of wishes and plans we were making, none of us could have anticipated just how the COVID-19 pandemic would change the way we do everything. -

Prospectus 2019

PROSPECTUS 2019 Milpark is registered with the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) as a private higher education institution (No 2007/HE07/003). Contents 1. A BRIEF HISTORY OF MILPARK EDUCATION 2 SCHOOL OF COMMERCE: PART-TIME STAFF 11 Accreditation and Registration 2 SCHOOL OF FINANCIAL PLANNING AND Vision 3 INSURANCE: FULL-TIME STAFF 11 Mission 3 SCHOOL OF FINANCIAL PLANNING AND Core values 3 INSURANCE: PART-TIME STAFF 12 The student experience 3 SCHOOL OF INVESTMENT AND BANKING: Where to find us 3 FULL-TIME STAFF 12 Melville, Johannesburg SCHOOL OF INVESTMENT AND BANKING: Claremont, Cape Town PART-TIME STAFF 13 Westville, Durban BUSINESS SCHOOL: FULL-TIME STAFF 15 BUSINESS SCHOOL: PART-TIME STAFF 15 2. MILPARK EDUCATION STAFF 4 The Management team 4 ANNEXURE B - STUDENT DISCIPLINARY CODE 17 The Academic team 5 CHAPTER 1: DEFINITIONS 17 Administrative support 5 CHAPTER 2: GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND RULES 17 CHAPTER 3: MISCONDUCT 17 3. MILPARK EDUCATION PROGRAMMES 5 CHAPTER 4: A STUDENT DISCIPLINARY MILPARK EDUCATION SCHOOLS AND PROGRAMMES COMMITTEE (SDC) 18 Business School 5 CHAPTER 5: PROCEDURE IN THE CASE OF A School of Commerce 5 COMPLAINT OF MISCONDUCT 19 School of Investment and Banking 6 CHAPTER 6: GENERAL PROCEDURES AT THE School of Financial Planning and Insurance 6 HEARING OF A CHARGE OF MISCONDUCT 20 Milpark Education College Vocational and 7 CHAPTER 7: SANCTIONS 21 FET Programmes 7 CHAPTER 8: IMPLEMENTATION OF FINDINGS OF Short Programmes and Executive Education 7 THE SDC 21 Short Courses 7 CHAPTER 9: APPEALS 21 Executive Education Programmes 7 CHAPTER 10: REPORTING AND DISCLOSURE OF Corporate Citizenship 7 FINDINGS 22 Business Expertise 8 CHAPTER 11: SAFEKEEPING OF THE RECORD OF Leadership Development 8 PROCEEDINGS 22 Project Management 8 CHAPTER 12: COMMENCEMENT OF THIS CODE 22 Delivery modes 8 CHAPTER 13: OPERATIONAL GUIDELINES 23 Distance learning/contact learning 8 Full-time/part-time study 8 Recognition of prior learning 8 Language Policy 9 4. -

Short Course Programme: Tourism (Intermediate Level) Mode of Delivery: Contact Learning (Melville Campus)

QUALIFICATION: SHORT COURSE PROGRAMME: TOURISM (INTERMEDIATE LEVEL) MODE OF DELIVERY: CONTACT LEARNING (MELVILLE CAMPUS) DESCRIPTION This is a substantive management programme, which enables students to gain an understanding of the main sources of finance, customer services, travel and tourism operations and supervision, global tourism and hospitality and destination analysis. PROGRAMME PURPOSE This Short Course Programme: Tourism (Intermediate level) combines practical career-based elements with a number of essential management disciplines that will be invaluable as the individual’s career progresses. The course therefore provides the practicality needed for the workplace with the theory needed to advance in management roles and in education. PROGRAMME OUTCOMES The aims are to provide a qualification that: • provides students with an understanding of the Tourism and Hospitality Industry and of the key functions within the sector. • provides for an effective academic progression route. • enables students to gain credit towards higher education. • enables students to develop higher-level academic skills that can be applied in a vocational context. © Milpark Education (Pty) Ltd Short Course Programme: Tourism (Intermediate level) factsheet 20a 1 PROGRAMME STRUCTURE Module name and code Assessment method Finance in Tourism and Hospitality FTH Examination Customer Service Management in Tourism and Hospitality CSMTH Examination Global Tourism and Hospitality GTH Assignment Travel and Tourism Operations TTO Assignment Travel and Tourism Supervision TTS Examination Travel Geography TG Assignment Destination Analysis DA Examination ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS • Grade 12 or • CTH level 3 Foundational Programme in Tourism Management. THE CONFEDERATION OF TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY (CTH) The Chartered Institute of Tourism and Hospitality (ITH) is the southern African representative of the Confederation of Tourism and Hospitality (CTH) in the UK. -

Milpark Business School 2021 Prospectus TOMORROW IS BEAUTIFUL Developing Ethical Leaders for the Common Good

Milpark Business School 2021 Prospectus TOMORROW IS BEAUTIFUL Developing ethical leaders for the common good. Contents. 1. Message from the Dean 2 VIEW 9. International Study Tours to Emerging Markets 26 VIEW 2. About Milpark Business School 3 VIEW 10. Applications, Admissions & Registrations 29 VIEW 3. Why Choose Milpark Business School 5 VIEW 4. Milpark Business School Executive Faculty 6 VIEW 5. Accreditations, Affiliations & Partnerships 8 VIEW “What counts in life is not the 6. The United Nations: Seventeen Sustainable mere fact that we have lived. Development Goals by 2030 10 VIEW It is what difference we have made to the lives of others that will determine the significance 7. Programmes 13 VIEW of the life we lead.” - Nelson Mandela Nobel Peace Prize Winner 1993 8. Executive Education 20 VIEW Message from About Milpark 1the Dean. Business School. 2 Tomorrow is beautiful. The old truths suggest that to lead, leaders must have foresight. They must lead by example; they must motivate and inspire on a moral basis, through aspiration as well as recognition and reward. It is precisely this calm, considered, and ethical leadership, required to lead and inspire large numbers of people that seems in short supply today. This has been made even more challenging considering the Covid-19 pandemic. Cognisant of the drivers of change, the megatrends, and the global pandemic impacting on society, we are aware of the responsibility and trust that we as a business school of the next generation of leaders bear. Hence, ethical and sustainable business practices is at the heart of our teaching and research philosophy. -

Study with Milpark College to Become a HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT and PRACTICES GENERALIST!

CAPE TOWN CAMPUS: Tel: (021) 673‐9100 Fax: (021) 673‐9111 2nd Floor, Sunclare Building, Corner Dreyer & Protea Roads, Claremont JOHANNESBURG CAMPUS: Tel: (011) 718‐4000 Fax: (011) 718‐4001 Corner Main Road East and Landau Terrace, Melville Extension 2 DURBAN CAMPUS: Tel: (031) 266‐0444 Fax: (031) 266‐0466 Westville Office Park, 54 Norfolk Terrace, Westville Visit our website: http://www.milpark.ac.za Email us: [email protected] Study with Milpark College to become a HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT AND PRACTICES GENERALIST! Your Qualification: Diploma in Human Resources Management and Practices, NQF Level 5, SAQA ID 61592 Your Certifying Body: SA Board for People Practices (SABPP) Your SABPP Designation: Human Resources Technician (HRT) Your Career Options: Human Resource Practitioner, Human Resource Senior Practitioner, Human Resource Manager, Human Resource Junior Generalist Mode of Delivery: Online Learning. IS THIS THE RIGHT PROGRAMME FOR YOU? This programme is right for you if you have one or more of the training or career needs below: I would like to make human resources management and practices my career, and would like to work in the human resources department, or related department of a company. I would like to open my own human resource consulting practice one day. I am running a small business and need to know more about the human resources and practices function. MORE ABOUT SA BOARD OF PEOPLE PRACTICES (SABPP) Although Milpark is offering tuition towards the National Diploma in Human Resources Management and Practices, the SA Board for People Practices (SABPP) certifies the qualification in terms of set requirements of the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA).